With inflation soaring and price increases across the board —from food to flights, it was interesting to see that gas prices this past week were…negative…in Europe.

As the following graph shows, this is a great relief after the extremely high prices that prevailed during the summer and the beginning of fall:

As we all know, the price increases were driven by Europe’s reliance on Russia for its gas supply, and the severance of this relationship due to the war in Ukraine.

But what drove the sharp price decrease?

There are many reasons for that:

The most important one has been the slowdown in demand. Why has demand slowed down? Some factors are exogenous and not directly related to the issue, while others are more endogenous.

By exogenous, I mean the fact that the weather in Europe hasn’t been all that cold, thus demand for heating gas has remained low.

By endogenous, I mean the fact that the high prices themselves have reduced demand.

There is another endogenous factor, which is related to the expected high prices, but also a consumer behavior change as a defensive mechanism to the root cause of all of this, the war in Ukraine:

“Most impressive of all has been the reduction in consumption of gas by both industrial and domestic consumers, not merely related to the mild weather. In recent weeks, Germany’s industrial use of gas has been around 20 to 25 per cent down on a year ago while its production in the sector was 2.1 per cent higher in August year on year. German household gas consumption is down similar amounts as families compete to see how far into autumn they can go without turning on the heating.”

Basically, consumers watching the news and looking at their meters, realize that they need to use less energy. On top of that, an ordinance in Germany states: “Retail stores may no longer keep their doors open throughout the day to reduce electricity consumption for air conditioning when it is hot outside — and for heating on cold winter days.”

Not All Good News

So all of this sounds good, right? … Right?

Not necessarily.

Part of the problem is that Europe has too much inventory. Actually, that may not be entirely accurate. What’s clear is that it doesn't have enough storage capacity to carry any additional inventory:

“The European Union has also built substantial buffers against any further supply cuts by filling gas storage facilities close to capacity. Stores are now almost 94% full, according to data from Gas Infrastructure Europe. That’s well above the 80% target the bloc set countries to reach by November.”

So in the same way Amazon runs promotions to clear its inventory and create room for new products, the negative gas prices are aimed at making room for the gas that is currently waiting on ships, tens of which are waiting to offload (liquified) natural gas at European storage facilities.

To understand how severe the issue is:

“About 10% of the LNG vessels in the world, 60 tankers, are sailing or anchored around Northwest Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Iberian Peninsula, according to MarineTraffic. The vessels are considered floating LNG storage since they cannot unload and the situation is impacting the price of natural gas and freight rates.”

It’s important to note that this is different from consumer retail products. In retail, firms set discounted prices to clear working capital and shelf space from previous seasons and introduce products from the new season, knowing that the willingness to pay is going to be higher for these new products. This is not the case here. These lower gas prices are not optimal in terms of “social welfare.”

What’s Next?

All of this started with the war in Ukraine, and the impact of having Russia as Europe’s main supplier of gas and energy. So the source of volatility here is the supply, rather than the demand side (as we usually see).

My prediction is that we will likely see energy prices going up again. Unlike some commentators, I don’t think the end is in sight, and here’s why:

First, as you already know, winter is coming… It’s hard to predict how cold this winter will be, but the impact of climate change has not only been a shift of the averages (an increase in temperature), but also an increase in the standard deviation. I am not an expert on climate change, but this article helps shed some light:

“The frequency of climate extremes will change in response to shifts in both mean climate and climate variability. These individual contributions, and thus the fundamental mechanisms behind changes in climate extremes, remain largely unknown. Here we apply the probability ratio concept in large-ensemble climate simulations to attribute changes in extreme events to either changes in mean climate or climate variability. We show that increased occurrence of monthly high-temperature events is governed by a warming mean climate. In contrast, future changes in monthly heavy-precipitation events depend to a considerable degree on trends in climate variability.”

As you know from previous posts, if there is anything that supply chains “hate,” it’s volatility, and one way to deal with that uncertainty is buffers and inventory. So, we know that the weather will get worse, and we know that Russia will continue to flex its muscles even more, so why not get more inventory?

Because there isn’t enough storage.

Why isn’t there enough storage?

Well, because most countries didn’t think it was important to build and invest in it:

“According to the European Commission, total available EU gas storage capacity is 1110.7 TWh (equivalent to 113.7 bcm), which is less than overall annual gas imports from Russia. Storage capacity is not evenly distributed across the EU (see Figure 2), with five countries accounting for almost three quarters of the total (Germany, Italy, France, the Netherlands and Austria), while around a third of smaller EU Member States have no storage capacity of their own”

So given this lack of inventory and the expected increase in volatility, what should we expect for the European consumer moving forward? And is this volatility going to be felt even more by consumers or less?

We are all familiar with the bullwhip effect, where minor volatility of demand in supply chains becomes amplified the further you move upstream. But the situation here is different. We’re not talking about order quantities, but rather about prices. There is a term for this as well:

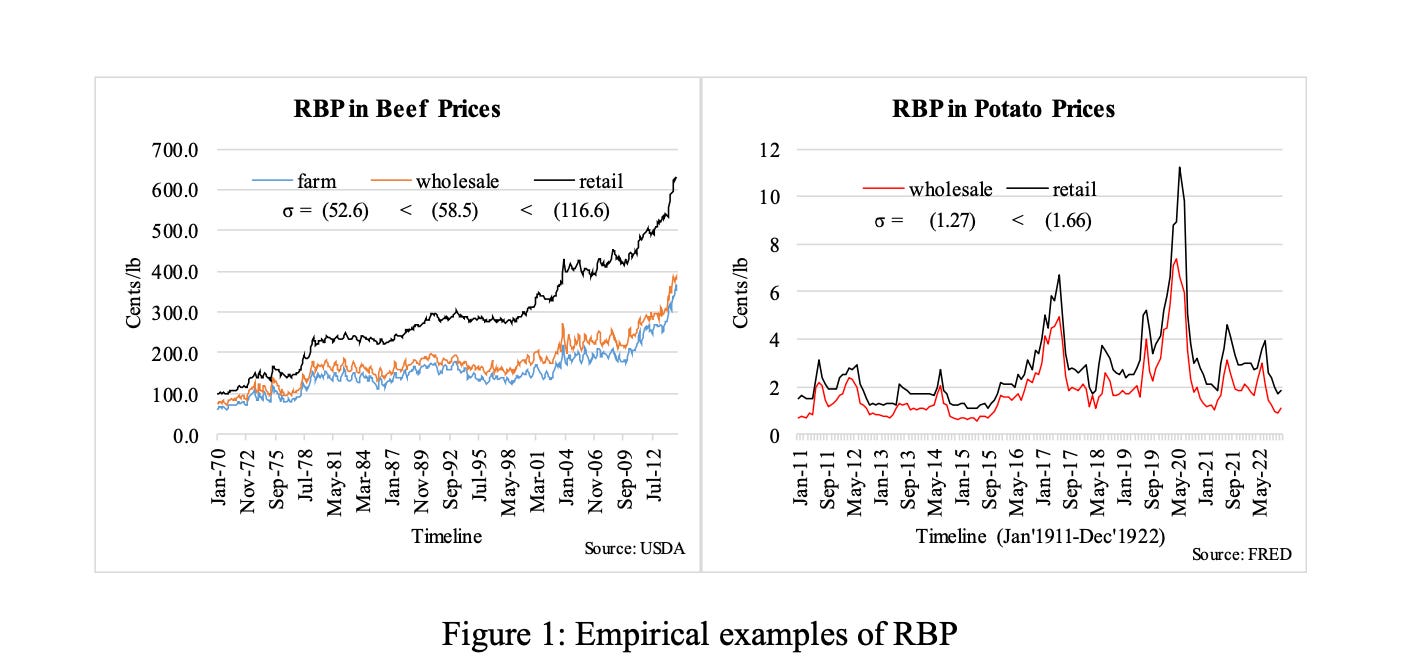

“A ‘reverse bullwhip effect in pricing (RBP)’ occurs when an amplification of price variability takes place moving from the upstream suppliers to the downstream customers in a supply chain.”

The evidence for this behavior comes from the commodity prices of beef and potatoes:

What’s “reverse” about it? Price volatility amplifies the closer you get to the consumer.

But unlike the bullwhip effect, which is more or less predictable, the question of whether the pricing effect increases or decreases as you get closer to the consumer is not as well understood.

For example, in the case of gasoline and crude oil from the 80’s one can show that the volatility of prices decreases from the spot market to consumers:

In fact, if we look at the actual electricity prices in Europe across markets since the beginning of the war, it seems that while prices have increased, they weren’t as volatile as the prices in the spot market:

So while we should expect household gas prices to decrease, their volatility in the spot markets will be more pronounced than that of retail prices.

The main conclusion: it’s going to be a volatile winter —weather, gas prices, geopolitics. But building supply chains takes time, so this winter might be milder, and while there may be some temporary relief, it’s never too late to start some long-term planning, building more storage capacity, and diversifying energy sources.

Thought provoking article! Some related thought. Consider the price problem: (p-c) P(V\ge p). If c is a random draw from a distribution C, then one can look at the distribution of P=\argmax_p (p-C) P(V\ge p) driven by the randomness in C. Whether the volatility of C is being amplified or ameliorated in P, is related to the property of distribution V. This problem is also related to whether the passthrough rate p(c) is more than or less than 100%.

1-year forward energy contracts are still being offered at 400-500 euros, while the spot market is in the low 100's (today.) How long do you think the energy producers will hold onto these margins? Particularly while countries in the EU continue to enjoy the profits from their energy tax while pricing is elevated...are they really anxious to fix the solution? Also, the spot energy market is dead because nobody wants to take the risk and the future is clear as mud.

My guess is that once 2023 arrives and there is more parody in industry / energy market (i.e. 2022 1-year contracts will have reached their maturity and consumers will have to renew their contracts) that the entire market will move up and the cost will remain elevated. This IMO puts a strangle hold on EU businesses with being globally competitive.