The Information features a fascinating article on how, perhaps for the first time in quite some time, Amazon’s primacy as the go-to place for e-commerce is being challenged by the likes of Temu and Shein.

If you’ve never heard of Temu, you either didn’t watch the Superbowl (where they ran three ads) or you live in a cave. Not that there’s anything wrong with living in a cave… or not watching the Superbowl, for that matter.

Here’s an example of one of the most popular products on Temu’s marketplace (the #2 best seller): a tortilla blanket going for $6.28.

I know, you’re probably thinking, “I’m sure Amazon carries such a staple too.”

And indeed:

You can get one from Amazon with free next-day shipping (after all, if you’re set on a tortilla blanket, you absolutely MUST get it by the next day), but in this case, you must pay the unrealistic price of $11.99.

However, I’m sure this is not Amazon’s second most popular product. In fact, it’s not even a best seller in their Home & Kitchen category.

Their best seller is, of course, the Stanley Tumbler. If you’re not familiar with that story, you absolutely live in a cave, so you should stop reading and focus on becoming acclimated to society once again (this newsletter can wait).

Back to the news article…

Based on the Information, Amazon is facing a well-funded challenger in Temu for the first time. As the graph below shows, the firm surpassed Target and is growing faster than Amazon or Walmart, and in a relatively short amount of time.

Before I continue with the article and the actions Amazon is trying to take (and their analysis), let’s put this new development in a historical context.

Amazon: The Everything Store

For many years, Amazon primarily competed with offline retailers, such as Walmart, aiming to become the biggest U.S. retailer by focusing on variety and cost and becoming “The Everything Store.”

The firm not only became “The Everything Store,” but moved on to also become the “Everything Prime Store,” meaning not only everything, but everything tomorrow, the next day, in the next 15 or even 11 minutes.

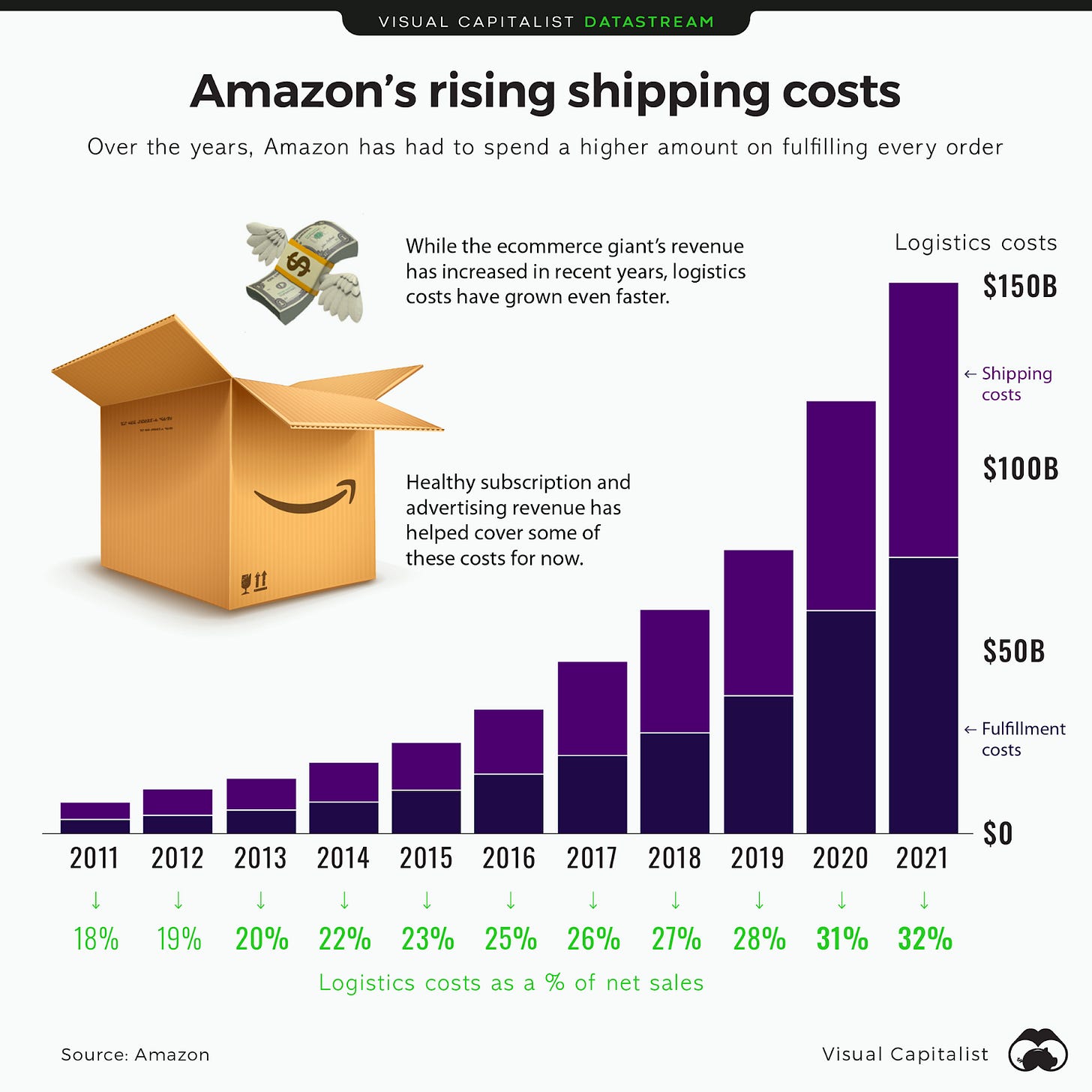

As we’ve explained before, to do so, Amazon had to build an impressive logistical network, which, while encouraging more sellers to sell on Amazon, also had significant cost implications:

Temu is also an “Everything Store,” but mostly an “Everything Really Cheap Store.”

The issue: Amazon cannot reverse course. It can’t stop betting on convenience, but it has to mount a response at Temu.

Amazon Betting on Curation

Now, this is a familiar dynamic: In any competitive setting, firms like Amazon are constantly on their toes, adapting to the shifting sands of competition and consumer preferences. Andy Grove famously wrote “Only the Paranoid Survive.”

So what is Amazon planning to do?

The strategy revolves around enhancing consumer choice and seller competitiveness…the introduction of a second BuyBox.

You may ask: Why is this the only way Amazon can “retaliate”?

According to the article, the discussions within Amazon’s team highlight the delicate balance the company must maintain.

On the one hand, Amazon benefits significantly from its relationship with Chinese merchants, who are also selling on Temu, and provide a vast selection of low-priced goods while contributing to Amazon’s revenue through advertisement and logistics fees.

On the other hand, there’s a looming risk that mimicking Temu’s model could inundate Amazon with low-quality goods, compromising its reputation for quality and speedy delivery.

Recognizing the threat posed by Temu’s aggressive pricing and direct-to-consumer shipping model, Doug Herrington (head of Amazon’s e-commerce business) and his team sought ways to counteract these challenges while preserving Amazon’s quality and timely delivery reputation. This contemplation led to the idea of a second BuyBox highlighting lower prices, diverging from Amazon’s traditional emphasis on delivery speed.

This proposed BuyBox represents a shift in Amazon’s strategy.

Traditionally, Amazon’s BuyBox— the coveted space on a product listing that features the “Buy Now” and “Add to Cart” buttons—has been awarded based on a mix of factors, with a heavy bias toward sellers who offer the fastest delivery times, often through Amazon’s Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) service.

If you’ve never heard the term, this is what we’re talking about:

However, introducing a second BuyBox would prioritize the lowest price, potentially leveling the playing field for sellers who manage their shipping, including those shipping directly from China without using FBA.

According to the article, this move is with precedent; Amazon has implemented a similar feature in the EU as part of an antitrust commitment. The discussion around a second BuyBox in the U.S. shows Amazon’s willingness to adapt its platform to foster competition and cater to consumer demand for lower prices, even if it means de-emphasizing its Prime delivery speed.

The implications of this strategy are significant. It could enhance the visibility of more competitively priced products, encouraging sellers to lower their prices to win the BuyBox, thereby making Amazon’s offerings even more competitive against Temu and other low-cost rivals. This strategy aligns with Amazon’s broader efforts to adjust its fulfillment and commission structures to benefit sellers and consumers alike, as evidenced by the discussions around lowering Amazon’s take on items sold through the Merchant Fulfilled Network (MFN).

The BuyBox

But I know… you are probably asking yourself: Amazon is facing the first real emerging competitive threat, and the only thing it can do is … offer a second BuyBox?

It’s like the 49ers choosing to start overtime when playing against the best prime-time quarterback of this decade (we’ve already established that if you didn’t watch the Superbowl, you shouldn’t be reading this).

So, let’s understand the impact of the BuyBox.

This tool is designed to simplify the shopping experience by presenting a single listing as the default option for consumers, an approach that has significantly impacted marketplace dynamics.

The paper “Algorithmic Assortment Curation: An Empirical Study of Buybox in Online Marketplaces” by Santiago Gallino, Nil Karacaoglu, and Antonio Moreno, studies the BuyBox’s impact on different marketplace stakeholders.

The analysis, conducted by examining BuyBox’s staggered introduction across a major product category, reveals that its implementation facilitates smoother transactions for buyers and sellers, and leads to a noticeable increase in marketplace orders.

For consumers, the BuyBox reduces the effort required to sift through multiple listings, a notably pronounced benefit on mobile devices where search frictions are inherently higher. This is expected.

As is evident from the graph below, since the introduction of the BuyBox, both the conversion rate and the overall number of orders have increased.

I think the more interesting result is that sellers experience reduced barriers to entry, as indicated by an increase in the number of sellers per product following the BuyBox’s introduction.

The study further highlights that competition for the BuyBox spot results in lower prices and higher quality for consumers, which aligns with Amazon’s strategy to offer competitively priced products without compromising quality or delivery speed.

However, the analysis also points out an unintended consequence of the BuyBox’s introduction: a more concentrated marketplace.

To be clear: Amazon already has a BuyBox, so everything in this research paper is already true for Amazon even before the introduction of the second BuyBox. But a second BuyBox focusing on lower cost can allow the firm to keep the right balance between ensuring the message of “convinience” while also being “inexpensive.”

Is Amazon Hurting its Own Marketplace?

The BuyBox is a form of curation once you’re already on a product page. But curation also happens when we search for a product before we click on the specific product. And there, I would argue, Amazon is taking actions that potentially hurt its marketplace viability.

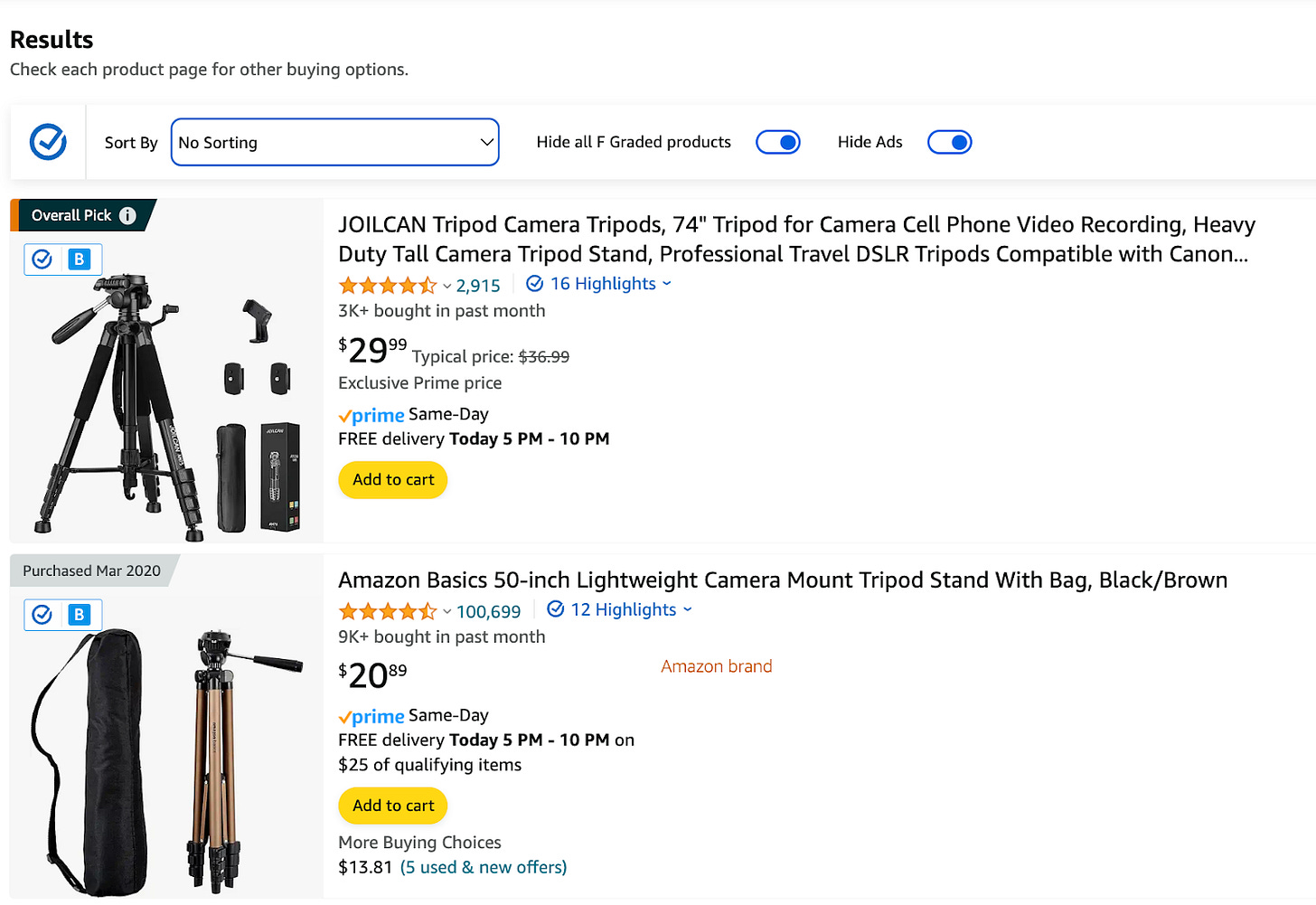

As we can see in the screenshot below when searching for “Camera Tripod,” Amazon features an “Amazon Basics” product in the second slot.

Both number 1 and number 2 slots have 4.5 points, both are Prime products. In fact, the Amazon-branded one is cheaper.

Yet, it begs the question: Is Amazon self-preferencing their products?

In their paper “Self-Preferencing at Amazon: Evidence from Search Rankings,” Chiara Farronato (who just gave a talk at Wharton), Andrey Fradkin, and Alexander MacKay study this question, and their answer is: Yes!

The paper provides evidence that Amazon engages in self-preferencing its products on its marketplace. Specifically, the researchers find that Amazon-branded products are ranked higher in consumer search results than other sellers’ observably similar products. This is demonstrated through collecting new micro-level consumer search data, which reveals how Amazon brands are ranked higher in search results, holding other observable factors constant. This behavior aligns with the concerns of regulators and critics regarding digital platforms’ potential to favor their products over those of third-party sellers.

In a subsequent work, which Chiara presented this week, they used an alternative test: if two products are ranked the same, if self-preferencing happens, we should see a lower purchase rate of the Amazon-branded product. Using this test, there’s no evidence of self-preferencing.

So the immediate next question is, “Does this actually hurt the marketplace?”

The paper suggests that Amazon’s practice of self-preferencing may have mixed effects:

Competition and Innovation: Favoring Amazon-branded products in search results could potentially discourage product innovation by other firms and prompt some competitors to abandon the market altogether. This indicates a negative impact on competition and innovation within the marketplace.

Consumer Choice and Welfare: While introducing and promoting new Amazon products can increase variety and potentially reduce prices, preferential treatment can make it difficult for consumers to find their preferred options or even be aware of them. This could harm consumers by limiting their choices to a less diverse product range and possibly affect the overall quality of available products.

In her talk, Chiara also presented new results showing that removing the Amazon Basics products doesn’t actually impact consumer behavior. Customers still have several options to choose from.

But this brings me to the most important issue.

Market Dynamics: Self-preference might lead to a marketplace where Amazon-branded products dominate certain categories, potentially reducing the diversity of offerings, and affecting the overall health of the marketplace ecosystem. The actual harm, of course, depends on the extent to which consumer choice is limited and whether consumers are dissatisfied with the offerings.

But apart from the points mentioned above, the paper also notes the need for further research to fully understand the effects of Amazon’s ranking policies and the presence of Amazon brands on consumer welfare. This suggests that while there are indications of potential harm, the full impact on the marketplace requires a more comprehensive analysis.

But the reality is clear: if the goal is to compete with another marketplace (like Temu), implementing strategies that may alienate sellers seems like a long-term mistake.

Personally, I like the Amazon Basics products that I’ve bought. They were fairly priced and functioned well, but they also weren’t always great. For example, I bought a few of these tripods, but when I needed a good tripod for my Zoom setting, I bought one from Oben, and I bought it on B&H, not Amazon. So while Amazon is “The Everything Store,” when you need a reliable opinion for a reliable product, it’s just not “the go-to place” anymore.

Final Words

In summary, Amazon’s strategic introduction of a second BuyBox and the subsequent analysis of the BuyBox tool illustrate the company’s multifaceted approach to maintaining its competitive edge. Through algorithmic curation and strategic adjustments, Amazon seeks to balance consumer demand for lower prices with the need for a high-quality shopping experience, reflecting its ongoing commitment to growth.

In the epic saga of online shopping, where Team Amazon and Team Temu battle for the crown with their arsenal of ads and tortilla blankets, the real twist is discovering that the ultimate comfort doesn’t come from speedy delivery or jaw-dropping discounts. Instead, it’s knowing that, amidst the chaos of e-commerce wars, you can still wrap yourself in the simplicity of a $6.28 blanket and pretend you’re a giant burrito, unbothered by the world’s marketplace melee.

I wonder what and when would be a margin pressure due to low priced items on Amazon's retail business due to this decision? Or would the BuyBox simply is a real estate for Amazon to put its own Amazon Basics products more prominently?

Professor Allon,

I really liked your take on how Amazon is adapting amidst increasing competition. I wonder if (or maybe how much) this "second BuyBox" will actually impact customers' decisions. It doesn't surprise me that Amazon self-preferences, but the quality of a company's own products definitely contributes to the company's validity and consumers' trust (e.g. Costco does an excellent job with their Kirkland Signature). Great insights as always.