On the P-Value of Scaling: Growth vs. Operational Excellence

Earlier this week, Insider published an interesting article on the new initiatives at GoPuff.

“Last year, the rapid-delivery company Gopuff started adopting the Amazon playbook for running warehouses — and that included grilling managers over why workers were taking bathroom breaks.”

The order of the day at GoPuff is hitting metrics — almost at all costs. Former Gopuff managers said the pressure to make sure the company was hitting its benchmarks of delivery times and pack times was so intense that their bosses often called out employees who took bathroom breaks.”

While the bathroom breaks are the lightning rod of this article, they only scratch the surface:

“For instance, last year when Gopuff instituted companywide metrics for the maximum time workers should take to pack a bag, managers had to redirect employees who were receiving shipments and put them on packing duty. That contributed to a problem of deliveries piling up outside warehouses and going to waste, according to three former Gopuff employees.”

The article is quick to blame these new approaches (including restroom breaks and attention to metrics) on GoPuff’s extensive hiring from Amazon, which is known for its brutal attitude toward employees (something we documented before), and operational excellence.

But as usual, things run deeper. To some extent, this article highlights the two approaches within the startup world: the Uber way vs. the Amazon way.

The Uber way: grow at all costs, and optimize later (maybe never), once you achieve massive scale.

The Amazon way: always keep the notion of cost and frugality as an essential part of every initiative. Grow, but make sure to optimize for efficiency.

I won’t argue whether one is better than the other. In fact, a firm probably needs a bit of both companies’ DNA to ensure success, but in this post, I want to highlight the difficulty of switching between these two mindsets “midstream” (sorry, I had to).

We’ve already discussed premature scaling (and specifically within the context of GoPuff), and in that discussion, we described the six stages of a startup: Discovery, Validation, Efficiency, and Scale, followed by Sustainment and Conservation. The main idea is that firms should not scale aggressively until they have product market fit (Validation), and have found a way to build a repeatable and predictable path to profitability (Efficiency).

But founders and operators usually ask me:

Why do I need to become efficient?

What does efficiency really mean?

So rather than talking about stages, let’s talk about activities. Startups need to engage in two activities: growing and improving economics (either at unit or customer level).

We can all agree that the hardest thing for a firm to do, is to grow; to find a market big enough for customers whose willingness to pay for the product (or service) far exceeds the cost of production, and whose lifetime value far exceeds the cost of acquisition. But growth is crucial. Paul Graham defines a startup as a “company designed to grow fast.” Let’s read that again: designed to grow fast.

So you can just say, let’s try to grow as fast as possible, and once we achieve a massive market share, we can start working on the unit economics (i.e., the Uber way). But this is exactly what premature scaling is: burning through lots of cash without the promise of ever becoming profitable.

So if growth for the sake of growth is wrong, and there’s no time to stop and wait for Efficiency, why not do both?

Why not Both?

Because it’s extremely difficult.

The first and maybe more obvious reason, is limited managerial attention and time. Management only has so many hours in a day. If those hours are spent on meetings about how to improve margins, they’ll improve margins. Similarly, if all hours are spent focusing on growth, they’ll grow. It might be time-consuming and expensive, but they will eventually grow almost as fast as they want (at least their revenues). Achieving both is difficult since spreading attention across multiple activities usually results in subpar outcomes.

The second reason is that if you try to grow while also trying to improve margins, you will realize that the two are actually in conflict with each other, at least in the short term.

Why?

Growing usually means adding more products (or services). If you’re adding more products, it’s very hard to improve your demand forecasting methods for them. Forecasting demand is hard as it is. Forecasting for new products is even harder. Forecasting demand for existing products while adding new “competing” products (and reducing the number of data points you have on each product) is a real head-scratcher. So if your forecasting is bad, you’ll have to carry a lot of inventory (which is costly) but also wasteful. Just like GoPuff.

The same goes for pick-and-pack times; a major factor in unit economics. As you grow and add more products, warehouse workers will be required to pick baskets of products that are farther apart from each other. When you grow slowly, you can optimize your warehouse layout, routes, and technology to pick and pack. But if you add products too fast, optimization is futile. What’s the point of optimizing your warehouse if there’s a different set of products the following week? So picking and packing times are going to suffer as the firm grows, and with them, the “cost to serve.”

When there’s pressure to grow, you’ll add customers without considering their location, which will hurt your drops-per-hour metric (or any other metric you use to optimize delivery performance), impacting your unit economics negatively. Once again, it’s hard to optimize routes, or even build a strategy around them, when your main focus is to add customers at an insane speed.

And this also applies to customer economics. When you’re trying to grow, you have to use whatever channel is available to you, so you can’t improve your customer economics (the CAC to LTV or payback period).

I hope these examples illustrate why it’s hard to do both at the same time.

But let’s go back to the two activities: growth and improving margins. Which one should we prioritize at any point in time? I argue that both are important and both never go away. They are two activities you need to weave together and learn to constantly switch between. But it’s important to learn how to improve margins relatively early in the life of a startup. Especially for a heavy operational startup.

Why Learn to Become Efficient?

The main reasons to “learn” how to solve the contribution margin issue early is:

to become more attractive to customers,

to show that there is a path to profitability, and

because it’s easier to develop discipline and margin improvement capabilities early in the life of a firm.

Why is it easier to develop such a capability when you are small? To improve your contribution margin, you need to find a way to cut costs. Cutting costs is easier to do with 10 products rather than 10,000. It’s easier to build suitable forecasting methods, and then scale them, rather than start to develop them when you are adding thousands of products per week. The same is true for routing and logistics.

So by developing this “muscle” and laying the foundation for operational excellence with fewer products, you can build on it later when everything becomes more complex. So in the future, when you start adding products (or locations), and you see a deterioration of your economics, you can let things worsen a bit since you know that once you focus again, they will improve. You treat it more like a local tradeoff that you’re making at this point in time rather than a stage.

Ultimately, what you’re doing is building capability for both the short and long term. Short term: actually cutting costs. Long-term: knowing that you can be tolerant, as the priority is to step on the gas pedal and grow, while knowing that you can cut costs again in the future, when needed.

But just like all things, there is always risk.

If you become a little too “addicted” to cost reduction, you may become too conservative in how you grow, since any new growth will challenge your cost metrics.

Similarly, if you focus on retention, to improve your CAC to LTV for example, you will only acquire customers that are likely to stay with you, becoming potentially too conservative with new customers at a time when you shouldn’t. Of course, no one wants to have a leaky bucket, so as usual, there is no simple solution.

So this is exactly where “developing the muscle” or the capability is essential. The ability to drive costs down while accelerating growth is not trivial and thus should be part of the arsenal of the firm as it grows. And this is especially crucial for operationally intensive business models. You need to find a way to grow, but you need to develop operational capabilities as you grow.

Mini Case: Meal Kits

The meal kit industry provides a good reminder for this.

Blue Apron defined this industry and indeed grew faster than anyone else:

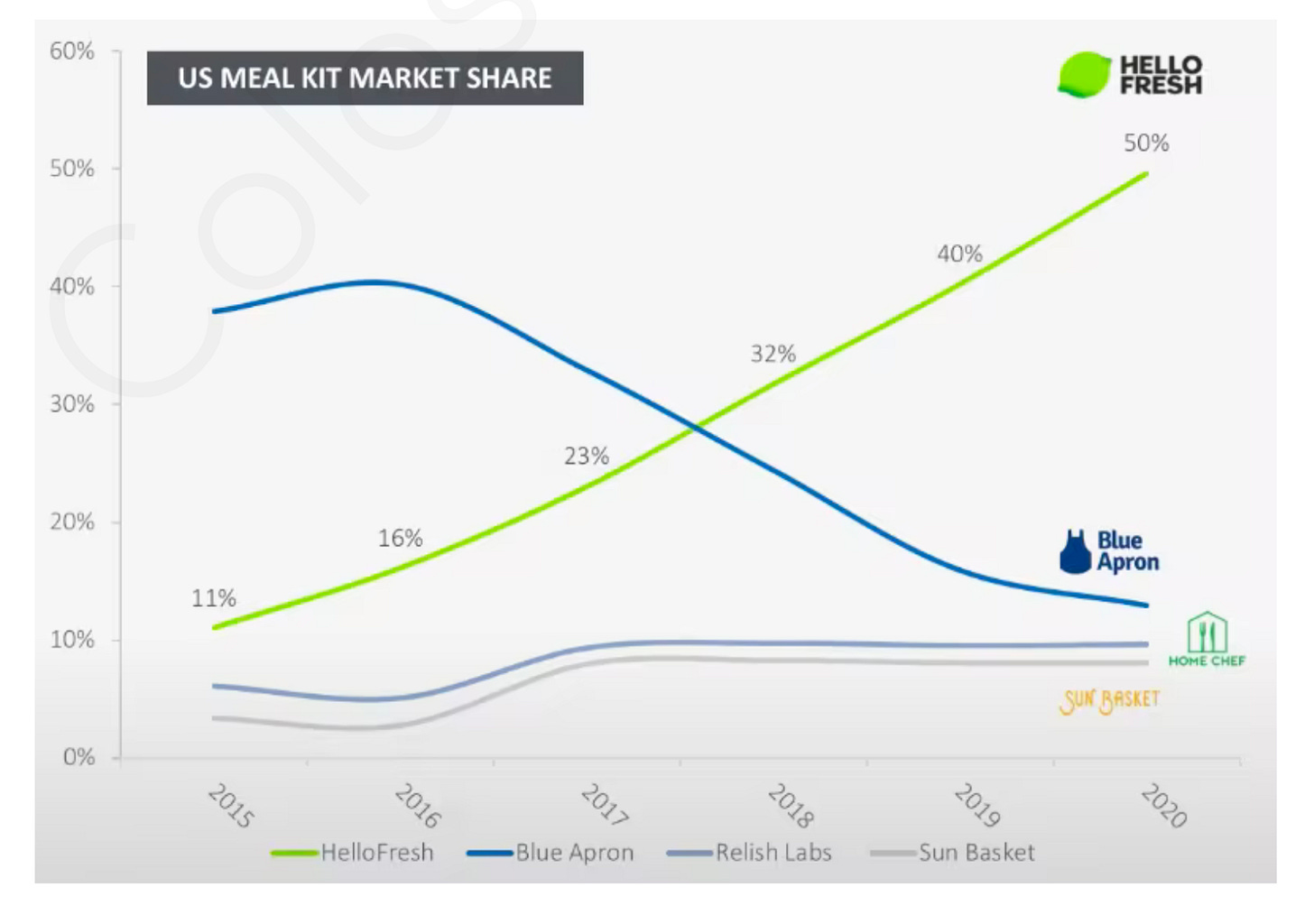

HelloFresh started much later (and slower), but at that point, the news of Blue Apron’s very inefficient operational system, and loss of customers due to many mistakes, had already come out.

Now, it’s not that HelloFresh didn’t have retention issues, but it was much better at delivering profitability, and soon, it started taking the majority of the US market share…

…and ultimately took over Blue Apron. HelloFresh definitely invested in growth, but it has also built impressive operations:

“HelloFresh has prioritized and made significant investments into a fully vertically integrated supply chain. Its facility network, built over 6 years now operates on a large scale, with a network of 1,500 suppliers. HFG has invested over EUR500M in its state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities and automation technology till date…It has a 4 year head start on Supply Chain Automation Technology explicitly designed for the meal kit business and its intricacies. These compounding advantages will not be easy to overcome for a potential new entrant, particularly, because of how hard it is to develop such networks in the physical world.”

While neither of these firms is doing great these days, in terms of stock price, HelloFresh is doing ok while still being profitable, something that can’t be said about Blue Apron.

Their market caps illustrate this point, with HelloFresh at EUR 3.94B and Blue Apron at $154.49M.

I’m sure you can find a counter-example, but the orthodoxy among many VC’s still is that you should grow at (almost) all costs.

In the same way that knowing how to grow is a capability, Operations is a capability too. You may need to know when to use it and when to relax a bit (so you can use it again). But it is a capability.

And if you don’t use it early, you may need to develop it when things are a bit too complex. And then the tendency is to nit-pick at the wrong things. The visible things … like restroom breaks.

Thank you for another informative blog. I am curious for opinion on example like Snowflake? Does it qualify to have developed the muscles of both growth (undisputed) but also sign of efficiency? (from its young life as a public company in the past 2 years post-IPO).

Professor, what a great article and resume for those who work at startups companies. A daily challenge we leave and constant trade off we have to take to shift the strategy while growing. I say is like try to change the tires of an airplane while taking off.