Rethinking Airplane Boarding: Balancing Efficiency, Preferences, and Real-World Complexities

I’m quite sure I’m “preaching to the choir” here when I express how crucial air travel efficiency is both in the grand scheme of modern transportation and for our mental health while traveling, but it’s a topic that needs to be addressed all the same.

In this bustling world of air travel, airlines are constantly trying to enhance passenger experience while streamlining their processes. United Airlines, for example, recently rolled out a new boarding procedure named ‘WILMA’ (window, middle, aisle), the implementation of which primarily affects economy class passengers —boarding for premium cabin passengers and frequent flyers with elite status remains unchanged through Group 2. The new strategy further divides Groups 3 to 5 to board in order, starting with those seated by the windows, followed by passengers in the middle, and finally, those in aisle seats.

The policy doesn’t affect me yet —it only starts at group 3; at this point, I usually pre-board— but if I should lose this dubious status, I’ll have to balance my love for aisle seats (I enjoy freedom) and my love for boarding early (I need space for my carry-on and I like to board and get settled quickly so I can either immerse myself in a book or drift off to sleep, all while relishing the thought of an on-time departure).

WILMA clearly seems like an improvement, but in early experiments, United claimed that the total boarding time only improved by 2 minutes, which doesn’t sound like much.

In today’s analysis, I delve into the effectiveness of United’s WILMA method compared to other commonly used boarding strategies and show that while the policy should be an improvement, in reality, it’s less appealing.

The Challenges

Despite the potential time-saving benefits of United Airlines’ new WILMA boarding process, several passengers have expressed concerns and grievances regarding its practicality and fairness.

Passenger Inconveniences and Preferences

Some passengers perceive the WILMA process as inconvenient, especially those paying higher fares but still waiting longer to board. This sentiment is particularly strong among passengers who prioritize boarding early to secure overhead bin space for their carry-ons —a benefit traditionally associated with higher-priced tickets— but also prefer aisle seats.

A critical factor in the boarding process is the availability of overhead bin space. United has recognized this and is in the process of retrofitting its aircraft with larger bins; expected to be completed by 2026. Until then, passengers in later boarding groups might face challenges in finding space for their carry-ons, potentially negating the time-saving aspect of WILMA.

Passenger Behavior and Efficiency

The efficiency of any boarding process heavily depends on passenger behavior. For example, as a frequent traveler, I’m always frustrated with passengers who take their time to fold their coats, place them above their luggage, and arrange other personal items before sitting down. That additional time can significantly impact the overall boarding speed, so even with a structured process like WILMA, delays can occur when passengers take excessive time to settle into their seats.

Continued Priority Boarding

Despite the changes, United will maintain priority boarding for passengers with disabilities, unaccompanied minors, active military members, and those with first or business-class seats, as well as status flyers or those with certain credit card benefits. This approach ensures that passengers with specific needs or privileges continue to receive the advantages they are accustomed to.

In fact, United’s experimentation with WILMA is not new. Following the introduction of its Basic Economy ticket, the airline tested the method in 2017 at five airports. So why didn’t they stick with it? It is also noteworthy that other airlines have also trialed similar systems but often reverted to traditional priority boarding for premium passengers.

So in summary, while the WILMA boarding process aims to enhance efficiency, its effectiveness and acceptance largely depend on passenger behavior, seat preferences, and the particularities of overhead bin space. The varied opinions among passengers and the ongoing adjustments to aircraft infrastructure illustrate the challenges airlines face in optimizing the boarding experience.

The Analysis: Simulating Different Boarding Strategies

But as usual, we’re not ones to be satisfied with mere qualitative discussions, so toward this end, I conducted simulations to compare various airplane boarding methods, including United’s new WILMA process. My goal was to understand how different boarding strategies impact the total boarding time, taking into account factors such as aisle blockage and passenger preferences. So, for those interested enough to delve deeper…:

Simulation Steps and Assumptions

Passenger behavior: I created a passenger model considering individual walking speeds, time taken to stow luggage, and seat shuffling. These factors were modeled based on somewhat realistic assumptions, such as a Gaussian distribution for walking speeds with a mean of 1 and a standard deviation of 0.2.

Boarding Methods: I simulated several boarding methods, including back-to-front, window-middle-aisle (WMA from now on), and a realistic WMA (the first third prefer aisle seats in the front rows; and the rest are random). The idea of modeling a “realistic WMA” was to address the fact that United, like most airlines, already has certain priorities they must honor, such as frequent flyers, business class passengers, etc.

Aisle Blockage and Sequential Movement: My simulations also accounted for aisle blockage when passengers stow luggage or shuffle into seats, delaying subsequent passengers. This was meant to capture a realistic and common bottleneck in boarding.

Running Multiple Simulations: Each boarding method was simulated 100 times to account for variability and to obtain a distribution of boarding times.

Results

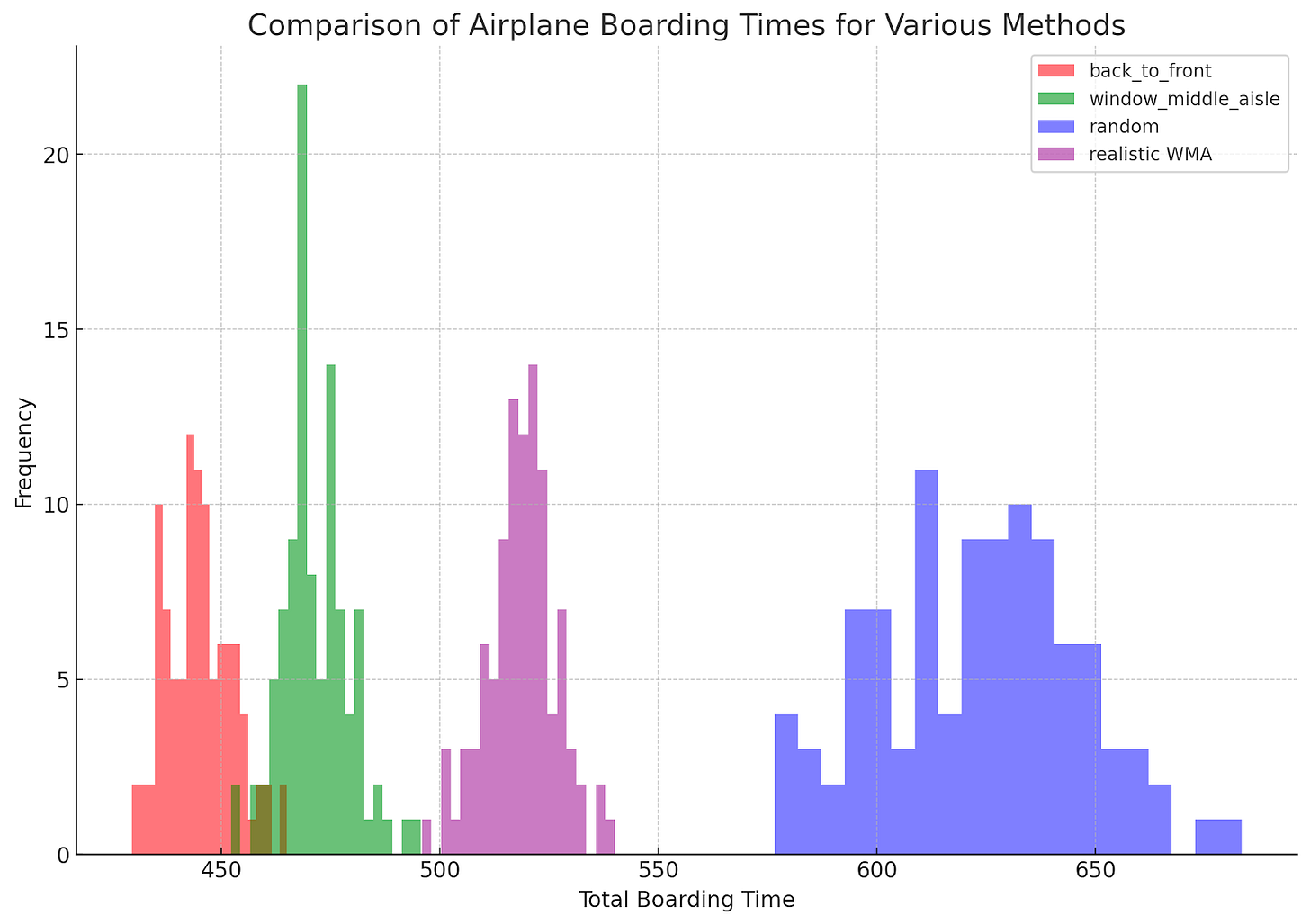

The following figure shows the boarding time distribution for each method. As is evident, Back to Front outperforms the rest, followed by WMA (whether realistic or not), and lastly by the random system, which is pretty much what is done today.

As you can see, while the ranking is clear, the simulations suggest that no single method consistently outperforms the others in all scenarios. So each boarding method’s efficiency depends on various factors, including aircraft layout, passenger behavior, and luggage handling, which may add variability to the method.

The simulation also suggests that WMA’s performance isn’t as good as it seems. Once you impose realistic constraints on it, the improvement is not as high as expected. It is still better than random boarding but significantly worse than the optimized WMA.

Finally, it is important to note that all other methods not only are better than random boarding, but also have significantly less variability. In general, the variability of the boarding process is as much of an issue as the mean. Admittedly, the turnaround time between flights is limited, so there is not a lot of freedom to start boarding early, but making it more predictable reduces the need to pad the time between flights.

A More Nuanced Problem

Nevertheless, the quest for an optimal airplane boarding strategy is more intricate than it appears, as the study Is Back-to-Front Airplane Boarding Optimal? reveals. The paper challenges traditional approaches to boarding and highlights the complexity inherent in achieving boarding efficiency.

Challenging the Focus on Reducing Interference

The prevailing belief in the airline industry has been that minimizing passenger interference leads to faster boarding times. However, the study presents several key findings that challenge this assumption.

Interference and Boarding Time: Contrary to conventional wisdom, the study finds that more interference doesn’t necessarily result in longer boarding times. In reality, they may increase individual boarding times without significantly impacting the total boarding time.

Individual vs. Total Boarding Time: A significant takeaway from the research is the distinction between individual and total boarding times. The study reveals that strategies which effectively reduce individual boarding times don’t necessarily mean a corresponding reduction in the total boarding time.

This is an interesting observation and basically means that ultimately, everyone has to board. Improving the waiting time for some may mean deteriorating the boarding time for others. It’s like a queueing system, where you can serve people First In First Out, or Last In First Out. Both result in the same average waiting time, but in each one, different people may have vastly different experiences.

I know, airlines are slightly different, but if, like me, you believe that aisle blockages are an issue since they slow everybody down, even though the question seems to be mostly empirical, the point is still valid and interesting.

Reevaluating Seat Assignment and Boarding Strategy

I think the most important idea in the paper is that it emphasizes the importance of considering both seat assignment and boarding strategy in tandem. The research approaches the boarding process as a joint optimization problem, asserting that both seat assignments and boarding strategies need to be optimized together. This approach acknowledges the significant impact that seat assignments can have on the effectiveness of a boarding strategy.

And this is exactly what we observe with the “realistic WMA.” Seat assignments matter a lot when considering the boarding speed. The paper posits that strategic seat assignments can potentially reduce the total boarding time, especially when paired with a compatible boarding strategy.

The findings suggest that airlines might need to rethink their standard boarding practices and discover more efficient ways to board passengers. My thought would be to also combine this with better luggage handling. Airlines could offer passengers a way to secure space for their luggage (the same way they secure their seats), or find faster ways for passengers to collect their checked luggage upon arrival. However, the fact that we’re tying all three issues (seats, luggage, and boarding priority) together, might not end well.

Nevertheless, the research shows, as expected, that the back-to-front boarding strategy can be optimal, depending on seat assignment. The paper also delves into the worst-case scenarios for the back-to-front strategy, analyzing its performance with the worst seat assignments and comparing it to optimal boarding strategies, as I suggested above.

In summary, the nuances and complexities highlighted above underscore the need for a more holistic and integrated approach to airplane boarding strategies. Understanding and addressing these complexities could be key to unlocking more efficient, passenger-friendly boarding processes. But the issue is that airlines tend to think too incrementally. I’m a fan of continuous improvement, but sometimes, you must rethink the problem. This is one such case.

So, as we toggle between aisle preferences and early boarding perks, the quest for the ideal boarding strategy continues — much like finding the elusive perfect seat on a plane, which, let’s face it, is probably located next to an empty one.

Always enjoy reading your articles, Prof! Unfortunately this sounds like another excuse for airlines to charge us more money:

"My thought would be to also combine this with better luggage handling. Airlines could offer passengers a way to secure space for their luggage (the same way they secure their seats), or find faster ways for passengers to collect their checked luggage upon arrival."

As a frequent traveler for business, one thing I noticed causing time to board planes is that certain people struggle to lift suitcases or other things above their heads and into the bins. Certain people with weak hands and arms (sometimes women, kids or elders) struggle with lifting bags above their heads and onto the bin. I typically help people when I notice their struggles, but not everyone helps. In my opinion, this another cause for delays.