The Morning Brew title last week was “Cold Storage is so Hot Right now.”

I can’t beat this title.

What’s the story?

“The hottest IPO of the year came from a company best known for its frozen assets. Lineage Logistics, the world’s largest operator of cold storage facilities, raised $4.4 billion in its public listing last Thursday at a valuation of more than $18 billion. It was the largest IPO of 2024, showing that keeping pizza rolls ice-cold from the factory to the freezer aisle is a massive business.”

Not a lot of AI, but one job AI can’t replace.

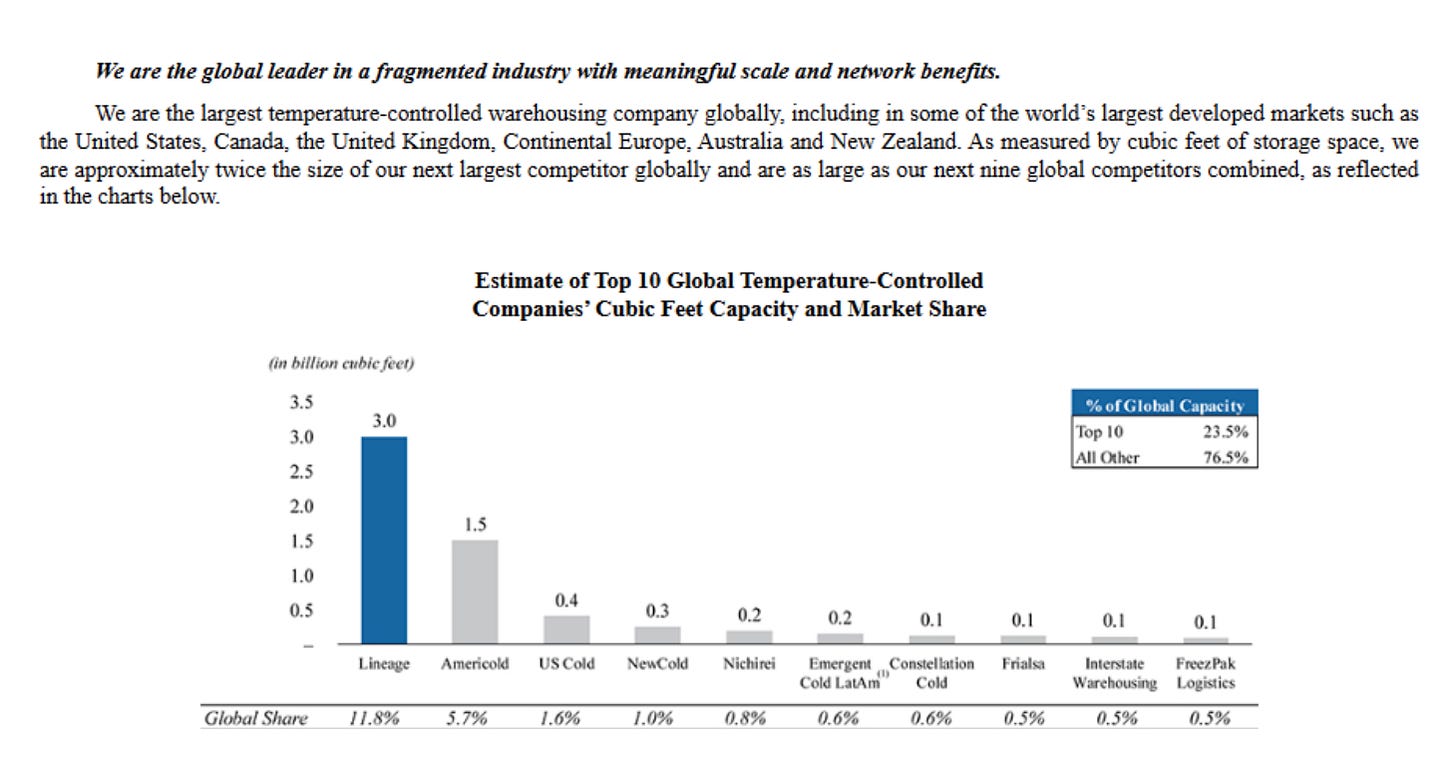

When looking at their S-1 filing, one can find the following:

Very few things perk my ears more than terms like “meaningful scale” and “network benefits.”

So I took a closer look at their S-1 to check:

Well… I can think of many ways to describe this graph, but economies of scale is not one of them.

So let’s delve deeper to better understand what makes the firm that keeps our peaches fresh and our bananas yellow (but not too yellow) operational and scale-wise interesting.

What is the Cold Supply Chain?

The cold supply chain, often referred to as ‘cold chain,’ is a critical component in managing the movement of temperature-sensitive, perishable goods. This includes everything from fresh lobster from Maine to bags of frozen peas and racks of ribs. These goods require precise temperature control from production to final delivery to ensure they remain safe and consumable upon arrival.

Managing a cold supply chain is inherently more complex than a traditional one as it involves numerous challenges:

Temperature Control: Perishable goods must be kept within specific temperature ranges throughout their journey to prevent spoilage.

Logistics and Coordination: Coordinating the efficient loading, unloading, and transportation of perishable goods requires meticulous planning and execution.

High Costs: Maintaining temperature control adds significant costs at every link, from storage facilities to refrigerated transportation.

The WSJ has this nice graph on the Strawberry Fields Forever steps:

The supply chain for food is not structurally more complex than that of consumer electronics, but the product’s perishability and the need to maintain temperature control make managing such a chain significantly more complex and expensive.

The Model

To explore the intricacies of the cold supply chain, I developed a small simulation model to study a retailer managing a cold supply chain. I know it’s not exactly what Lineage does, but it’s the problem they’re trying to solve. This model has two critical aspects: the newsvendor-like problem of perishable products, which deals with inventory management, and the concept of pooling, which assesses the efficiency of central vs. local storage.

My simulation explores an inventory optimization problem for a firm that buys and distributes a perishable product across multiple markets. The firm must decide how much inventory to order to a central hub, and how much to distribute to local markets daily to maximize profit while minimizing costs and losses due to perishability.

I’m not claiming that the numbers are realistic or representative of the reality of such firms, but they should help us assess the complexity and scalability of cold supply chains.

Number of Markets (N): 10

Daily Demand in each market: Mean = 100, Standard Deviation = 50

Perishability Probability (P): 50% per day in the local market. So 50% of the products can remain for the next day and the other need to be discarded. By the end of the week, all products will perish, and I assume that the storage at the central warehouse will be better managed; thus, products will not perish.

Cost per Unit (C): $10

Selling Price (S): $40

Holding Costs: Hub (HH): $0.50 per unit per day and Local Market (HL): $1.00 per unit per day. The difference accounts for the fact that the centralized warehouses are located in cheaper areas and can be automated due to their size.

The firm must make two decisions:

QH: What quantity should be ordered at the hub at the beginning of each week.

QL: The target inventory level at each local market at the start of each day.

The simulation was run with varying QH and QL values to identify the optimal inventory levels that maximize profit.

The results are that the Optimal Inventory Levels:

Hub Order (QH): 6600 units

Local Market Order (QL): 160 units

The firm should maintain a high level of inventory at the hub to buffer against demand volatility and perishability. Local markets require frequent replenishment to meet daily demand without overstocking, which reduces holding costs and perishability losses.

This simple simulation study highlights several important implications for managing cold supply chains:

Balancing Inventory Levels: Firms must strike a balance between having enough inventory to meet demand and minimizing costs associated with holding and perishing. Higher inventory levels at the hub can buffer against demand spikes and supply chain disruptions.

Frequent Replenishment: Regular replenishment of local market inventories is essential to avoid stockouts and excessive perishing, ensuring product availability and customer satisfaction.

Demand Volatility: Increasing demand volatility necessitates higher buffer stocks. Firms should continuously monitor and adjust inventory policies to respond to changing market conditions.

However, today’s goal is not just to study how to optimize such supply chains, but also to discuss their scalability.

Scalability Challenges in Cold Supply Chains

The question is whether firms that run cold supply chains enjoy supply-side Economies of Scale, i.e., cost advantages that a business obtains from its expansion.

I used the same simulation as before to conduct a study of economies of scale in cold supply chains by increasing the number of markets while keeping the demand per market unchanged. For each scenario, I tracked the impact on total costs, total revenues, and total profits. The goal was to understand how increased scale through expanding the number of markets affects the firm’s operational efficiency and profitability.

The results are below:

For different market sizes (10 to 100) there’s a linear increase in total costs and revenues.

My long-time readers know that this is not what I consider scaling. When revenue and costs increase at the same rate, the results are increased profits but no margin expansion. The profit margins, while substantial, do not exhibit economies of scale typically seen in non-perishable supply chains.

What drives this lack of scalability?

High Local Holding Costs: Local holding costs significantly contribute to overall costs due to the necessity of maintaining adequate stock levels to meet daily demand without incurring stockouts.

Consistent Inventory Levels: The average hub and local market inventories also increase linearly, reflecting the need for higher buffer stocks to account for variability in demand and perishing rates.

Cold supply chains must balance between maintaining product quality and minimizing costs. The local nature and high perishability of products impose constraints that limit the scalability of such operations. As a result, while expanding into new markets can increase revenue, the proportional increase in costs makes it challenging to achieve economies of scale.

Efficient inventory management and localized operations are essential to manage these challenges, but they do not eliminate the fundamental scalability limitations inherent to cold supply chains. As the number of markets increases, the logistical complexity and operational costs also rise. Each local market requires dedicated storage facilities and frequent replenishment from the central hub, which contribute to the growing costs.

Economies of Density in Cold Supply Chains

But this is not the only way to scale.

A firm can increase the density within each market, resulting in what I like to call Economies of Density: cost advantages that a firm achieves due to an increased concentration of demand within a particular geographic area.

When demand is dense, firms can optimize their operations by reducing transportation costs (which I don’t model here), improving inventory management, and leveraging local resources more effectively.

To study the economies of density in cold supply chains, I conducted the simulation increasing the demand per market, while keeping the number of markets constant, and I varied the average demand levels from 100 to 200 in increments of 10. For each scenario, I analyzed the impact on total costs, total revenues, and total profits. The volatility of demand remained constant throughout the simulation to model the fact that as the firm achieves better market penetration, its ability to forecast demand in each market should improve, resulting in a lower coefficient of variation.

For each demand level, I optimized the inventory policies at the central hub (QH) and local markets (QL) to minimize costs and maximize profits. The simulation was run over 200 weeks for robustness.

The following table summarizes my key findings:

The results indicate that as demand (per market) increases, the total costs, total revenues, and total profits also increase (it’s difficult to see, but the cost does increase). However, the total profit increases more than the total cost, demonstrating that the firm is achieving economies of density. This is evident from the decreasing cost per unit of revenue generated as demand levels increase:

For a demand level of 100, the cost per unit of revenue is 0.271.

For a demand level of 200, the cost per unit of revenue is 0.193.

These findings have significant implications for firms operating cold supply chains as achieving economies of density can be a strategic advantage. By concentrating demand and optimizing operations within localized areas, firms can manage costs more effectively and enhance profitability, ultimately leading to a more sustainable and efficient supply chain.

Cold Supply Chain Growth: Scale vs Density

The results suggest that firms operating in the cold supply chain can achieve significant cost efficiencies and profitability by focusing on increasing their reach concentration within existing markets rather than expanding to new, geographically dispersed markets. This strategy allows for optimized inventory levels, reduced transportation and holding costs, and enhanced overall profitability. It primarily allows the firm to carry less safety stock at the local level. These safety stocks are extremely wasteful when it comes to perishable products.

So it’s not about economies of scale per se, since it’s not enough just to expand indiscriminately, it’s about the firm scaling by making better use of its existing markets. I’m not sure if this is what Lineage meant when referring to scale advantages and network benefits. There are few advantages in building a broader network, but there are plenty once the network exists.

This is interesting since it’s counter to what we usually see for non-cold supply chains like Amazon’s e-commerce business. But this can also explain why Amazon struggles with groceries. They lack the pooling benefits Amazon has built on for many years.

Lineage’s advantage is scale; the fact that it’s a nationwide firm. As a retailer, you don’t have to deal with the complexity of managing end-to-end delivery, and the firm takes care of both the national and local aspects of the products that require cooling and temperature control.

Lineage’s advantage grows by serving more retailers that already operate in the markets in which it has capacity, but not so much with just the number of markets. Of course, over time, the firm has to expand to new markets, and part of the appeal is the fact that they can distribute in different markets. But this is not where cost benefits are generated.

You may ask why I am nitpicking about the difference between scale and density.

Scale means one more customer … somewhere.

Density means one more customer… here.

The former is easier in terms of sales and marketing.

The latter is easier operationally.

The beauty of many pooled centralized supply chains is that they don’t need density.

Cold supply chains do!

This means that you need more capital to grow since growth is slower in this case.

Conclusion

Lineage Logistics’ IPO illustrates the challenges of scaling supply chains.

It has been quite successful, but some of that stems from the fact that it’s not an easy business to build, since demand for its services is guaranteed to exist forever (I don’t see a future where we give up on fresh produce).

But it’s also an important reminder that not all economies of scale are created equal.

And when a firm tells you they exhibit economies of scale and network benefits… don’t just take their word for it, look at the data.

Super interesting! Out of curiosity, what platform do you use for your simulations?

Hello! really enjoyed reading this. Lineage used to be a customer of ours (we helped them collect fees at the docks). One thing to call out is that Lineage is mostly pure storage, and does not purchase/resell the goods. They are collecting storage fees from third parties and not incurring the cost of perish themselves (unless of course its their fault). However, the demand thesis still holds, regardless of who the demand is from (consumers or third parties)!