Pool is Back

A couple of weeks ago, Uber announced that they are bringing back UberPool. It won't be called UberPool anymore, and the new service, UberX Share, will have a few differences with its predecessor.

The service is currently only available in a limited number of cities, such as NYC, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, and Pittsburgh…but not Philadelphia.

The key differences, compared to the original UberPool, are that in the original service, the price was guaranteed (and significantly lower than UberX; we will get to that soon), and it was possible to book more than one seat.

In the new UberX Share, riders will be matched with another (co-)rider who is headed in the same direction, and it’s guaranteed that no more than one additional person will be allowed to share the ride at any point in time. The service is not as cheap as the original UberPool, but Uber plans to offer up to 20% off on the total fare if a customer is matched with a co-rider, and if there’s no match, Uber will offer an upfront discount, the amount of which will vary (reports on this are not yet precise). All we know is that fares for an UberX Share will always be lower than an equivalent UberX, but not much lower.

Before we try to understand the new service, let’s first take a look at the original idea.

Why did Uber Launch UberPool?

Uber has generally had a hard time making money. The unit economics shown below are taken from a Tweet that analyzed the numbers across all ride services globally, based on its S-1:

So on average, Uber loses money on every single ride.

When UberPool was introduced, customers paid a much lower price, but in return, they had to most likely share the ride with other people, and endure a longer trip (since picking up and dropping off other passengers would add to the original travel time).

For Uber, this seemed appealing since they believed that these pooled rides would increase their revenues. Theoretically, a single driver would receive the same payment amount based on distance, trip length, and time of day (regardless of the number of passengers), and at the same time, multiple passengers would be paying separate fares for their ride (regardless if it was for the same trip). This should have allowed Uber to do two things at the same time: lower ride prices, and make money. In fact, one can see how this could have been a great flywheel: the more passengers you have on a route, the lower the price. The lower the price, the more people you attract, which then allows you to lower the price even further.

But there was also one more aspect: Uber has been widely criticized for increasing congestion and pollution in the cities in which it operates. UberPool was a way to show that the firm was trying to address that.

So three goals in one new service: growth (attracting price-sensitive passengers), financial viability (start making money), and sustainability (operating closer to public transportation).

The Problem

Only the first of these goals actually worked.

The price was indeed significantly lower, usually half the price of an UberX on a similar route, but at that price, it was almost necessary to have at least two passengers to make the trip economically viable. The problem was that most UberPool rides continued to have only one passenger.

Based on a somewhat limited, but probably quite representing study done by the RideShareGuy and summarized here, most rides had only one passenger, and in fact, Uber lost money on 80% of its UberPool rides:

At the time, Uber announced that, globally, 20% of the rides were pooled, so do the math. It is said that in SF only, Uber lost $1M a week on UberPool rides. According to some estimates, Uber rides were on the order of 1M trips per week before COVID, and if 20% of them were UberPool, that means the firm lost around $5 per UberPool ride. And this for a small city with clear pick-up and drop-off locations.

If you are wondering why it was so cheap, yet so economically disastrous, we need to look at the numbers and economics in combination with consumer behavior.

Several years ago, Uber published a study on the sensitivity of customers regarding different features of UberPool.

This study contains several interesting but counterintuitive behaviors. For example, customers are not that sensitive to the variance of time (the blue line). I find this somewhat surprising since we know from service operations that people hate to wait, but they hate uncertain waits even more.

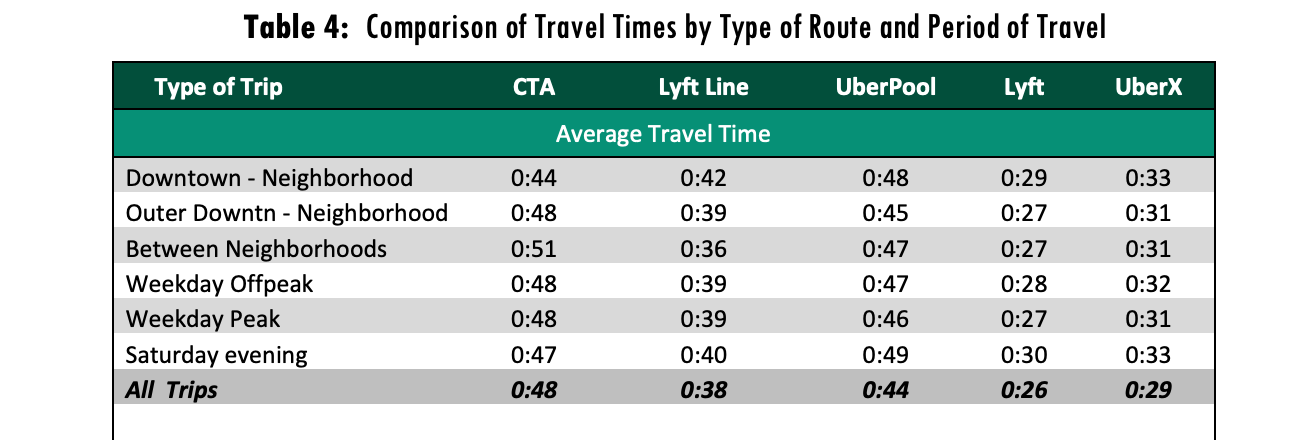

According to some studies conducted in Chicago, the deviation of UberPool, both in terms of price, but more so in terms of time, was very high:

So apparently, this isn’t something people care about.

But let’s continue. One explanation as to why most of these Pool rides are solo rides, is that they are lacking the necessary density from origin to destination. For example, I’m quite sure there are multiple people who want to get from Huntsman Hall (Wharton’s home) to PHL (Philly’s airport) for their scheduled weekend getaways on a Thursday afternoon (who am I kidding, it’s most likely on a Wednesday afternoon, but not before my class. Serious students don’t leave before my class). I’m also sure there are many people who leave Wall Street every weeknight around midnight, heading to the Upper East Side, but they’re probably not UberPool riders. So it’s hard to find routes with consistent demand and supply that also have the right price sensitivity and the right target group on a regular basis.

What makes things worse is that (as you can see in the olive-green line in the previous graph above) customers are unwilling to walk a few blocks for pick-up or drop-off in order to generate slightly more density (however small). I find that somewhat surprising too, since only a few blocks may make a big difference in the price. Density is absolutely essential to make these trips more efficient.

But it’s clear that there are a few things customers are more sensitive to.

And those would be the length of a trip, and the price of a trip.

Regarding the length, it is interesting on multiple fronts. First because UberPool trips are significantly longer, and second, because they will potentially become even longer with UberX Share (since you can only book one additional seat).

Regarding the price of a trip: These are the prices in Chicago taken from the first service, UberPool.

To convince 20% of people to use UberPool, Uber had to offer a very cheap service. Some of these customers Uber “stole” from competing services (such as Lyft or public transportation), and some were cannibalized from UberX.

But if you try to understand why the UberPool system achieved only one of its goals, customers did play a big part in it since they are very price-sensitive and somewhat unwilling to tolerate too much inconvenience.

Uber lost a lot of money on these rides, and drivers hated them since they got paid the same amount, and customers tended to leave worse reviews (even if it usually wasn’t the driver's fault for having a very meandering route).

So even towards its IPO, Uber increased the price of UberPool to make it slightly more viable.

Then, COVID struck, and Uber realized that given how hard it is to convince customers to take Uber (considering the health risks), and how hard it is to convince drivers to get back on the road, they ditched the pool service completely.

But Sharing is Caring, so it’s Back

Different name, slightly different terms.

The reason for the different terms is clear: Uber’s CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, has already said that given the economic situation, additional focus is going to be put on unit economics.

So let’s see.

Uber’s customers are still price sensitive. In fact, with the increase in gas prices, and the continuing shortage of drivers the past few months, Uber’s prices are quite elevated. Given these high prices, which are coupled with limited discounts, I expect only very few people to try the new UberX Share.

And indeed it seems that people are not really using it. If it’s not being used, density will be low, which means prices will remain high. As prices remain high (and the uncertainty of whether you will get paired or not remains high too), fewer people will use it…and so forth.

It’s like a flywheel, but in reverse. It starts slow and becomes slower, and slower, until it stops.

So why try?

In my opinion:

Some of it lies in desperation: Uber needs to find a way to make money, and it just doesn’t have that many options in such a competitive market. Competing on customers and on drivers makes it hard to make money on a consistent basis.

Some of it lies in an effort to see if consumer behavior changed: Maybe customers changed with COVID and people are not as price-sensitive as before. Maybe the remote work era changed transportation patterns.

And some of it probably lies in Uber’s internal political pressure: Before COVID, the UberPool people had 20% of the rides. And for the last few years, nothing. I am sure there is pressure within the firm to resurrect it.

But this brings me to another point. Over the last few years (even before COVID) we saw very little innovation on Uber’s ridesharing aspect (unlike UberEats and grocery delivery). Same products, worse interface, higher prices (for which Uber is not always exclusively to blame), but nothing beyond that.

Is everyone just waiting for self-driving cars? Is nothing going to happen between now and then?

One thing I liked about Uber was its global aspect. I can open the app anywhere and quickly find a ride. However, I am currently on a global trip between Munich, Tel Aviv, and Mumbai, and my experience so far has not been what I was expecting. In Munich it was ok (meaning, similar to what I’m used to in the US): long wait times and expensive rides. In Tel Aviv it was non-existent (it’s called UberTaxi, which is short for “the worst of both worlds”). In Mumbai, I was quoted 22 minutes for a ride this morning and then had several drivers cancel the trip altogether.

Were we all spoiled in the days of cheap, fast, global transportation? And are these days long gone? Or are we still in the COVID-19 after-shock and can expect better days ahead?

Mobility is such an important part of our lives, that I’m hoping for the latter. But for that, we need the operating firms to wake up and start innovating again.