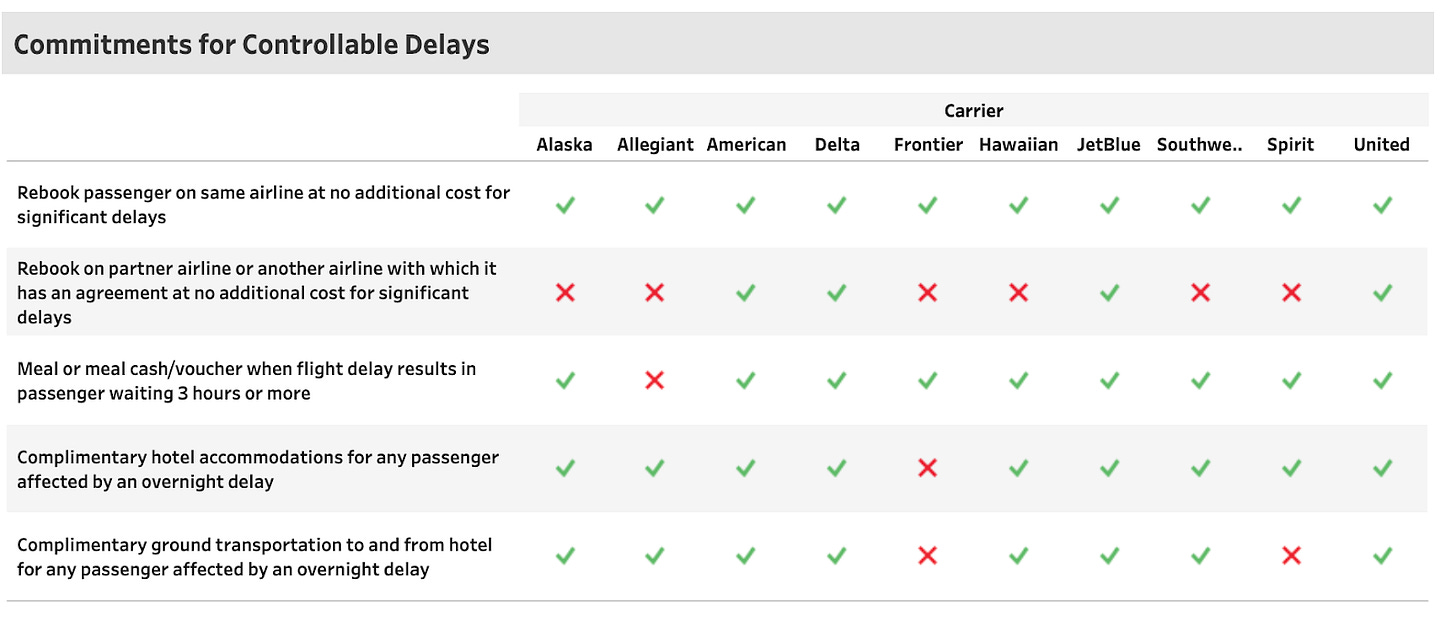

A week ago, the Department of Transportation unveiled a very exciting, new initiative: the Airline Customer Service Dashboard.

Here is a snapshot of what you see if you visit their website (at the time I was writing this post):

And,

The explanation is clear:

“The U.S. Department of Transportation has created a dashboard to ensure the traveling public has easy access to information about services that U.S. airlines provide to mitigate passenger inconveniences when the cause of a cancellation or delay was due to circumstances within the airline’s control. A green check mark on the dashboard means an airline has committed to providing that service or amenity to its customers. A red “x” means the airline has not made that commitment. However, airlines with a red “x” may provide these services and amenities in some instances in their discretion.”

The Upside

First, this is a great development. I love transparency, and a lot of my research has been on providing consumers with information on operations. Transparency is helpful in informing consumers what they deserve, and customer service representatives what their employer has promised. Airlines are complex, and I have had several instances where I had to let the agents know what I “deserve” (one story includes a 14-hour delay, two very young kids, and a dog, so I will spare you the details).

In a competitive world, a dashboard like this makes it easy for consumers to decide which airline to patronize. It’s not surprising that the three major carriers, United, Delta, and American Airlines all have green check marks in every line.

Furthermore, the airlines themselves admitted that they added services they didn’t offer before because of this initiative:

“United ‘rewrote its customer commitments to be clearer and readable to travelers,’ a spokesperson told Insider. The airline will now offer meal vouchers to passengers whose flights are delayed more than three hours instead of four hours, the airline’s website shows.”

The same article mentions that “American Airlines has also updated the language in its customer service plan to ‘clarify’ the company's existing policies,” while someone from Delta mentioned that “[we] updated some of our language to be explicitly clear about the services and amenities we provide customers when they are inconvenienced.”

So this is clearly a situation where market dynamics improve, by removing information asymmetry.

But I am quite sure that there are several “rights” or “compensations” that should be there but are not, since airlines lobbied to not have them there.

What’s not There?

This brings me to the question of whether this dashboard is as good as it looks.

And the answer is no.

If you read the title of each table, you can’t miss the terms “Controllable Delays” and “Controllable Cancellations.”

“A controllable flight cancellation or delay is essentially a delay or cancellation caused by the airline. Examples include: maintenance or crew problems; cabin cleaning; baggage loading; and fueling.”

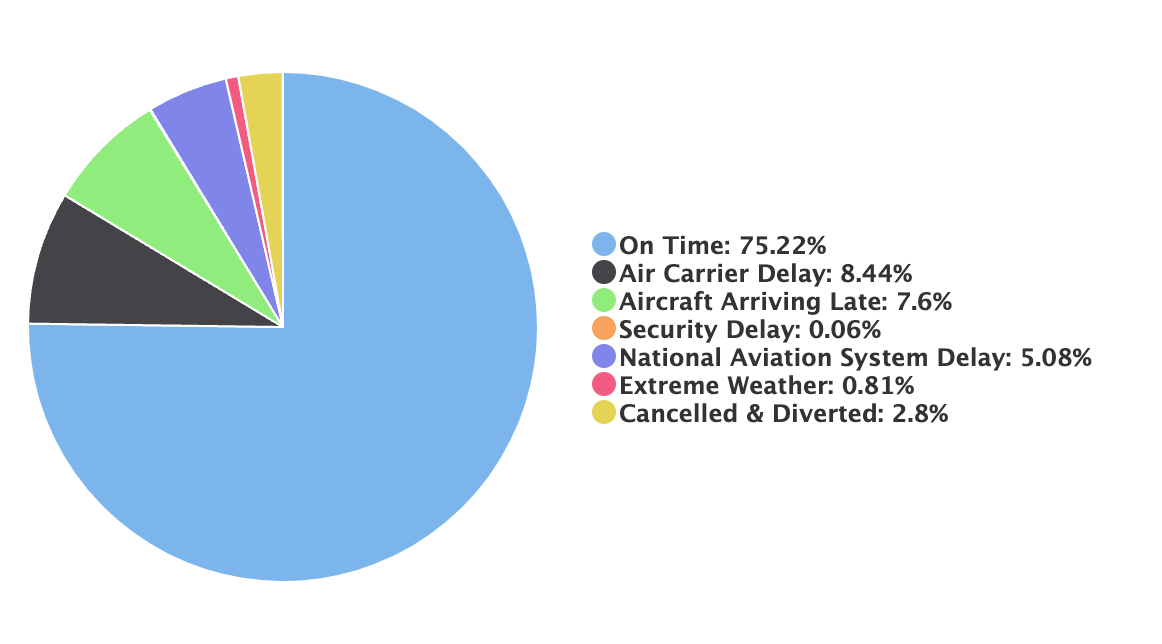

If we look at the main reasons for delays based on the DOT data from past June (which had above-average delays), we discover some interesting information.

Around 75% of the flights were on time.

But let’s focus only on delayed flights: About ⅓ were air carrier delays (which can be related to maintenance, crew, etc.), ⅓ were causes unrelated to the airline (national aviation, security, weather), and ⅓ were related to the aircraft arriving late. The latter is probably further divided similarly to the previous two cases since planes arrive from airports that are experiencing similar issues. In other words, I would approximate that ½ of the time, delays or cancellations will be airline controllable and the other ½ uncontrollable.

If we look at flight cancellations (which are much rarer):

About ⅓ are issues related to the carrier, and the rest are related to other factors.

So the dashboard really focuses only on the rights for “controllable” delays and cancellations, which are between a half and a third of the instances.

There are three questions here:

(I) Why shouldn’t airlines compensate you for uncontrollable delays (beyond the need to refund all canceled flights, which is mentioned in the dashboard)?

(II) Even if airlines are not obligated to compensate you, shouldn’t they compensate you?

(III) Even if airlines don’t have to compensate, and most decide not to, shouldn’t the dashboard include aspects that are related to these not-yet compensated situations, thus creating incentives for airlines to do so?

To try to understand my insistence on this, we need to understand the following:

the actions firms take, which are meant to mitigate the impact of these (controllable and uncontrollable) delays and cancellations, and

the costs of these actions.

Controllable delays can be addressed by better staff training, having more crew on board, or ensuring that the cleaning team is ready. Some solutions (like having more crew members) are costlier than others, but they all help make sure planes leave on time.

Airlines can also mitigate the impact of delays, both controllable and uncontrollable. We already discussed the use of padding as a solution, where airlines create a buffer between flights, so that one flight’s delay, doesn’t impact other flights that depend on it.

But padding is exactly what can help an airline reduce the impact of not only controllable delays, but also uncontrollable delays, such as weather issues, or long security lines. While these are clearly not caused by the airline, it’s clear that some airlines handle them better than others.

Let’s look at three airlines.

United, Southwest, and Delta (respectively):

Delta is on time more often and blames “aircraft arriving late” less often than the other two airlines. At the same time, we can also see that it canceled more flights.

I know that their hubs are impacted in different ways, given the different locations, but still, airlines make decisions and have cost implications (which I will discuss in a second) as well as customer service implications (in terms of delays and cancellations). We want airlines to make better decisions and provide a better service.

Costly Differentiation

Given that padding (or any other delay-mitigating measure) has a cost, the question is whether airlines should be forced to compensate passengers even when the delays are not the airlines’ fault.

This is a tough question, and is essentially, question (I) from above.

I think this is something the market should solve, and exactly what the role of this dashboard should be.

Since we created a dashboard for issues related to delays, let’s also create an incentive for airlines to differentiate themselves in terms of how they handle delays.

Imagine an airline like Delta saying: “We will compensate passengers regardless of the reason of the delay (even weather-related ones) since (a) we have fewer delays, and (b) we choose to maintain our high level of service no matter what. This will make it very hard for other airlines to copy Delta without incurring higher costs than Delta. But that is exactly the differentiation I would want to see.

So the answers to questions (II) and (III) above are yes. Airlines should try to differentiate themselves by how they handle delays (controllable and uncontrollable), and the dashboard should motivate them to do so.

Again, this is not only about the ability to compensate. It’s really a costly signal for quality. It’s easy to say or copy the phrase “passengers come first,” but incurring an actual cost for this is another story.

The Cost of Mitigating Delays

We already discussed Delta’s decision to compensate flight attendants for on-time performance, so Delta is more on-time for a reason.

We also discussed padding as an option, so let’s look at the costs (and with them, the impact the dashboard has on these costs). In setting up a schedule and padding strategies, airlines need to balance their cost of being or not being on time, their customers' aversion to delays, and their customers’ aversion to excessively long flights.

If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it’s probably a newsvendor problem.

And indeed, Van Mieghem, Salant, and Zhang study the problem of increased flight duration, and model it as a newsvendor problem.

The left-hand side is the optimal probability that the flight is on time. The right-hand side is the critical fractile (that we all love in the newsvendor problem): accounting for the customers’ aversion to delays (ln), the firm’s aversion to delays (lon/p), the customer disutility from the length of the flight (cn), and the airline’s disutility from having longer flights (con/p).

We all want to be on time, have short delays, and the shortest flights possible, but in an uncertain world, this is impossible. The equation demonstrates the need to balance underage and overage. Having a short posted time and no padding (but possible disruptions), or posting long flight times (but alienating passengers that want shorter flights) and losing money from low plane utilization.

How much do you need to pad?

If the cost of a longer flight is higher (e.g., the cost of additional crew members, which I know is not exactly accurate, but a good approximation), then the airline will target a lower service level, but it will also require less padding:

The more efficient an airline is (lower costs), or the lower variance it has in flight time, the less buffer the airline needs to add.

Note that the higher the cost the airlines incur for being late (both in terms of customer aversion and operational costs), the higher the on-time performance they should target.

Back to the Dashboard

You can already see the impact this dashboard has had since we started the discussion with: it should increase the operational cost of being late. Imagine 100 customers demanding hotel accommodation or meals they didn’t know they deserved. I am quite sure that until now, airlines either didn’t compensate (as they admit above) or just played on the fact that customers weren’t aware.

So this sets my prediction for the next few months:

Will we see an increase in the level of on-time performance now that airlines will be dealing with increased customer awareness; customers who will demand the meals and hotel accommodations they deserve for each delay?

Yes: I expect airlines’ on-time performance to improve.

And yes, I hope more airlines offer compensation even for uncontrollable delays, once they figure out that this can be an area of differentiation.

But maybe airlines are already differentiating to some extent. While not all passengers get a free meal when a flight is delayed, those who fly business or have lounge access can enjoy the services that lounges offer, such as meals, showers, quiet/rest areas, etc. So maybe airlines have already incorporated “compensation” for the passengers they care about (who also spend enough money to be cared for). As for the passengers the airlines don’t care much about, I think the feeling is mutual, so I don’t see much changing.

The equilibrium will remain similar to the one we have now, but maybe the components will shift. We won’t see differentiation between airlines, but differentiation within the airlines’ passengers, but hopefully, fewer delays for all!

Prof. Allon, a great read. 1 of your more equation backed reasoning :).

Metrics and dashboards are great drivers to focus on behavior and hence drive improvements / efficiencies. However, follow through with the right processes are key to sustainability.

In this case the airlines could drive away passengers, intentional or not, with cumbersome processes (long queues to get vouchers, forms, etc.). The added operational costs and processes need to be seen all the way through till serving the passenger for this added benefit. Else the airline may look good on the dashboard but leave behind a frustrated customer.

Suraj

(Long time reader, first time commenter!)