Taxis and Uber: A Deal with the Devil?

Last week, the Wall Street Journal broke the news of an upcoming agreement between Uber and the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC), allowing Uber to list all taxis in NYC. Uber also stated that its final goal is to list every taxi in the world on its app by 2025.

This is a major change in a somewhat volatile industry that has not seen significant changes (at least on the mobility side) over the last 5-6 years beyond those imposed by external shocks such as COVID-19, or AB-5 and Prop 22.

The media was quick to describe the agreement as the end of Uber’s Kalanick era, as the former founder usually chose graphic language to describe his hate for taxis.

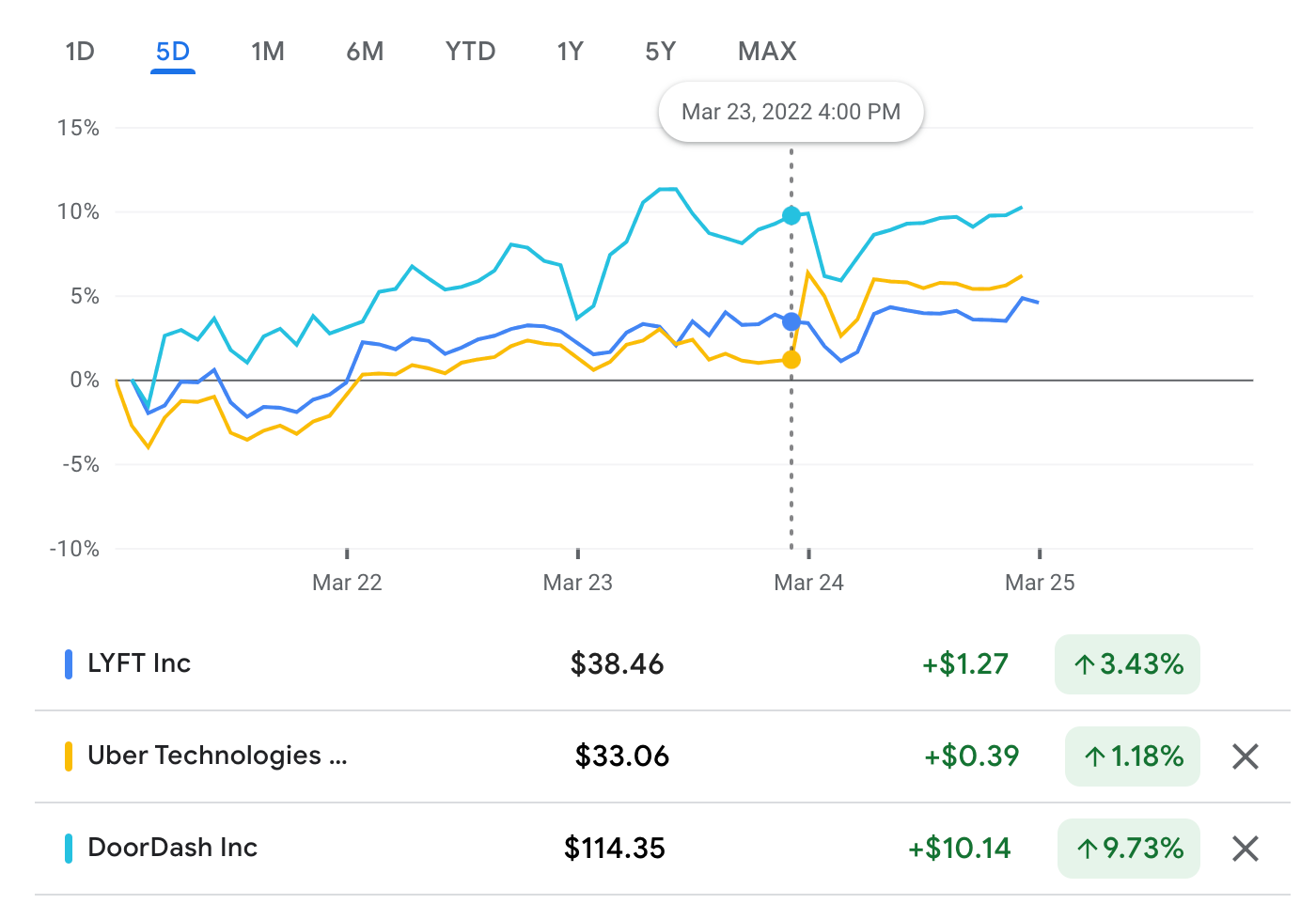

The markets were quick to reward Uber with a 5.5% increase in its stock prices.

At the same time, Lyft showed a significant drop, and there was an almost unnoticeable impact on DoorDash (which was already demonstrating an upward trend).

Since “the morning after,” the three stocks exhibited similar performance: an initial dip at the “opening bell” followed by a similar increase for all three stock prices, and maybe a slightly more pronounced increase for DoorDash. But this may just be noise.

Trying to assess the impact of this deal is actually harder than it seems. Who are the main winners and losers?

In order to assess that, we have to think about who the main stakeholders are:

Uber

Uber Drivers (Gig Workers at large)

Taxi Drivers

Consumers

The competition in mobility (Lyft)

The on-demand competition (DoorDash)

I will try to start with the obvious winners and losers, before delving into the impact on Uber, which I believe is not as obvious as it seems.

The Obvious Winners

Taxi Drivers: The definite winners

The main winners in this situation are clearly the taxi drivers, at least in the short run. When Uber first entered the market, it was devastating to taxi drivers. It is enough to look at the prices of taxi medallions in NY to understand the huge impact it had on them. From over one million dollars to $80K in a span of a few years:

In fact, as mentioned above, the founder of Uber, Travis Kalanick, used taxi drivers as Uber’s main target.

Under this agreement, taxi drivers will have more options since they can choose to accept an UberX ride at any point of time, in which case they most likely won’t be worse off than when they are acting as taxi drivers (although this seems debatable since some UberX rides may land them in less profitable places, I believe that it is a learning curve and that in time, they will learn to identify and avoid them).

The main benefit is that these drivers, which are often not allowed to pick up rides outside Manhattan, will be able to earn more by also utilizing UberX, rather than just being a taxi.

And finally, they will have access to Uber’s vast demand. As Ben Thompson likes to say (in a loose translation), supply likes to go where demand is, and demand is definitely with Uber.

Consumers

Another group that, in the short run, will benefit from this is us, meaning the consumers. We will enjoy lower prices and, potentially, lower waiting times.

Also, we will start avoiding one of the most inconvenient things in transportation: the act of physically hailing a cab in the street, as if we were back in the ’90s starring in an episode of Sex and the City, as well as having to remember to pay at the end of the ride. The last few times I took a cab in NY, upon reaching my destination, I would casually open the door to leave, only to realize that I actually needed to pay and get my receipt before exiting the taxi. Uber has spoiled us, but when it has to do with efficiency and convenience, I am more than happy to be spoiled.

The Obvious Losers

Uber Drivers: The main losers

There is no question that in the short and mid-term (as long as we remain mostly around the existing equilibrium), the main losers are the current Uber drivers.

Within the gig economy, the economics are quite simple: the more supply you have, the lower the prices, and the higher the idle time for drivers.

In other words, the current Uber drivers will be making less money on Uber, and will have to wait longer for rides.

Lyft (and other gig mobility-only firms)

It’s not surprising that the market penalized Lyft after Uber’s announcement. The math is quite simple: Uber will have more drivers, and customers will pay less and wait less if they place requests on its platform. In a world where customers value speed and price, I do not see Lyft managing to compete in cities where Uber has incorporated taxis, unless Lyft also starts listing taxi drivers. And if I was the TLC: why not allow Lyft to do so?

Uber

But let’s take a closer look at Uber.

The obvious reaction is to assume that this is a big win for Uber, and in many ways it is.

As mentioned above, Uber will have access to a larger supply of cars and drivers, thus decreasing the need to offer additional incentives, which has been killing Uber financially for years. Since the early days, it was clear that the prices Uber was charging were not enough to pay the drivers, so it had to find outside motivators to keep drivers driving. This is not only true for Uber but for the entire gig economy. For example, by analyzing Lyft’s financial statement, one can gather that the incentives to drivers are around $1-$3 per ride. These incentives skyrocketed recently when the demand for rides increased, but drivers were reluctant to go back to work.

Another reason to be optimistic about the deal is Uber’s high desire to own the mobility space, the same way that Amazon wants to own the e-commerce retail space. In both cases, the firms are willing to list any entitiy that wants to be listed on their platform. In fact, I am pretty sure that Uber would be happy to list Lyft on its app if it could (albeit, it’s quite clear that Lyft wouldn’t be interested). That was the goal all along. but the assumption that all customers and drivers would leave their current options and move to Uber didn’t materialize. So striking this deal with taxis is a shortcut to get there. In a world where customers follow lower prices and faster supply, and supply follows the customers, this seems like an obvious win for Uber.

And finally, Uber is not only a mobility firm transporting people, it also has other services like UberEats, and grocery delivery. In Hong Kong, where Uber already partners with thousands of taxis, the company claims that 35% of users who hail a taxi through the app also end up using Uber’s other services. In its competition with DoorDash, having people spend more time and place more requests on the app can be a small benefit. However, I don't think this is going to be big in the US, and the reson is that for food, most people multi-home: they use both DoorDash and UberEats (and even Grubhub).

But…

The reason I am a little hesitant to claim that this is a complete win for Uber is the obvious loss for the Uber drivers.

As I mentioned above, the current Uber drivers are obviously losing from this agreement. But in a “free” economy, no one remains on the losing side for too long.

If prices for rides are going to go down, then gig workers that currently multi-home are going to go to platforms that have more demand for them,and platforms where the prices are potentially higher. As we argued before, this cannot be Lyft since Lyft will not be able to offer higher compensation in the long run without charging customers more, and customers will not pay more in a competitive market.

But most drivers have other choices (which is probably more true for cities other than New York), such as food delivery and grocery delivery. Why are these going to be less impacted by the agreement with taxis? Because taxi drivers do not deliver food.

In other words, the impact of this agreement will be, in my opinion, a win for DoorDash.

DoorDash has been in a battle with Uber in several markets (restaurants and groceries are two of them), and as the firm penetrates more markets (delivering for Macy's and CVS, for example), it can offer drivers a more diverse set of options. In many cities, it will be a more viable option instead of competing with taxi drivers.

In other words, I don’t think we can assume that the number of Uber drivers will remain fixed. It will equilibriate based on the number of taxis that actually use Uber. The rest might move to alternative platforms where they will have better options.

It’s important to mention that the impact of such an agreement is clearly going to be more pronounced in certain places and less in others. New York City has 40K taxis and 80K Uber drivers, so the addition of taxi drivers might overwhelm the gig economy of the city. San Francisco, on the other hand, has around 50K Uber drivers, but only 1800 taxi drivers.

Finally, maybe I am overthinking this, but this may be Uber's “own goal” (to use a soccer analogy). Uber is going to become less appealing to gig drivers, who will probably move to the competing “ecosystem” of DoorDash. In turn, Uber will be stuck with a group of drivers, similar in size, that can now collectively negotiate their terms. The last thing Uber wants, is to be held hostage by a group of drivers.

This will not happen in a day, but in the long term, the new equilibrium will be one in which Uber relies much less on the gig economy. Whether this is good or bad is yet to be seen. Taxi drivers were the original gig economy drivers before we even used the term gig platforms. The only difference was that in accordance with the old world of gatekeeping, they had to have a license to operate and had rules to follow. The fact that they join the epitome of gig platforms as workers is just the next evolution of the gig economy. Gig platforms will have to learn how to deal with potentially organized groups of workers, in this case, protected and represented by the Taxi and Limousine Commission, and maybe this will open the door to other groups to organize.