Last week, Business Insider published an interesting article about a leaked memo that Walmart sent its regional and store managers allowing them to either fully or partially shut down its automatic inventory management system (called ISA):

“‘We have heard your concerns around the ISA tiering system,’ and regional general managers ‘will now be able to submit changes,’ the memo said. Depending on how overloaded their stores are, these managers can decide to keep ISA on, turn ISA off for general merchandise but keep it on for food and consumables, or turn off ISA completely. The memo also outlined various inventory processes stores should complete before opting to turn off ISA.”

Walmart finished last quarter with a 32% increase in inventory but only a slight rise in sales. This, of course, is not unique to Walmart, as we have mentioned before.

But I am sure people are trying to figure out what to do within every firm. Amazon is launching an aggressive attempt to sell inventory on its Prime Day sales, Target is trying to liquidate its inventory, and Walmart is blaming its employees:

“‘We are being blamed for poor processes when it's actually a flawed system,’ the Florida employee said. ‘Stores basically have no chance.’”

The photos published by Business Insider show stores having run out of room for their inventory, and having to use the store’s floor as storage space, placing pallets with packaged products in aisles, making them almost unwalkable and blocking access to private breastfeeding rooms and bathrooms.

Walmart is blaming its employees, and the employees are blaming the algorithms.

“‘The system will automatically zero out the counts for anything it hasn’t ‘seen’ in a few days,’ a store manager from Texas who has been with Walmart for over a decade said. ‘So if something doesn't make it out to the shelf in 24-48 hours, the system will zero it out, then the ordering system will see we’re out and then order more merchandise. It's a vicious cycle.’”

The inventory glut is something that I have written about in the past. Still, as we know, this wasn’t unexpected given the volatility of demand during COVID and the upcoming recession. It’s hard to blame humans or algorithms for ordering more than anticipated at a time where people were buying more than expected (whether online or in person), and supply chains were facing issues. And regardless of who was or is to blame, now we must all face the consequences.

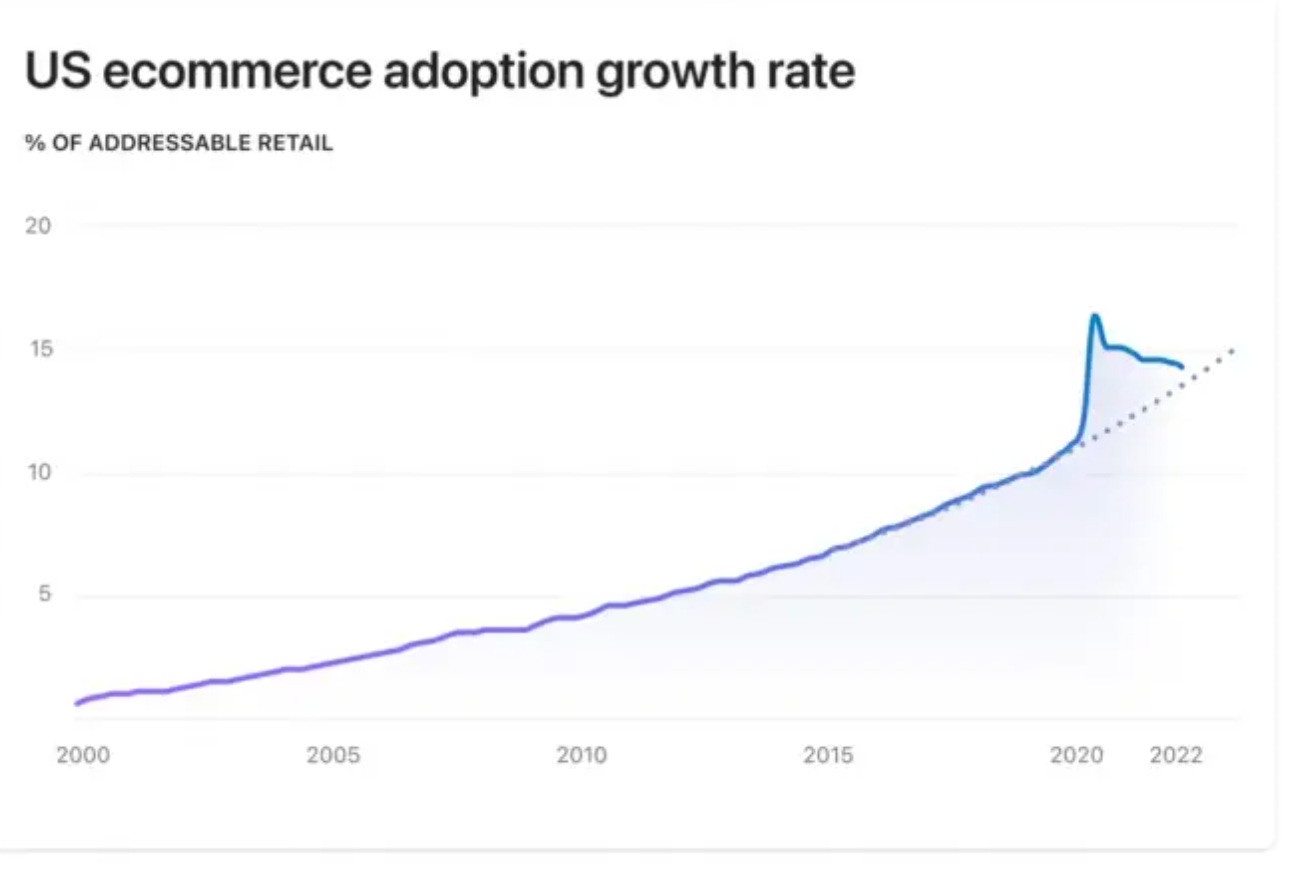

This is, of course, somewhat related to this week’s announcement by Tobi Lütke, founder and CEO of Shopify, stating that they need to lay off 10% of employees since the firm found itself on the wrong side of the bet that e-commerce would be reaching new levels of growth.

As you can see in the following graph, this is not the case. But what we can clearly see now, was not visible at the peak of the growth chart in 2020, when decisions had to be made.

In the case of Shopify, it was a human-made decision, although it may have been better if it was an algorithm. In the case of Walmart, the employees are blaming the algorithm, which indeed seems to be creating at least some of the problems.

The tension between humans and algorithms in the context of operational decisions is quite high, and will only persist and become more extreme in the short and long term.

Humans tend to believe that they are better than algorithms at making decisions. We tend to think that situations, such as staffing decisions for example, are too complex to be modeled, and need too much critical thinking for an algorithm to be able to choose.

But why not? Why can’t we build an algorithm that will consider everything: the state of the economy, the workload (we can connect it to Salesforce and Jira)? And have it make better decisions than humans? After all, humans seem to be too optimistic about the future (or not optimistic enough), and the truth is, we’re not that great at understanding probability. So, why not let an algorithm make these decisions?!

But on a more serious tone, the situation with inventory is a bit more subtle.

First, these are tactical and usually reversible decisions that need to be made very frequently and can be simplified to something where an algorithm can actually dominate a human. In particular, inventory theory is quite robust and has been tested for quite some time, so we can truly trust algorithms to make decisions in this case.

But the word trust is crucial here.

In particular, I think there are two critical questions:

When should managers trust the algorithm more than humans, and are there situations in which you want employees’ judgment to be able to override algorithms?

When will employees finally trust algorithms?

When do Humans Dominate?

So let’s start with the first question,

I’m going to state the obvious, but algorithms have a hard time predicting things that they have never seen before. For example, we use the term stagflation, but there has only been one stagflation in the US economy, in the 1970s. No algorithm can predict another based on a single observation.

Over the last few months, I was involved in a project, helping a fast-growing firm predict their demand (not a firm I have invested in, so don’t try to infer anything from this). After trying the most advanced machine learning algorithms and time series analyses, the best model was one of exponential smoothing. What does this tell us? When the world is chaotic, simple and robust models work better than even the most sophisticated ones.

This is not to indicate that people would necessarily do a better job. But (anecdotally) it shows that algorithms are not always the solution. But you may say that this is a situation with extreme volatility, where we expect humans to do better. What about in a more “normal” situation?

A few years ago, I co-authored a paper in collaboration with a firm from the food and beverage sector (which I can’t disclose). The question was whether an algorithm of demand forecasting could be improved when retailers, deeper in the supply chain, share information about how much inventory they have in their warehouses. The theory predicted that this information would not be helpful since it’s essentially what the firm itself had shipped.

But to our surprise, it was quite helpful, because the employees that were supposed to execute a very simple inventory strategy, constant days of inventory, in reality, actually took two additional actions to “correct” the algorithm: production smoothing and full truck loads. For example, when an employee is expecting a ramp-up of demand due to an upcoming event or extreme weather, they may want to try to smooth the production, and they do so by correcting the forecast upwards.

Both of these actions are meant to improve efficiency. When talking with people at the firm, it was clear that the managers did not want to disallow these actions. Primarily, because they wanted employees to feel somewhat empowered (that they’re not just following an algorithm), but more importantly, because employees may have local knowledge about the weather or events (e.g., festivals) that the algorithm cannot incorporate. Disallowing these actions will not allow the firm to ever fully incorporate information that the algorithms don’t take into account.

In fact, we can all agree that people are better at incorporating changes, mostly big ones, as well as massive uncertainties.

The implication, however, was that due to these “corrective actions” the firm ended up with more inventory than necessary than if it had religiously followed its strategy. So there is a cost to allowing employees to meddle with the algorithms.

When Do Humans Trust Algorithms?

So the question becomes: How do you get employees to trust an algorithm on most days and maintain their ability to intervene only in extreme situations? This is essentially what pilots do: They trust the autopilot for most of the flight, but not for departures and landings (where the situation changes regularly), or under extreme weather. Can we get the same idea going for operational systems?

This has been the research of several of my colleagues.

“Although evidence-based algorithms consistently outperform human forecasters, people often fail to use them after learning that they are imperfect, a phenomenon known as algorithm aversion. In this paper, we present three studies investigating how to reduce algorithm aversion. In incentivized forecasting tasks, participants chose between using their own forecasts or those of an algorithm that was built by experts. Participants were considerably more likely to choose to use an imperfect algorithm when they could modify its forecasts, and they performed better as a result.”

So the key is the ability to modify.

In the supply chain world, this ability is going to create significant friction over the next few years since supply chains are becoming more complex, and with them, the algorithms. In fact, deep learning algorithms’ decisions are hard to interpret, making it even harder to incorporate humans in the process.

Readers of this newsletter know that I believe volatility will only increase, and I don’t only mean demand volatility. Supply disruptions are going to be almost as common. And while we know that people are not great at dealing with volatility, I would argue that the type of volatility we’ll see over the next few years will be such that even algorithms will be worse at dealing with.

So maybe our approach to algorithms should be one similar to that of flight autopilots: Co-existence that builds trust, rather than one that tries to cancel each other out, Walmart-style.

Totally agree with the collaboration of algorithm and human can bring the most benefits. However, do you think that once the algorithm is strong enough, like it has the database of extreme situations like festivals and will adjust automatically to it. Do we still need people to intervene or supervise algorithm?

Providing model explainability/interpretability should also help reduce model aversion since the humans can see the top drivers for a given recommendation. Such increased transparency can also allow humans to provide targeted feedback on model performance.