Delta to Pay Flight Attendants for Boarding: It’s About Time

A couple of weeks ago, Delta Airlines announced that, effective June 2nd, it will increase boarding time for its single-aisle, narrow-body planes (which are used for domestic flights) from 35 to 40 minutes.

The decision was made to allow more time for passengers to board and safely store their hand-luggage on the plane, and in order to further improve Delta’s on-time performance.

I am among those who stand in line, ready to board, 15 minutes before the boarding process begins (yes, you know me by now), so I find this a very positive development. Even though I don’t fly Delta, I hope other airlines will soon follow.

The article mentions a series of changes that Delta is planning to implement, but in my opinion, the most interesting one is that, from now on, flight attendants will be paid for that boarding time.

Unless you follow the airline industry, you may not know that boarding pay for flight attendants is not typical for most airlines, and this has indeed been a cause for contention in every negotiation the airlines have with their flight attendants. Especially when pilots are being paid for this time.

Why Now?

Why is Delta taking this step to pay its flight attendants for boarding time?

The first, obvious answer and the one that Delta acknowledged, is that flight attendants cannot be required to be present for any additional period of time before the flight, without additional compensation.

And indeed, it seems trivial. In fact, it’s pretty shocking that airlines have not paid flight attendants until now for something that seems like such an integral part of their job.

The second reason is that airlines have been suffering from significant crew shortages, which have caused considerable flight delays and cancellations. This is an opportunity to move closer to crew members and maybe even manage to poach some workers from other airlines.

A third reason is that Delta’s flight attendants are not unionized. For over twenty years, the unions have failed to negotiate this boarding time pay into their contracts. With a growing effort toward unionization across the country, this is an attempt by Delta to fend off this possibility and remind their workers that they can get benefits even without a Union.

And indeed, the AFA United came out with a statement:

“It’s a stark reminder that Delta management, in the same manner in which it was implemented, has the ability to unilaterally end the boarding pay, at their sole discretion, in the same way a bi-weekly pay methodology was implemented forcing Delta Flight Attendants to fly within every two-week period in order to maintain benefits and to get a paycheck. This will continue to be the case until that time when Delta Flight Attendants vote for Union representation.”

The Role of On-Time Performance

While the reasons Delta Airlines is moving forward with these changes may be somewhat evident, I would like to go deeper and understand the connection between the increase in boarding time, on-time performance, and the additional pay.

So let’s first start with the definition of on-time performance. Since the airline industry’s deregulation in 1978, the federal government has collected and published data on the percentage of flights that arrive within 15 minutes of their scheduled arrival.

And as you may expect, given the new announcements and additional boarding time, Delta is the airline with the best on-time performance, well above other legacy airlines, with 87% of its flights arriving on time.

So starting the boarding process earlier is clearly an effort on Delta’s part to maintain this dominance.

But this raises the question of which part of these delays are driven by airlines and, more specifically, which part of these delays can be affected by the flight attendants.

Since all US carriers fly through different airports and regions (but with significant overlap), I think it’s important to understand the leading causes of these delays.

Taken from the website of the Bureau of Transportation Statistics:

It is clear that on average, 77% of the time, flights are on-time. And regarding delays, 7.3% of the time, a delay is due to the air carrier, and 6% of the time it’s due to the aircraft arriving late.

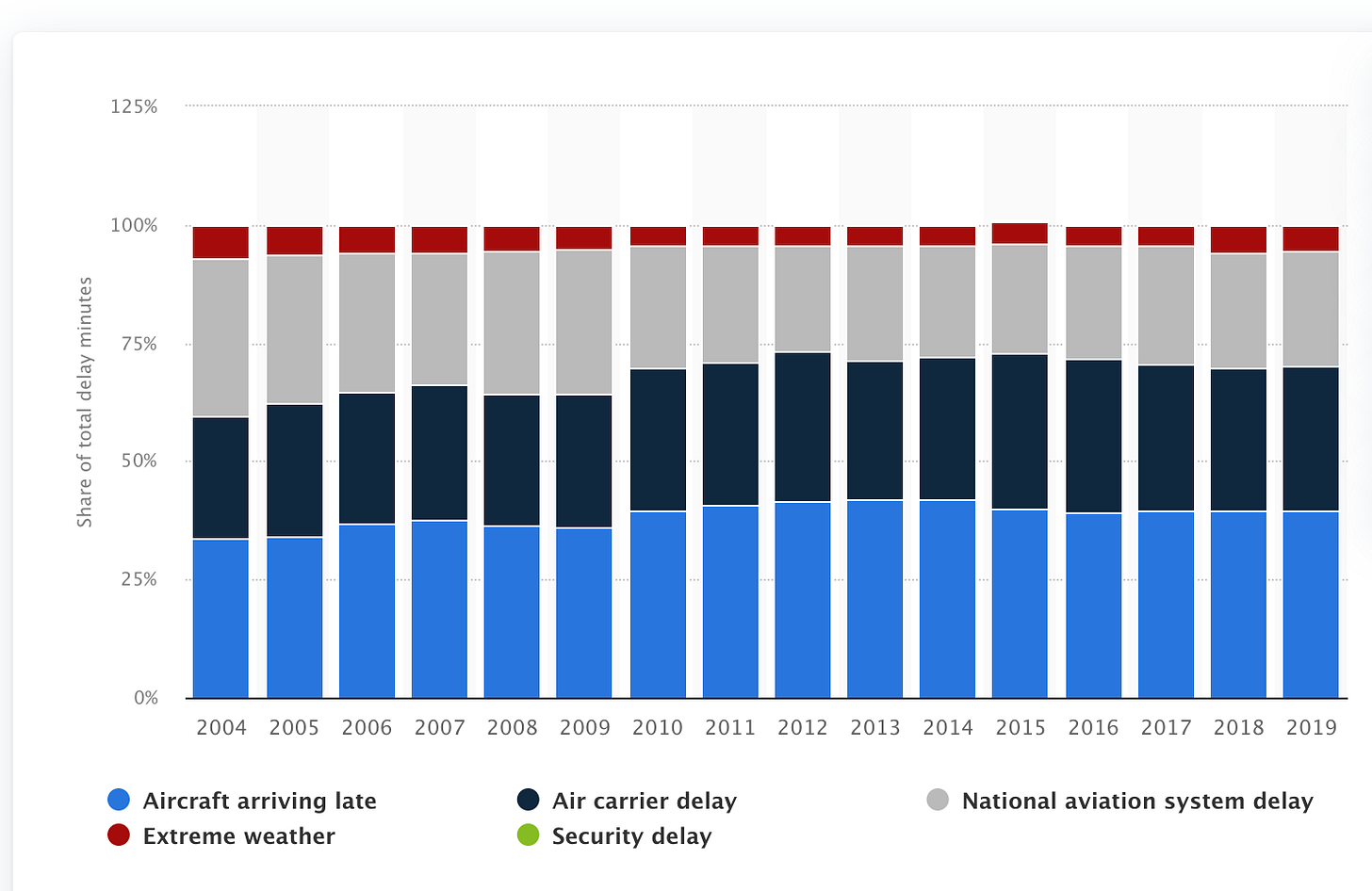

So looking only at the delays, we see that a plane arriving late causes 40% of the delays, while 30% of delays are caused by the airline itself, i.e., the plane and the operations concerning the specific flight. As you can see in the following graph, there is very little change over the last 15 years (pre-COVID):

These statistics highlight two critical aspects:

First, making sure the flight leaves on time reduces the likelihood of the flight being late. Second, ensuring that the flight arrives on time significantly increases the probability of the next flight also being on time.

So any effort to leave on time will go a long way toward having a better on-time performance for the entire airline.

And with this, we return to the second part of the question I previously raised: the flight attendants’ role in ensuring that a flight leaves on time.

Part of it is obvious: the flight attendants can be instrumental in helping passengers navigate the jigsaw of fitting their luggage into the overhead bins and expediting the boarding process. I am sure you have been on flights with very diligent flight attendants that manage to fit everything and ensure that everyone is seated and ready to leave both in a smooth and efficient manner. I am also sure you have been on some flights where this was not at all the case.

And indeed, most airlines offered bonuses to flight attendants for being on time (even if the bonus was minimal).

Now, note that boarding pay is about the scheduled boarding time (and not the actual boarding time), so if it takes longer to board, the flight attendants will not be paid more. So at least in the short run, boarding pay will ensure that flight attendants become more motivated since their time is now paid and appreciated.

But I think there is another reason that Delta, and hopefully other airlines, feel pressured to start boarding earlier and to pay their flight attendants, and it’s related to other mitigation and effects of on-time performance.

Over the last few years, airlines have realized that, as airports become more congested, it's harder to be on time and to leave on time.

Their solution was to add buffers; what some people call “strategic padding.” Padding, or schedule padding, is the amount of “additional” time added to the schedule of a flight.

It is essentially a buffer that prevents the next flight from being delayed, and airlines basically started to artificially post longer flight times to ensure on-time performance.

This is related to the theory illustrated in a book I frequently reference, The Goal, that the cause of delays is the combination of statistical fluctuations and dependent events. As statistical fluctuations increase, it is essential to add these buffers.

And indeed, Van Mieghem, Salant, and Zhang study the problem of increased flight duration (specifically, increase in posted flight duration) and conclude that:

“This paper considered four potential drivers of the increase in posted flight duration over a 21-year span: an increase in average air-time, an increase in average ground-time, an increase in variability padding, and an increase in strategic padding. We established that the increase in strategic padding and in average ground time are the two key drivers of the increase in posted duration. Air-time and variability padding neither significantly increased, nor affected the increase of posted flight duration, over the 21-year span.”

And the following graph tells an amazing story:

Flights became longer over this time period due to multiple factors, but the main ones are ground time and strategic padding.

Ground time has increased due to airport congestion, and since it starts counting after the moment the doors are closed and the breaks are lifted, it is part of the flight attendants’ payment (even before the new change).

But strategic padding is interesting because for airlines, this is wasted time and with it, capital. Airlines make money when planes are in the air and lose money when the aircraft is on the ground. Padding means that the aircraft will spend less time in the air and more time on the ground (usually at the destination) in order to create this buffer.

As far as I understand, airlines pay their flight attendants based on the actual flight time and not the posted time. So as long as the doors of the aircraft remain closed, they are being paid for delays, but not for the padded time (since this is only a buffer which is rarely used). If the flight arrives ahead of the scheduled/posted time, flight attendants will not be paid for that interval, but the capital associated with the plane is still lost.

So the effort to move boarding time will most likely lead to less padding (in equilibrium), and the airline is betting that the additional time for boarding, along with the extra pay, will be offset by the less time needed to pad the flight time.

Will this indeed be the case? Only time will tell.

Furthermore, since Delta is more “on-time” than any other airline, it will “push” other airlines to make similar changes, and ultimately pay more onboarding time.

In other words, for Delta, paying for flight attendants is much more operationally aligned than any other airline, at least until the others manage to catch up.