While most of my articles are written from the comfort of my study, in the small town of Bryn Mawr, once in a while I brave myself and visit the front line of operational challenges ... all for you dear readers. I’ve been on a quest for mustard in France, I’ve stood in line to sample the best falafel in Israel, and this weekend, I am in Utah, skiing and exploring the brewing debate on how to solve the congestion on the road that leads up to the mountain on powder days. The sacrifice is real!

All this brings me to this week’s query: What connects Haifa, Little Cottonwood Canyon, and Medellín?

They’re all either considering or already using gondola systems as a means of transportation. And no, this is not a Valentine's Day edition, so we’ll disregard the fact that the origin is the more romantic, Venetian type.

Below is an image of the new gondola system that just started operating in Haifa:

But what made these Gondolas so popular? Let’s start with Utah.

The Problem

Utah has been observing an increased level of congestion on the road leading to the ski resorts, Alta and Snowbird. According to a recent NPR article, on a busy weekend or after a day of heavy snowfall, it can sometimes take more than three hours to travel the 8-mile road up Little Cottonwood Creek Valley.

What’s causing the issue?

“‘There are just too many people,’ Cardello says. ‘And it’s not [just] here it’s everywhere.’ Many blame discount season passes like the Ikon, which is good at Alta and Snowbird, or the Epic from Vail Resorts, which allow skiers to bounce easily from one resort to the next, and also chase the best snow between states.”

While the number of skiers around the world has not increased, the situation in Utah is different:

“In the last 20 years, the number of skiers visiting Utah resorts has nearly doubled, from 3 million to now close to 6 million, according to Ski Utah, an industry trade group. ‘We have the same infrastructure, the same road that we had 20 years ago,’ says Mike Maughan, general manager of Alta.”

The Solution

The state of Utah has been contemplating multiple options, as outlined in the table below:

A few months ago, the state voted to try and add a gondola system. The Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT) estimates that the solution (referred to as Gondola B) will operate a set of gondolas, each carrying up to 35 people, and departing every 2 minutes, resulting in the transportation of approximately 1,050 people per hour (roughly the same number of commuters who ascend Little Cottonwood in an hour when there is no road congestion).

The estimated cost is $550 million (although it's widely thought that number will increase if construction moves forward).

Before we try to understand the cons and pros in Utah’s case, it’s worth understanding the attractiveness of these systems in general.

Gondolas Around the World

Most of us are familiar with cable cars in two primary settings, ski resorts and, more recently, in certain cities.

Ski resorts have steep slopes and limited options for skiers to reach the top, while demand is usually limited to the ski season, meaning lift tickets are usually expensive. More and more ski resorts are now trying to create demand outside the season, by attracting mountain bikers, for example, to generate additional revenue streams and make better use of their fixed capacity.

Gondolas are also becoming more prominent in cities. Since 2004, Medellín, Colombia, a city known for its violent crime, has invested in connecting neighborhoods (which were previously isolated and therefore low-income) with the rest of the city through its MetroCable system. This investment has been applauded as it reduced the crime rate.

Other cities started following Medellín’s model. Caracas in Venezuela to La Paz, and even New York by transporting people to Roosevelt Island, where Cornell Tech is located.

As with ski resorts, gondolas allow cities to deal with challenging topography, such as steep hills and rivers, but in the urban setting they bring additional benefits: they’re quiet, emit no direct air pollution, and are significantly cheaper to build compared to railways and tunnels:

“A World Bank study of urban cable cars notes that the average journey length for today’s system is 2.7km, with stations every 800 metres or so. They typically reach speeds of between 10-20km/h (6.2 to 12.4mph) and can carry up to 2,000 people per hour in each direction. Depending on the city and the neighbourhoods served, a single cable car line can carry upwards of 20,000 passengers daily. One line in the Bolivian capital La Paz carries up to 65,000 people every 24 hours.”

Back to Utah

But the situation in Utah is different. It’s not a ski resort per-se (the road is already built), and it’s not an urban area with constant traffic.

So why build a gondola system?

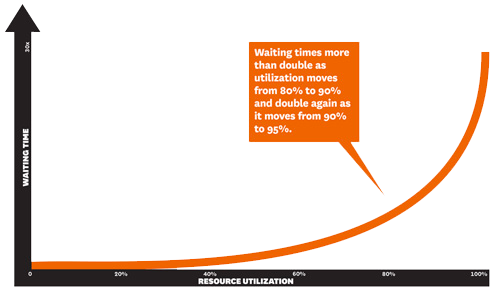

The main issue with the current road is that during peak season, icy conditions and heavy traffic are correlated. So, heavy traffic is making the drive slower (we know that as we get closer to 100% utilization, waiting times become significantly longer):

The situation is exacerbated when people drive slower, or when there’s an accident. These isues don’t just plague cars, but make other means of transportation, such as busses and vans, suffer similarly, unless demand is regulated.

The main advantage of the gondola system is that it maintains its capacity, while its speed can be increased or decreased at the discretion of the operator, regardless of the level of congestion.

The proposed solution aims to keep the road open to public transportation and continue to allow the use of the road for those who prefer to drive their car (with the additional tolls), while redirecting some of the traffic to the gondola system, thus alleviating the overall road load. Using the same graph as above, it’s evident that even a small reduction in the number of cars will reduce travel time significantly.

Another advantage in Utah’s case is that the gondola will have relatively little impact on the landscape or the environment in general (air and noise pollution), when compared to any other suggestion.

The assumption is that private cars will continue to be allowed to use the road. People have been living there for quite some time so it’s not possible to cut them off. You can charge a toll (which could be included in some seasonal passes), but you can’t prevent private cars from using the road. However, this means that any solution that doesn’t involve adding capacity, and just uses the existing infrastructure without altering the road, will be hampered in the on-set.

The Debate

But there are several people against the gondola solution.

The first argument is that the state should try to utilize the existing system and gradually change the economics of the existing resources, primarily around tolls:

“Last Fall, after the state formally announced its preferred alternative, Salt Lake city and county councils of governments both passed resolutions in opposition to a gondola. County councilman Jim Bradley, a longtime environmentalist, is pushing the state to improve its existing bus service with dedicated bus lanes and EV busses. He also supports tolling and tighter traction controls, especially for rental cars which some days account for half of the vehicle load. These are more practical and sustainable, Bradley says, and a gondola in his view would threaten the pristine nature of the canyon.”

As I have previously discussed, there are pros and cons relating to congestion tolls, and given that access in this case is primarily for leisure, it isn’t a bad idea. However, skiing is already an expensive and elitist activity in the US. Do we really want to make it more expensive? In addition, if the toll is not high enough, congestion will largely remain the same. If the toll is too high, it will further increase costs. This weekend, the per-person cost of a ski lift ticket at Snowbird was around $200. So I think it’s safe to assume that an additional toll won’t change things for those who want to use their cars.

When estimating costs:

“‘Our initial studies show that the toll is likely to be in that $25 to $30 range,’ said Josh Van Jura, project manager for UDOT’s Little Cottonwood Canyon Environmental Impact Statement. ‘The gondola fare has to be substantially lower than the toll for roadway users,’ Van Jura said.”

If you’re wondering about the cost per person for the Gondola:

“Heimark assumed during ski season, the gondola would be full, going uphill in the mornings and downhill in the afternoons. “I came up with what I think in [sic] the lowest possible cost of about $90” per rider, Heimark said. But he’s skeptical of UDOT’s construction and operating estimates – which are based on 2020 data – or that the gondola would be full.“ Using those figures, Macfarlane came up with what one could call “the daily cost of using the gondola would be about $17 instead of the $111.”

Then there’s the climate change-related argument:

“‘We don’t know how long this snow is going to be in our Wasatch hills,’ he says. ‘With climate change, which is real, we could have good days and bad, good years and bad years. and we may not need the capacity that they claim a gondola could provide.’– Salt Lake County Councilman Jim Brady.”

But let me add one more argument against the gondola system:

One of the project’s main goals is to “meet peak-hour demand on busy ski days.” How many peak days like that do we have? I would say the week between Christmas and New Year’s, and even if we include every weekend after that for the next three months, that’s a total of about 30 days… and that’s assuming there’s a lot of snow.

And while the main argument for this would be the fact that ski resorts are also built to operate for a limited time of the year, they are stll used for a total of at least 100 days per year (mid-December to mid-March).

One of the main advantages of the gondola solution is that its throughput rate doesn’t depend on demand. But this is also its main disadvantage. It’s not a very scalable solution since it works well during peak time, but it’s not needed during the rest of the year. If demand increases further, I’m not sure I can see a way to increase capacity. Furthermore, the complete infrastructure is needed right from the start, leaving no room for experimenting with gradual solutions.

In addition, the analysis doesn’t seem to account for an important aspect of the service system: the variability of travel time. One advantage of the gondola solution is the fixed travel time, but the reality is that variability is important. For example, when I arrived earlier this week, very late at night, it took my shuttle only a few minutes to drive the 8 miles up, whereas on powder days, it can take 2 hours. But that means that on the days where congestion is low, people on the gondola will wonder why it takes them longer than those driving, and those driving will wonder why they’re paying tolls when there’s no congestion. And if the toll is congestion-based, it will make planning very hard.

Of course, there is the debate about why the state should fund something only a small part of the population enjoys, but here I tend to agree with Alta’s CEO:

“‘It’s like any other public works throughout the nation, whether it’s a bike trail in some rural community or a tunnel somewhere,’ Maughan says. ‘Only certain people use those public improvements but they’re paid for by everybody.’”

The final decision on the gondola in Utah is still pending, and one has to applaud the state for its willingness to be bold and invest in infrastructure, when the tendency is to be frugal. As someone who visits Utah for a conference that happens to take place at a ski resort, I like the fact that it’s not that easy to get in and out. It makes the conference better since all participants stay close, making the evening and slope-side discussions much deeper. This, of course, isn’t an argumen for the state of Utah, but it definitely made Snowbird and Alta more appealing to us. Sometimes congestion is a good self-regulator.

"This weekend, the per-person cost of a ski lift ticket at Snowbird was around $200. So I think it’s safe to assume that an additional toll won’t change things for those who want to use their cars."

Isn't the relevant behavioral change not about Ski vs. Not Ski, but instead Drive Alone vs. Carpool or Bus or Other? On a big snow day, $200 is worth it. $250 is still worth it. If you told me it was $250 if I drove myself (and sat in traffic for 3 hours) and $225 if I rode a clean, comfortable, wifi-enabled bus where I could read a book and relax with my friends - I'd economize! Getting behavioral change at the margin like this could reduce travel times for the majority in a big way.

"...In this case we’re really tolling to help reduce congestion and then raise the revenue for transit, which further reduces congestion."

This is your quote from the MTA approach to congestion pricing in NYC and I think it applies!

But this didn't make sense to me:

"...the analysis doesn’t seem to account for an important aspect of the service system: the variability of travel time...and if the toll is congestion-based, it will make planning very hard."

Isn't travel time variability pretty easy to understand, though? Google Maps and common sense (time of day, snow forecast, etc.) can let me benchmark the cost of paying a toll, and certainly the Utah tolling authority could publish rates and historical data.

This reminds me a bit of street parking in NYC. We give away the most valuable urban land in the world, for free, for private vehicle storage. And then folks complain about the shortage of free street parking!

I really believe in the Coase theorem. If the system is clearly defined with no gimmicks, the people who consume scarce and expensive infrastructure (and inflict significant externalities on their neighbors) can and will pay accordingly, and our infrastructure will be much more productive and financially solvent.

I'm not going to lie, when I first read the title, I couldn't help but scoff. Surely Gondolas are gimmicks and only useful for uneven and elevated terrain. However, once I started reading and thinking, I really do believe in its viability, especially when addressing the problem of road congestion. As you mentioned above, whereas roads get more inefficient as conditions deteriorate and the number of people increases, Gondolas could maintain their throughput.

I feel that I, and many others in the US, have an auto-focused mentality, hence my original reaction. It is interesting to see how alternate forms of transportation have been implemented successfully around the world and how we may eventually apply those lessons to our cities here.