Challenges and Trends in Shifting Global Supply Chains: When De-risking Becomes Re-risking

In recent years, numerous industries have been restructuring their supply chains away from China.

Last week, Bloomberg had an interesting article on the fact that some firms are now moving back:

“From Adidas AG to Nike Inc., apparel and footwear makers have been shifting their supply chains out of China, pushed by geopolitical tensions and pulled by lower manufacturing costs.

But amid mounting global economic uncertainties and weakening consumer demand, many are discovering that finding alternative production hubs comes with its own challenges. Some are even upping stumps and moving back to the mainland.”

One must be careful of course when reading such an article.

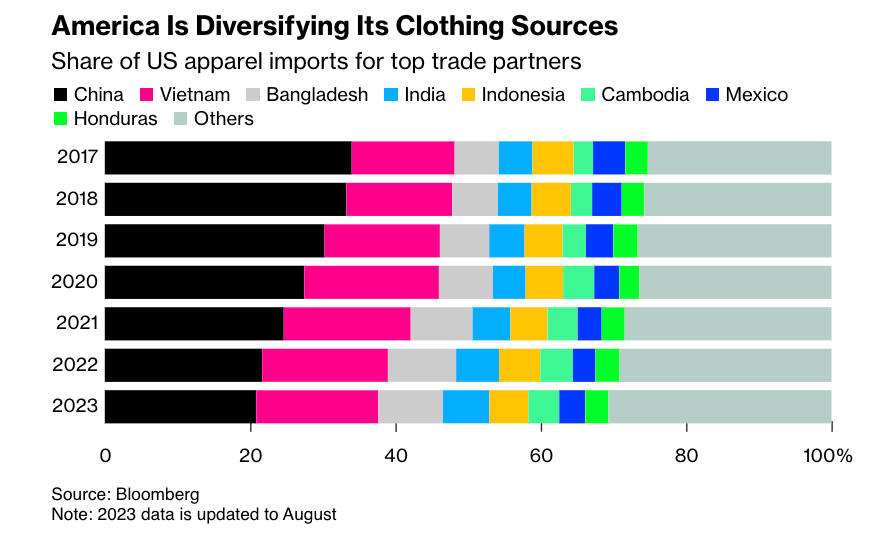

Based on the data, the trend is to move production from China to neighboring countries:

The plot twist, however, is that in many of these countries, the investors are Chinese manufacturers…

…and the raw materials and intermediate goods are still sourced from China:

So if a big part of moving away from China was to de-risk supply chains against geopolitical risks, is the goal being achieved?

Let’s delve deeper.

Main Issues Faced by Firms

Why is it so hard to relocate?

Geopolitical and Economic Pressures: Geopolitical tensions between China and the West have prompted many brands to seek alternative production hubs. This shift, however, is fraught with difficulties as companies face significant challenges in replicating the mature and established ecosystem found in China, which has been built over decades. In the Bloomberg article, Laura Magill, the global head of sustainability at Bata Group, highlights that no other region offers the same combination of competitive pricing, stable quality, and mass production capabilities.

Economic Uncertainties and Consumer Demand: Global economic uncertainties and weakening consumer demand further complicate the relocation process. In the same article, Lin Feng, an apparel factory owner, discusses the difficulties of moving production to Vietnam: Despite lower labor costs, weak demand led to minimal orders, prompting him to return operations to China.

Supply Chain Dependencies: As mentioned above, even as companies relocate, they depend heavily on Chinese materials. Vietnam, for instance, relies on Chinese supplies for components such as buttons, thread, and packaging, with only 30-40% of materials being produced locally. This dependency raises questions about the true effectiveness of shifting supply chains if key inputs still originate from China. This scenario is also mirrored in other industries, such as electronics, where Chinese components remain critical.

So why not go back to China?

Trade-offs and Trends

As I usually say: There are no optimal solutions. Only trade-offs.

Cost vs. Quality and Efficiency: While the lower labor costs in countries like Vietnam and Cambodia are attractive, workers’ efficiency and skill levels are inferior to those found in China. Kee, a manager of a Guangdong-based apparel factory, notes in the article that although labor costs in China are higher, the output rates and worker skills are better, making expansion in Southeast Asia less rational amid business slowdowns. Similar dynamics are observed in electronics manufacturing.

Environmental and Political Constraints: Setting up new factories involves substantial costs both financial and environmental.Certain governments impose strict regulations, such that may discourage new setups to avoid environmental degradation. In the electronics sector specifically, stringent environmental regulations impact companies’ decisions regarding where to set up new facilities.

Regional Shifts and New Beneficiaries: Countries like India and Mexico have benefited from the diversification away from China. Fast Retailing Co.’s Uniqlo and Apple Inc. have increased production in India, while Chinese manufacturers have established plants in Mexico to leverage the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement. However, whether these nations can match China’s vast manufacturing ecosystem remains to be seen. This trend is also present in various industries, including automotive and consumer goods.

Increased Complexity and Costs: As supply chains lengthen, complexity and costs increase since more steps in the production process often lead to higher prices. This complexity can negate some of the intended benefits of diversifying supply chains, making it harder to apply economic pressure on China during future crises. For example, in the semiconductor industry, lengthened supply chains can lead to increased costs and logistical challenges, impacting overall efficiency.

Shifting global supply chains from China to other regions involves navigating all of these challenges and trade-offs.

While geopolitical tensions and economic pressures are what drive these changes, the established manufacturing ecosystem in China remains unparalleled at this point. Companies must weigh the benefits of lower labor costs and diversified production against the challenges of maintaining quality, efficiency, and stability in new markets. As global supply chains continue to evolve, the balance between cost, quality, and resilience will be critical in shaping the future of various industries, from electronics to apparel.

The Looming ‘Great Reallocation’

When reading these articles, we must question whether the evidence provided is anecdotal. So, let’s look at the relevant research.

A noteworthy post-COVID trend is the interest that economists have developed in supply chains—NBER held a whole workshop on the topic.

One of the most interesting papers is “Global Supply Chains: The Looming ‘Great Reallocation.’” The paper addresses the stress imposed on global supply chains due to U.S.-China trade tensions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other geopolitical shocks. It examines the U.S. participation shifts in global value chains (GVCs) over the last four decades, focusing on the most recent five-year period between 2017-2022.

The paper’s main research question considers how recent events and policies have influenced the reallocation of global supply chains, particularly concerning U.S. sourcing from China, and alternative locations.

The authors use a comprehensive analysis of product-level trade statistics from the UN Comtrade, multinational activity data, earnings calls, and other data from the U.S. manufacturing sector. They document changes in the pattern of U.S. import sourcing and explore the implications of these shifts.

The main results are quite interesting.

First, they show that there is a noticeable shift away from direct U.S. sourcing from China, with alternative low-wage locations like Vietnam and nearshoring options such as Mexico, gaining a larger share of imports.

Furthermore, they show that the U.S. import profile has become more upstream, indicating some reshoring of production stages.

However, despite the reallocation, policies may not significantly reduce U.S. dependence on China-linked supply chains, as China increases its trade and FDI in Vietnam and Mexico.

The paper also documents rising prices of imports from Vietnam and Mexico, suggesting higher production costs.

The implications are clear: The policy-driven reallocation away from China may not achieve the intended goal of reducing dependence on China.

In fact, the two worrisome trends are:

Increased Supply Chain Length: The lengthening of supply chains, particularly between China and the U.S., indicates that firms are not fully decoupling from China. Instead, they are incorporating more steps and intermediaries within their supply chains, often involving other Asia-Pacific economies.

Challenges of Diversification: Despite efforts to relocate, firms face challenges in achieving meaningful diversification. The limited increase in network density suggests that firms still rely heavily on key suppliers, often located in China, for critical inputs. This dependence complicates efforts to fully leave China.

And in the short term: the increased import prices from alternative locations may contribute to higher U.S. prices and inflation.

Is it possible that in an attempt to hedge against one risk (geopolitical), we not only fail to hedge against it but also create new risks?

When De-risking is Actually Creating More or New Risk

The concept of “de-risking” in supply chains is rooted in the desire to mitigate exposure to various disruptions, be they geopolitical, economic, or environmental. However, the reality of de-risking is more complex, and in many cases, the process itself can introduce new risks or exacerbate existing ones.

Let’s explore how efforts to diversify and reconfigure supply chains can sometimes lead to unintended consequences, creating more vulnerability and complexity.

Increased Complexity and Costs

The recent research by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) highlights that as firms interpose new nodes into their supply chains, the overall distance between suppliers and customers increases. This lengthening of supply chains can result in several challenges:

1. Higher Transaction Costs: Each additional step in the supply chain introduces more points of contact which may lead to new negotiations and potential delays, increasing transaction costs and the possibility of miscommunication or errors.

2. Logistical Challenges: Managing a more complex supply chain requires sophisticated logistics and coordination, which can strain the existing infrastructure and lead to inefficiencies, particularly if new regions lack the necessary capabilities.

3. Increased Lead Times: Longer supply chains may result in longer lead times, making it harder for firms to respond quickly to disruptions or changes in demand. This is particularly problematic for industries with high demand volatility, such as electronics and fashion.

New Geopolitical Risks

While the intention of de-risking is to reduce exposure to geopolitical tensions, the process can sometimes introduce new geopolitical risks, like:

1. Exposure to New Regions: Shifting production to other countries can expose firms to new geopolitical dynamics and risks. These regions have their own political instability, regulatory challenges, or trade disputes that can disrupt operations.

2. Trade Policy Uncertainties: Diversified supply chains can be more susceptible to changes in trade policies and agreements —new tariffs, trade barriers, or shifts in international relations can impact the viability of relocated production facilities.

3. Regional Conflicts: Moving supply chains to different parts of the world can expose firms to regional conflicts or tensions that may not have been as pronounced in their original locations. This can lead to unforeseen disruptions and require additional risk management strategies.

Supply Chain Dependencies

Efforts to de-risk by relocating production can paradoxically increase dependency on certain regions or suppliers, particularly when it comes to critical inputs:

1. Material and Component Dependencies: Even when final production is moved out of China, many firms still rely on Chinese suppliers for critical materials and components. This dependency can undermine the goal of de-risking.

2. Concentration in New Hubs: As firms move production to new regions, they risk creating new hubs of dependency. For example, the concentration of electronics manufacturing in Southeast Asia could create vulnerabilities if these regions face their own disruptions, such as natural disasters or political instability.

Environmental and Social Risks

De-risking can also lead to environmental and social risks, particularly when new production locations don’t have the same regulatory standards as the original ones. These risks include:

1. Environmental Degradation: Setting up new factories in regions with lax environmental regulations can lead to increased pollution and resource depletion. This not only harms the local environment but can also damage the firm's reputation and lead to regulatory backlash.

2. Labor Exploitation: Moving production to countries with lower labor standards can result in exploitative practices, poor working conditions, and human rights violations. This can lead to reputational damage and legal challenges for firms.

3. Sustainability Trade-offs: Efforts to relocate production for cost savings can conflict with sustainability goals. For instance, the increased transportation required for lengthened supply chains can lead to higher carbon emissions, undermining environmental initiatives.

So is it possible to truly de-risk your supply chain?

Is There Such a Thing as Optimal Resilience?

Many firms share that their goal is to build a more resilient supply chain. I’m a skeptic (as long-time readers of this newsletter know) and have been claiming for quite some time that unless something fundamental changes, market dynamics won’t push firms to be more resilient.

But it’s more of an intuition than a well substantiated argument.

Until now…

The paper “Optimal Resilience in Multi-Tier Supply Chains” aims to explore the optimal level of resilience in supply chains with multiple tiers. Given the complexity and interconnectedness of modern supply chains, disruptions can have significant and widespread effects. The authors seek to understand how investments in resilience by firms at different tiers affect the overall supply chain and how these investments can be optimized to improve overall supply chain resilience.

The central question of the paper is how to achieve the optimal allocation of resilience investments in multi-tier supply chains. The authors investigate the differences between equilibrium (market-driven) and optimal (socially optimal) allocations of resilience, and the policies required to align these two.

The authors develop a general equilibrium model with multiple vertical production tiers. The model incorporates:

Endogenous investments in protective capabilities by firms.

Endogenous formation of supply links between firms.

Sequential bargaining over quantities and payments between firms at successive tiers.

The model aims to capture the externalities of resilience investments, where the actions of one firm can affect the entire supply chain. The authors derive policies to achieve the first-best allocation (social optimum) and compare them with equilibrium outcomes.

The paper find that the equilibrium allocation of resilience investments is typically suboptimal due to the externalities involved. Firms do not fully account for the benefits their resilience investments confer on other firms in the supply chain. As a result, the market-driven allocation of resilience is lower than the socially optimal level.

To support firms in effectively relocating their supply chains and building resilient supply chains, the following policies are recommended:

Subsidies for Input Purchases: In the context of supply chain resilience, subsidies for input purchases can be used to counteract distortions in the cost of production that arise due to markups at various tiers in the supply chain. For example, consider a tier-1 firm that purchases inputs from tier-0 suppliers. If the tier-0 suppliers charge a markup, this increases the cost for the tier-1 firm. To ensure that the tier-1 firm considers the social cost rather than the inflated private cost, the government can provide a subsidy to reduce the effective purchase price of these inputs. This subsidy would make the tier-1 firm more likely to buy the socially optimal quantity of inputs, thereby improving the efficiency of the supply chain.

Incentives for Network Formation: Incentives for network formation are critical for enhancing the robustness and resilience of supply chains. For example, firms in intermediate tiers might not form sufficient links with upstream suppliers because they only capture a fraction of the surplus generated by these investments. To address this, the government could provide financial incentives or subsidies to encourage firms to establish more supplier relationships. These incentives would help firms diversify their supply sources, reducing the risk of disruptions caused by reliance on a single supplier. By promoting thicker networks of suppliers, the overall resilience of the supply chain is enhanced.

Direct Subsidies for Resilience Investments: Direct subsidies for resilience investments are designed to encourage firms to invest in measures that protect against disruptions. For instance, a tier-0 firm might receive a government subsidy to invest in advanced protective capabilities, such as better storage facilities, robust infrastructure, or advanced monitoring systems. These investments reduce the likelihood of supply chain interruptions at the very beginning of the supply chain. Given that upstream disruptions can have cascading effects, subsidizing resilience investments at the upstream tiers can significantly enhance the stability of the entire supply chain. The subsidies are typically designed to offset the costs of these investments, making them more financially viable for firms.

These policies should be designed based on the production function parameters of the relevant tier. When transaction subsidies are infeasible, second-best policies require subsidies that depend on production function parameters throughout the entire network. Additionally, subsidies should be larger upstream (earlier in the supply chain) than downstream whenever the bargaining weights of buyers fail to increase along the chain.

The findings have significant implications for policymakers and supply chain managers. Implementing the suggested policies can enhance the overall resilience of supply chains, making them more robust. This is particularly relevant in the context of increasing geopolitical tensions, pandemics, and other global shocks.

Bottom Line

The global shift away from China in supply chain strategies is complex and fraught with challenges. While geopolitical tensions and economic pressures drive the desire to diversify production, the established manufacturing ecosystem in China remains a significant draw. Achieving true resilience and independence from China requires coordinated policy interventions that address the multifaceted nature of supply chain dependencies, cost-quality trade-offs, and regulatory challenges. By implementing these policies, firms can better navigate the difficulties of relocating production and enhance the overall resilience of global supply chains.

While de-risking is an important strategy for firms to mitigate supply chain vulnerabilities, it is not without its own set of risks. The increased complexity, new geopolitical dynamics, continued dependencies, and environmental and social challenges can all undermine the goals of diversification and resilience. Firms must carefully balance the benefits of de-risking with the potential for introducing new risks, ensuring that their strategies are comprehensive and adaptive to the evolving global landscape. By doing so, they can navigate the complexities of modern supply chains and build truly resilient networks that can withstand a variety of disruptions.

Foxconn was also having issues in India - https://restofworld.org/2023/foxconn-india-iphone-factory/

I wonder if any other country can ever match what China can do simply because of the political structure of China.