This Week’s Focus: A New Brew in Town

Luckin Coffee—the Chinese chain that outpaced Starbucks in China—has landed in New York, opening its first two locations and signaling a bold new expansion. With over 24,000 stores across Asia and a tech-driven, low-cost model built for speed and scale, Luckin is now testing whether its formula can work in the mature and more expensive U.S. market. This week, we look at Luckin’s financials, business model, and competitive edge, and explore how its arrival may push Starbucks to rethink pricing, tech, and store formats. The global coffee competition just got a lot more interesting.

Luckin Coffee—the Chinese coffee chain that famously overtook Starbucks in its home market—has officially landed stateside.

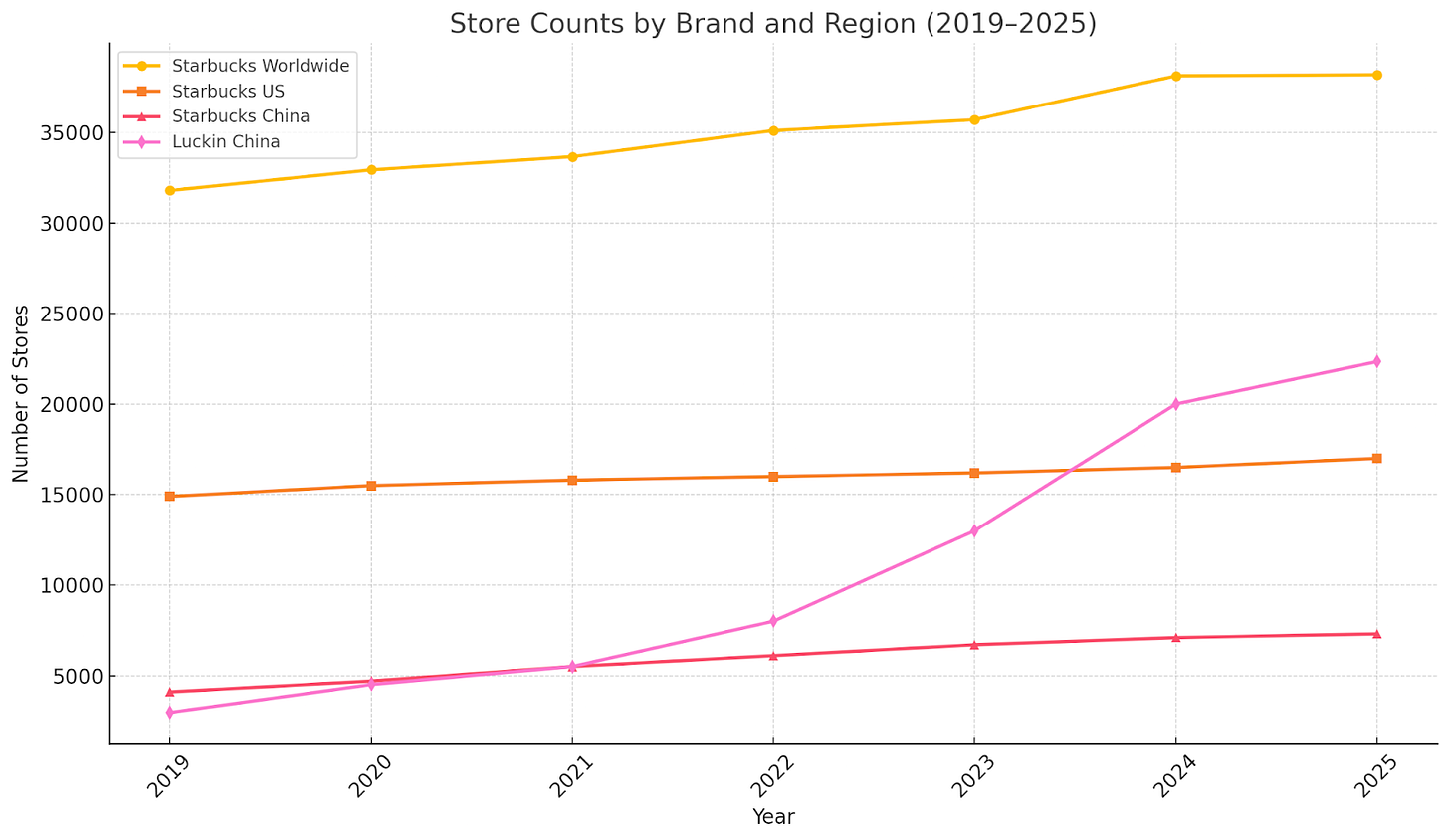

A couple of weeks ago, Luckin opened its first two U.S. stores in New York City, marking a bold challenge to Starbucks on its home turf. The move comes after years of explosive growth in China, where Luckin built a 22,000+ store empire in just about six years, surpassing Starbucks’ China store count by 2019.

Now, with over 24,000 stores across China and other parts of Asia, Luckin is testing whether its formula of tech-driven, low-cost coffee can scale in the mature U.S. coffee market.

In today’s article we take a look at Luckin’s financials and business model—examining its scalability, unit economics, and value proposition—and compare it to Starbucks.

We’ll also explore how Luckin’s cost structure and strategy might shift as it expands into the U.S.

A Rapid Rise in China’s Coffee Market

We like superlatives, but really… Luckin Coffee’s rise has been nothing short of meteoric. Founded in 2017, the company capitalized on China’s nascent coffee culture and rose to the top by opening thousands of small, app-powered outlets at an impressive speed. By Q1 2024, Luckin had 18,590 stores—having added over 2,300 new locations in just that quarter—and its revenue for that quarter reached RMB 6.28 billion (≈$870 million), up 41.5% year-on-year.

For the full year 2023, Luckin’s sales hit 24.9 billion yuan (≈$3.45 billion), an 87% jump from 2022. Notably, in 2023, Luckin’s China revenue eclipsed Starbucks’ China revenue ($3.16 billion) for the first time. This rapid growth reflects a booming Chinese coffee market—one that in outlet count has even overtaken the U.S. as the world’s largest.

One reason Luckin scaled so quickly is China’s huge untapped demand. Historically, coffee has been a luxury or novelty in China, but tastes are changing fast, and per capita consumption, while still low (~11 cups per year in 2022), has been climbing rapidly (up from just a few cups annually in the 2010s).

This pales in comparison to U.S. and European markets where consumers often drink hundreds of cups a year, indicating enormous headroom for growth. Luckin smartly positioned itself to cultivate this emerging habit by offering super-cheap coffee and quirky local flavors that appealed to young consumers. For example, Luckin made headlines with a collaboration to create a Moutai (a famous Chinese liquor) flavored latte—selling 5.42 million cups in a single day when it launched in 2023.

Unlike Starbucks’ upmarket, lounge-oriented approach, Luckin is all about convenience and value. It operates a “100% cashier-less” store model: customers order and pay entirely via Luckin’s mobile app, then simply pick up their drinks in-store or get them delivered. This app-centric system—inspired by ride-hailing apps, according to the company’s founder—maximizes efficiency and keeps labor needs low. Stores are typically small with minimal seating; many are mere pick-up counters or kiosks, a fact that lowers rent and overhead. Such a lean setup has enabled Luckin to price its beverages approximately 30% cheaper than Starbucks in China while still maintaining healthy margins. In short, Luckin built a mass-market coffee brand tailored to China’s price-sensitive, mobile-first customers.

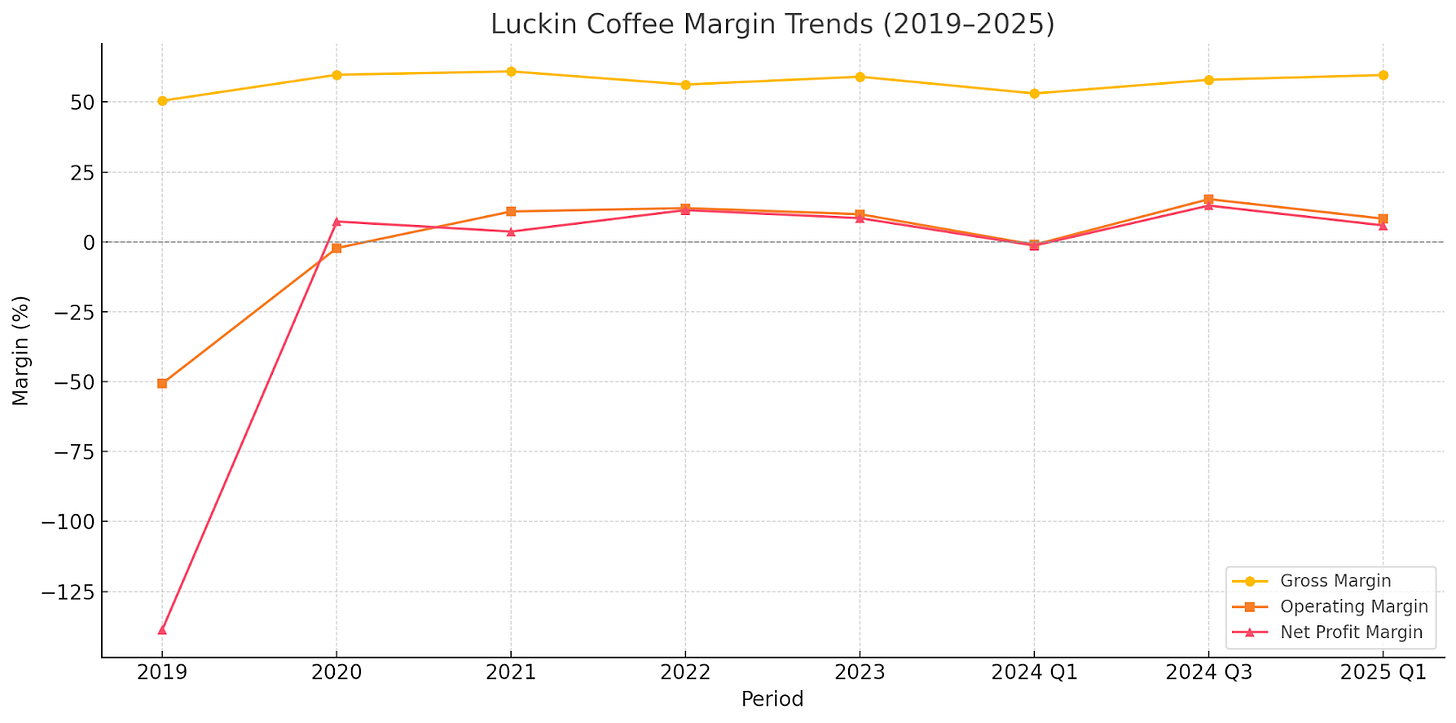

Scalability: Supply-Side Scale and Margin Expansion

Luckin coffee follows a similar pattern of many other food and beverage firms: a potential for scalability, but one that over time translates more into growth rather than scaling. In other words, we see years of margin expansion, but margins remaining (largely) stable over multiple years after that.

On the supply side, its massive scale has initially enabled cost efficiencies. By operating tens of thousands of stores, Luckin can purchase coffee beans, dairy, and other supplies in bulk at lower unit costs. The company has even invested in its own roasting facilities (“green bean” production plants) to vertically integrate and further drive down the cost of goods—a strategy Starbucks also employs. Additionally, Luckin’s centralized app and data-driven operations allow it to optimize inventory and reduce waste across its network. This kind of operational scale advantage contributed to Luckin achieving gross profit margins estimated around 56–60%, which is remarkably high for the industry. High gross margins suggest that once fixed costs are covered, each additional cup sold is quite profitable—a good sign for scalability.

Luckin’s store-level economics have been particularly strong in the past. Before intense competition hit, new Luckin locations reportedly achieved payback on investment in as little as 6–15 months—an astonishingly short period indicating each store quickly became self-sustaining. This was due to a combination of low build-out costs (tiny stores, minimal equipment) and decent sales volumes driven by heavy app promotions. At its peak efficiency, Luckin enjoyed store operating margins above 20% for self-operated stores—meaning the average shop generated healthy profits after covering its direct expenses. These economics allowed Luckin to rapidly reinvest in opening more outlets. In 2023, the chain effectively doubled its store count in one year, a feat that would be impossible without scalable processes and robust unit margins.

What makes Luckin Coffee’s stores so financially appealing is their radically lean, tech-enabled format. Each shop is a compact, no-frills pickup location—typically 20–50 m² (or 200-500 sq ft)—with orders placed entirely through the app. This design keeps startup costs low, with stores costing around $50,000 to build, compared to $700,000 for a typical Starbucks. Despite lower absolute sales, Luckin drives high revenue per square foot and minimizes labor costs by operating with just 1–2 employees per shift. The result is strong store-level profit margins of ~19–20% in 2024. Most stores break even after just 200–250 daily orders, reaching full payback in 12–18 months—well ahead of industry norms.

For comparison, Starbucks takes a different route to strong unit economics, investing heavily upfront to generate higher revenue and profits per store. Its typical U.S. café brings in around $1.5 million annually and delivers a 34% first-year profit margin, or roughly $510,000 in profit—resulting in an impressive 75% return on a $700,000 build-out. That translates to a payback period of about 1.3 years, remarkably close to Luckin’s. The difference? Starbucks wins on volume and premium pricing, while Luckin relies on ultra-low capital costs and operational efficiency to achieve similarly attractive returns. Both models work—but for entirely different reasons.

However, as you can see above, scalability hasn’t come without growing pains. In late 2023, Luckin’s aggressive expansion and a brewing price war with new rival Cotti Coffee—founded by former Luckin executives—began to squeeze margins. To fend off competition, Luckin slashed prices and flooded the market with deals—e.g., RMB 9.9 (≈$1.40) lattes became common with vouchers. These tactics, while boosting traffic, diluted profitability. Luckin’s store operating margin plunged from 25% in Q1 2023 to just 7% in Q1 2024. The company even posted a net loss of RMB 83 million (~$11.5M) in Q1 2024, versus a solid profit the year before. In effect, Luckin traded short-term profits for market share—a classic scalability strategy to cement its dominance, albeit at a cost. Executives acknowledged this “slight dip” in profits, attributing it to intensified competition and macroeconomic fluctuations, while expressing confidence in Luckin’s scale advantages and efficiency for the long run. Indeed, as 2024 progressed and the price war pressure began to ease, Luckin’s margins showed signs of rebounding. By the end of 2024, store-level margins reportedly recovered to ~19–20%, suggesting the company can regain profitability once competition subsides. Nevertheless, margins have been consistently following a downward trend, implying that not all growth is scalable.

Unit Economics and Path to Profitability

As evident from above, despite some volatility, Luckin Coffee appears to have a credible path to sustainable profitability, thanks to fundamentally sound unit economics.

Even during periods of heavy investment and subsidies, most Luckin stores have remained contribution-positive at the unit level. For example, during the worst of the 2023 price war, Luckin still managed a net profit of RMB 290 million in Q4 2023 (~$40M)—admittedly its third-worst quarter in two years, but still in the black. This indicates that the core business model can generate profit even under duress. The company has no meaningful long-term debt and has been free-cash-flow positive, meaning it can fund new store openings from its own cash generation rather than relying on external financing. This self-funding ability is a strong sign of a scalable, healthy business.

A comparison between Luckin Coffee and Starbucks is inevitable, especially since Luckin has been dubbed ‘the chain that beat Starbucks in China.’ Each company’s approach represents a different strategy in the coffee business, with distinct strengths.

Operationally, Starbucks and Luckin Coffee have entirely different playbooks. A typical, busy Starbucks in the U.S. serves around 400–600 customers per day, and some high-volume drive-thrus go even higher. With an average ticket of about $5 and estimated annual revenue of $1.3 million, this suggests ~700 daily transactions—many Starbucks customers buy food or multiple drinks per visit, increasing the average spend. By contrast, Luckin is built for high-frequency, low-ticket transactions—often single beverages priced at $3–4. In China, Luckin stores in dense areas regularly surpass 600 orders per day, and if their U.S. stores can reach even 400 cups a day, that’s $1,200 in daily revenue—well above what many of their Chinese stores generate. Because there’s no café seating or custom drinks, Luckin can maintain faster throughput, potentially driving higher sales per square foot than Starbucks despite a lower ticket size.

This contrast plays out across multiple operational dimensions. Starbucks maximizes revenue per customer with premium pricing, customized options, and food pairings—pushing the average ticket to $7–8. Luckin is currently focused on speed and simplicity, which keeps its average ticket closer to $3–4. While U.S. Starbucks stores have historically achieved 25%+ store-level profit margins, Luckin’s U.S. margins may be lower until it scales (perhaps in the 15–20% range). At the corporate level, Starbucks runs a lean North American business with 18–20% operating margins, while Luckin is still building toward high-single digits in China. The key difference is that Luckin can profitably operate numerous smaller-format stores, each generating $50k/year in profit (versus Starbucks’ $200k+), and do so with half the staff. That’s possible because Starbucks deliberately builds in slack—offering comfortable seating and a slower in-store experience—while Luckin maximizes staff efficiency with an app-based model and minimal human interaction.

One way to assess the quality of Luckin’s business is to look at its return on invested capital (ROIC)—how efficiently it turns invested money into profit.

While Luckin’s exact ROIC is hard to calculate during its hyper-growth phase (due to the accounting turmoil from its 2020 fraud scandal and rapid changes in capital structure), the components driving ROIC are evident.

ROIC is driven by profit margins and capital turnover. Luckin’s strategy optimizes both: it aims for respectable profit margins per store (through low costs and high volume) and it employs relatively small amounts of capital per store, allowing quick expansion and fast payback. For instance, a Luckin kiosk might cost a fraction of what Starbucks spends to build a spacious café, yet that Luckin kiosk generates higher sales throughput. This means each dollar Luckin invests in new stores can yield a high amount of revenue (high asset turnover) and, with growing margins, a solid operating profit. In contrast, Starbucks invests significantly in ambiance, larger real estate, and trained baristas for each location—which yields a premium experience and pricing, but also a heavier capital and expense load.

Starbucks’ ROIC in recent years has been around 10–12%, reflecting a mature, moderately efficient use of capital. Luckin’s ROIC has likely been lower than that during its early ramp (given it was incurring losses until 2022-2023), but its incremental ROIC on new stores is quite high—evidenced by the short payback periods and strong store margins when not in a price war. As Luckin’s growth moderates and it focuses on harvesting profits from its vast network, its ROIC could rise substantially, potentially surpassing legacy peers. In investor circles, some have argued Luckin stock is undervalued precisely because of this combination of high growth and improving returns. For example, based on mid-2025 share prices, Luckin was trading around 20 times trailing earnings—a lower P/E multiple than Starbucks or other coffee competitors despite its faster growth. This suggests the market is still assigning a risk discount (likely due to Luckin’s past accounting scandal and China-specific uncertainties), but it also highlights the upside if Luckin’s growth translates into enduring profits.

Of course, the path to profitability hasn’t been linear. The 2020 accounting scandal was a major derailment—Luckin was found to have fabricated revenue, leading to a delisting from Nasdaq and a $180 million fraud penalty in 2020. The company underwent Chapter 15 bankruptcy restructuring in 2022 to resolve its debts, and it wiped out the old management team. Under new leadership (backed by private equity firm Centurium Capital and others), Luckin essentially rebooted with more rigorous financial controls.

Since then, it has regained investor confidence by delivering real growth and publishing audited financials showing the huge revenue and sales gains discussed. The scandal era reminds us that hyper-growth companies can implode if governance and internal controls don’t keep up. However, Luckin’s successful turnaround—achieving GAAP operating profits and positive cash flow by 2023—suggests its business model is inherently profitable when executed honestly. Now the main questions are operational (can it fend off competition and maintain growth?) rather than existential.

Adapting to the U.S. Market: New Costs and Considerations

Now, as Luckin enters the United States, it faces a very different market dynamic. The U.S. is a highly mature coffee market with entrenched habits and competition on every corner—not just from Starbucks (which has 17,000+ U.S. locations), but also Dunkin’, Tim Hortons (in some regions), countless local cafes, and even McDonald’s and convenience stores selling cheap coffee.

Several factors will challenge—and potentially change—Luckin’s cost structure and value proposition in the U.S.:

Higher Operating Costs: One immediate change is labor and rent costs. In China, Luckin benefited from relatively low wages for service staff and cheaper rents (especially for the small-footprint stores it favors). In the U.S., wages for baristas and shift leads will be significantly higher due to minimum wage laws and overall labor market differences. Rent in Manhattan (where Luckin’s first U.S. stores are) is among the most expensive in the world. Even for a tiny East Village storefront, fixed costs will be steep compared to a similar store in Chengdu or Wuhan. This erodes Luckin’s ability to dramatically undercut on price while still making money. In fact, early signs show Luckin is not drastically cheaper than Starbucks in New York. A 16-ounce brewed coffee at Luckin’s NYC location costs $3.45 versus $3.65 at Starbucks—virtually the same. Some Luckin items are even pricier than Starbucks (their iced matcha latte is $6.45 vs $6.25 at Starbucks). These price points suggest that Luckin has adjusted its value proposition: it’s not positioning as a deep discounter in the U.S. (at least initially), likely because it doesn’t have the cost advantage to do so yet. Instead, Luckin may compete more on novelty and convenience in the U.S. rather than just price.

Supply Chain and Scale (or Lack Thereof): In China, Luckin’s massive scale gives it bargaining power with suppliers and efficiency in distribution. In the U.S., as a newcomer with just two stores (for now), it has none of those advantages. Sourcing coffee beans, dairy, and other ingredients at a competitive cost will be harder without scale. By contrast, Starbucks has an integrated supply chain—roasting plants, warehouses, and contracts—built over decades in the U.S. It will take time (and investment) for Luckin to establish supply chain infrastructure or partnerships stateside that resemble the efficiency it has in China. We might expect Luckin’s U.S. operations to run at a loss until it reaches a higher store count to spread those fixed supply chain costs. The company’s recently posted job listings indicate it’s setting up a U.S. headquarters in New Jersey to build out these capabilities. Until scale is achieved, Luckin might not be able to rely on low unit costs as a competitive edge in the U.S.

Consumer Awareness and Brand Perception: In China, everyone in major cities now knows Luckin; in the U.S., it’s an unknown brand. That means Luckin will have to spend on marketing to build awareness and trial. Its initial marketing has leaned on playful social media—posting on Instagram “You’re luckin now” to announce the NYC opening—and offering promotions during its soft launch. It’s a start, but winning over U.S. consumers will require more. The value proposition might need tweaking: Americans already have convenient coffee (drive-thrus, mobile order at Starbucks, etc.) and cheap coffee (McDonald’s, gas stations). Where does Luckin fit? Possibly, Luckin will pitch itself as tech-forward and trend-setting, introducing unique drink flavors that intrigue curious New Yorkers. If it sounds familiar, you’re not wrong.

It can leverage the authenticity of being a huge Chinese brand—for instance, featuring popular items that were a hit in China (like fruit-blended coffees or coconut lattes) as a differentiator. If successful, Luckin could carve a niche among younger consumers looking for something different from the usual Starbucks menu. But if the product doesn’t stand out, Luckin might struggle to draw people away from their habitual coffee choices, especially without a significant price advantage.

Regulatory and Cultural Differences: The U.S. café culture includes a strong expectation of personalization and service. While many Americans happily use mobile apps for speed, many also enjoy chatting with a barista or customizing orders in-store. Luckin’s no-cashier model may need to accommodate those expectations (perhaps by having staff available for assistance or to handle cash for those who want it). Additionally, issues like tipping (virtually nonexistent in Chinese fast coffee shops) could come into play—will Luckin’s staff accept tips or will the fully app-based payment flow bypass that? If the latter, Luckin might have an edge as some customers prefer a no-tip, no-frills transaction. Culturally, Starbucks has cultivated an image of the “third place” in the U.S.—a cozy spot between home and work. Luckin’s utilitarian model lacks that ambiance, so it targets a different use-case (purely grab-and-go). It remains to be seen if that use-case is already saturated by other players in the U.S. (like Dunkin’ Donuts, which similarly offers quick, cheaper coffee without the artisanal vibe).

Cost Structure Adjustments: Given all the above, we anticipate Luckin’s U.S. cost structure will have higher labor and occupancy costs per store, higher cost of goods (initially), and likely higher customer acquisition costs (marketing) than in China. To compensate, Luckin might operate U.S. stores with even leaner staffing (relying on the app to do most of the work and only a minimal crew to make drinks). It might also focus on high-traffic, small-footprint locations (the first two NYC shops are in busy Manhattan areas) to maximize volume per square foot. In time, if Luckin scales to hundreds of U.S. outlets, it could regain some supply-side efficiencies (bulk purchasing, maybe even roasting beans locally) which would improve its cost structure. But until then, Luckin’s expansion to the U.S. might be more about strategic presence rather than immediate profitability, and embrace slimmer margins or even small losses as the “cost of entry” into the world’s most competitive coffee market.

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) Outlook in the U.S.: One interesting consideration is how Luckin’s ROIC might fare as it expands in the U.S. In China, as discussed, the ROIC on new stores was very attractive due to low investment per store and growing profits. In the U.S., the investment per store will be higher (due to construction permits and higher costs in equipment and rent), and the profit per store will likely be lower at first. This could reduce Luckin’s overall ROIC in the short term. Essentially, the company is deploying capital into a market with lower immediate returns, hoping that long-term it pays off through international diversification and growth. For comparison, Starbucks has high store-level ROIC in the U.S. because its brand allows premium pricing and its scale here is unparalleled. Luckin must prove it can achieve a solid ROIC in the U.S. by either driving high volume through each store or by eventually differentiating enough to maybe charge a bit more without losing customers. If it simply competes on price with Starbucks in the U.S., its ROIC will be under pressure. However, if Luckin can import some of its innovative flair by introducing novel beverages that Starbucks doesn’t have, it might find a profitable niche that yields decent returns. Given Starbucks’ 50-year head start, Luckin’s U.S. expansion will likely be cautious. It’s telling that they started with just two stores and are feeling out the market. Each new store’s performance will teach them about American consumers’ response to the model.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead for Luckin Coffee

Luckin Coffee’s rise has been full of drama—rapid growth, a major scandal, and a strong comeback driven by tech-enabled efficiency and value pricing. It has shown it can outscale even Starbucks in China by offering a disruptive, low-cost model built for speed and volume. Now, as it enters the U.S., Luckin brings agility and innovation, but faces new challenges like brand recognition and higher costs.

In turn, Starbucks is being pushed to evolve. Luckin’s presence may force it to rethink store formats, tech adoption, and pricing strategies. The competition could benefit consumers on both sides of the Pacific.

Could the company eventually pose the biggest threat to Starbucks since someone figured out how to make pumpkin spice at home?

Time (and many cups of bad coffee) will tell.

Luckin’s entry into the U.S. underscores a broader question about whether the ‘third place’ model that is central to Starbucks’ identity is still the dominant value proposition in a post-COVID, app-driven world. Starbucks has long monetized ambiance and personalization but Luckin monetizes efficiency and habit.

I live in Shanghai and I've witnessed Luckin's growth since 2018, and it seems incredibly genius. Their business model is definitely their strongest selling point. I remember hearing groups of parents getting together and purchasing Luckin because of their cheap discount group-buy deals back in 2018/2019. Now, even after the scandal in 2020, Luckin's presence is even stronger than before. My classmates (and my dad) order Luckin frequently due to the low prices and convenient pickup--many stores are small but easy to find--and it helps that there's a Luckin shop basically 10 minutes from anywhere in Shanghai. Nice article!