Subscribing to the Great Automation

Last week, Bloomberg had a great article on a new trend involving automation: Robots as a Service.

Robots and automation have gone through so many hype cycles that I’ve completely lost count.

In fact, in one of my favorite books, The Goal, the story begins with a manager on his way to a conference to share a success story about the installation of robots.

The two protagonists (the manager and a professor) meet at the airport where the professor asks whether these robots indeed present an improvement by asking three questions:

Are you selling more?

Are you carrying less inventory?

Did you fire anyone?

After the manager responds negatively to all three, the professor concludes that the robots are not a real improvement.

Over the years, the slow adoption of robots was justified by the fact that unless the task was highly specialized, robots failed the three questions.

So what has changed? Three factors:

Labor market tightening.

Technological improvement.

Business model innovation.

Labor Market Tightness

Let’s start with the obvious: we are in the midst of the Great Resignation with a limited labor force that also exhibits a reduced willingness to work for heavy industries, such as manufacturing and logistics, that require repetitive tasks or actions.

In a recent conversation with a person that owns hundreds of coffee shops around the world (I cannot disclose more), they admitted that the problem is the difficulty in finding people who want to work as Baristas, and the problem escalates further when you see them leave shortly after they have completed their training.

In another conversation with a logistics firm, the manager acknowledged that they are now forced to start compromising on their vetting process when looking for warehouse employees.

So the real challenge is not the higher wages, it’s the inability to find workers to fill these roles.

Under these new circumstances, for the third question, the professor asks in The Goal: there is no one to fire because there is no one to hire other than robots. And this is exactly what robots can do well: repetitive and well-specified jobs. Without enough employees or some automation, these firms won’t be able to meet demand and will lose sales.

Technology

The main issue with robots, and automation in general, has been that robots were only good in highly specialized jobs, and lacked the ability to be flexible.

I previously devoted an entire article to this topic, but the reality is simple: driven by advancements in a variety of areas, from visual detection to dexterity, robots have become more flexible over the last few years, allowing them to co-exist with humans.

As I mention in that article, every pandemic resulted in an increase in automation, primarily as it was a shock to the “system” requiring firms to re-evaluate their business operations.

Business Model

But the new feature in the Bloomberg article is the business model being introduced. Rather than acquiring the robots via upfront capital expenses, a firm pays the robot manufacturers (and owners) a subscription fee per hour of usage or per month. The model is called ‘Robots as a Service,’ and is, of course, inspired by the idea of SaaS (software as a service).

But let’s look at the benefits and risks for the two parties involved: the firm using ‘Robots as a Service’ (which we will refer to as Buyer) and the firm offering ‘Robots as a Service’ (which we will refer to as Vendor).

The Buyer

Let’s start with the Buyer. One customer in the Bloomberg article described some of the model’s benefits:

“That financial model is what led Thomson [Plastics Inc] to embrace automation. The company has robots on 27 of its 89 molding machines and plans to add more. It can’t afford to purchase the robots, which can cost $125,000 each, says Chief Executive Officer Steve Dyer. Instead, Thomson pays for the installed machines by the hour, at a cost that’s less than hiring a human employee–if one could be found, he says. ‘We just don’t have the margins to generate the kind of capital necessary to go out and make these broad, sweeping investments,’ he says. ‘I’m paying $10 to $12 an hour for a robot that is replacing a position that I was paying $15 to $18 plus fringe benefits.’”

The first benefit is clear: rather than spending $125K to install a robot, this firm prefers to pay $12 per hour, making its cash flow more palatable and reducing the financial risks it is exposed to.

Another benefit is that, since technology will probably change in the next few years, the Buyer avoids paying a large amount of money to own a potentially outdated, or even worse, obsolete robot after a few years.

While the following example doesn’t describe the exact same situation, it serves to help understand the statement above a little better. A few years ago, and after owning a car for 15 years, I decided to start leasing. The main reason was not financial but rather the fact that technology has been changing rapidly over the last years both in terms of safety and self-driving capabilities, and electrification. Not knowing how fast these advancements will mature, I opted for a less restrictive solution by leasing a different car every few years instead of buying and selling every time a more advanced model came out.

But while the market for used cars is rather liquid (so buying and selling is doable in favorable market conditions), this is hardly the case for robots. So the ‘robots as a service’ option allows the Buyer to transition to automation, without having to bet on technology.

But there are additional benefits: A subscription model allows the Buyer to scale their consumption of automation up or down as their needs change.

Finally, the Buyer is purchasing a complete service rather than a product. Rios Robotics, a VC-backed firm that is mentioned in the article, charges a flat monthly fee that includes installation, initial programming, regular software updates, reprogramming as needed, maintenance, and 24/7 monitoring. In other words, through this new business model, one of the main issues with robots, i.e., the fact that they require additional labor and work to maintain and reprogram, is resolved.

Note that this is not a discussion of the merits of robots, but rather the benefits of the model for those considering automation, but are somewhat hesitant for various, valid reasons.

What are the risks?

$125K vs $12 per hour. While this may seem obvious at first glance, we must look at the time period first. Assuming the $12 only refers to hours of operation, and the operating period is 20-25 working days of 12-hour shifts, we have a monthly fee of $3K to $4K per unit. Even at $5K per month, the Buyer would need to rent for more than 2 years to break even. In other words, I think the risk is rather low.

The bigger risk is relying on a Service Level Agreement from a firm that may or may not be able to offer proper support: machines break and may cause damage. This risk is evident in any type of outsourcing, but even more so here, as these robots operate on the firm’s “shop floor.”

In addition, the Buyer is making changes to their fulfillment center or production line to integrate these robots. But as the Vendor evolves, they have less control over how things are going to look and operate. For example, will the Vendor continue to operate and support these robots? Will the features of these robots remain the same or will they change?

When Zoom decided to replace the single-click “raise hand” feature with a two-step process (meaningless for most people, but a huge difference in a class environment), as professors, we easily could accommodate such a change by giving students more time to raise their hands when needed. This is not the case when it comes to physical robots and automation. In other words, the Buyer is taking a risk by assuming that the Vendor will continue to support and develop the robots being used. Integration is never costless.

The Vendor

Let’s take a look at the Vendor: the firm offering ‘Robots as a Service.’

As a robotics firm that has to decide between selling your robots and selling a service, the upside of the latter is clear: the sales cycle is much shorter since it’s easier to articulate the value proposition and mitigate the customers’ risks (from potentially obsolete technology to limited ROI). A short time-to-market, which is key for any startup, is going to be a huge advantage compared to traditional business models.

The second advantage is that you are moving from selling a product, which is usually hard to forecast, to selling a service that has a recurrent revenue stream, making it much easier to predict cash flows. The reason it’s easier to forecast revenues in this case is that switching cost is not trivial for customers (given the changes they will need to make to their workflow). Furthermore, since the relationship requires the Vendor to continue and maintain the robots already deployed, it creates opportunities to upsell and upgrade equipment in a much more seamless manner.

As with all “Something as a Service” options (from the cloud and software to ride-sharing), and assuming you can reuse these robots, it’s possible to pool demand from multiple industries and geographical locations to reduce risks. Of course, there are systemic risks that are correlated. For example, a recession will hit multiple firms simultaneously, leaving the Vendor in deeper trouble, but idiosyncratic shocks should be absorbed better in such a model.

Finally, given that these solutions include both hardware and software components, firms can be more agile in product development since they acquire very intimate and detailed usage data to support roadmap decisions.

So what’s the downside?

First and foremost: financial risk. As the Vendor you are bearing the risk of the technology as well as the financial risk since a larger, upfront capital investment is required to build the robot fleet. These assets will need to be carried in your books, making your balance sheet much less appetizing than most SaaS firms or robotics OEM’s. So for a traditional robotics firm, moving to the Robots-as-a-Service model will have a significant impact on the financing and accounting practices.

Furthermore, Robots as a Service changes the customer’s expectations and the ways in which they pay for and engage your services as a supplier. In particular, contracts are going to be significantly more complex. Do you charge a monthly fee? Do you charge “power by the hour?” What's the minimum contract in terms of time? What’s the Service Level guarantee? How do you monitor remotely? What about the risk of cyber-attacks? There is still much to figure out and define before this business model becomes more widespread.

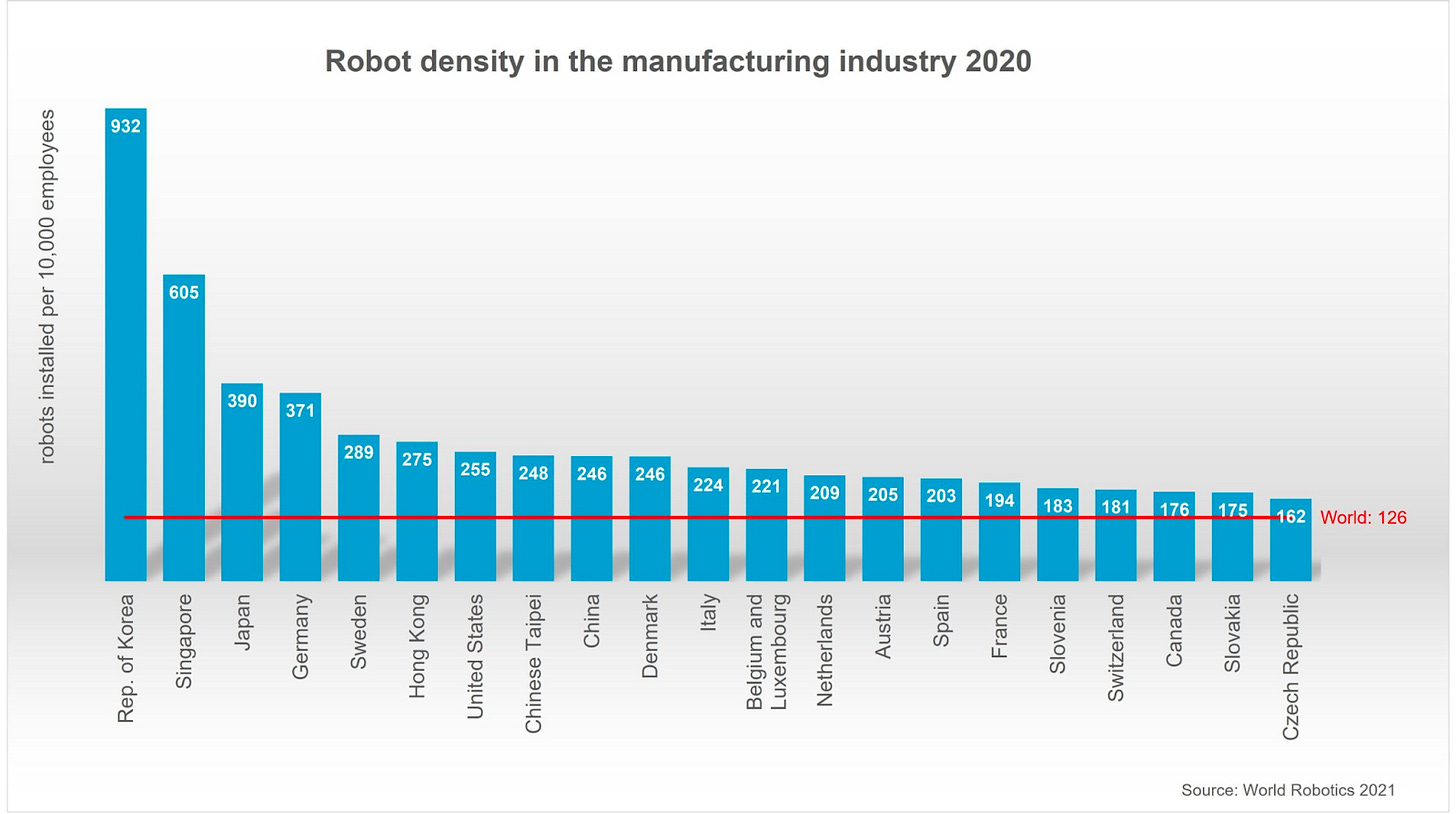

But for the right automation applications and the right scale, Robots-as-a-Service can be the simplest and fastest way to “buy” and deploy automation. Given, primarily, how much the world is lagging in the deployment of this technology, this can be the change needed to ensure we finally settle on the plateau of productivity.

People still think that robotization is something similar to the enemy. They, or us, but there's no room for both of us. However, I'm starting to consider the problem of derobotization. Unless you have the control of your product and can manufacture large series of units, most of companies don't want robots, because they need to be flexible and invest much time on reprogramming them for different tasks. But is (de)robotization a safe choice for the future of the company or a national economy?

An additional benefit: for the tasks that are being done by Robots and paid by the hour, the Buyer has maximum flexibility to run from only a few hours/day to 24/7 operations without paying overtime or having idle (or furloughed) human workers.