A few weeks ago, the NY Times published an article on the significant delays of asylum cases due to the “severe shortage of immigration judges.” The article was written following a new surge of migration with the end of Title 42 pandemic restrictions.

Before I continue, I would just like to say that regardless of your political leaning, you should care about justice being done and being done promptly.

Just to offer an idea of current wait times:

“The backlog of immigration cases in the courts grew to one million in 2019 during the Trump administration, but it has increased since then to more than two million cases, according to data collected by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University. The average time it takes to close an immigration case is about four years, according to the database. But some judges say they have cases that have been pending for more than a decade.”

To put things into perspective, here is the total number of pending cases across the US:

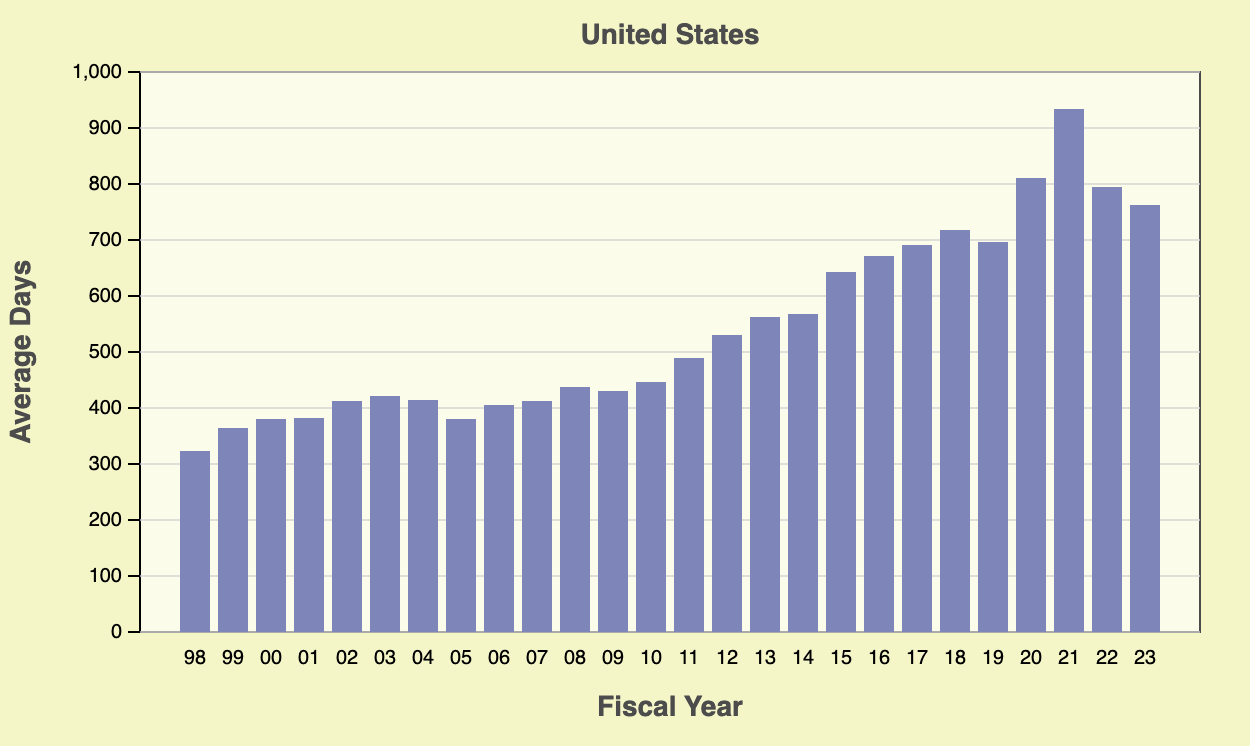

And the average waiting time (in days):

So, while there is a slight decline, the overall wait time is very high —close to 800 days, on average, in 2023.

Is this Necessarily Bad?

For some, letting people wait might seem like the right thing to do because queues serve four critical functions:

First, queuing systems institutionalize interest, enabling the government and potential rights holders to strategize, allocate resources, and project their actions into the future. This structure ensures systematic planning and an orderly manner of achieving goals.

Second, queues establish precedence, constituting a hierarchized waitlist. Often, individuals demonstrate heightened concern toward the principle of fairness, specifically with regards to those attempting to evade the wait by bypassing the queue — a phenomenon known as "queue-jumping"— compared to their wait time.

Third, queues foster reliance and equal opportunities, underlining the value of patience over financial capability. This aspect is critical in redefining societal norms, shifting away from a pure monetary value of resources to include time as a valuable commodity expended during the waiting period.

Fourth, queues expedite the realization of rights, connecting them to the actual acquisition of the promised entitlement, which, in turn, compels governmental expenditure. This mechanism provides a tangible aspect to otherwise abstract rights.

In other words, queues are a system where you pay with your time rather than with your money. So in America, it seems that people’s desire to live in this country is measured by how long they are willing to wait…

But the issue is more complex when it comes to immigration cases related to asylum: asylum seekers are not regular immigrants and since they’re seeking asylum, there’s no way of knowing who’s legitimate and who’s not, unless they are interviewed.

“This is a great tragedy because it creates a second class of citizens,” Ms. Klein, who started working as an immigration judge in the Clinton administration, said of those immigrants who have been waiting years for an answer to their case. The oldest case Ms. Klein ever adjudicated had been pending in the court for 35 years, she said.”

These delays are more than just a matter of inconvenience. They have a real and tangible impact on the lives of those being judged.

First, uncertainty and prolonged stress can have severe psychological repercussions. A study published in the Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health found that prolonged immigration proceedings can lead to increased levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Second, these delays may have significant economic implications. While awaiting judgment, many immigrants are unable to work legally, leading to financial instability and hardship. This not only affects the individuals but has broader economic implications, as potential contributions to the economy are lost.

Moreover, the delays can disrupt family unity. Often, family members may be separated during lengthy court proceedings, causing emotional distress and other practical difficulties.

In other words, the impact extends far beyond the courtroom. It is a crisis that affects individuals, families, communities, and society as a whole. As such, it is a problem that deserves our urgent attention and action.

A Solution that Made Things Worse

I would argue that the delays also impact the broader legal system. The backlog strains court resources, leading to rushed hearings which potentially compromise the quality of decisions. This could potentially lead to miscarriages of justice, undermining the integrity of the legal system.

To understand this, we must look at the solution currently being used.

Usually, in situations of significant backlog, creating priorities for those in greater need solves the issue, but not in this case. The Biden administration tried to resolve this issue by creating a dedicated docket:

“The Biden administration placed about 110,000 cases involving new arrivals on a dedicated docket, with the aim of finishing them within a year. About 83 percent of those cases were closed but just 34 percent of the migrants found representation, according to the Syracuse database. Migrants have the right to an attorney, although the government is not required to pay for legal representation. Only 3,000 of the migrants were granted asylum.”

And indeed, the vast majority of cases was closed within 300 days and the queue for this dedicated line no longer grew:

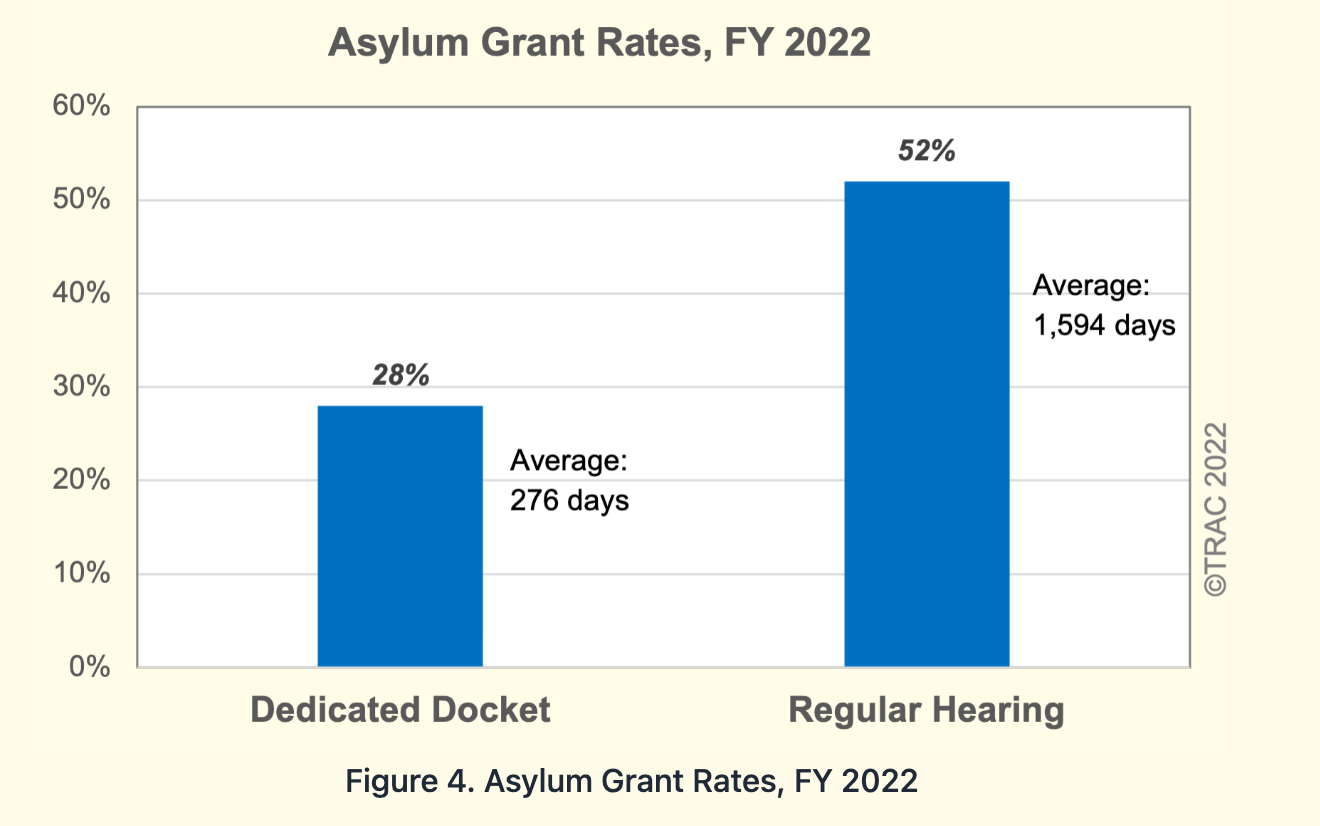

The problem was that only a few were actually granted asylum:

And the percentage of cases that were granted asylum through the dedicated docket is far below the percentage of those that went through regular hearings:

What’s Causing the Denials?

Judges are influenced by the length of “the line,” and there’s also significant evidence that they are harsher when the line is longer. And this is interesting: not only does a longer line increase the wait time, but it also affects the behavior of the service provider charged with managing the queue.

This is exactly what Jason Best and Lydia Brashear Tiede found in their paper Vacancy in Justice: Analyzing the Impact of Overburdened Judges on Sentencing Decisions:

“Policymakers and scholars repeatedly warn that frequent and persistent judicial vacancies pose one of the greatest threats to the federal judiciary by overburdening judges. Scholars, in turn, are divided as to whether pressure on judges results in more lenient punishment. Despite such concerns, the effect of vacancies is rarely tested directly and related studies generally fail to account for issues of endogeneity related to vacancies and caseloads. We address both concerns by using an innovative instrumental variables strategy and unique data, consisting of over 400,000 cases to test vacancies’ effects on federal district court judges’ sentencing decisions. We find that overburdened judges take shortcuts, such as using focal points and cues, resulting in harsher sentences. The analysis has significant implications for those concerned with civil liberties and taxpayers who must shoulder the financial costs of incarceration.”

The phenomenon that workers in the queue respond to the length of the line is not only true for the legal system but also in health care. My colleague Christian Terwisch together with Diwas KC wrote a paper showing similar results in health care:

“Using operational data from patient transport services and cardiothoracic surgery — two vastly different health-care delivery services — we show that the processing speed of service workers is influenced by the system load. We find that workers accelerate the service rate as load increases. In particular, a 10% increase in load reduces length of stay by two days for cardiothoracic surgery patients, whereas a 20% increase in the load for patient transporters reduces the transport time by 30 seconds. Moreover, we show that such acceleration may not be sustainable. Long periods of increased load (overwork) have the effect of decreasing the service rate. In cardiothoracic surgery, an increase in overwork by 1% increases length of stay by six hours. Consistent with prior studies in the medical literature, we also find that overwork is associated with a reduction in quality of care in cardiothoracic surgery — an increase in overwork by 10% is associated with an increase in likelihood of mortality by 2%. We also find that load is associated with an early discharge of patients, which is in turn correlated with a small increase in mortality rate.”

Essentially the same situation with the immigration system: With limited resources, faster service due to long lines results in worse and unfair service.

Is There a Solution?

Addressing court delays while maintaining fairness in immigration courts requires a multi-faceted approach.

Here are some potential solutions that can help alleviate the backlog and improve the efficiency and fairness of the system:

Expanding court capacity: Increasing the number of immigration judges is essential to address the growing caseload. Hiring more judges allows courts to manage more cases simultaneously, thus reducing backlog and wait times. Additionally, establishing new immigration court locations or expanding existing ones can help distribute the workload more evenly.

“Mr. Biden has made some progress — hiring more than 200 judges since he came into office — but is still falling short on his campaign pledge to double the number of immigration judges. Some of the judges will be working seven days a week for a time while the administration confronts the new surge, according to the Justice Department.”

But increasing capacity requires increased funding. Providing adequate funding to immigration courts is crucial to support their operations. The additional resources can be allocated to hiring more judges, support staff, and interpreters. This will help reduce the workload per judge and enable courts to process cases more efficiently.

But if you follow politics, you know this is not simple.

“In his 2023 budget request, Mr. Biden requested funding to hire 200 more judges. Congress only appropriated funds for an additional 100 judges, for a total of 734 positions. The government is still working to fill the slots.”

Streamlining processes: Simplifying and streamlining court processes can help expedite case resolution. This can involve implementing electronic filing systems, utilizing technology for remote hearings, and improving coordination among government agencies involved in immigration proceedings. Such measures can help reduce administrative burdens and help case management become more efficient.

“Typically, after migrants cross the border, they are questioned by an asylum officer to determine if they have a credible fear of persecution at home. After meeting the standard, many are released into the United States and wait years until they are heard in court.”

However…:

“Most asylum applications are not granted, even if a person passes the initial credible-fear screening. Migrants must meet a much higher standard in court to be granted asylum, proving that they were or would be harmed based on their race, religion, nationality or political opinion. Fleeing solely for economic reasons does not make a person eligible for asylum.”

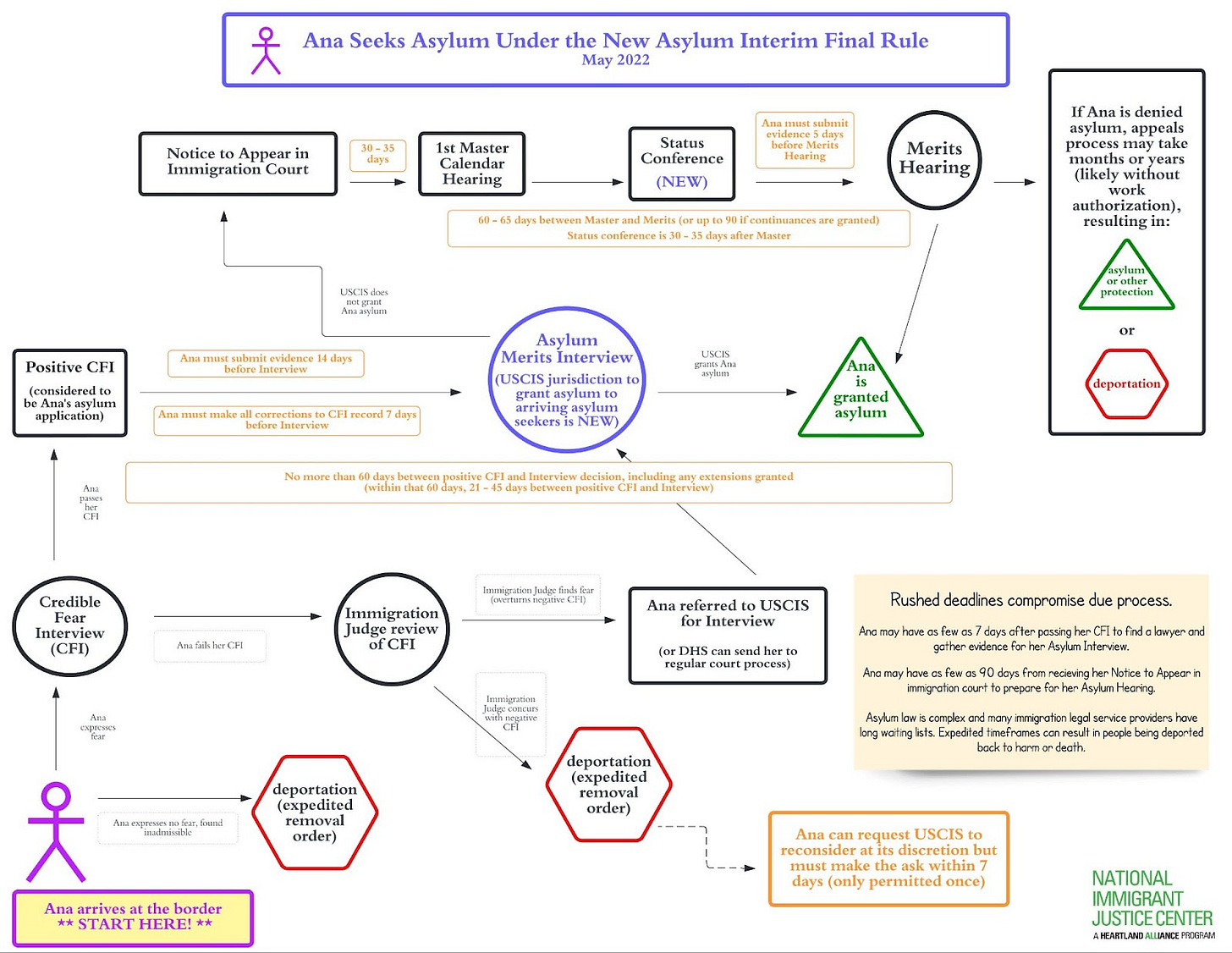

And this is what the process looks like:

In this revised process, speed is indeed being prioritized, but it absolutely compromises fairness, as the applicant not only has limited time to prepare, but also limited access to an attorney.

So maybe the bottleneck doesn’t only concern the overall number of judges but also the ability to provide legal assistance and representation. Providing legal assistance and access to counsel for individuals in immigration proceedings is crucial. Many immigrants navigate complex legal processes without representation, contributing to delays and decreasing their chances of success. Increasing the funds for legal aid organizations and promoting pro bono representation can help ensure individuals have access to legal support.

Prioritizing vulnerable populations: Identifying and prioritizing vulnerable populations, such as asylum seekers and individuals with urgent humanitarian needs, can help expedite their cases. Creating specialized dockets or fast-track processes for these cases can ensure timely resolution and prevent unnecessary delays. The fact that the current attempt to prioritize isn’t working doesn’t mean that any attempt won’t work. So apart from prioritizing these cases, we must also provide the right tools for judges and asylum seekers.

And finally,

Comprehensive immigration reform: Addressing the root causes of court delays requires comprehensive immigration reform. Reform measures should focus on creating a fair and efficient system that balances border security with humane treatment, reduces unnecessary detention, and provides clear pathways for legal immigration. By addressing underlying issues, such as outdated policies and backlogs, comprehensive reform can help alleviate the strain on immigration courts.

But this is outside the scope of this article.

Remember, improving access to justice and reducing court delays in immigration courts is not only a legal imperative but also a reflection of our commitment to fairness and human rights. And while in most queuing systems the objective is to speed up the process, the policies and solutions that are right for amusement parks and fast food chains may have adverse consequences for the justice or health system.

One question for "What’s Causing the Denials?": if judges are harsher for longer lines, why the shorter line (Dedicated docket) seems to get punished more (lower grant rates)?

Gad, thank you for a challenging and thought provoking article.