Bending it Like Beckham: Amazon’s Attempt at Groceries and the Curve of Scalability

A flurry of news about Amazon just came in. From better-than-expected results on their retail to rethinking their grocery business, Amazon continues to evolve and adapt. Sometimes successfully, sometimes less so.

Good News: Better Than Expected Results

In a recent earning call, Andy Jassy, the CEO of Amazon, emphasized the improvements in the North American e-commerce business, from handling returns differently to regionalizing fulfillment, the firm is swinging back to profitability:

“The company has been reining in spending in its e-commerce arm after overbuilding during the pandemic, including by changing how it handles returns and [regionalizing its fulfillment network to reduce the odds that a customer’s overnight order of kitty litter winds up on a cross-country flight. Those changes helped its North America division swing from a $627 million loss during the second quarter of 2022 to a $3.2 billion profit in the same period this year. Amazon said it expects more improvements in the coming quarters.”

Amazon Web Services (AWS) continues to be a significant source of profit, but interestingly, the firm’s e-commerce in North America shows consistent improvement. Over the past six quarters, the operating margin has risen to 3.9%. Though modest compared to AWS’s current 24.2%, e-commerce generated almost four times AWS’s revenue last quarter. Even small increases in profitability can make a substantial difference for Amazon. The market’s response was a 9% increase in Amazon’s shares in after-hours trading.

Not So Good News: The Grocery Business

However, not all is sunny in Amazonland, as Bloomberg reported that:

“Amazon.com Inc. is launching the biggest overhaul of its grocery business since it acquired Whole Foods Market six years ago - revamping stores, testing new highly automated warehouses and, for the first time, offering fresh-food delivery to customers who aren’t Prime subscribers. In a move likely to play well with shoppers, the company also plans to merge its various e-commerce supermarket offerings from Whole Foods, Amazon Fresh, Amazon.com - into one online cart.”

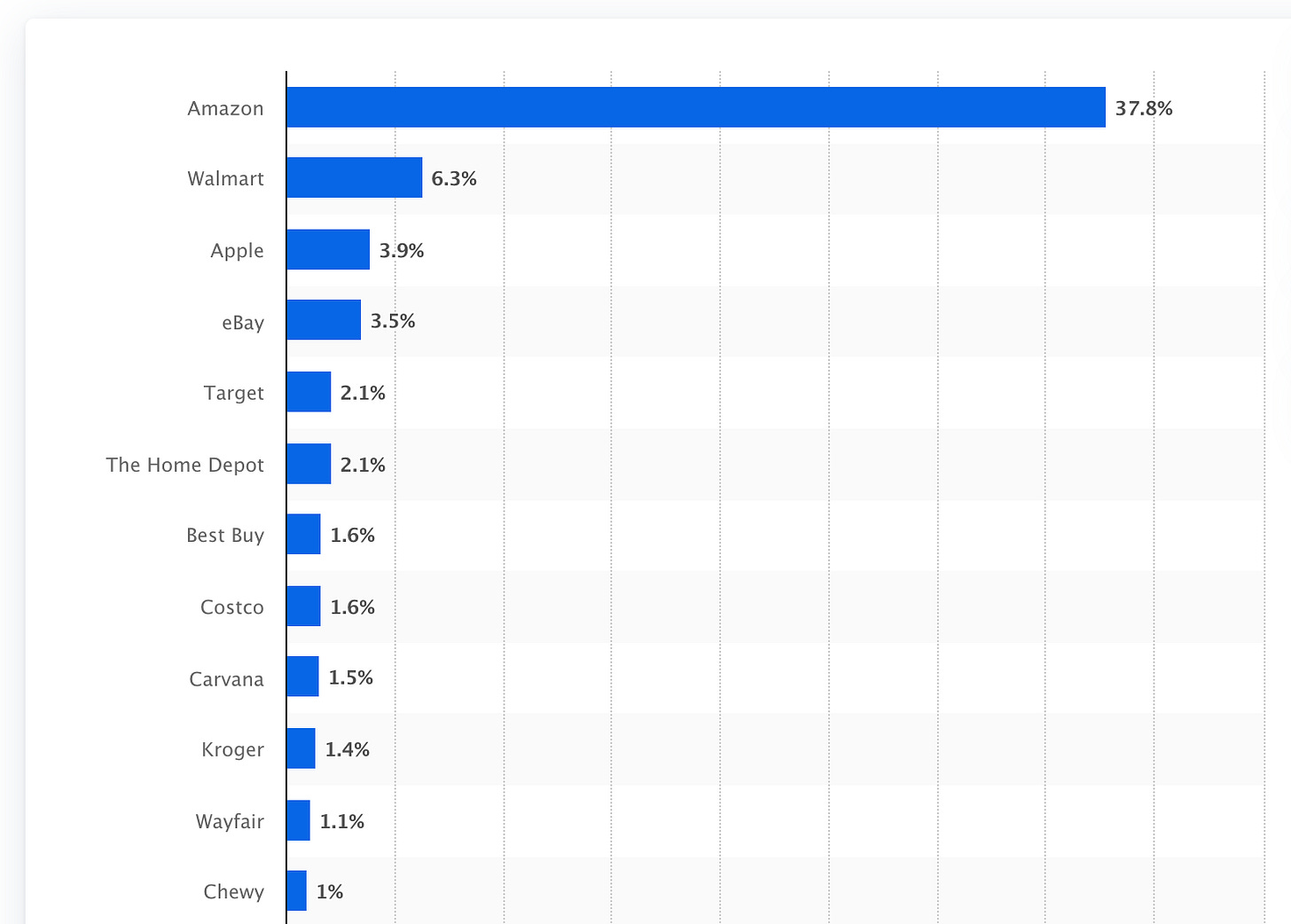

The reason? While Amazon is the largest online retailer by far,

and the second largest in general…

When it comes to the grocery market, it falls short:

In a concerted effort to seize a more substantial portion of the U.S. grocery market, Amazon announced its plan to make significant changes in the coming weeks and months.

Under the leadership of Tony Hoggett, a former Tesco Plc executive with extensive brick-and-mortar experience, Amazon is shifting its focus. According to Hoggett, the company aims to transform itself from a niche grocer specializing in organics and home delivery of essential household items into a go-to destination for budget-conscious shoppers looking to consolidate their shopping trips. ‘We’re serious about grocery,’ Hoggett asserted, outlining the company’s long-term plan to build ‘a really strong grocery relationship with customers.’ The elevation of more traditional retail executives within the organization underscores Amazon's renewed commitment to becoming a major player in the grocery sector.

Bloomberg notes that:

“Amazon customers have long expressed frustration that they need to check out from three separate web pages to get everything on their shopping lists. Consumers who want king salmon fillets (sold by Whole Foods), a pack of shredded lettuce (sold by Amazon Fresh) and a box of Cheerios (sold, with other shelf-stable products, by Amazon.com) sometimes found themselves making three different orders—ferried to their homes in three separate deliveries. The company is looking to simplify the process this year or next by stocking more Whole Foods products in Amazon warehouses and creating one cart.”

As part of this process, Amazon is revitalizing its Fresh stores, expanding inventory by approximately 1,500 items, and enhancing the overall atmosphere with bright colors. Within the stores, there’s a shift toward traditional retail aesthetics rather than technological innovations.

The new design emphasizes a brighter and more inviting experience, a departure from the previous Fresh store concept. However, technological elements like Amazon’s Dash carts, now equipped with basic barcode scanners, remain. These carts provide a running tally of items and are backed up by a scale. Additionally, the redesigned Fresh stores will incorporate self-checkout lanes, though the Just Walk Out cashier-less technology, first introduced in Amazon’s Go stores, will still be an option for shoppers.

This is a significant shift in Amazon’s approach to its grocery business, as Whole Foods previously operated rather independently from Amazon’s other grocery endeavors. This started to change under the leadership of Hoggett, who, according to Bloomberg, is currently working from Whole Foods’ headquarters in Austin. Whole Foods executives are now in charge of all of Amazon’s grocery real estate and branding, and an Amazon veteran heads Whole Foods’ technology teams.

According to certain analysts, Amazon needs significantly more stores to become a leading player in this market so the company plans to open 50 new Whole Foods locations and aims to develop 100 stores within the next few years. Amazon’s Fresh, currently operating 44 stores, will likely also expand if in-store adjustments prove successful. The company may also grow by acquiring stores that are expected to be offloaded in the upcoming Kroger and Albertsons merger.

So, while the news is good for retail, the grocery business is met with challenges and big ambitions. To understand both, we must first understand Amazon and economies of scale.

Amazon and Scale Economies

At its core, Amazon is all about scalability and economies of scale.

But what do I mean by scalability? It’s a word that gets thrown around a lot, like a hot potato in the world of business, so let’s make it more precise.

In its most fundamental sense, scalability happens when revenue growth outpaces cost growth. If we think of it as running a race, scalability is when revenues sprint faster than costs. So for every dollar you spend, you’re aiming to get more in return - that’s the essence of scalability. Simply matching dollar for dollar doesn’t truly scale in the long term, as any shock (say, a pandemic, or a recision) or increased competition (from a new entrant to a current player) can cause your revenues to tumble down a hill while your costs stubbornly remain put.

Now, envision a graph. On the x-axis, you’ve got your ‘number of units’ (this could be anything - packages, digital downloads, giant teddy bears, whatever). Your costs and revenues are running up the y-axis, and everything boils down to how these two variables change as you grow:

Amazon’s prowess is building business infrastructure that scales. Its inventory management and supply chain capabilities primarily spring from its ability to pool and centralize resources. This approach allows it to maintain high service levels with limited inventory, shipping to customers wherever they are.

In this context, Amazon is an intriguing company to study. They invest more as they grow, stocking up on more inventory, retail space, or warehouse space. Yet they’ve been good at bending the cost curve downwards, making the most of their scalable operations (i.e., their economies of scale).

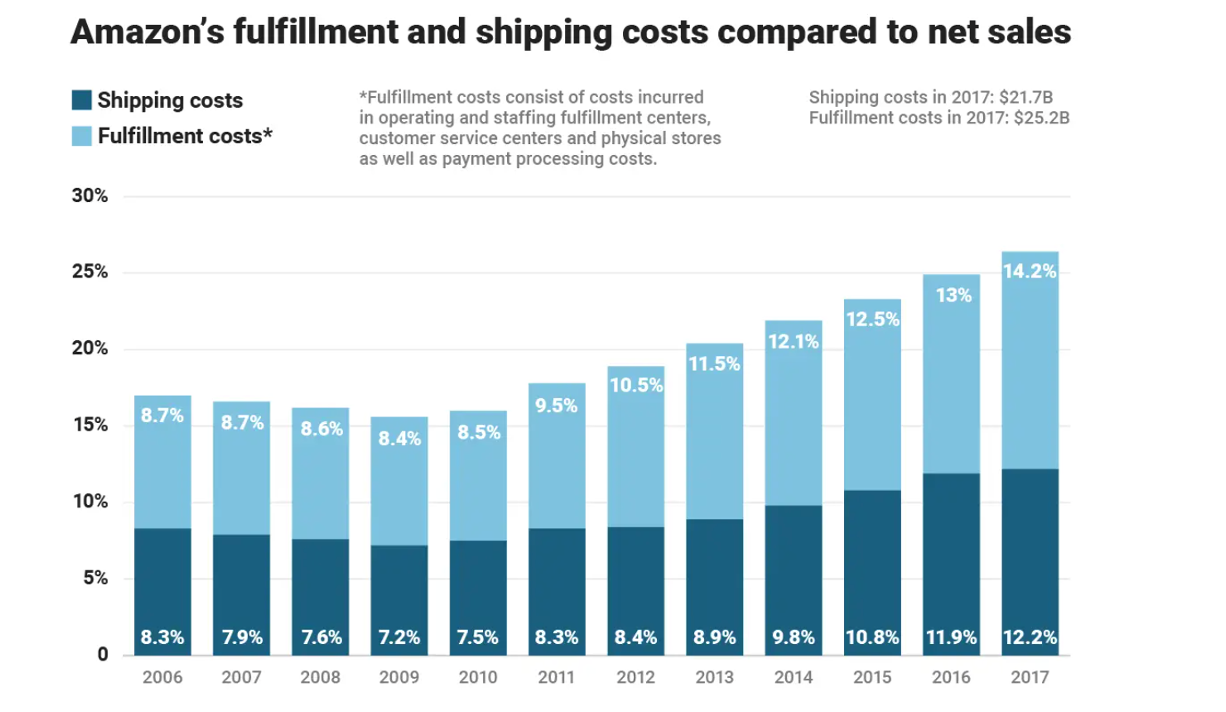

However, in 2010 things started to turn. Amazon began investing heavily in fulfillment centers and hiring more people, but the cost curve seemed to be bending the wrong way. Rather than achieving economies of scale, they’ve been facing diseconomies of scale.

The following graphs show the last few years where the company enjoyed economies of scale (until 2009, the cost of shipping and fulfillment as a % of revenues decreased), followed by a sharp turn in 2010:

And as we can see, this trend continues well into 2022:

And this trend continues now:

“Net sales for Amazon’s online stores in the second quarter reached about $53 billion, a 4% rise year over year, the company said Thursday. Sales at the retailer’s physical stores also rose 6% to $5.02 billion.Third-party marketplace seller services rose 18% to $32.3 billion; …During the same time, fulfillment costs rose 22% to $932 million compared to a year ago.”

Here’s where the numbers tell a tale: Amazon’s spending on shipping and fulfillment now makes up 35% of its overall operating expenses, up from 28% in 2019. That translates to roughly $40 billion last quarter, against revenue from physical and digital product sales of around $56 billion. The excess space and overhiring added another hefty sum to the costs.

Understanding Amazon’s Issues: Analyzing the Graph

What’s caused this shift?

The last mile.

Amazon has invested in convenience and speed, harder attributes to replicate, thereby shifting its scale strategy.

Amazon’s expansions have been occurring at a critical juncture as the company contends with rivals in the retail market. Through ultrafast delivery, the tech giant aims to leverage its extensive logistics network to challenge competitors like Walmart Inc. and Instacart, both of whom offer quick shipping options. Walmart, in particular, has capitalized on its vast store presence to facilitate rapid online order fulfillment:

“‘Sometimes I hear people make the argument that Amazon is chasing faster speed, while driving its costs higher and where it doesn’t matter much to customers. This argument is incorrect,’ Jassy said during the earnings call. ‘First, customers care a lot about faster delivery. We have a lot of data that shows when we make faster delivery promises on a detail page, customers purchase more often. Not just a little higher, meaningfully higher. It’s also true that when customers know they can get their items really quickly, it changes their consideration of using us for future purchases too.’”

So one thing is that customers want speed.

Another is that Amazon believes that is where its moat is.

To have an order ready for “same day delivery,” Amazon targets having the order ready for delivery in 11 minutes. To do that, they first have to spread out their inventory as close to consumers as possible —think of it like scattering pieces of a puzzle across the board— and second, they need employees on standby, ready to pick-and-pack the order. Their automation has to be super-fast and capable of lightning-quick selection methods.

But here’s the twist! There’s no pooling. No grouping together of inventory or shipments or anything related to that.

This Amazon network is far more than a bunch of warehouses and speedy conveyor belts. It’s about strategic placement of resources, rapid response systems, and skilled manpower, all intricately linked together. It’s not just an operation; it’s a massive investment in logistical engineering that would make even the most audacious competitors think twice. You see, over the past dozen or so years, Amazon has been constructing this capability - first, it was next-day, then same-day, and soon it might just be “within the hour.”

Now, you may wonder, do we really need our online orders in a blink of an eye? I would say we do. We don’t need it for every single item.,but for certain things, such as grocery and convenience items, the answer is yes. And if Amazon can do it at no additional cost, then why not?

This is where Amazon believes the future lies and also where they believe they can create a solid barrier, a moat, if you will, to keep the competition at bay.

And the charm of this physical structure is that it’s a more enduring and tangible moat than a virtual one. You see, a virtual moat —say an AI model or a clever algorithm— can be copied or reverse-engineered given enough time and talent. But a vast, sprawling network of warehouses, advanced automation systems, and a workforce that's been trained to perfection… Now, that’s a different story. It’s like the difference between having a map of a treasure island and actually owning the island! This is Amazon’s ace up their sleeve —a physical infrastructure that’s not just about size, but also about speed, agility, and adaptability.

So after many years of diseconomies of scale, this investment starts to payoff and transition from pure growth to profitability, all that happening through a long process of optimization of this network.

So, why does Amazon need to rethink its grocery rather than just continue and optimize?

Why are Groceries Difficult (for Amazon)?

Amazon’s ‘grocery journey’ has been marked by ambitious endeavors and challenges. In 2007, the company launched AmazonFresh, with the intention of disrupting traditional grocery shopping. Despite initial promise, this service has failed to make a substantial impact. A significant move came in 2017 when Amazon acquired Whole Foods, signaling its serious intention to penetrate the grocery industry. This acquisition aimed to combine Amazon’s technological might with Whole Foods’ well-established physical stores. However, integration challenges and high prices have hindered its success. Additionally, Amazon introduced the innovative concept of cashier-less stores with Amazon Go, offering a seamless shopping experience, but scaling this model has proven to be both complex and costly.

Overall, Amazon’s venture into the grocery sector has proven to be an uphill battle since grocery retailing requires a different approach, which involves physical shopping experience and curation—two areas where Amazon doesn’t excel.

However, the ongoing efforts demonstrate Amazon’s tolerance for experimentation and a move toward reducing friction for non-Amazon customers through services like Amazon Go.

But why are these promising ventures met with such difficulty?

Consumer Habits: Grocery shopping is a highly personal experience, and consumers have well-established preferences and routines. Shifting those habits requires more than technological innovation.

Logistical Complexity: Unlike other retail items, groceries require specialized handling and storage. Amazon’s established logistics network wasn’t designed to handle perishable goods, thus leading to inefficiencies.

Market Competition: Traditional grocery stores and new entrants like Walmart’s online grocery service have offered stiff competition. Amazon’s typical playbook of aggressive pricing and convenience hasn’t been enough to overcome the competition.

Misaligned Business Model: Amazon’s success in other retail sectors was not easily transferable to groceries, leading to smaller economies of scale.

The grocery sector is tricky, even in a physical store setting, balancing inventory, managing fresh products, and catering to diverse customer preferences, is not exactly a walk in the park when it comes to scalability.

Historically, Amazon’s strength lies in its ability to offer a vast, diverse catalog of products - the ‘long tail.’ But, when it comes to groceries, we repeatedly buy the same essentials rather than searching for unique or obscure items. So, Amazon’s long-tail approach doesn’t quite translate to this landscape.

This presents a complex problem for Amazon as scaling grocery shopping isn’t as straightforward as expanding warehouses or enhancing supply chains. It’s a different game, with different rules.

Persistence: Doubling Down

Despite these “failures,” Amazon continues to invest in the grocery market, and the question is why?

Strategic Importance: The sector’s significant size and recurring nature make it a crucial market to conquer. The entire U.S. retail sector is estimated at $7.1T, and Grocery is $1.5T of that. Success here could amplify Amazon’s overall retail dominance while giving up can create an opening to Walmart, but also to the likes of DoorDash and Uber.

Data Utilization: Amazon’s ability to gather and utilize consumer data could eventually give it an edge in personalizing the grocery shopping experience. This is an area where Amazon should have some edge over the competition.

Long-term Vision: Amazon’s history shows a willingness to endure short-term setbacks for long-term gains. The company may see the current failures as learning experiences, part of a larger strategy to understand and eventually master the market.

Synergy with Other Services: Integrating grocery services with existing Amazon products, such as Prime and Echo, may provide a unique value proposition that competitors can’t match. This is also exactly where the dense network of ultra-fast delivery can be meaningful.

In other words, the moat Amazon is building for same-day delivery may just be the first step in seizing the grocery market, if not the only step. In fact, growing the grocery business, given its scale and density, can be the key to bending the curve.

Amazon’s grocery journey is like a gripping novel filled with plot twists, challenges, and the pursuit of what seems as an elusive goal. From its humble beginnings to strategic acquisitions, the journey has been anything but smooth. But like a tenacious protagonist, Amazon keeps pushing forward, learning from its mistakes and making new strides.

But as we see, it’s not only groceries. It’s about groceries and same-day networks.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to whether or not Amazon can bend that curve.