Lately, I’ve been hearing a lot about how governments should regulate supply chains and enforce more transparency as a way of solving supply chain issues.

But what if governments are not the best option when it comes to supply chain management and, contrary to their intentions, they inflict even more harm on the already fragile and volatile supply chains?

Let’s take COVID tests as a case study.

If you are planning to travel or meet with family members during the holiday season, you are also, most likely, trying to get a COVID test.

While searching the various testing locations, you have probably realized that most are already overwhelmed, making it impossible to find an available slot, and if you are trying to buy a home administered test, you have probably faced a significant shortage there too.

But allow me to explain why I am choosing now, to say that the government is doing a terrible job, when we have already experienced some level of shortage in 2021 for almost every product.

When there is a shortage of iPhones or kettlebells (or, God forbid, coffee grinders), we can still cope (albeit barely, when it comes to coffee). But when there is a shortage of COVID tests, things become a little trickier. Without intending to sound too polemic, in many cases, it might be a matter of life and death.

On the other hand, you may have heard that the US government just announced the distribution of 500 million home testing kits.

The problem is that we don’t have the capacity to manufacture this number of tests in such a short period of time.

The COVID Tests Supply Chain

Let’s try to understand the supply chain for home COVID tests.

The first stage is getting approval from the FDA. Next come firms like Abbott that manufacture and distribute the tests to various selling points. Retailers, such as CVS and Walgreens, then further distribute and sell them to customers, who are the final stage of the chain.

Note that the government could intervene by buying and distributing these tests to customers, or by subsidizing them and reducing their costs. But maybe that’s just me and my wishful thinking.

I claim that what we are seeing here is a typical bullwhip effect.

The term is commonly used, but rarely explained. The bullwhip effect is the amplification of demand variance as one moves further upstream in a supply chain from the source of noise and volatility (i.e., the customer). More specifically, in any node of the supply chain, the variance of orders is larger than the variance of sales.

So, everything starts with the customer.

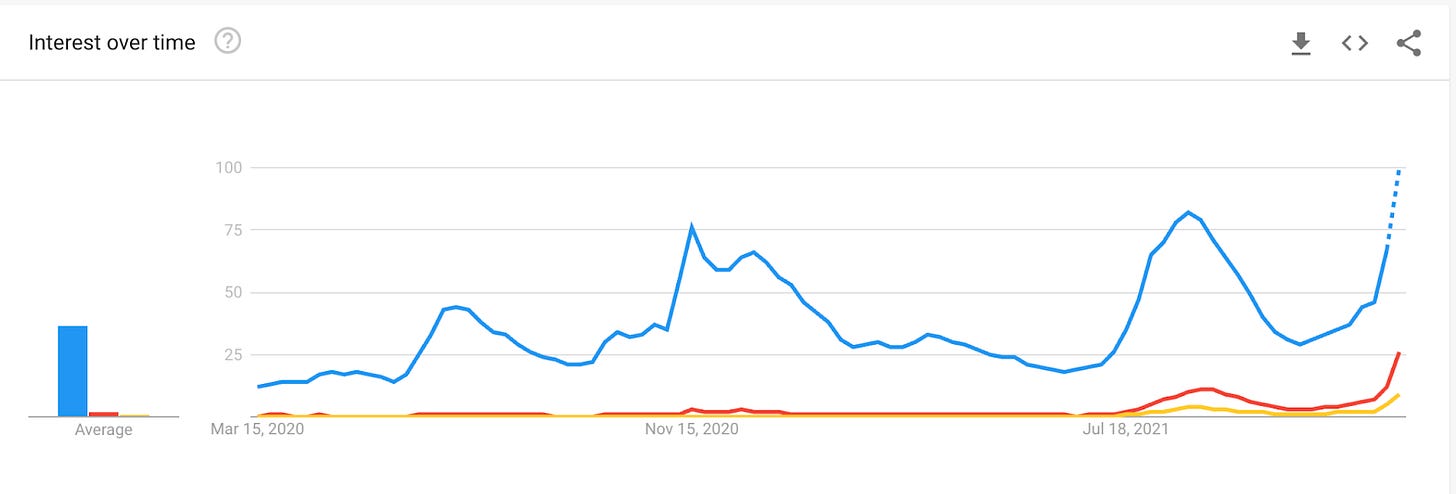

I don’t have accurate data on customer demand, but Google Trends is a good proxy.

As we can see from the three graphs, COVID test (blue), home test (red), and the Abbott test (yellow), all rise and fall following the different waves. We see a spike in July when the Delta variant emerged, and another spike now with the Omicron.

Home tests are new, but we can already see that they are quite a sizable part of the market, and even noticeable when compared to the general search term (covid tests).

It is easy to see how demand increases and decreases based on the number of incidents and emergence of various variants:

And this is expected. People may casually stock a couple of home tests during quiet times, but as soon as new variants surface, demand surges.

The problem with such a sharp increase in demand is that we don’t have enough of these tests to accommodate it:

“There are a few reasons why these rapid antigen tests are suddenly so scarce. Workplaces and schools bought many of the available rapid tests in bulk earlier this year to speed up their reopening efforts. Resellers, meanwhile, are stockpiling supplies to capitalize on the spread of omicron.”

To try and understand why variance propagates up the supply chain, it’s enough to look at customer behavior.

When customers realize that there is a surge in demand, their immediate response is to hoard tests as soon as they see them. So, customers not only experience the volatility, but they end up amplifying it by their own behavior.

The retailers’ solution is to ration the tests:

“Customers are limited to four over-the-counter antigen tests at Walgreens pharmacies, while CVS is restricting buyers to six kits.”

But when you ration things, people tend to order more than they need, creating even more distortion in the supply chain.

Again, you take the existing volatility and multiply it even further. In addition, if retailers are monitoring clickstream data, and using it to estimate demand, they will probably see even more clicks than the real demand. Why? Because everyone is visiting every available online source, knowing that any single source is rationing.

The demand the manufacturers are currently seeing is probably the peak and completely distorted…And will of course die when Omicron subsides…until we get to Rho.

The Root Cause

But why is there a shortage of home tests? Why can’t we just manufacture the 500 million kits Biden promised?

“There are a lot of components that go into an at-home testing kit. ‘The packaging, the testing strip itself, the cotton swabs, the fluid that you use to administer the test,’ said Gigi Gronvall at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. ‘There’s been issues getting the cotton swabs, the nitrocellulose that’s used for the testing strips,’ Gronvall said.”

But the roots go deeper than that. ProPublica had a story in November (even before Omicron), on how the government botched the home-kit test market.

Initially, the FDA made it very hard to get home tests approved and only relied on very few firms, Abbott being one of them. The article discusses the difficulty smaller players faced in having their tests approved, and alleges for some improper prioritization.

The situation became worse when the FDA signaled the efficacy of the vaccines and the fact that we are seeing the end of the pandemic. Why would that matter?

“In May, the CDC leaned hard into the message that vaccines were almost completely protective, mitigating the need for frequent testing. Manufacturers took that as a bad sign for testing volume. Abbott ramped down manufacturing of its popular home test.”

Both the manufacturers and the public make decisions based on signals, the noisier these signals are, the less optimal the decisions become for the system as a whole. In a situation with no volatility, this can be mitigated. In situations with a lot of uncertainty, these decisions make the situation much worse.

I know that none of this is intentional, and I know there is also a political angle to it. But it doesn’t make it better.

So the government, with its actions, has made the shortage worse. It didn’t cause the surge in demand, but it definitely increased volatility in the supply chain.

Can the Government Fix this?

There are a few things that can be done to improve the situation.

The federal government can purchase large quantities from companies that are able to manufacture home tests in bulk, and then offer them to end-customers at low or no cost.

Basically, the government can commit to buying home tests from any firm that is able to meet the necessary standards and is willing to manufacture them.

As we can see from the graphs above, demand for home tests is quite volatile. When trying to decide on how much inventory to carry, retailers such as CVS need to balance the risk of overstocking and understocking. In order to do so, they usually target a certain service level (e.g., a level of 95%). In this case, the firm carries the average demand plus a certain amount of safety stock (for a level of 95%, this will amount to approximately 1.6 times the standard deviation of demand).

I am not an epidemiologist, but I would expect the government to be more risk-averse than a regular firm when it comes to inventory and the possibility of stocking out on products. If it’s too expensive for a firm to offer a service above 95%, I expect the government to be willing to tolerate the additional cost of a service level north of 99%. For 99%, the government needs to carry 2.3 times the standard deviation of demand. For 99.9% service level, it needs 3 times the standard deviation. In the middle of a pandemic, this doesn’t strike me as too much.

The government can also centralize inventory and distribution. While CVS needs to carry safety stock in every store, even in areas where there is no outbreak, the government can mobilize these tests to areas of need, and instead, carry safety stock at a national and not a local level.

The government has the scale to deliver these tests quickly and efficiently.

But knowing how reluctant the US governments have been in trying anything too “socialist,” expecting something like this would be almost un-American.

It is quite symbolic that 2021 is ending with a mega shortage, in the midst of a mega pandemic that defines our current century (I tried to fit more buzzwords into this sentence, but Substack rejected them).

Supply chains and COVID. COVID and supply chains.

This is the final post of the year.

A year that gave supply chain experts and researchers a lot to think about and even more to work on. But I think, and I am sure that I am talking on behalf of many of my colleagues, that we are all more than ready to get back to supply chain obscurity.

Wishing everyone a happy and healthy 2022.

Great insights on the supply chain origins of the Covid test kit shortages. Wishing you a happy, healthy and more obscure 2022!!

Great post Gad. Very helpful explanation for me. I wish I was the person who planned ahead and bought a few tests during periods of calm but I am not. Happy new year!