The Baby Formula Shortage: What’s the Root Cause?

One of the most interesting, developing supply chain stories of the last few weeks is the ongoing shortage of baby formula. The story has many interesting angles, from trade policy to anti-trust, and everyone seems to be blaming everyone else.

But the most interesting angle, at least in my opinion, is the quality management aspect. Over the last few days, several revelations have surfaced regarding the “shocking” conditions inside the Abbott plant that manufactures these products:

“FDA inspectors found shocking conditions inside the plant, including bacteria growing from multiple sites, standing water, roof leaks and inadequate hygiene, he said. Four infants who consumed powdered formula from the Abbott plant fell ill and were hospitalized with Cronobacter infections, two of whom died.”

And even worse:

“the plant cannot reopen until Abbott takes hundreds of steps to fulfill the requirements under a federal consent decree to come into compliance with U.S. food safety standards.”

In more detail, the director of the FDA describes:

“The Abbott Nutrition plant in Michigan that was shut down in February, sparking a widespread baby formula shortage crisis, had a leaking roof, water pooled on the floor and cracks in key production equipment that allowed bacteria to get in and persist… He detailed ‘egregiously unsanitary’ conditions in the Sturgis, Mich., plant…”

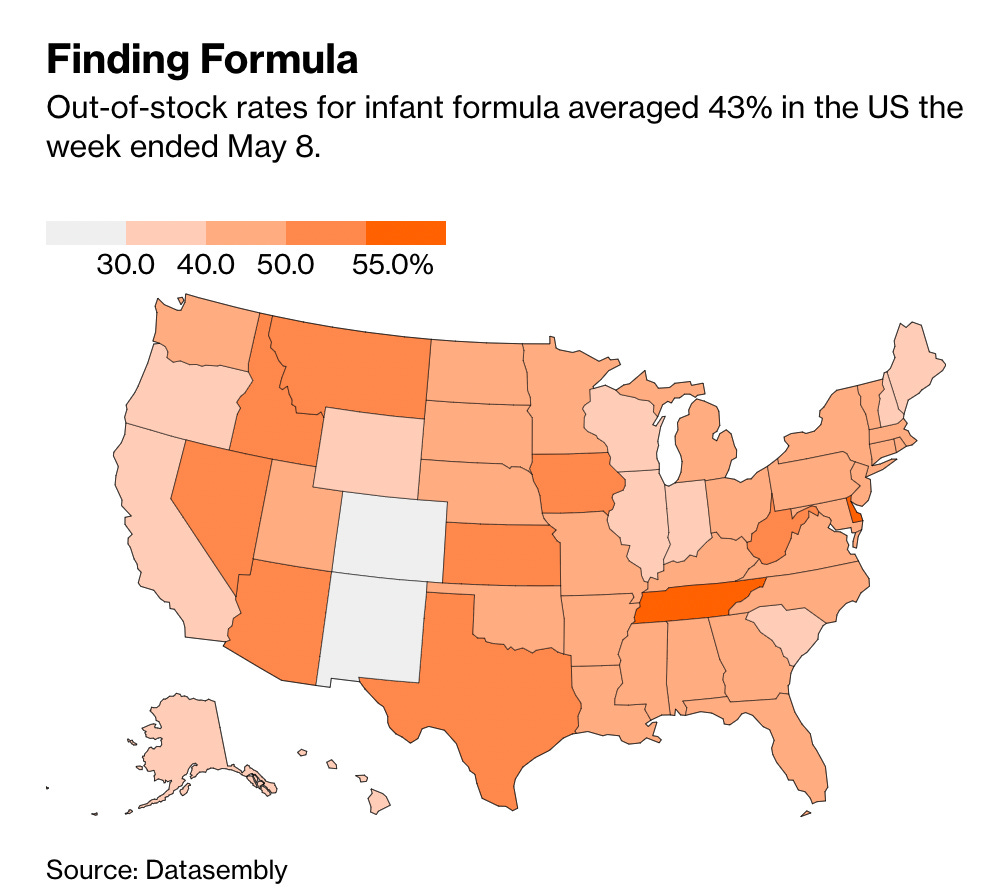

Just to give a bit more background: over the last few weeks, there has been a significant shortage in baby formula, with many states hovering around 50% stockout rates:.

These stockouts resulted in parents hoarding even more of these products, creating deeper shortages.

In trying to understand what triggered these shortages, it’s clear that everything started with Abbott closing its Michigan plant and recalling several infant formula products in February after FDA inspectors found Cronobacter bacteria at the facility.

But while this closure was the triggering event, it’s clear that this is not the root cause. A supply chain for such a product cannot and should not depend on one plant, unless the industry is highly concentrated. And indeed, four manufacturers, Abbott, Mead Johnson Nutrition, Nestle USA, and Perrigo, supply 90% of the domestic baby formula market in the U.S., and Abbott alone has a 40% share of the U.S. market. The Michigan plant, which was shut down, is responsible for 40% of the company’s U.S. production.

This raises many questions:

How is it possible that a plant that provides such a key product (and a highly regulated one) gets to such “shocking” conditions?

What does it say about Abbott in general?

How is this shortage related to the fact that this industry is highly regulated?

Let’s start with the first question. The government has acknowledged that it should have shut down the Michigan site long ago. In fact, it’s clear that the government was very slow to respond. Relevant information from “an anonymous whistleblower who said he worked in the Sturgis plant” was received in October 2021, and it’s clear that issues like pools of standing water and leakage in the roof don’t emerge over the course of a few weeks. These are persistent issues that should have been observed in previous visits.

In fact, based on the whistleblower’s report:

“Active efforts were undertaken and even celebrated during and after the 2019 FDA audit to keep the auditors from learning of certain events believed to be associated with the discovery of micros in infant formula at the Sturgis site.”

Now, before we continue to blame the FDA for its lax inspections, it is important to stop and name the main culprit: Abbott. And I don’t mean Abbott Nutrition, I mean Abbott Laboratories; the parent company.

Why?

One of two things are true: senior managers at Abbott either knew about the quality issues at the Michigan plant and did nothing, or they were completely unaware that these issues existed.

To be honest, I am not sure which one is worse.

If they knew and did nothing, it’s criminal negligence and they should be held accountable for it. I’m not a legal expert so I will leave it to others to comment on this, but I do hope they had no direct knowledge of this.

But if they were unaware, it doesn’t make it all that much better.

The fact that something like this was happening for so long (dating back to at least 2019) with such egregious violations needing hundreds of corrective actions, shows a very pervasive, cover-up culture, and a very relaxed attitude toward quality and safety.

People at the plant knew about the issues and did nothing.

People read the reports and didn’t alert anyone. In particular, the whistleblower refers to “The Falsification of Records,” and “Releasing Untested Infant Formula”:

“Complainant raised his concerns as to what was taking place with other members of QA leadership. Complainant was told that the Sturgis site was required to notify officials at the division level that a nonconforming product had been released. It is Complainant’s understanding that there is a ‘grading’ scale based on severity that Abbott uses in these situations. However, despite the objections of staff, he was told by those directly involved that the Sturgis site intentionally misrepresented the severity of the issue to division officials.”

Let me be clear. This cannot be an issue only in one plant. It just can’t. It’s also not an issue unique to Abbott Nutrition. When we see issues of this type, it is usully the tip of the iceberg. For such egregious issues to happen, both on the quality and the reporting level, a deep culture that supports this behavior must be cultivated for years.

So this is a leadership issue, and one that stems from the highest levels of leadership.

I will make the strongest statement I have made in this newsletter: Any day that Abbott’s CEO still has a job, is a day that Abbott’s shareholders are ok with a culture of cover-ups, and therefore shouldn't be surprised with the next recall.

Again: this is not only about government regulation. Firms should be the ones regulating themselves.

When I teach lean operations, I discuss “quality at the source.” The idea is that even if high quality is not your main competitive strategy, you want to pay attention to quality issues at every possible level, and in every possible stage of the value chain because correcting them at a later stage, will have significant costs and reputational implications. Again: this is to be considered from Abbott’s shareholders’ POV, not the government.

It may sound naive, but my opinion is that Abbott should ask themselves how such a situation arose in the first place. In fact, they should shut down all their plants and conduct a whole root cause analysis of how such a culture was allowed to prevail.

And Abbott is not the only firm that has a culture of cover-ups. There have been similar issues at Boeing.

You may be wondering what the similarities are between these two industries: baby formula and aerospace. There are a few, but the most evident and important one is that due to heavy regulation, both industries are highly concentrated.

Quality, like resilience, is something that costs money in the short run but pays off in the long run. Unless there is a deep competitive pressure or risk of shutting down (or going bankrupt), firms will prioritize the short run. And this is exactly what happened at Boeing, where engineers raised concerns about quality issues, but because Boeing was a local monopolist, management chose to overlook the warnings.

It's much cheaper to build a low-cost supply chain, reduce the number of quality inspections and corrections, and pray that nothing happens. There is always a tradeoff. The same is now happening with the baby formula crisis. Firms have to balance the cost of maintaining high quality and safety standards with the risk of a recall or significant quality issues being revealed (either through inspection, or death, or damages caused by the product).

Robert Bray has an interesting paper on this topic in the automotive industry. Using simulation, he shows that automakers initiated recalls to reduce the future defect rates but not to avoid expected government recalls. Interestingly, his study shows that the savings from future defect costs is what triggered the majority of manufacturer recalls.

But can this be extended to food and drugs? I decided to check how many recalls Abbott has had over the last few years, working under the assumption that, given how shocking the conditions were at the plant, this can’t be a one-time event.

The FDA website provides safety alerts for both firm-initiated and government-mandated recalls. The list shows that since 2017, Abbott has only had 5 recalls across all its products, 2 of which were related to this year’s Similac recall in February and March; the two that triggered the current shortage. During the same period, Pfizer has had 10 recalls across their entire product range, so I was very surprised at Abbotts’ numbers. How is it possible that there are so few recalls when there are such serious violations being noted?

The way I see it, there is just not enough competitive pressure to punish firms that allow defective and life-threatening products to be released in the market. Definitely not in the baby formula market.

Why?

My answer is that this is, in fact, driven by the very strict regulations:

“Since 1989, federal law narrowed competition by requiring each U.S. state to choose a single company to supply formulas available to low-income families under the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, known as WIC… There are companies — other manufacturers that have had to wait years to come to market because of FDA delays,”

So, tough regulation on new entrants and decisions that create market concentration, together with relaxed regulation once the products are in circulation, resulted in less pressure on firms to be their own careful quality and safety controllers. This type of “foul play” is ultimately what led to the shortage we are now seeing.

All this is very much related to the idea of Legibility. The actions taken by the government, which were meant to simplify the management/handling of these products, in fact resulted in the creation of very brittle supply chains, ultimately causing more damage than good.