Over the past few weeks, there’s been considerable discussion regarding Walmart’s investment in expanding its number of stores. This topic is particularly interesting when considering the current state of retail vacancies. Unlike office spaces, retail vacancies are exceptionally low, indicating a robust demand for physical retail locations.

It’s also interesting that despite the significant changes the internet brought to shopping habits, online purchases still account for only about 16% of total retail sales, which highlights the ongoing importance of physical stores in the retail landscape. As the graph below shows, the growth of the e-commerce market share has plateaued:

These observations raise an important question: Was the “retail apocalypse” ever genuinely accurate? This term, often thought to have originated during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, describes a scenario where physical retail was presumed to be decimated due to various challenges. However, the current trend of thriving physical retail spaces and growing consumer interest in in-store shopping prompts a reevaluation of this idea.

The Origin of Retail Apocalypse

The term, which predates the COVID-19 pandemic, originated with the rise of Amazon and online commerce. This period saw significant disruptions in the retail sector, further emphasized by stores of well-known brands such as Toys R Us, Borders, and various electronics retailers, declaring bankruptcy and closing. This was mainly in response to the competitive advantages of online retailers, including Amazon, who promised consumers a wider variety of products and lower prices. The underlying message was clear: online shopping was the superior option for those seeking anything, especially at a lower cost.

One way to reveal the significant disadvantages of brick-and-mortar stores is to examine the type of products they can carry. Marshall Fisher and his co-authors present an interesting graph with critical insight for physical retail to succeed: to be viable in a brick-and-mortar store, products must either be fast-moving items or have high margins.

According to their analysis, most other products are better suited for online sales. And this was indeed the main way that online retailers made inroads into their competitors (a.k.a traditional retail stores). They offered unlimited variety (“The Everything Store”) at low cost by shipping from centralized warehouses located in cheaper locations.

This perspective has led to a significant shift in the retail landscape, with most firms initiating or expanding their online presence (or going bankrupt).

Omnichannel to the Rescue

Over time, however, it became evident that focusing exclusively on online retail may not always be the best strategy. This realization prompted retailers to consider a more balanced approach (combining online and physical sales channels), hence the emergence of omnichannel retail —a strategy which recognizes that physical stores can still play a vital role by offering specific functions. These include allowing customers to assess the fit and feel of products firsthand (crucial for certain purchases) and contributing to brand awareness (an essential factor despite the associated costs). The omnichannel approach addresses the challenge of scaling online customer acquisition, where attracting customers individually becomes increasingly difficult over time.

For example, regions experiencing growth in physical retail infrastructure also show an uptick in online shopping activity. A recent ICSC report titled “The Halo Effect III: Where the Halo Shines,” examined 69 retailers from 2019 to 2022 and revealed the following: Opening a new store can significantly boost a brand’s e-commerce business, with a 6.9% increase in online sales within the trade area during the following 13 weeks. For emerging retailers, the increase is even more pronounced at 13.9%. Physical presence resulted in a 37% rise in overall web traffic, and while the numbers were not favorable for cosmetic brands (4.6% decrease), department stores and apparel retailers saw an increase in online spending of 50.6% and 11.6% respectively. The study found that post-opening, the average online basket size grows from $94 to $104 for established retailers, and from $111 to $120 for emerging brands. Conversely, closing a store has a detrimental effect, shrinking online sales by 11.5% across all retailers, with home stores, department stores, and apparel chains experiencing significant drops in online and total spending.

This trend suggests that, at least in certain contexts, physical and online retail can complement each other. However, it’s important to consider these findings with caution. The increased online activity in areas with more retail development could also be attributed to higher consumer awareness, greater disposable income, or overall increased economic activity rather than a direct causality between retail expansion and online shopping growth.

The Drivers of Omnichannel Retail

One possible trigger for what the ICSC report finds can be demonstrated through a study authored by my colleague Santiago Gallino and former colleague Toni Moreno, “Integration of Online and Offline Channels in Retail: The Impact of Sharing Reliable Inventory Availability Information”. The paper finds that implementing Buy-Online, Pickup-in-Store (BOPS) decreases online sales but increases in-store sales and traffic. This effect arises from two phenomena: cross-selling, where customers purchasing through BOPS will buy additional items in-store, and channel shift, where customers transition from online to in-store purchasing, reflecting a “research online, purchase offline” behavior. The paper underscores the importance of understanding omnichannel retail strategies and their nuanced impact on different sales channels.

The study also indicates that areas in which stores offer the option to buy online and pick up in-store have observed an increase in online shopping-cart abandonment. This phenomenon is attributed to customers preferring to ensure the availability of products online before making in-store purchases. Essentially, consumers use the online platform to verify product availability, and once confirmed, they visit the store to complete their purchase. This behavior highlights how the online channel can function as a tool to facilitate informed, in-person buying decisions —a finding well-supported by the study’s comprehensive validation.

A different study (“The Value of Rapid Delivery in Online Retailing”), which demonstrates another causal pathway, shows that establishing a warehouse nearby influences online ordering patterns significantly; primarily by improving shipping speed. The paper’s main finding is that when a major U.S. apparel retailer opened a new distribution center, which reduced delivery times, they saw an average revenue increase of 4% from customers in the affected area. This revenue increase was primarily due to customers placing orders more frequently and purchasing more expensive items. Additionally, the study found that the new distribution center improved net profit by 2.2% due to increased sales margins and reduced shipping costs, highlighting the economic value of faster delivery in online retail. While the paper focused on a distribution center, as more retailers ship from their local stores, we will see more of this phenomenon.

But … despite the strategic advantages of omnichannel retailing, its impact varies across different sectors and companies. Warby Parker, often cited as the exemplar of D2C (Direct-to-Consumer) omnichannel success, illustrates a sophisticated application of this strategy. However, even with Warby Parker’s innovative approach, its stock price hasn’t reached the levels of other retailers, highlighting the challenges and limitations within the retail sector.

This complexity underscores the diverse nature of retail. It suggests that while omnichannel strategies offer significant benefits, they represent just one part of a broader retail landscape with multiple facets and outcomes worth exploring.

To try to help and characterize which products fit better into each model, The paper “The Store Is Dead, Long Live the Store” explores the evolution of retail from traditional brick-and-mortar stores to a blend of online and offline experiences, emphasizing the showroom model. It highlights how offline-first retailers transform stores into experience centers and reduce inventory, while online-first brands benefit from physical showrooms that enhance customer engagement and sales. The paper uses data from companies like Bonobos and Warby Parker to show that physical experience can supercharge customer value, leading to higher sales volumes and fewer returns.

While I appreciate the concept of this matrix, it’s evident that the physical store remains vibrant and significant beyond merely enhancing the online shopping experience. It plays a unique role within the complex fabric of consumer preferences, indicating that the physical retail space has a dynamic and standalone value in the shopping ecosystem.

First Principle Thinking

The current network of stores and warehouses we see has evolved over time within the existing retail environment. But what if we were to redesign the entire system from scratch?

First principle thinking involves persistently questioning the rationale behind decisions.

For example, which products make sense to shop in person? Which ones are easier to ship from a centralized location? Why do people shop in person, and would it still be the best option if we redesigned everything from the ground up?

For products that are not urgent, and shipping them is more cost-effective, it makes sense to ship them from a centralized location. However, for bulky items, with high shipping costs, which are also more likely to be damaged, it would make sense to pick them up in-store even if bought online.

Similarly, people’s shopping preferences vary. For example, shoes are something we usually all want to try before we buy. But what if you’re buying the Adidas ADIZERO Adios Pro Evo 1, which isn’t available in any store? Especially for running shoes, I tend to trust the reviews on Reddit more than in-store advice based on positive experiences with recommendations from the people on Reddit. This may seem unusual, but it illustrates the personal aspect of trusting information sources.

The diverse ways people access, and trust information make the strategic use of retail assets more complicated than it seems. As preferences vary widely, maintaining a variety of channels, including pickup and delivery, becomes essential.

However, implementing such a strategy is intricate —using a high-cost retail location on Madison Avenue primarily for shipping purposes is less efficient (or cost-effective) than utilizing a location in New Jersey for shipping to customers in Manhattan, despite any potential inventory control concerns.

Nevertheless, questioning our current practices and the underlying objectives of retail strategies offers an opportunity to reimagine retail as we know it.

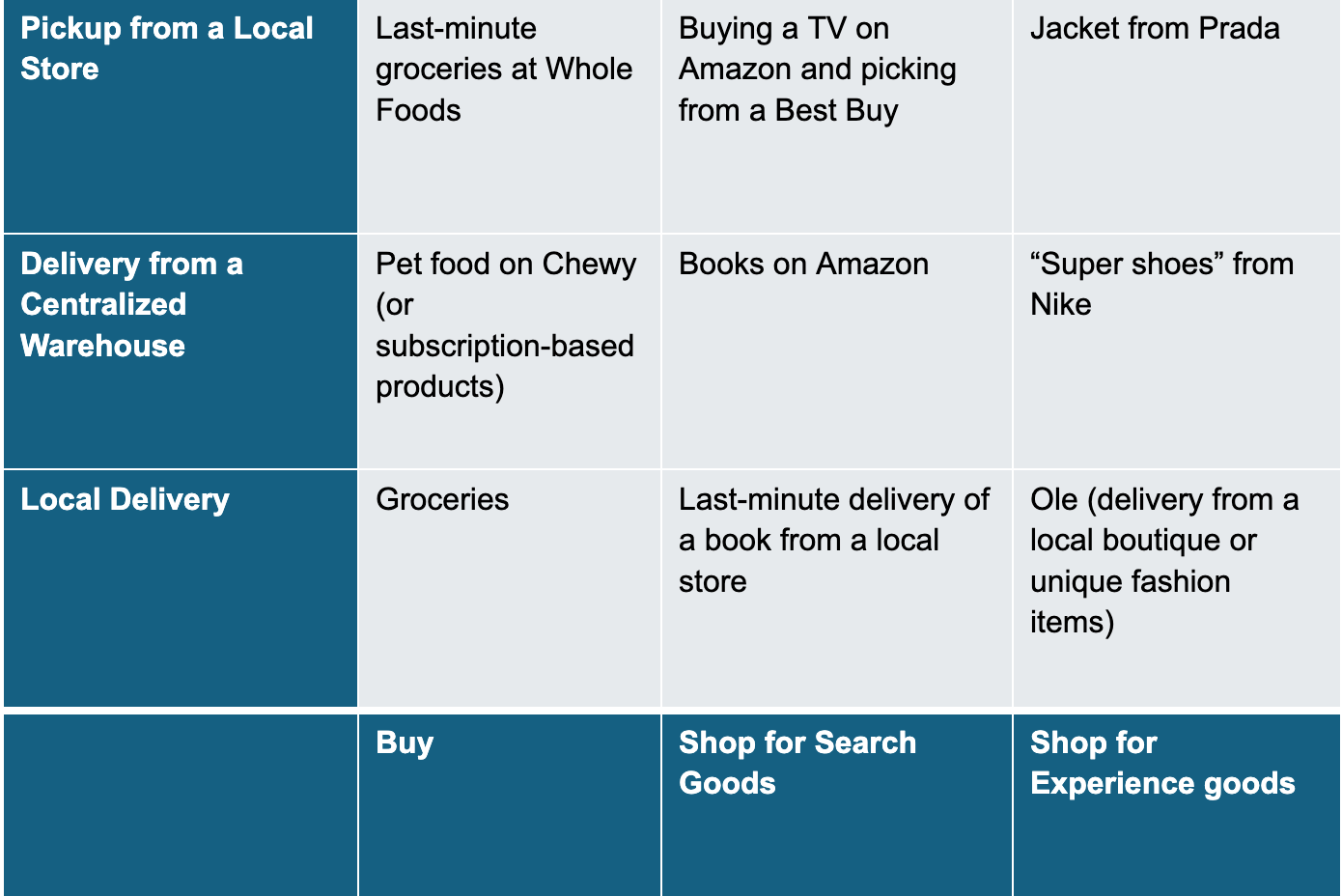

So, my first attempt to reconcile the issues above and imagine the network of operations needed to address various consumer buying behaviors is as follows:

Three Consumer-Buying Patterns

Let me begin by describing the three ways I believe consumers make decisions.

Using a concept inspired by Alex Torrey, the CEO of The Rounds, there are some products that we simply “buy” without putting in much thought (e.g., bottled water or toilet paper). In these cases, the decision process is straightforward and quick. We may have experimented with a few options, but once we settled on the products we like, we don’t continuously shop for better options.

For other products, the buying process involves gathering information, considering options, and valuing opinions from various sources. These products are items we “shop” for and require complex decision-making.

I also distinguish the “shop” items between two categories of goods: search goods and experience goods. Search goods are those for which consumers can determine quality and suitability by gathering information before purchase, often through reviews or product specifications. Experience goods on the other hand, require personal trial or experience to assess their quality and suitability, as their characteristics can only be fully understood with direct interaction or use.

Selecting a book, especially on niche topics for instance, is not easier when physically browsing in a Barnes & Noble store. In such cases, online resources that allow for targeted searches and review access, offer more efficient ways to gather what is needed to make informed decisions. For an item such as pants, on the other hand, online resources may not be enough to make the best choice.

Each of these patterns also brings other dimensions of consumer preferences and criteria.

When we “buy,” our main criterion is cost and sometimes speed (as a proxy for convenience). These items tend to be commoditized, meaning that if they aren’t available from one brand, we can choose another. Variety is not important as these products have similar characteristics.

But when we “shop” for “search goods,” variety is critical. We need to have enough options to find “the right product,” which varies from customer to customer since each person has their own unique preferences. While cost is always a criterion, our final decision is not based on that.

Finally, for “experience goods,” the most critical criterion is availability. If an item is not available, we can’t try or use it, and therefore, we won’t buy it. Cost and variety are less of a concern (albeit cost is always part of the equation).

Three Delivery Models

Each delivery method offers a different experience and covers different customer needs.

Local delivery offers the fastest option (and can be the cheapest with enough density), but it cannot offer variety. Shipping from a centralized warehouse or fulfillment center (e.g., a dark store) offers superior variety (due to inventory pooling), but it doesn’t usually offer speed, and the cost depends on product weight or dimensions, and shipping complexity. Finally, In-store Pickup is limited in terms of variety and cost (remember the trade-off curves above), but it can allow customers to “try before they buy.”

As we can see, all stores will evolve to fulfill a dual role (no pun): functioning as traditional retail spaces and local distribution centers. This transformation aims to meet consumer demands for various products alongside an increasing preference for convenience and cost-effectiveness. Walmart has already experienced that as they initially tried replicating the Amazon warehouse system for its walmart.com channel. It took it some time, but ultimately, the company understood that its main advantage was its existing distribution system and brick-and-mortar locations. Currently, Walmart fulfills 50% of online orders from its stores.

One Person’s Search is Another Person’s Experience

Looking at the three-by-three matrix, we realize that the cells on the diagonal are the ones that are entirely “aligned” in terms of matching consumer preferences and the best operations to deliver them. So even in a system designed from scratch, I believe there is room for the other models.

The essence of my argument is that what constitutes a search good (that requires external opinions) for one person, like shoes for me, may be an experience good (requiring a try-on) for another. Reality dictates that even certain search goods must be tried, hence the importance of flexible shipping from central locations, easy returns to local outlets, and the option to exchange sizes and potentially replace them. This adaptability, including expedited shipping to guarantee the shoe is received before the next race, ensures the continuous relevance of all three options in retail strategy.

The same is true for products. For example, while we think of books as primarily pre-mediated decisions with no urgency in receiving or seeing what it looks like, this isn’t always the case: Many times, we need to assess the book’s physical size if, for example we plan to take it on a flight.

The key takeaway is that the assumption of products being strictly categorized as search or experience goods doesn’t hold universally.

The integration of online and physical retail suggests that while brick-and-mortar stores will continue to serve a crucial role for certain consumers, the online shopping model will remain a preferred option for many. However, the traditional in-person shopping experience, characterized by a limited selection and expensive real estate, will be increasingly seen as unsustainable as a standalone option, even if it has a reprise in the post-Covid era. This evolution underscores the necessity for retail models to adapt, blending the strengths of both physical and digital realms to meet diverse consumer preferences effectively.

The evolving landscape of retail suggests that the journey toward integrating online, and offline channels is just starting, challenging the notion of a “retail apocalypse.” People’s preference for in-person shopping remains strong, indicating no need to fully revert to traditional retail models or rely solely on costly strategies like drop shipping. The future lies in utilizing retail spaces intelligently, such as leveraging them for efficient shipping, which underscores the importance of a balanced, omnichannel approach that adapts to changing consumer behaviors.

In a world where the term “retail apocalypse” was just a fancy way of saying “I prefer shopping for running shoes in my pajamas,” the real race is between clicking ‘add to cart’ and sprinting through the aisles.

So, may the best shopper win!

Really enjoyed this one!