If you follow the news, you’ve probably read the many articles written about Southwest Airlines’ meltdown during the days around Christmas:

“Southwest canceled 2,677 flights, or 65% of its scheduled Tuesday departures, according to data from FlightAware. The airline said Monday its reduced schedule would extend at least until Thursday. The carrier has canceled close to 11,000 flights since last Thursday as it has struggled to stabilize operations hampered amid the wintry weather.”

In this case, a picture is worth 1,000 canceled flights:

So the actual event was clearly weather-related, with the bomb cyclone, but other airlines which were subject to similar weather recovered fairly quickly, as we can see above.

Why is SW’s Meltdown so Shocking?

For a long time, Southwest was the darling of the business world, enjoying financial success. Even if you invested money in United, Delta, or the S&P500 40 years ago, you still wouldn’t come close to an investment similar to that of Southwest Airlines.

It was also the center of a seminal article from the 90s, What Is Strategy? by Michael Porter. The article discusses the unique set of activities that made it difficult to copy and compete against Southwest Airlines.

Activities such as:

Flying Point-to-Point rather than utilizing the more common hub and spoke system.

Utilizing one type of plane, thus allowing the airline to have pilots ready to operate any flight: “At Southwest, we only operate Boeing 737s, and our Pilots are highly trained and experienced at flying the aircraft.” These activities also included their bags-fly-free policy and the fact that there were no assigned seats, both of which would expedite the boarding process —essential for on-time departure. Finally, the airline avoided bigger and more crowded airports, and leaned toward secondary airports (such as Chicago Midway, rather than O’Hare).

These activities allowed Southwest Airlines to deliver better cost and on-time performance than all the other airlines, but the tradeoff was a limited set of origins and destinations. As the airline expanded, some of these activities were compromised. There are not that many small airports that serve major metropolitan areas, and this resulted in worse on-time performance and difficulty to maintain the low costs.

And indeed, the airline suffered a decline in its on-time percentage:

But they’re doing much better overall in terms of on-time performance than most other airlines, even on their “off year”:

What makes this meltdown shocking is the fact that many of these “activities” described above were meant to help the airline achieve this on-time performance and withstand flight disruptions.

For example, flying point-to-point meant that issues in the East Coast usually didn’t affect the other parts of their network that much, as most flights avoided the major hubs.

While living in Chicago a few years ago, I experienced a similar disruption with American Airlines. Due to wiring issues, many of its planes remained grounded for several hours. I was set to take off from Chicago to St Louis, but the only pilot that could fly our type of plane was still in Washington, DC. It was 8 pm, we were provided with a minute-by-minute description of where the pilot was (at the gate in DC, boarding, landing, running on the tarmac), and we finally took off from Chicago at midnight. On the way back, AA booked me on a Southwest Airlines flight; my only experience with Southwest Airlines to date. The likelihood of something similar happening at Southwest is smaller. If there’s a plane and a pilot, they’re ready to go.

Even the fact that they didn’t charge for luggage helped it be on time, since it reduces the incentive to only bring carry-ons. If there’s one inefficient way of loading luggage, it’s by passengers themselves, many of whom are in group 5 or group 9, and still believe there will be sufficient space for them… you know who you are.

So, one type of plane, limited network of P2P flights, flying through smaller airports, all of these policies should have helped better absorb the weather shock. So what happened?

Any claim for one answer is going to be too simplistic.

You can’t Hedge Against all Risks at Once

But I would argue that just because a network is built to deal with one type of shock, doesn’t mean it’s also built to deal with all types of shocks.

Let’s look at Southwest’s network:

It’s a complex web of arcs. Now, let’s compare it with United:

The hub and spoke patterns are clearly visible (located in Newark, Houston, etc).

The point-to-point system is great when shocks are independent of each other. Bad weather in San Jose, doesn’t affect the East Coast’s operations. In the hub and spoke system, disruptions in Newark (a hub) immediately affect the entire network since flights arriving at Newark can’t reach Newark, which means they can’t depart either.

However, I would argue that the point-to-point system, paired with a specific route for each plane (where they don’t just fly back and forth, but rather follow a circular route) is not suitable for a situation of correlated shocks, such as simultaneous bad weather in Seattle, Buffalo, Chicago, and Denver. For such situations, a hub and spoke system seems better, since there are more resources located in the “pooled” hubs, allowing the airline to recalibrate quicker. In particular, a fully centralized system (which hub and spoke is closer to) that can pool the issues and re-route people based on where they need to go, would be better in a situation like that, since passengers fly through a hub anyway.

This is somewhat related to the fact that many blame the software used to deal with these disruptions. I would argue that, most likely, the software system is more suitable for small disruptions, that a small number of perturbations can solve, and not for system-wide issues. The software might be antiquated, but again, I don’t think other airlines’ software are much more sophisticated (being a customer of most other major airlines). It must be deeper than that.

It’s much easier to reboot the system when you have most of your employees, planes, and routes go through a small number of locations.

On the other hand, the activities that allowed the airline to keep the costs low, particularly the high utilization of its planes and seats, may have contributed to the additional recovery time. As you can see in the graph (based on available data), the average daily block hours of Southwest were higher than other airlines (until they recently converged):

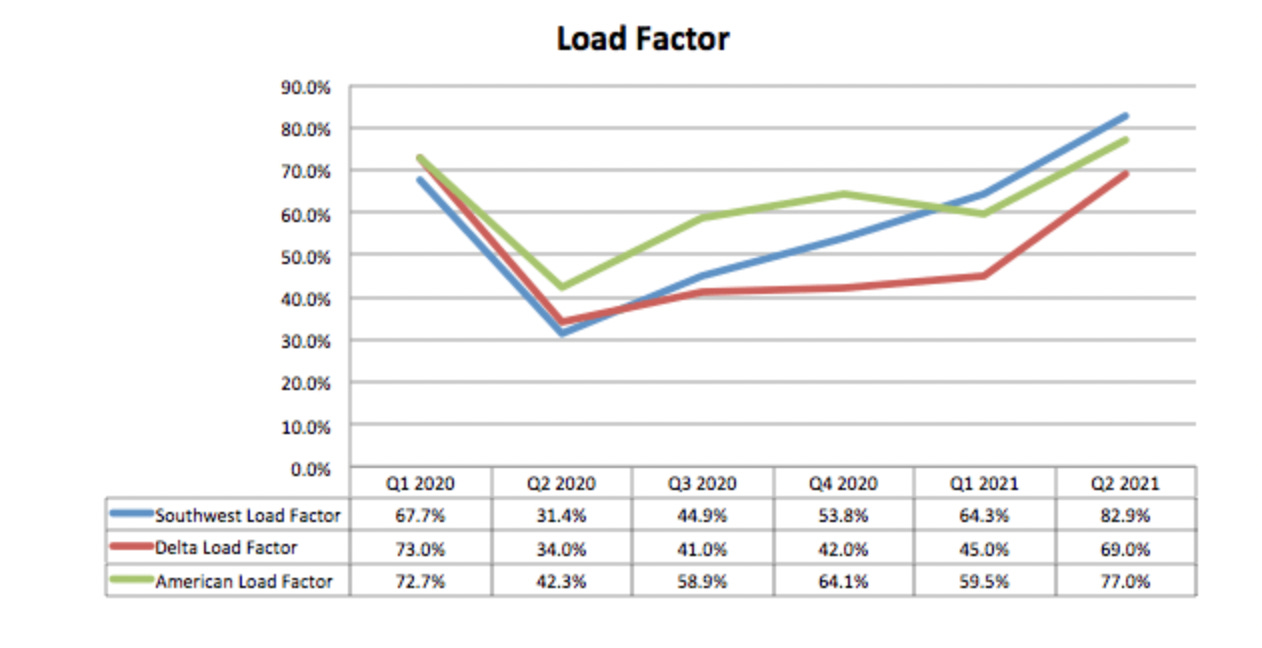

This is also true for its load factor, which is usually identical across airlines, but Southwest’s was faster to increase post COVID:

And while the load factor or high utilization may seem unrelated, they can explain why it takes longer for SW to recover: When the utilization and load factor are high, it’s hard to find empty seats and rebook flights that were a-priori full.

Finally, an interesting statistic is that Southwest consistently has more departures per aircraft, per day:

To achieve a similar number of available seat miles, Southwest operates its aircrafts more heavily in terms of utilization, seat utilization, and the number of departures (where, admittedly, the complexity lies).

All these factors together explain why other airlines had an easier time recovering: fewer moving pieces to deal with when the entire system is hit and shuts down.

There are also a few smaller issues that definitely contributed: Southwest is more concentrated in the US and has no partners to lean on, which leaves it more exposed to such issues. I am writing this post from the French Alps after a long day of skiing with the family. We flew here on Christmas day, two days after airlines were hit by the bad weather, but planes arrived from Geneva, and from London before that. United sent me an email in advance allowing me to rebook my flight, which fortunately, wasn’t necessary.

I hear people claim that airline consolidation caused this meltdown, but I don’t see this as the issue in this case. It’s true, the US airline industry is too concentrated, but one can argue that consolidation may be better for situations like this (not that we want to build the entire system to hedge just against a specific situation).

Finally, it’s easy to see how Southwest’s bags-fly-free policy absolutely backfired. The checked bags actually complicated everything, resulting in images like this:

Conclusion: No competitive advantage is long-lasting since firms are constantly forced to grow and put pressure on what brought them their initial success. No single solution hedges against all risks. For the risks you are not hedged against, think about how they can be mitigated when they happen. And finally, never check in your luggage … Never.

I was in a round about way saying that Southwest has in a way outgrown itself! It’s success actually caused the problem ! If your an employee , trying to get to a destination to start working, most flights are already full! Jump seats are taken! Other airlines have more open seats and more direct flights and Nickel and dime their customers! Not Southwest!

Gad, I loved reading the article. Appreciate the detailed analysis supported by strong premises. Thanks for sharing..