Cocoa prices are increasing, which some people say is the worst crisis in the global chocolate industry.

As usual, when it comes to supply chains, there are root causes for such a crisis, and there are solutions that aim to alleviate or mitigate these issues that, in the wrong circumstances, make matters worse.

So, let’s go deeper into the muddy world of cocoa.

The Root Cause

The immediate cause of the price hike is the mismatch of supply and demand. There is more demand for cocoa than there is supply.

But this is all too obvious. The question is, what’s causing this mismatch?

While demand is increasing, it is nothing out of the ordinary.

The issue is supply.

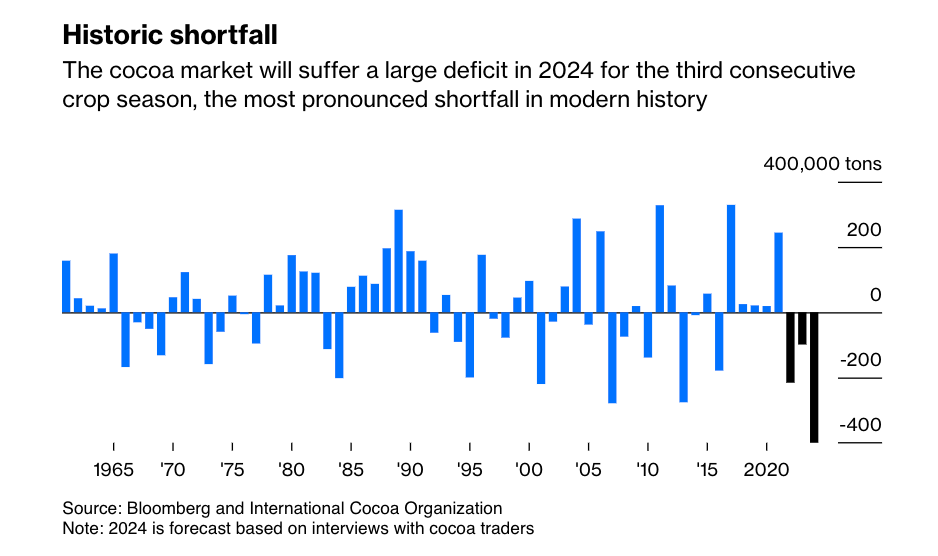

Indeed, during the last three years, we saw a historic shortfall:

What’s causing this shortfall?

“Adverse weather conditions, smuggling and disease have contributed to higher prices, resulting in lower yields in Ivory Coast, which produces nearly 40 percent of the world’s cocoa beans, and Ghana, which produces 20 percent. El Nino, a weather pattern that causes drought in West Africa, has had a significant impact on cocoa production in the countries mentioned. Strong seasonal winds and lack of rainfall also contributed to the shortage, forcing traders to scramble to stock up and raise prices.”

But the weather conditions aren’t the root cause either.

“‘The problem with cocoa is that’s a poor man’s crop,’ explained my dining companion, a government official-turned-businessman. ‘Do you see any commercial plantation around here? No,’ he said. ‘And do you know why? Because prices aren’t high enough.’ Unlike most other agricultural commodities, cocoa hasn’t developed into a plantation business. At the prevailing prices of the 1990s and 2000s, it simply didn’t make commercial sense. The money was made around trading the beans, and processing them into chocolate — not planting, growing and harvesting cocoa trees.”

You can see the prices below:

As prices were so low for a significant period of time, there was a need to be cost-efficient. What does a rational farmer do? Invest in more cost-efficient farming methods. As we previously discussed in this newsletter, a cost-efficient operation usually means a more “fragile” operation—one that is much less capable of dealing with demand and supply shocks.

The Bitter Consequences of Monocropping

In the quest for efficiency and maximized yields, the global agricultural landscape has increasingly leaned toward monocropping—the practice of growing a single crop over extensive areas, season after season.

This is what monocropping (or monoculture) looks like:

While this approach may offer short-term economic benefits, it harbors long-term risks, particularly regarding supply chain resilience. With its heavy reliance on cocoa, the chocolate industry illustrates how monocropping can erode the stability and sustainability of global supply chains.

Monocropping aims for optimal soil use and adapts to the prevailing climate conditions. Typically, farmers choose crops most likely to prosper in their specific environmental setting. This method’s benefits are particularly evident in cultivating rice, which thrives in wetland-like conditions, and wheat, which grows best in flat, sun-drenched areas. Crops selected for their ability to withstand or flourish under certain climatic challenges, such as drought, wind, or cooler temperatures, are central to a monoculture agricultural approach.

In contrast, traditional farming practices focus on cultivating various crops, following a detailed schedule for planting, maintenance, and harvesting to enhance the yield of diverse crops. Despite the greater effort required, the efficiency and productivity of monoculture farming often surpass those of more varied agricultural methods. Essentially, this means that monocropping simplifies farming operations and can lead to economies of scale in crop production.

However, this method has downsides, often leading to biodiversity loss, soil degradation, increased vulnerability to pests and diseases, and dependency on chemical inputs like fertilizers and pesticides to maintain yields. Over time, these factors contribute to the diminishing health of the ecosystem, making it less capable of supporting crops. This is particularly alarming for crops like cocoa grown in some of the world’s most biodiverse regions.

Cocoa is predominantly grown in West Africa, which accounts for over 70% of the world’s cocoa production. Monocropping has become prevalent in these regions as farmers strive to meet the growing global demand for chocolate, which, unfortunately, makes the cocoa supply chain highly vulnerable. A single disease outbreak, such as the Cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus (CSSV), or a significant pest infestation can decimate entire harvests, leading to significant supply disruptions and price volatility.

Soil erosion, loss of soil fertility, and decreased water quality are just some of the negative outcomes that pose a significant threat to the long-term viability of cocoa farming. This environmental degradation further exacerbates the supply chain’s vulnerability, making recovery from disruptions more challenging and lengthy, which is exactly what we are seeing now.

What can be done?

To mitigate these supply-side risks, there is a need for concerted efforts toward sustainable farming practices. Initiatives that encourage biodiversity, such as agroforestry, where cocoa trees are grown alongside other types of plants (as seen below), can help reduce the risk of disease and pest outbreaks while improving soil health. However, shifting back to such practices requires a collective effort from the entire supply chain, including chocolate manufacturers, governments, and NGOs, who can provide the necessary incentives, support, and education to cocoa farmers.

Once growers have shifted to mono-crop systems, transitioning back to more diverse agricultural practices, such as agroforestry, becomes challenging. The initial investment in a mono-crop system and the subsequent land degradation and loss of biodiversity make it difficult and costly to reintroduce variety into the ecosystem. Furthermore, the knowledge and infrastructure necessary for diversified farming may require recovery or improvement, adding another layer of complexity to the transition.

In other words, there’s no short or medium-term solution.

The reliance on monocropping in the chocolate industry offers one more illustration of the risks of prioritizing short-term productivity gains over long-term sustainability and resilience (“Did someone say, Boeing?”).

As global demand for chocolate continues to increase, there’s an urgent need to rethink agricultural practices to ensure that the sweet indulgence remains available for future generations. By embracing biodiversity and sustainability, the chocolate supply chain can become more resilient, securing the livelihoods of farmers and the pleasure of chocolate lovers worldwide.

Financial and Operational Hedging

But as usual, supply chains are more complex than they seem, and countermeasures can make matters worse.

The recent Bloomberg article outlines how financial hedging is making the situation worse.

To understand what it means, imagine cocoa traders who own a stockpile of cocoa beans or cocoa-based products such as liquor, butter, and powder. To guard against financial losses if prices fall, these traders often make counter bets in the financial market. This strategy, known as hedging, is supposed to balance out: if the market price of cocoa rises, any losses from these financial bets are offset by the increased value of their physical cocoa holdings.

However, there’s a catch. These financial contracts, or bets, take time to settle — sometimes several months. During this period, if the market moves against them, traders need to come up with extra cash to cover potential losses, known as making margin calls. Under normal circumstances, traders would use their cash reserves or borrow money to cover these calls.

But when cocoa prices soar unexpectedly, as they’re doing now, the required cash to meet these margin calls can quickly exceed what a company can comfortably afford. This can put even financially healthy companies in a tight spot, forcing them to unwind their hedges (drop their protective bets) to free up cash. It’s a balancing act, and in a surging market, maintaining this balance can become overwhelmingly challenging.

In this newsletter, I discussed quite a bit about how firms use operations to hedge against commercial or operational risks. But sometimes, firms use financial instruments to hedge against operational and commercial risks. This is part of what we call the finance operations interface.

The paper “Managing Storable Commodity Risks: The Role of Inventory and Financial Hedge” by Panos Kouvelis, Rong Li, and Qing Ding explores how firms can manage risks associated with the prices and consumption volumes of storable commodities through both physical inventory management and financial hedging. The study focuses on a risk-averse firm that procures a storable commodity at a random price from the spot market and a fixed price from a long-term supplier. The firm also engages in financial markets through instruments like futures contracts, call options, and put options to hedge against commodity price volatility.

The analysis shows that hedging may lead to a reduction in inventory levels in multi-period problems.

The Bloomberg article mentions traders employing short positions in futures to hedge against their physical inventory, reflecting the financial hedging aspect of the Kouvelis model. The model in the paper suggests that financial instruments, like futures and options, can be used to hedge against price volatility, which the traders initially attempted to do.

As cocoa prices began to rise, the market dynamics shifted from being fundamentally driven to being influenced by financial factors and speculative behaviors. Kouvelis et al.’s work highlights how firms can employ financial instruments like futures contracts and options to hedge against such price volatility. However, in an unruly market phase, the effectiveness of these hedging strategies might be compromised, as highlighted by the challenges cocoa traders face with margin calls and over-hedged positions.

The Bloomberg article describes how cocoa traders, facing a bull market, struggle with financial hedging strategies that become less effective as prices soar. Traders who took short positions in cocoa futures as a hedge against their physical inventory find themselves in a bind as they need to meet margin calls due to the increasing value of their physical holdings. This scenario aligns with the discussion in Kouvelis et al.’s paper about the complexities of integrating inventory management with financial hedging, particularly in volatile markets where price movements are rapid and significant.

In conclusion, the surge in cocoa prices from a fundamentals-based increase to a speculative frenzy demonstrates the critical need for robust risk management strategies, as discussed in the paper by Kouvelis et al. However, the article also illustrates the limits of these strategies in extremely volatile markets, underscoring the need for additional safeguards and regulatory oversight to protect market stability and participants.

Bottom Line

The challenges the chocolate industry’s supply chain faces due to monocropping and moving toward more industrial farming practices highlight a critical aspect of almost any sector we examine these days: the tension between short-term economic gains and long-term sustainability.

Addressing these challenges requires reevaluating agricultural practices, market mechanisms, and the role of various stakeholders in supporting a transition toward more resilient and sustainable farming methods.

It’s clear that we need a collective approach to mitigate these challenges, involving stakeholders across the supply chain. The transition back to sustainable farming practices requires not just the willingness of the cocoa farmers but also the support of chocolate manufacturers, consumers, governments, and NGOs. These entities must work together to provide the necessary incentives, resources, and education to support sustainable cultivation.

This is one more example of how good intentions when dealing with risks can actually spiral out of control.

Finally, I must confess that I’m not a huge chocolate fan, so this article is written in pity (and a little sympathy) for your chocolate lovers who must now consider taking out a mortgage to finance your next chocolate bar binge.

Excellente article! Congrats, professor Allon!