Recent weeks have seen a surge in coverage by numerous news outlets, highlighting a wave of substantial investments aimed at building new manufacturing plants across the United States.

The future of manufacturing in the US poses some interesting questions. In particular, will we indeed see an uptick in our manufacturing output, and more importantly, does this mean jobs in manufacturing will make a comeback? If they do, it’s worth asking whether these jobs offer attractive pay, especially when more Gen Zers question the value of a traditional university degree. Could a career in manufacturing be a compelling alternative for them?

Manufacturing Output vs Manufacturing Jobs

For a long time, the common belief was that manufacturing jobs in the United States were a relic of the past, never to return in significant numbers. Serious journalists were saying, “Manufacturing Jobs Are Never Coming Back.”

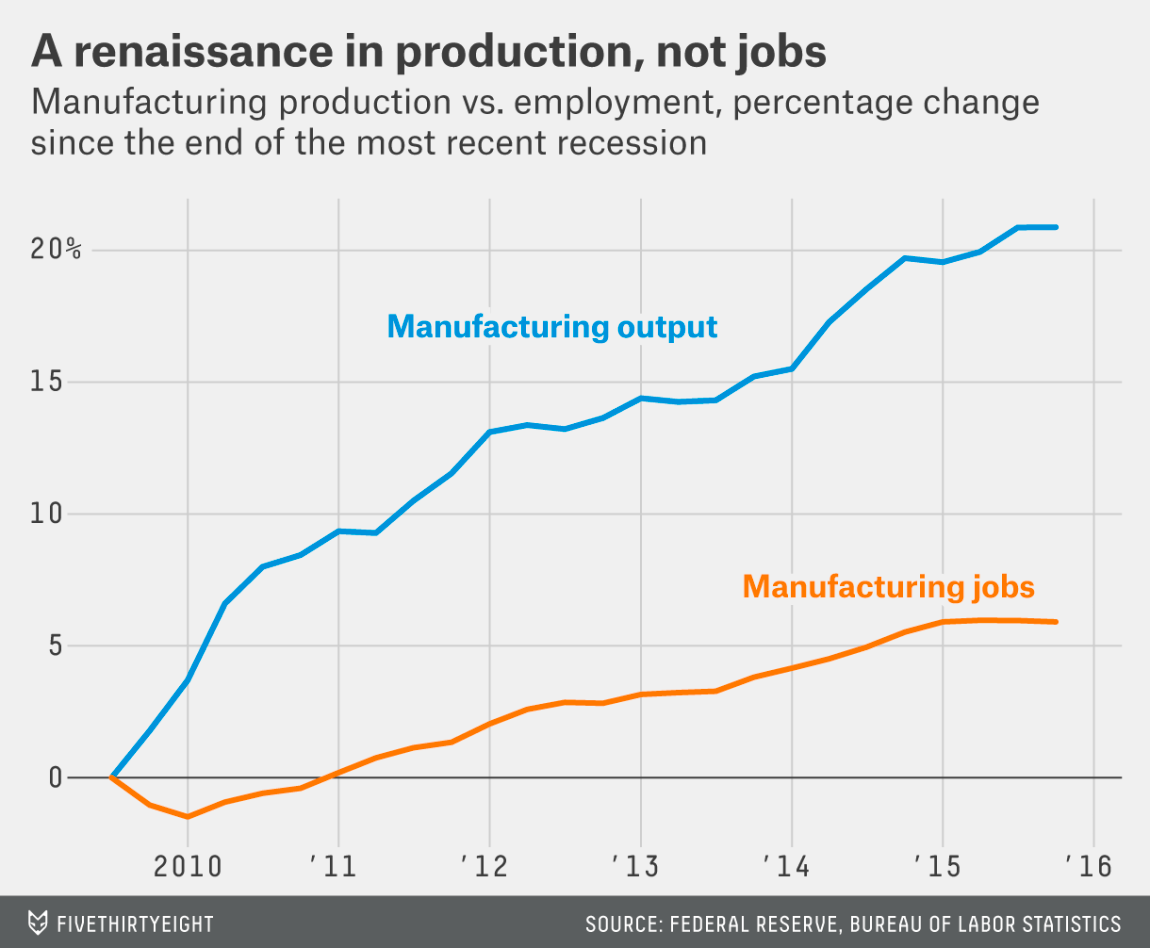

The period from 2010 to 2020 strengthened these expectations, showcasing a notable increase in manufacturing output. Despite this rise, the expected parallel increase in manufacturing jobs did not materialize:

After the 2008 recession, the manufacturing sector saw a significant increase in productivity, as the graph below shows. This improvement was mainly due to advancements in automation and overall efficiency gains, which meant that increased output did not necessarily require a proportional increase in job creation.

Additionally, the nature of the industries and the types of products that experienced a resurgence played a role. Many of these were less labor-intensive by design, possibly due to technological advancements or the shifting focus toward industries requiring less manual labor.

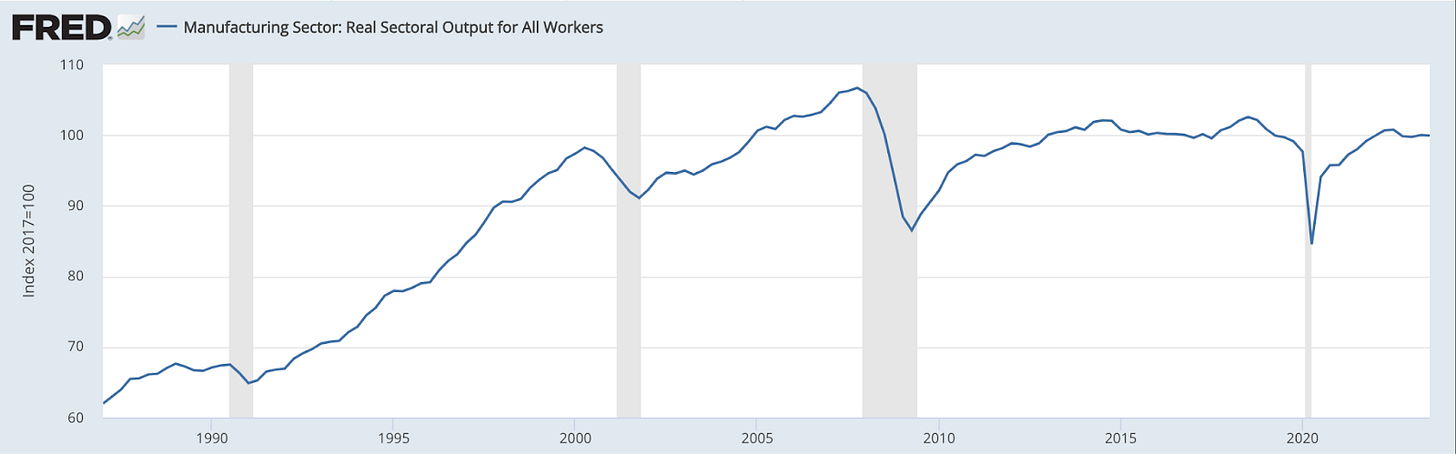

However, these productivity gains stagnated, as shown in the graph below.

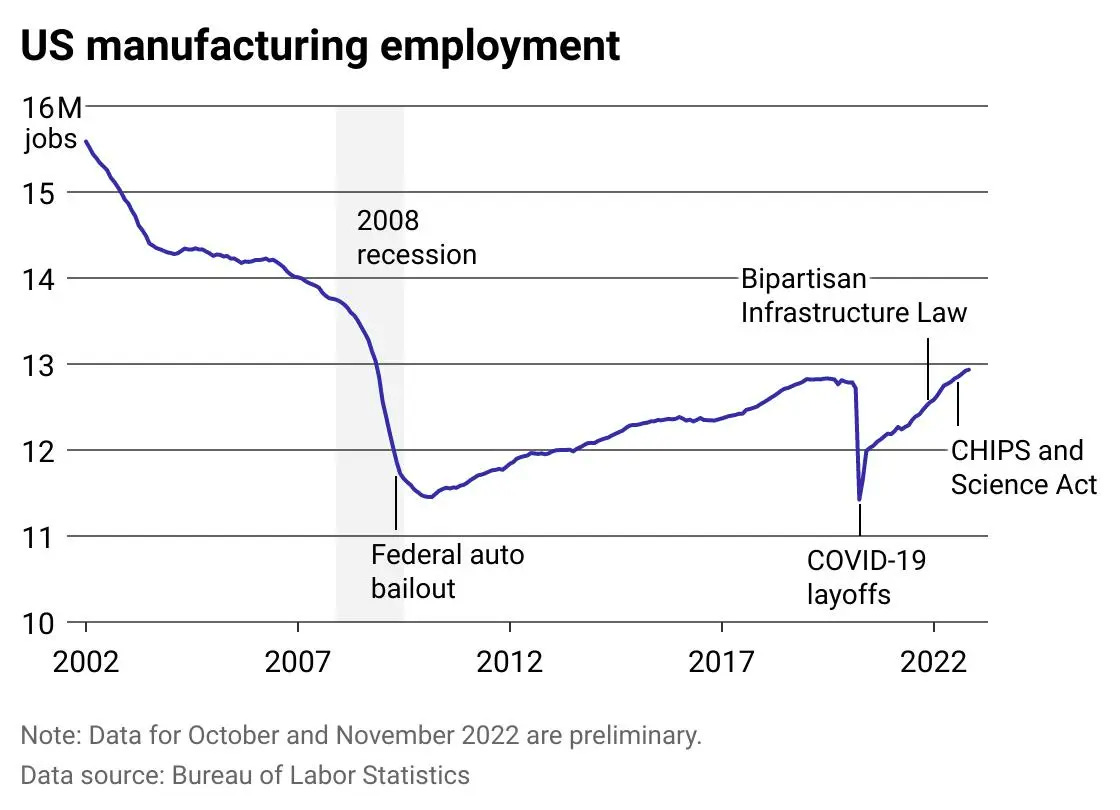

Thus, to boost output, an increase in employment was necessary. Indeed, the manufacturing sector has experienced a notable increase in employment recently, as you can see in the graph below. This increase is due primarily to initiatives aimed at bringing production back domestically and legislative measures such as the Chips Act, which have spurred this upward trend in job creation. While the current state of manufacturing may not mirror the landscape of 2002, this shift could be viewed favorably, given the industry's progression and modernization.

Of course, looking at the number from an overall historical perspective is interesting:

The peak was somewhere in the 1980s. We are not going back there.

Another perspective is the role of manufacturing in the overall economy, measured in terms of manufacturing as a percentage of GDP. It has been steadily declining.

This quick survey is just a background to the fundamental question: Are these new manufacturing jobs “good jobs”? Sure, any job is “good” if chosen freely and helps someone provide for themselves and their family. But let's be honest, some jobs are better than others.

The Current State of Manufacturing Jobs: Wage Fairness Concerns

While there are employment gains in manufacturing, the safety and fairness of these jobs remain uncertain. Manufacturing jobs today are undeniably safer than in the 1970s and fairer than in more distant times. However, when consumers purchase products, they often remain unaware of the conditions under which they were made.

Take, for instance, the garment industry in Los Angeles. Many consumers believe that the "Made in USA" label signifies ethical production standards. The reality, however, is more complex.

The article “Made in America” Never Meant More Ethical” delves deeper into this issue. It tells how workers in the heart of Los Angeles's fashion district work long hours under the piecework payment system, often earning well below the minimum wage. Despite recent legislation like California's Senate Bill 62 aimed at protecting these workers, implementation has been sluggish, leaving many still toiling under exploitative conditions:

“However, more than two years since the bill’s triumphant passage, its implementation has proven feeble. California’s first-ever arrest for wage theft in the garment industry occurred just last month, when Lawrence Lee, a co-owner of a garment manufacturing business, and Soon Ae Park, a garment contractor with a history of stealing wages, were arraigned on felony charges. Their alleged misdeeds included compensating workers with as little as $6 per hour, many earning an average of $350 for a 50-hour workweek. As of the publication of this article, Bilma says she still toils under the piecework system, despite the passage of SB 62.”

Now, this is illegal. But I think it raises a broader question of whether wages in manufacturing are actually “good.” They have increased over time.

However, as you know, we are currently facing a period of inflation. By examining a specific industry, analyzing its real wages, and comparing these to the salaries of management personnel in the same sector, we can observe a stark contrast: Manufacturing jobs are less and less “valuable” in real terms.

When we look across countries, while wages have been increasing in the US, they are not growing as fast as in other countries.

You may ask why.

The explanation is again rooted in the sector's productivity, which has been lagging in improvement compared to other countries:

Why has US manufacturing productivity been lagging?

The decline in productivity is broader than in labor-intensive industries like clothing. The issue is more pronounced in advanced manufacturing sectors. Since 2009, U.S. manufacturing output per hour has grown by a mere 0.2% annually, a rate much lower than the overall economy and manufacturing sectors in Europe and Asia (excluding Japan). Particularly in motor vehicle manufacturing, there has been a staggering 32% drop in productivity since 2012, although some of this could be attributed to pandemic disruptions.

The lack of productivity isn't solely the fault of American workers. Various factors influence it, including management decisions, supply chain efficiency, public infrastructure, and regulatory environments. For instance, U.S. manufacturers utilize fewer robots than their counterparts in Taiwan, South Korea, and China.

Beyond productivity, there are other labor-related issues. The industry faces a skilled worker shortage, and even when skilled workers are hired and trained, retention is low. Many younger workers are not interested in manufacturing jobs (not very surprising given the wages), and absenteeism is a significant issue.

But the outcome is clear: manufacturing jobs are not well-paid and have difficulty remaining competitive over time.

The Current State of Manufacturing Jobs: Safety Concerns

But the issue is not just wages.

A recent article documented the situation at Tesla's Giga Texas factory, where rapid construction and a push for increased production have led to concerning safety issues. Workers face risks from automated machinery, falling objects, and industrial accidents. The injury rate at this facility is notably higher than the median for the automotive manufacturing sector.

As I mentioned above, the situation today is better than it was 50 years ago:

“Worker deaths in America are down—on average, from about 38 worker deaths a day in 1970 to 13 a day in 2020. Worker injuries and illnesses are down—from 10.9 incidents per 100 workers in 1972 to 2.7 per 100 in 2020.”

This data encompasses all industries regulated by OSHA. Therefore, the observed trends may also be attributable to the reduced number of employees working in industries with higher risks of injury. But when comparing across countries, In 2010, the US had 50% more fatalities per 100,000 employees in manufacturing.

But here, one of the issues is that US states are quite different in their fatality rate in manufacturing.

You may ask: What’s the color?

The states are sorted by their manufacturing fatality rates, and the bars are colored differently to indicate whether each state is a right-to-work state. In this visualization, right-to-work states are colored green, while non-right-to-work states are colored blue. “Right-to-work" states in the United States are those where state laws prohibit union security agreements between companies and workers' unions. In these states, employees are not required to join a union or pay union dues as a condition of employment.

I am not making a causal argument here. I don’t. But you are delusional at best if you think these are unrelated. What can be a possible explanation? For example, being appealing to savvy entrepreneurs also means that said entrepreneurs care less about the welfare of their employees. For example, I have already written about Jeff Bezos's approach to human resources, and thus was not very surprised that “Amazon’s worker safety hazards come under fire from regulators and the DOJ.”

While we can quibble about wages, employee safety should be a concern.

The Road Ahead

The resurgence of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. is a complex issue. While there's optimism about job creation, safety and fairness should not be overlooked. Legislation like the Garment Worker Protection Act and the FABRIC Act are steps in the right direction, but effective implementation is crucial for meaningful change.

Furthermore, the role of consumers is increasingly significant. Awareness and advocacy can pressure manufacturers and brands to adopt ethical practices. I have written extensively about our role as consumers regarding product returns. The same is true when it comes to wages and safety. If the product you bought is very cheap, don’t be unrealistic about the practices needed to manufacture it.

As the U.S. seeks to reclaim its position in advanced manufacturing, success depends on factors like management, labor, and cultural aspects of work. Training, culture, and learning-by-doing are essential components that can't be rapidly adopted or transferred. For instance, due to these factors, TSMC's planned fabs in Arizona may face challenges in achieving productivity comparable to their Taiwanese counterparts.

In conclusion, while the demand for higher wages and better working conditions in the U.S. manufacturing sector is understandable, addressing the underlying issues of low productivity, skilled worker shortages, and integrating modern technologies is critical. This involves a collective effort from unions, management, and policymakers to adapt and evolve in a rapidly changing global manufacturing landscape. But to attract more skilled workers, we need the jobs to be safe and competitive. But for that, we need to have significant productivity gains….

In essence, navigating the manufacturing sector's future is a classic chicken-and-egg scenario: enhancing productivity and worker conditions must go hand in hand to ensure sustainable progress.

I think they will come back, especially due to demographic shifts. This video/transcript from Peter Zeihan has some good points about "The Greatest Reindustrialization Process in US History": https://zeihan.com/the-greatest-reindustrialization-process-in-us-history/

Great read! thoughts on recent developments at Figure? https://x.com/figure_robot/status/1743985067989352827?s=46