This Week’s Focus: The Early Impact of NYC’s Congestion Pricing.

New York’s congestion pricing plan has officially been in effect since January 5, so today we’re looking at its early impact from the data available so far. While the policy has reduced traffic in certain areas, it has also led to increased congestion elsewhere, raising the question: Are we truly easing traffic or just relocating it? The collected data highlight notable spillover effects and significant route-by-route differences in traffic patterns. Economically, the plan aligns with classic congestion pricing models, but its ultimate success hinges on alternative transit options, demand elasticity, and political will. But the big question remains: Will the MTA reinvest the revenue into real transit improvements, or will it vanish into a bureaucratic abyss?

A while back, I wrote an article on New York City’s congestion pricing plan before it was implemented. At the time, the policy seemed like a mix of well-intended urban planning, a finance department’s dream, and a commuter’s worst nightmare.

Now that the tolls have taken effect, we have some data to examine—though like most things in NYC, the results are as messy as a midtown street during rush hour.

Let’s start with a real-life example, described by a NY Times article: Lesly Silva, a hospital technician from New Jersey, wasn’t thrilled about the idea of paying to enter Manhattan. However, she’s now saving enough time on her commute to grab a bacon, egg, and cheese sandwich in the morning. That’s peak New York: complain about a policy but appreciate its collateral benefits. “I take my time getting to work now,” she said, highlighting a core goal of congestion pricing—reducing stress and unpredictability in travel times.

The plan went live on January 5, charging most motorists $9 to enter Manhattan below 60th Street. Since then, the data—collected by the transportation analytics firm INRIX—suggests a mixed bag.

This raises a key question: Are we reducing traffic or are we simply shifting it elsewhere?

So what’s the verdict? Shall other U.S. cities roll congestion pricing? Will congestion pricing even survive New York?

Let’s hit the gas and see where this congestion pricing experiment is really taking us.

Early Data: Mixed Signals and Unintended Consequences

While travel times improved in Manhattan’s main congestion zone—particularly on major roads like the FDR Drive and West Street—compared to the same period last year, the overall travel times across the city increased by 3% in the morning rush hour and 4% in the evening.

The data from the first three weeks of congestion pricing in New York City highlight notable spillover effects, as well as significant differences between routes and cities. While the policy has led to reduced congestion in certain areas, it has also shifted traffic to alternate routes, creating new patterns of congestion outside the toll zone.

Spillover Effects—Shifting Traffic Outside the Congestion Zone: One of the most striking outcomes of congestion pricing is the increase in traffic on alternative routes outside of the toll zone. Certain spillover routes, such as FDR Drive and the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel, have experienced increased congestion as drivers attempt to bypass the congestion charge. For example, peak travel times on FDR Drive at 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. have significantly exceeded pre-congestion pricing levels. Similarly, The Route from Washington Heights to Lenox Hill, which captures traffic north of the congestion zone, has seen a steady rise in commute times, reaching up to 46 minutes on some days.

However, not all spillover effects are worsening congestion. Some routes outside the pricing zone, like the BQE, have shown declining traffic levels after three weeks, suggesting that overall driving demand may be decreasing, which implies that some drivers are choosing to forgo trips altogether.

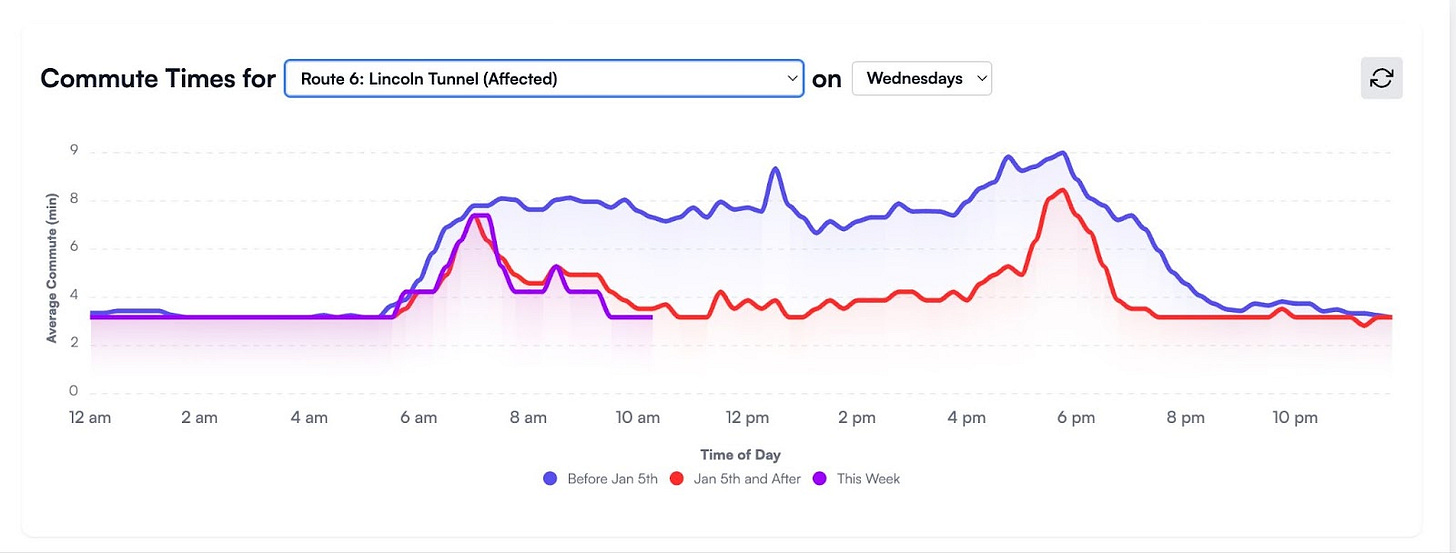

Differences Between Routes—Entry Points vs. Local Travel: The impact of congestion pricing varies significantly depending on the type of route. Major entry points, such as the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels, have seen substantial reductions in commute times. The Lincoln Tunnel, for example, has experienced a notable drop in congestion, particularly during peak morning hours. This suggests that congestion pricing has successfully deterred some car commuters from driving into the city center.

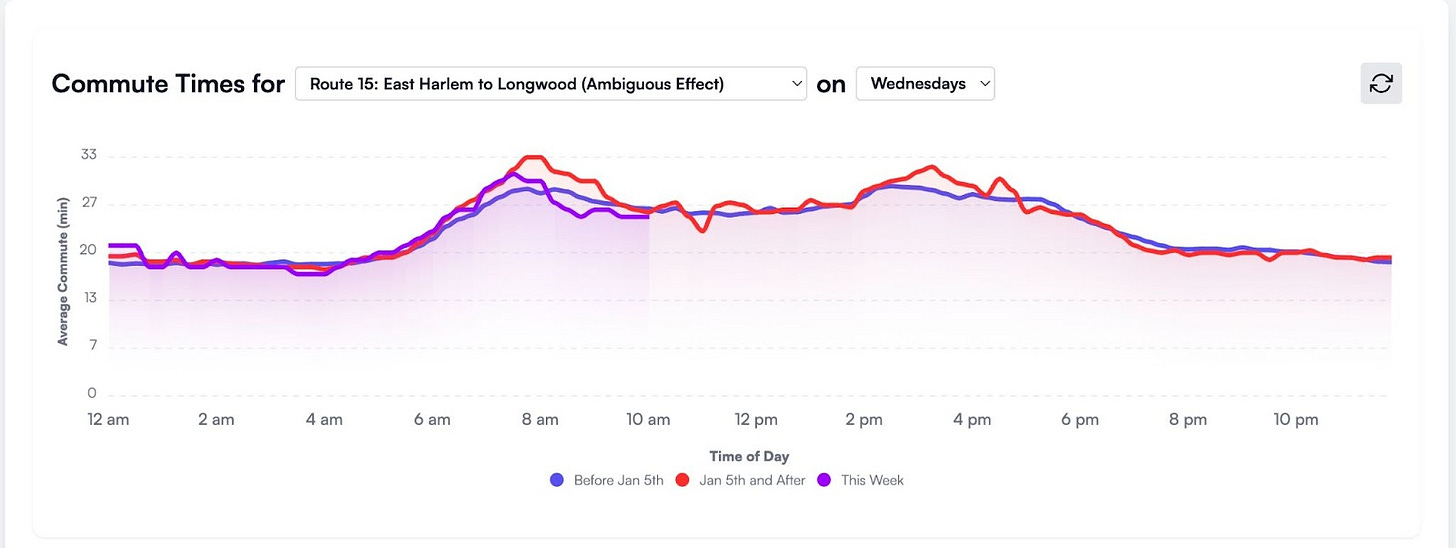

In contrast, routes primarily used for intra-city travel, such as East Harlem to Longwood, have shown little change. Since these roads are not subject to tolls and serve local commuters rather than those entering the congestion zone, the policy appears to have had a minimal effect.

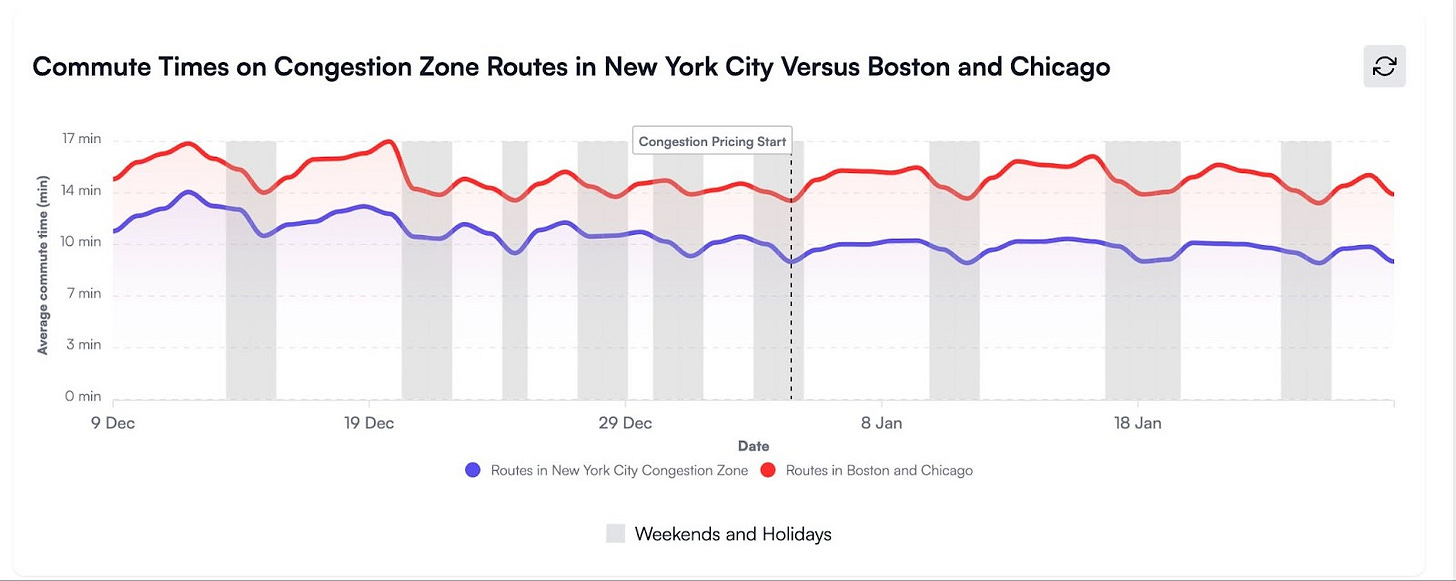

Comparisons Between Cities—New York vs. Boston and Chicago: When compared to control cities like Boston and Chicago, NYC’s traffic patterns have diverged significantly since the introduction of congestion pricing. The gap in commute times between New York and the other cities has widened, reinforcing the idea that the pricing scheme has had a measurable impact. While traffic patterns fluctuate naturally across cities, the increased divergence suggests that congestion pricing is a primary driver of these differences.

While New York has seen some routes clear up and others become more congested, Boston and Chicago have maintained more stable traffic conditions. This contrast further emphasizes that congestion pricing is actively reshaping travel behavior in New York in a way that isn’t occurring elsewhere.

The early data suggests that congestion pricing is achieving its goal of reducing traffic at tolled entry points into Manhattan but is also causing unintended congestion increases on certain alternative routes. While some routes are experiencing higher traffic volumes, others are seeing a decline, indicating that overall driving demand may be adjusting.

Nevertheless, further monitoring is necessary to determine whether current trends persist or if additional behavioral shifts will occur over time.

These mixed results—both statistical and anecdotal—are precisely what the opponents of congestion pricing predicted.

But are these just short-term transition costs or do they reveal deeper flaws in the system?

Effective and Equitable Congestion Pricing

In their research, Ostrovsky and Fang examine the shortcomings of New York City’s congestion pricing plan when it was paused before implementation, and propose modifications to make the policy more effective and equitable.

The authors conducted a policy analysis of NYC’s congestion pricing framework and compared it to congestion pricing systems in other cities, including London, Stockholm, and Singapore. They used economic modeling to evaluate different pricing structures and to propose an alternative congestion pricing scheme that would be both effective in reducing traffic congestion and more equitable to all vehicle types.

The study analyzed New York City’s congestion pricing design, traffic data from the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and DOT, and recommendations from the Traffic Mobility Review Board. In addition, it drew comparisons with international case studies to benchmark potential improvements.

The paper found that prior to its launch, New York City’s congestion pricing plan had significant flaws. The plan disproportionately impacted private vehicle drivers while allowing taxis and delivery trucks to pay significantly less per mile, despite their substantial contribution to congestion (e.g., personal car drivers were required to pay nearly six times more per trip than taxi passengers).

Additionally, the study suggests that New York City’s congestion pricing plan was ineffective because it is both inequitable and politically unpopular. The authors argue that New York City risked repeating London’s mistake, where taxis were exempt from congestion pricing, leading to an increase in empty taxi trips and worsening congestion.

The authors believe that an alternative pricing model—charging all vehicles based on the congestion they create rather than relying on a flat daily fee—would be more effective and fairer. They argued that the plan should be revised to ensure that all vehicle types contribute fairly to congestion mitigation efforts. So instead of charging a single-entry toll, a dynamic per-mile pricing model that adjusts fees based on real-time congestion levels would more accurately reflect each vehicle’s impact on traffic conditions.

The paper’s findings are of course highly relevant to ongoing congestion pricing debates, as they highlight the importance of designing a system that is both politically viable and economically efficient. Policymakers must ensure that pricing structures account for all sources of congestion to maximize the policy’s effectiveness.

The paper was written before the plan went live, and the initial data both aligns with and challenges key claims from Ostrovsky and Yang’s results.

One major finding is the presence of spillover effects—while commute times within the congestion zone have either improved or remained stable, alternative routes like the FDR Drive have become worse. Ostrovsky’s paper anticipates this issue but critiques the policy’s design for disproportionately targeting personal vehicles while allowing taxis, ride-hailing services, and delivery trucks to operate with minimal additional costs. Their claim that these vehicles contribute significantly to congestion appears to be validated by the data, which shows persistent traffic in some areas despite reduced personal car usage. Additionally, while major entry points into Manhattan have seen improved commute times, intra-city travel remains largely unchanged, supporting Ostrovsky’s assertion that congestion pricing should account for vehicles that circulate throughout the day rather than just those entering the city.

Comparisons with Boston and Chicago, where no similar policies exist, suggest that congestion pricing is altering travel behavior in New York but not necessarily reducing overall congestion. While the policy has improved access at key entry points, the emerging traffic redistribution problem (rather than the outright reduction of traffic) raises concerns about its long-term effectiveness.

The data also supports the authors’ recommendation to refine the model and include per-mile or per-trip charges for taxis, FHVs, and delivery trucks, as current toll structures may be shifting congestion rather than alleviating it. To fully optimize traffic reduction, a more balanced fee structure targeting all vehicle types proportionally—rather than disproportionately burdening personal drivers—may be necessary.

Public Opinion on NYC Congestion Pricing Over the Years

But beyond these issues, congestion pricing has its fair share of supporters and opponents—even before its implementation, and more so after.

A study by Chen, Kalan, Ozbay, and Ye investigates how public attitudes and political dynamics surrounding New York City’s congestion pricing have evolved over time.

The authors used Twitter data from 2007 to 2019 to analyze changes in public opinion on congestion pricing in New York City. They applied natural language processing (NLP) techniques for topic modeling and sentiment analysis. Additionally, they identified key political figures and organizations, such as the New York City Mayor, the Governor, and the MTA, based on Twitter engagement patterns.

The dataset consisted of 226,000 tweets from 119,000 users mentioning congestion pricing. To ensure relevance, the authors filtered the tweets to focus specifically on discussions related to New York City, removing data that referenced congestion pricing in other cities. They analyzed public sentiment, key discussion themes, and the role of influential groups in shaping the debate.

The study found that public sentiment toward congestion pricing fluctuated over time. Support was relatively high when Mayor Michael Bloomberg introduced his 2007 proposal, but resistance grew as outer-borough commuters pushed back against tolls. Support for congestion pricing increased again in 2019, driven by declining subway conditions.

The analysis also revealed that small but vocal groups, particularly representatives from the outer boroughs and suburban commuters, played a decisive role in blocking policies. Another major finding was that concerns about congestion pricing shifted over time. Early debates centered on policy specifics, such as pricing zones and exemptions, while later discussions focused more broadly on issues of equity and fairness.

The study also identified influential players in the debate, including the Mayor, the Governor, and various media outlets, which helped shape public perception through their coverage and policy positions.

The findings highlight the growing influence of social media in shaping public opinion and policy debates. To build stronger support for congestion pricing, policymakers need to address concerns about fairness and ensure that accurate information about revenue use is widely disseminated. Consistent public outreach is crucial to prevent sudden shifts in sentiment that could derail the policy.

Overcoming Public Aversion to Congestion Pricing

Regardless of the mixed results, because of the negative sentiment, congestion pricing has many politicians vying to kill it.

A paper by Harrington, Krupnick, and Alberini (1998) examines why congestion pricing remains politically unpopular despite its economic efficiency and explores potential strategies to increase public support for such policies.

The authors conducted a survey-based experiment in Southern California to assess public attitudes toward congestion pricing. Participants were presented with different policy options, including direct congestion pricing, congestion pricing with tax rebates, and high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes. The study aimed to determine whether policy modifications, such as revenue redistribution or allowing motorists the choice between tolled and free lanes, could increase public acceptance.

The research relied on a randomized telephone survey of 1,743 commuters in Southern California. Respondents answered questions about their commuting behavior, demographics, and reactions to various congestion pricing mechanisms. The survey systematically varied policy details to measure how different incentives influenced public support.

The study found that political resistance to congestion pricing largely stemmed from the perception that it was simply an additional tax.

Many motorists resisted the policy because they lacked viable commuting alternatives, making the congestion fee feel coercive rather than optional. However, the study also found that redistributing congestion fees as tax rebates led to a seven-percentage-point increase in public support. Additionally, offering revenue rebates in the form of transportation-related coupons also increased acceptance. The results further revealed that HOT lanes, which provide an option for motorists to either pay for a faster commute or use a free lane, were more popular than full congestion pricing. Support for the introduction of a HOT lane by converting an existing freeway lane increased by 8%, while building a new tolled lane raised support by 17%.

The findings suggest that public opposition to congestion pricing is driven more by perception than by fundamental economic objections.

If policymakers want to successfully implement congestion pricing, they should focus on redistributing revenue in a transparent manner and offer alternative commuting options. Additionally, improving public transit options would help ease concerns by making congestion pricing feel less like a tax and more like a choice.

The study’s insights are particularly relevant to New York City’s congestion pricing efforts, as public resistance has similarly focused on issues of fairness and revenue allocation. Using congestion pricing revenue to lower taxes or offer transit benefits could help make the policy more politically acceptable.

Bottom Line

The data and the studies reviewed here highlight the challenges and opportunities in implementing congestion pricing, especially in a politically complex urban environment like New York City.

So, where does this leave us? Congestion pricing works—kind of…

We see reduced traffic in Manhattan but spillover effects elsewhere. We have some commuters benefiting (faster buses, slightly sane streets) and others suffering (longer suburban drive times). And as always, we have a whole lot of New Yorkers complaining.

From an economic perspective, the policy aligns with the classic models of congestion pricing, but its effectiveness depends on alternative transit options, demand elasticity, and political will. If the MTA reinvests the revenue wisely—fixing delays, expanding service, and improving reliability—congestion pricing could become a long-term success. But if history is any guide, we should probably brace for a scenario where the revenue disappears into a bureaucratic abyss while the 6 train remains as crowded as ever.

In the grand tradition of New York City policies, this one is equal parts brilliant, frustrating, and designed to make someone a lot of money—just don’t ask who.