Over the last few days, we witnessed an interesting development in the healthy food arena. Sweetgreen, known for catering to customers who prioritize healthy eating and can afford to splurge on a salad as if it’s a fine dining experience, made an intriguing announcement: they’re launching steak as part of their protein offerings.

While initially aiming to be profitable by 2024, the firm is not quite there yet. It shows positive gross margins, but profitability is still elusive.

So why did their stock have one of the largest single-day jumps on Friday morning (43% to a high of $33.75)?

What’s behind this surge and the significant stock improvement since the beginning of the year, nearly tripling in price?

While this isn’t a financial valuation newsletter, I believe there are many questions related to our interest in operations and scaling. So, let’s delve deeper.

Using my SCALE framework, we’ll try to understand Sweetgreen in general, but also more specifically, the impact of such an announcement.

Scalability

As a reminder, to determine if a firm is scalable in the context of my framework, we look at whether revenues grow faster than costs. For a firm that’s growing but is not yet profitable, it’s quite common for both revenues and costs to increase. What matters is the pace at which each metric grows.

For the mathematically inclined, we require that the second derivative of revenue is higher than the second derivative of cost. Not just the first derivative.

For those who are a little rusty in math: We want the rate of revenue growth to increase.

For example, if the first customer brings in $1 and costs $0.80 to serve, and the same is also true for the 100th customer, our curve is linear, meaning margins remain fixed. Scaling is a situation where every incremental customer brings a higher revenue or is less costly to serve than the previous customer.

And this is the case with Sweetgreen —the firm is not yet profitable, but its revenues are clearly growing faster than its costs.

And the second derivative:

Looking at the graphs, it may seem there’s not much of a difference in terms of slope, and while the second derivative of revenue is higher, it’s not significantly higher.

The next graph is more positive, and specifically for operating expenses.

The difference in the second derivative is more noticeable here.

The second derivative is negative for revenues and costs toward 2023, and to put this in context, a negative second derivative indicates that the first derivative (which represents the rate of change) is decreasing.

In practical terms:

1. For Revenues: A negative second derivative suggests that the rate at which revenues increase is slowing down. If revenues were initially growing rapidly, a negative second derivative implies that the growth rate is tapering off. If revenues were declining, a negative second derivative implies that the decline is accelerating.

2. For Operating Expenses: A negative second derivative suggests that the rate at which operating expenses increase is slowing down. If operating expenses initially rose quickly, a negative second derivative indicates that this rise is slowing down. Conversely, if operating expenses decreased, a negative second derivative implies that the decrease is accelerating.

Overall, it seems Sweetgreen can convert scale into a potential long-term competitive advantage. Once the firm becomes profitable, it will experience further margin expansion, making it increasingly difficult for competitors to enter the market. The firm is pressured to grow to justify its valuation, so it’s good to see that it’s not growing for the sake of growth but is disciplined in how it improves its unit economics.

What Are the Scalability Drivers?

To better understand what drives scalability for a restaurant chain, we must examine two different levels: the restaurant and the chain.

During one of its earning calls, Sweetgreen stated that about 80% of labor cost is fixed, and 20% is variable. Real estate costs are also fixed while ingredients are variable, and given the quality of ingredients, we can’t expect significant scale effects.

Therefore, the higher the volume Sweetgreen restaurants can handle, the higher the profit at each location.

This explains why there’s so much pressure to increase sales volume. By introducing Steak, the firm can utilize its fixed assets (physical stores) and employees more effectively —they can increase sales by attracting more customers, especially for dinner, where people typically prefer more than a salad. Fixed costs spread over a larger number of sales will enhance profitability.

So at the restaurant level, we can see significant economies of scale. But what about at the corporate level?

As a chain, Sweetgreen can and should grow by adding more locations. The firm is currently operating close to 230 locations and aims to expand to approximately 1,000 locations.

There are supply chain capabilities and the potential for creating density with multiple commissaries or centralized kitchens, but the effect isn’t as significant as what we see per store. The firm also has an app and some technology, but the cost doesn’t seem too high —the app is quite simple, and the point of sale is nothing too exciting. While there are some benefits of spreading these costs across more orders, I don’t see that as an important driver.

The firm doesn’t have other drivers such as network effects, a learning curve, or switching costs (their customers are loyal), so most of the economies of scale are found at the store level.

Efficiency

Efficiency is mainly about whether a firm has a predictable path to profitability, and by predictable, I mean whether we can understand the relationship between the firm’s operational metrics and financial outcomes well enough.

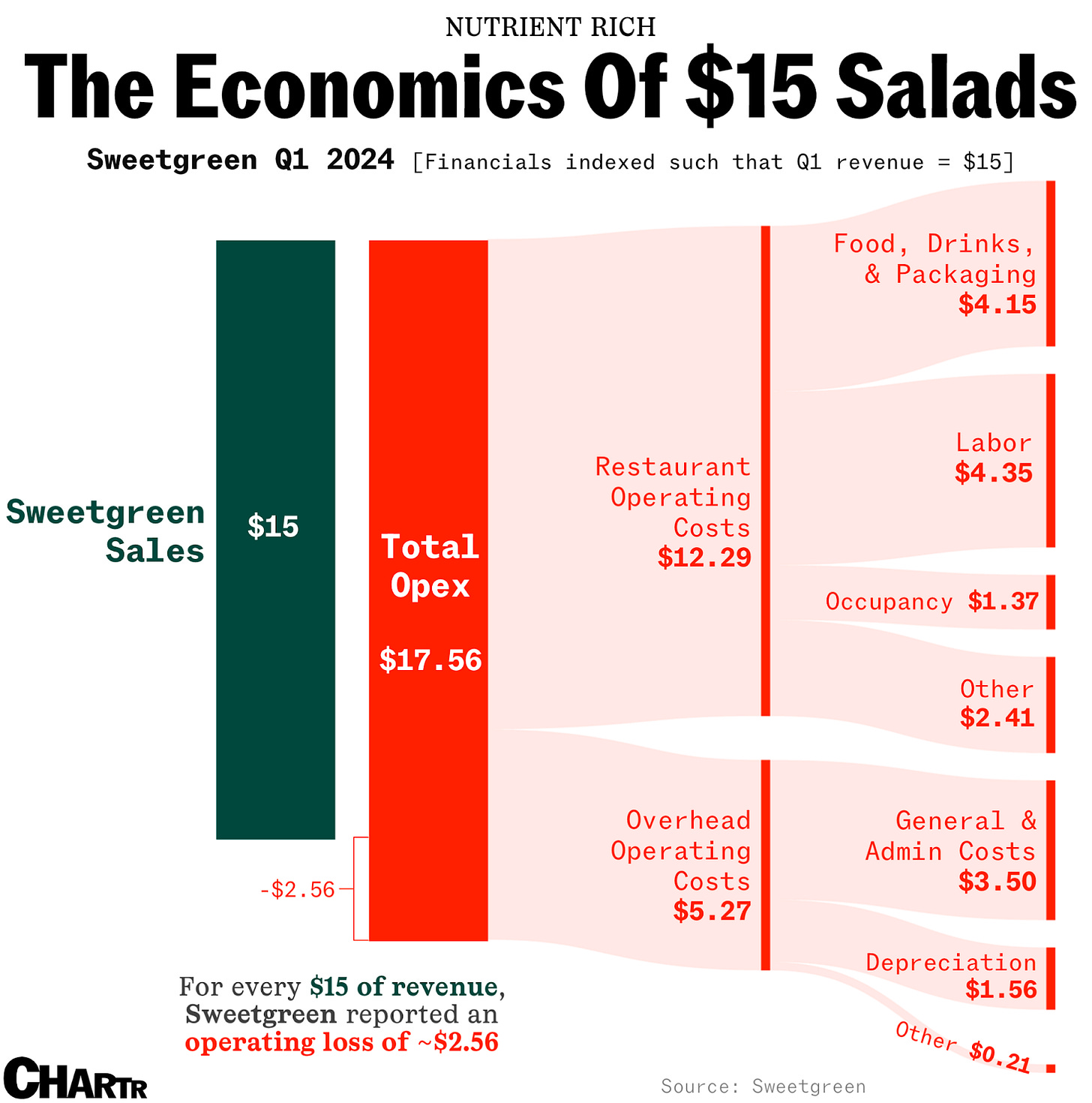

For Sweetgreen, the economics is quite simple, as evident by the following infographics:

The metrics to determine the path are quite simple:

1. Number of orders fulfilled per hour per store: The current rate is 27.7 orders per hour, with profitability achieved at around 36 orders per hour.

2. Average order value: The current average is $24 per order. Profitability is projected at $31 per order.

3. Number of stores: Sweetgreen aims to exceed 885 stores to achieve profitability, with a target of 1,000 stores by 2030.

What does the firm do to improve these metrics?

Apart from adding steak to increase both volume and average order value, Sweetgreen is taking significant steps to enhance its profitability through innovative technology. In 2021, the company acquired the Infinite Kitchen technology by purchasing the robotics company Spyce.

The Infinite Kitchen, a robotic system for food preparation, can produce up to 500 bowls per hour. Sweetgreen currently operates two restaurants equipped with the automated salad bar system (Chicago and California) and plans to expand this initiative by opening seven more restaurants featuring this automated system in the coming year. While the system requires an additional investment of $450 to $550K per location compared to standard builds, it is expected to improve efficiency and profitability significantly.

The Infinite Kitchen has demonstrated higher throughput and better margins than traditional stores, both because there is no labor used, but also because people ordered more expensive options (10% increase in average order value).

Sweetgreen has also been improving operations by reducing employee turnover and enhancing efficiency, by handling some tasks off-site, for example. Over time, these improvements and the addition of higher-priced items have allowed the firm to increase its revenue growth rate faster than its cost growth rate. This analysis considers both time and quantity, highlighting the firm’s main idea of achieving profitability through scaling operations efficiently.

In conclusion, Sweetgreen demonstrates a clear path to profitability through its strategic focus on scalability, technology innovation, and operational efficiency.

Alignment

The next point in the growth phase pertains to the firm’s readiness in terms of its operating system.

Sweetgreen has strategically aligned its business model to cater to health-conscious consumers, particularly in urban and suburban areas. This alignment is evident in its operations, from product offerings to supply chain management and customer engagement.

The firm has carved out a strong niche in the fast-casual restaurant industry by offering quick, convenient, but high-quality food options. The primary products—salads and warm bowls—appeal to young, health-conscious, high-income consumers who prioritize nutritious meals but lack the time to make them.

Employing a user-friendly digital platform that simplifies ordering and personalizes customer interactions based on past purchases, Sweetgreen’s operational processes are designed to enhance both customer experience and operational efficiency.

The company’s supply chain is another critical component of its alignment strategy. Sweetgreen emphasizes sourcing fresh, locally grown ingredients, which supports its promise of quality and sustainability. This regional supply chain approach allows Sweetgreen to offer a diverse and seasonal menu, aligning with customer preferences for variety and transparency in food sourcing. However, managing such a complex supply chain can be challenging and costly, particularly as the company expands into new markets.

Sweetgreen differentiates itself by focusing on health and sustainability. While competitors may offer similar speed and convenience, Sweetgreen’s commitment to organic, locally sourced ingredients sets it apart. This value proposition appeals to its niche —customers who value these attributes and are willing to pay a premium.

Sweetgreen’s main processes, including ingredient preparation and order fulfillment, are designed to support its high-quality standards and customer service. The company’s investment in technology, such as the Infinite Kitchen setup, further enhances its operational efficiency by reducing labor costs and streamlining the order assembly process. This technological integration aligns well with Sweetgreen’s goal of providing fast and reliable service while maintaining product quality.

Despite these strengths, Sweetgreen faces some misalignment issues as it scales. For instance, the introduction of new menu items and expansion into suburban markets has added complexity to its operations. The new Protein Plate menu, aimed at attracting dinner customers, complicates the in-store fulfillment process, which can disrupt the efficiency of the established workflow for salads and bowls.

The interesting aspect of adding steak in terms of their value proposition is the attempt to attract more men (who are easily lured by the simple idea of steak) and dinner options (which is also a congested area).

To do so, the firm must develop a slightly different set of suppliers with different requirements and process these items differently.

Additionally, Sweetgreen must navigate more delicate issues in terms of sustainability. In general, people believe that chicken has a limited environmental impact. In contrast, beef is known to have a significantly larger environmental impact. This presents a challenge in aligning with sustainability claims.

The second issue is the different types of competition they will face as they move more into the dinner market, which involves different dynamics and competitors compared to lunch. Lunch is often viewed as a time for quick, on-the-go meals, often eaten while working at your desk. So, is a salad or salad-type meal even a viable dinner option? I’m not sure.

Firms that have attempted similar transitions like McDonald’s with its breakfast options, managed to spread the cost of having employees in place earlier by expanding the share of the wallet of customers who already visit frequently.

The main issue for Sweetgreen is its high prices. Adding dinner options while maintaining the same level of quality means using more expensive ingredients. There’s a big question about whether this aligns with their overall strategy and whether it’ll be successful. Additionally, the ambiance of Sweetgreen locations might not be conducive to dinner. Many are seen as casual, quick-stop places. Salads generally aren’t considered shareable, which can be a drawback for family dinners.

One of the challenges that Sweetgreen faces, like other fast-casual and quick-service restaurants, is maintaining a consistent shrink (inventory loss) management process as they scale. The issue here is magnified as the firm must procure more expensive ingredients to cater to its new target in terms of customer base and meal time. At least initially, I expect the shrinkage and the associated costs to increase.

In conclusion, Sweetgreen’s alignment of its strategy, processes, and market fit has been a key driver of its success in the fast-casual restaurant industry. However, as the company continues to scale, it must address operational complexities to maintain its alignment and achieve sustainable growth. It will be interesting to see whether there will be pushback from customers on the less sustainable practices and whether indeed it’ll be viewed as a suitable dining place.

Constraints

We’ve discussed the firm’s main tailwinds and the steps it needs to take to “tighten” them.

Let’s now consider the main headwinds:

In many ways, the firm doesn’t have real physical constraints. For example, it can acquire more robots, employees, and ingredients, which are expensive (and thus factor into efficiency), but they’re not real constraints on the firm’s ability to grow.

So, what’s the constraint?

The real constraint is whether there are enough U.S. locations to justify a $25 salad. While this might be feasible in cities like New York, San Francisco, Austin, and university towns, reaching 1,000 locations with this pricing strategy is less certain.

And here we can see how adding steak is a double-edged sword. While it helps attract more customers, it’s high-end. There’s a risk of sticker shock when people realize that it costs $26 to have a salad with steak, whereas they can potentially have an actual steak (with a salad on the side) for the same amount or less in several other locations.

Leadership and Human Limitations at Sweetgreen: Processes, Structure, and Culture

Assessing human limitations is always important, and Sweetgreen faces several, which impact its leadership, processes, structure, and culture. These “barriers” challenge its scalability and operational efficiency, particularly as it seeks to expand its market presence.

Processes: Sweetgreen’s processes are often strained by high staff turnover and the complexity of its operations. The company employs formalized procedures for sourcing ingredients, preparing food, and fulfilling orders, essential for maintaining consistency and quality. However, the high turnover rate hampers these processes, particularly among store employees. In 2019, the turnover rate was over 200%, and although it decreased to 131% in 2021, it remains one of the highest in the industry. This constant churn disrupts training, and increases the workload on the remaining staff, leading to inefficiencies and potential declines in service quality.

Structure: Sweetgreen operates with a functional organizational structure, which helps maintain cost efficiency and a consistent customer experience across its locations. Decision-making about menus and store layouts is centralized, ensuring uniformity and adherence to the brand’s core values. However, this centralized approach can be slow to respond to local market conditions and specific store needs. While general managers at the restaurant level are empowered to make hiring decisions and interact with staff and customers, the high turnover of managers—46% compared to the industry average of 33%—further complicates efforts to maintain efficient and effective store operations.

Culture: The culture at Sweetgreen emphasizes health, sustainability, and community engagement. The company promotes its values through various practices, such as daily team huddles known as “Sweetalks,” where general managers motivate their teams. These practices aim to foster a sense of purpose and passion among employees. However, the high turnover rates suggest that these cultural initiatives are not fully effective in retaining staff or reducing burnout caused by the demanding nature of the work.

In summary, while Sweetgreen’s leadership has established processes, structures, and cultural initiatives to support its growth and operational efficiency, significant human limitations remain. Addressing these issues through improved training and better retention strategies could help Sweetgreen achieve its scalability and profitability goals more effectively.

Bottom Line

Am I optimistic about this firm? Yes.

There are strong tailwinds: Customers like the product, and the value proposition is solid. There are clear economies of scale, particularly regarding the rate at which they’re getting close to profitability.

However, there are many open questions.

One significant concern is that the economies of scale are primarily experienced at the local level and not as much at the corporate or chain level. This suggests that there is a limit to how much can be achieved through scaling alone. There’s a limit to how much you can generate these advantages, but we’re still quite far from that limit.

Sweetgreen’s stock price is largely tied to its ability to reach 1,000 locations, and this is where my skepticism lies. Reaching this number will be quite challenging, given the firm’s specific value proposition. I don’t think there are enough locations in the U.S. that can accommodate the necessary sales volume at the price they charge, and changing this isn’t feasible since the price is part of their value proposition. Additionally, maintaining a somewhat local supply chain adds to the challenge.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. What do you think about Sweetgreen’s value proposition? Have you tried their offerings? If so, please comment below with your experiences and insights.

I really like this analysis! I am however less optimistic. $31 per order being the point of profitability is way too high for any place outside the Bay Area or NYC.

I think the other thing to be concerned with is how much harder it will be for Sweetgreen to appeal to the dinner crowd. This part is difficult for me to explain, but as someone who moved from NYC to a suburb in Colorado, there's a greater joy of eating dinner at a Shake Shack or a hole in the wall restaurant when you live in a big city culture. That feeling changes significantly when not in that culture. Every time we get salads at a salad place, it *feels* more depressing than getting a salad at a full service restaurant/bar even if the salad is better. Maybe that's just getting older as well, but that reason would make Sweetgreen's dinner prospects even worse.

I think they're going to struggle as much, if not more, than Shake Shack has with expansion.

I loved this letter - particularly the derivatives analysis. I wrote about sweetgreen in my substack last week, and agree that labor is one of their most costly obstacles to profitability - infinite kitchens will help but there is still a while for those to roll out. Didn’t know about the high turnover - super interesting. Love the letter!!!