Manhattan’s Congestion Pricing: Efficiency and Fairness

On Thursday, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority of New York (MTA) held the first out of 6 hearings regarding their plan to institute congestion pricing in Manhattan.

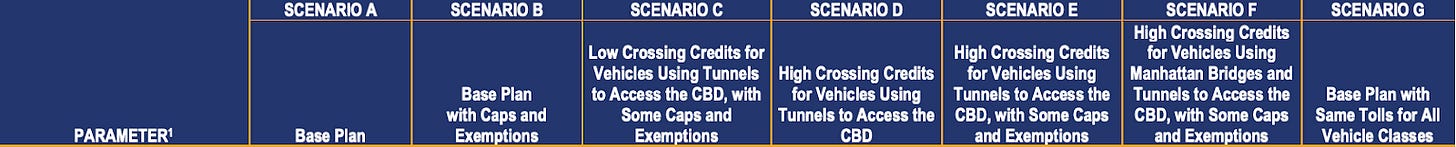

The plan contains many options and scenarios, as outlined below:

But as you can see, charges for entering the Central Business District of Manhattan (which is defined as the area below 60th Str. and above The Battery) will start at $9 (peak time) and $7 (off peak), and might go all the way up to $23.

If you’re wondering when peak time is...

…well it’s basically all day.

And this is actually not surprising. If you look at the pattern of cars entering and leaving this area throughout the day, it’s clear that traffic intensity remains stable.

But note that the “stability” (or lack of sensitivity to real congestion) of this pricing makes it less of a congestion pricing system and more about taxing those entering this area with vehicles. What’s the goal of this new initiative?

The Gothamist reported:

“The aim of congestion pricing is to discourage driving into Manhattan, while also raising $1 billion a year through tolls to fund improvements to mass transit. About 80% of the money raised would go toward subways and buses, with 10% to the Long Island Rail Road and 10% to Metro-North. The current capital plan stands at up to $56 billion, and revenue from the proposed congestion pricing plan would cover 30% of it. The MTA hopes to invest the $1 billion and generate $15 billion in total.”

As expected, the first hearing was quite contentious.

“Across almost seven hours Thursday night, the speeches grew in volume and intensity — a cacophony of New Yorkers brought together over Zoom to either praise or denounce one of the most contentious transportation projects.”

You can still catch up on the final few hearings, today (the day this is released, from 1pm ET) and over the next few days.

The study done by the team proposing the plan is very comprehensive, but I think it’s useful to think more broadly about congestion pricing and its role, before revisiting Manhattan’s case.

Congestion Pricing: The Upside

The reality is simple. We live in a world where resources are scarce. Imagine any resource: a short-cut to your work, a city everyone wants to access, an instructor everyone wants to take a course with. The same way we want these resources, others do too.

These resources, that are basically “service systems,” can be divided into two types: those where the lack of capacity means that some users don’t have access to the service (access to a course, or a flight), and those where the lack of capacity means that the service becomes slower or users experience delays. Roads and transportation systems that are road-dependent (e.g., cars, buses, and taxis) are of the latter type.

In the most seminal research paper at the interface of queueing theory and economics, P. Naor shows that:

In a system where each individual decides whether to join the queue (of that scarce resource) or not, and in which there is value obtained from getting the service, but also a cost for waiting in line (a cost proportional to the time you spend waiting, which you can think of as the opportunity cost of spending time in traffic rather than at home reading this newsletter or watching the author’s official favorite French movie, Jules et Jim), people tend to join a more congested system than the one prescribed by a “social planner.”

First, what does this mean? And second, why?

A social planner may be someone who knows all costs of all people, and the value obtained from the service, and decides how to ensure optimal welfare is achieved. It sounds very theoretical, but this is the most “efficient” use of this system.

The paper shows that when individuals make their own decisions, they opt for a more congested system than the one prescribed by this social planner.

Why? The main result in the paper is that people do not internalize their externalities on others. And this is, I think, a unique feature of these congestion-based service systems:

Your decisions impact others in a non-linear manner. I am sure you remember this graph from your queueing theory class in the 3rd grade:

Your decisions almost always impact others when resources are scarce, but even more so in congestion-based systems, since the more congested the system you join, the larger the impact on others (higher utilization leads to a higher marginal impact on every customer).

The solution?

You guessed it. Pricing! Congestion pricing!

Broadly speaking, the idea is to charge people for their externalities on others.

This brings me to another seminal research paper by Mendelson and Whang.

This paper resembles the congestion pricing situation in NY even more, since it basically talks about a situation in which people have multiple options: to either use public transportation or drive to the city. Their idea is to charge people for their externalities on others, so the people who either have high value from using the resource or have a high cost of waiting time, will get priority on the resource (in our case, access to Manhattan).

So overall, the theory is all in favor of using congestion pricing as an idea.

The decision-making agent must understand that there are tradeoffs, and when the pricing is done correctly, it can be a win-win situation. Win for those who have a high cost of waiting (since it reduces the congestion for them at a price of course), and win for those who have a lower cost of waiting (since they still get access to the city) but now will have better infrastructure, as the money raised through the congestion pricing will be invested in these alternative options (the subway and LIRR), as well as the environment (since there will be fewer cars in Manhattan).

And indeed, this is exactly what the MTA says:

“‘This is different than a typical tolling system,’ a senior MTA official who briefed reporters on the document ahead of its public release said. ‘[In a] typical tolling system you’re tolling for upkeep of the facilities. In this case we’re really tolling to help reduce congestion and then raise the revenue for transit, which further reduces congestion.’”

Congestion Pricing: The Implementation

New York is not the first place to offer congestion pricing. Singapore, London, and Stockholm have done it before, and as the table created by the MTA task force summarizes below:

In most of these cases, the implementation is very much in line with the one suggested in Manhattan, with a slight variation.

A more interesting case is Israel’s express lane.

“The toll for each trip will be measured on a sliding scale that starts at NIS 7 and rises with the amount of traffic congestion to NIS 75. From simulations, officials expect the average toll to stay well below the maximum, costing about NIS 20-30 during rush hour. Updated prices will be displayed on signs at the entrance to the road from Routes 1 and 412. Speed in the fast lane is expected to average 70 kilometers per hour and 2,000 vehicles are expected to use the road per hour.”

Two interesting observations on this implementation. First, there are more queueing theorists in Israel per capita than in any other country (I am not sure if this is true, but both Naor and Mandelson are Israelis ... and so am I). I guess we really hate standing in line, so it was just a matter of time before congestion pricing was instituted in Israel.

But the Israeli system is interesting in the sense that it’s truly congestion-dependent. You pay based on the congestion at that point in time. But it's hard to plan accordingly. On any day, congestion may be low or high, which requires users to decide in real-time rather than offer fixed prices.

On the flip side, the flexibility doesn’t feel like a constant addition to the existing tolls.

Congestion Pricing: The Downside

But despite all the advantages, there are clearly many issues to address.

Michael Munger and Russ Roberts, both on the libertarian side of the economic theory spectrum, criticize congestion pricing as an improper market solution because, unlike a real marketplace in which an exchange happens only if both sides are better off because of the exchange (the Coasian idea of a market), with congestion pricing, both the person that pays (and has fast access to Manhattan) and the person that doesn’t pay (and thus has to wait longer in traffic, or use a more inconvenient form of transportation) might not be better off.

Both are better off compared to the situation in which they make the alternative decision.

But both may be worse off compared to the situation in which the system (and thus the exchange) is not offered.

For example, imagine that the congestion price is too low, or that the public transportation options are just not good enough based on where people live and work and everyone is willing to pay the entry fee into Manhattan. In that case, no one is benefiting from the system since they are all paying, and Manhattan remains equally congested.

So rather than congestion pricing, it seems more like a “punishment” on everyone commuting from NJ, Brooklyn, and Long Island.

If people do not have much choice on when or how to travel (limited public transportation options, and limited road options), we end up with a solution that is not only unfair, but probably not economically efficient.

One also has to be very optimistic to think that the money gained from this initiative will be invested in the MTA efficiently. From overtime fraud:

“In 2018, Caputo was allegedly paid about $461,000 by the MTA. Of that amount, about $344,000 was paid for overtime he was allegedly [made] to work, according to his complaint. Caputo claimed to have worked about 3,864 overtime hours, on top of 1,682 regular hours, according to the complaint filed against him. That alleged amount of overtime would average out to about 10 hours of overtime every single day of the year, including weekends and holidays, on top of his 40-hour work week.”

Or just simple obstruction of justice.

So while the theory is in favor of congestion pricing, we have to acknowledge that it’s not perfect, and getting the pricing right is actually quite critical.

Finally, there is a question of whether we want to monetize everything. Michael Sandel wrote about that in his book What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. People that don’t like priority access in airports, seem to like congestion pricing, since in this case, it’s about using the funds to improve infrastructure and improve the environment. But you have to pick sides.

To summarize, one can make the point that time (experienced as delay) is already a price we pay and demonstrates our interest in this scarce resource. Congestion pricing results in a solution that may seem fair, but not always economically efficient when the alternatives are bad or the pricing is not reasonable. However, if done correctly, it can be a good enough solution.

Not fair.

Not (always) efficient.

But better than the current situation.

Personally, I hate driving, but I love Manhattan. And while I like the subway for North-South rides on the 2 and 3, I don’t like the East-West options. Whenever I visit Manhattan I am willing to pay more for Amtrak, just so I can read (and write), while on the train, and several of my articles have been written on the train to Manhattan.

I would be willing to pay more to avoid driving, as long as the money is truly invested in infrastructure and only Ubers and taxis are allowed in the city. This would truly be a win-win-win (the third one is me).