This Week’s Focus: Is “Unbossing” the New Norm?

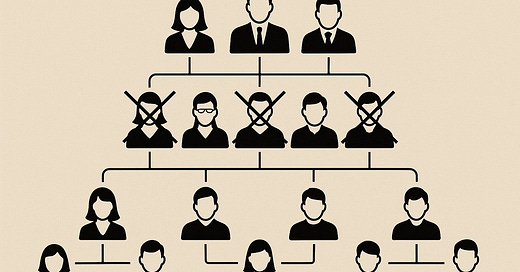

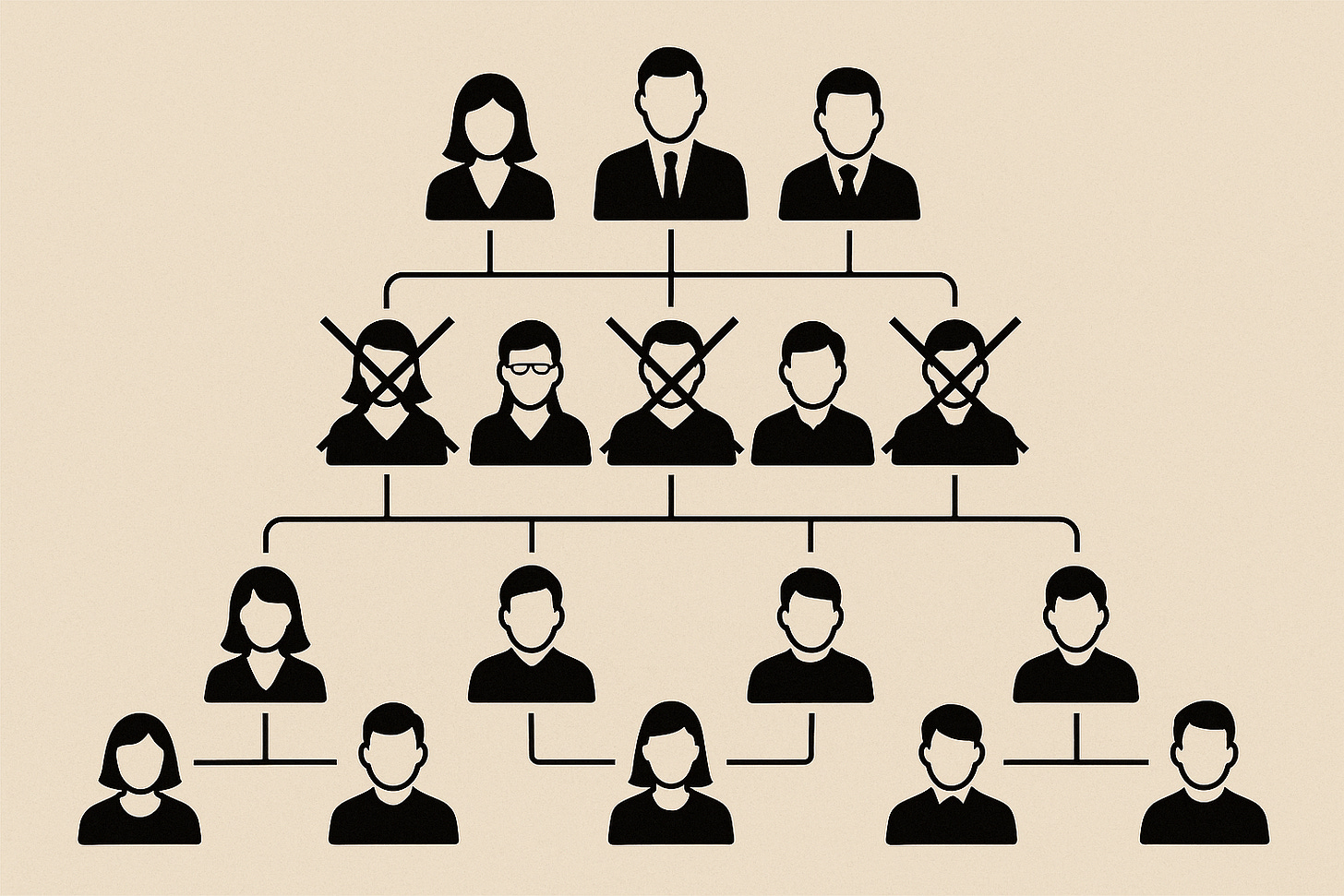

From Trump tariffs to post-pandemic slowdowns, companies are aggressively pursuing efficiency due to current financial strain. One growing trend: cutting out management layers, also known as “unbossing.” The term refers to removing bosses, particularly middle managers, to trim expenses and streamline operations. While U.S. firms have delayered before in the 1980s, the practice resurged amid the tech layoffs of 2022–2023, with companies initially aiming to reduce their overall headcount, and seems like it’s still going strong in 2025. Is unbossing a lasting shift in organizational strategy—or just another reorg in disguise? Today, we explore this trend drawing from academic research and company case studies.

It seems that in 2025 the corporate world is becoming flatter.

According to Axios, recent economic pressures—from tariff-driven cost increases to post-pandemic slowdowns—have companies seeking efficiency wherever they can find it. One tempting target that has emerged is cutting management layers: managers generally earn higher salaries than front-line employees, so eliminating manager roles can quickly trim substantial costs.

The trending term is “unbossing” —essentially removing bosses, and especially middle managers. This concept isn’t entirely new—U.S. firms delayered in the 1980s under competitive pressures, but it’s back with a vengeance in the 2020s.

A new Korn Ferry report highlighted just how widespread this “great flattening” has become. In late 2024, a survey of 15,000 workers across 10 countries, 44% of U.S. respondents said their company had “sliced away managerial levels” in the past year. In other words, nearly half of workplaces—spanning tech startups, Fortune 500 firms, and beyond—have actively removed one or more rungs of the org chart.

The current wave of unbossing took off amid the big tech layoffs of 2022–2023, when companies like Meta, Google, and Amazon shed tens of thousands of jobs. Initially these cuts were about reducing overall headcount, but they increasingly focused on managers, who were seen as an expendable layer “in between” the people doing the core work.

Interestingly, the Axios report on unbossing linked the trend not only to tech layoffs, but also to geopolitics and rising costs, noting that manager cuts accelerated “in the wake of Trump tariffs.” In other words, higher expenses (like import tariffs or inflation) squeezed margins and forced companies to find savings internally.

Middle managers, being a cost center that doesn’t directly produce revenue, is an obvious line item to reduce. By unbossing, firms hope to preserve more of their core workforce (engineers, salespeople, analysts, etc.) while still cutting total spending.

It’s also worth noting the timing, since just a couple of years ago, headlines were dominated by the “Great Resignation,” with workers quitting in droves and a hot job market. Companies were scrambling to hire and perhaps over-hired managers to oversee growth. Fast forward to 2023–2025: the narrative flipped to what some call the “Big Flattening.” As economic outlooks darkened, layoffs hit, and now those extra layers added during boom times are being peeled back.

In any case, whether driven by crisis or opportunity, unbossing seems to have become a go-to move for many CEOs aiming to boost efficiency.

Is this another copycat culture trend, just another term for reorg, or is it a real move that is here to stay?

Let’s cut through the hierarchy.

Case Study: Meta’s “Year of Efficiency” and the Manager Exodus

In late 2022 and early 2023, Meta undertook a dramatic restructuring. Thousands of employees, many of them managers or team leaders, were laid off. Those who remained saw org charts reorganized and flattened. Meta’s internal rallying cry became “do more with less management.”

Zuckerberg’s Rationale: Mark Zuckerberg argued that bloated hierarchies were slowing Meta down. Decisions had to go through too many approval layers. By cutting out middle managers, information could flow more directly from upper leadership to the teams actually building products, and vice versa. He wanted engineers and designers to be closer to the company’s top strategic direction without multiple managers in between. The famous quote—originally from an internal all-hands—“Managers managing managers managing managers…,” was his way of critiquing hierarchies. In Zuckerberg’s view, each layer of management is like a filter or speed bump: remove enough of them and communication should speed up, alignment should improve, and teams should feel more empowered to act fast.

What Meta Did: In practice, Meta offered managers a choice: take on larger teams of direct reports (in some cases doubling their span of control), or transition to an individual contributor role (essentially “demote” to a non-managerial position focusing on hands-on work). Managers who neither had large enough teams to justify their role nor the desire to return to the trenches were inevitably let go. The company also scrapped some manager positions entirely—for example, if a team had a manager and a sub-manager (like a tech lead under a director), they would remove the sub-manager role so that the team reports directly to the director.

Outcomes at Meta: The immediate outcome was a leaner org chart. Meetings and approvals were reduced. According to Meta, this contributed to faster decision cycles on projects. It also clearly pleased investors: as noted, Meta’s stock soared upon news of the aggressive cost-cutting and focus on efficiency. Financially, cutting thousands of employees (many of them managers earning six-figure salaries) saved billions in operating costs (Meta took a one-time $4.2B restructuring charge), implying future savings of that magnitude.

However, the cultural and operational impacts were mixed—a microcosm of the broader unbossing debate. Some Meta employees publicly (and many privately) applauded the new agility. Engineers felt the bureaucracy had eased; fewer interminable meetings with layers of managers, more direct communication with higher-ups.

On the other hand, some employees described increased ambiguity: with their old managers gone, they weren’t always sure who to go to for decisions or mentorship. Many felt a gap in middle leadership leaving some teams feeling a bit directionless.

Beyond Meta: A Wave of Flattening Across Tech

Many other companies also flattened their hierarchies in 2022–2023. Google cut 12,000 positions and encouraged managers either to expand their teams or return to individual contributor roles, aiming to reduce layers and eliminate silos. Similarly, Amazon eliminated about 27,000 roles, targeting mid-level management positions, streamlining operations, and revisiting Jeff Bezos’s principle of smaller teams (“two-pizza teams”). Former Twitter, now X under Elon Musk, took the most drastic approach by slashing roughly 80% of its staff, essentially removing entire management chains and having engineers report directly to Musk, creating a notably flattened structure.

Startups, facing reduced venture funding, also adopted leaner structures, with founders directly managing teams or empowering self-managed groups. Outside tech, large firms such as banks and pharmaceutical companies announced similar restructuring efforts to eliminate bureaucracy. Ford aimed to become more agile and software-oriented by flattening its management hierarchy as it shifted to electric vehicles.

Early experiments like Zappos’ adoption of holacracy, where managerial titles were completely eliminated, showcased earlier forms of this ethos. By 2025, flattening had become widespread enough that CEOs routinely emphasized unbossing initiatives, though the long-term costs and impacts of such extreme structural changes remained uncertain.

Conway’s Law: Does Structure Mirror Communication (and Product)?

One way to analyze unbossing is through the lens of Conway’s Law. Melvin Conway, back in 1968, observed that “organizations which design systems ... are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.” In plain terms, the way teams are structured and communicate will influence the products or systems they create. A classic example: if a company has four different teams working separately on a software project, they might end up building four separate modules that bolt together, because that’s how communication flowed.

Now, what does Conway’s Law imply for a company that’s suddenly flatter? Flattening an organization changes communication paths. With fewer layers, the distance from a junior engineer or analyst to the CEO (or to a decision-maker) is shorter. Theoretically, information can flow with less distortion—like a game of telephone with fewer intermediaries. We might expect a flatter company to produce simpler, more integrated products because the communication structure is more direct and integrative.

On the other hand, hierarchy isn’t always bad for communication. Hierarchies create defined channels: e.g., a team reports to a manager who aggregates and filters information up to higher management. In a flat setup, those formal channels are replaced by more ad-hoc communication. That can be faster, but also potentially messier. There’s a risk that in a very flat org, everyone is talking to everyone (or trying to), resulting in noise or confusion about who is deciding what. Conway’s Law would suggest that such an organization might create products or outcomes that are similarly disorganized or conflicting.

Consider the following product development scenario: In a traditional hierarchy, a Product Manager might coordinate between engineering, design, and marketing—acting as a communication hub. In a flat structure, those three functions might interact directly in a more peer-to-peer network. This can yield great results if they coordinate well—faster cycles, no waiting for “manager approval.” But it can also lead to misalignment if each function interprets goals differently. The organizational design has to be intentional so that communication patterns still align with the company’s goals even when formal hierarchy is minimal.

A classic example illustrating how a flat organizational structure can produce problematic or disorganized products due to messy communication is Valve, the well-known gaming company famous for its radically flat, managerless model. While Valve's flat structure fostered great innovation in some cases, it also led to notable product delays, inconsistent updates, and fragmented game releases (famously, the long-promised and much-delayed Half-Life 3, which has become an industry punchline). The lack of clearly defined communication and decision-making channels at Valve created ambiguity about project priorities and authority, ultimately causing confusion, duplicated effort, and unfinished products.

Some companies leverage Conway’s Law in reverse: Design the organization you want to be mirrored in your products.

For instance, Amazon’s two-pizza team concept essentially creates mini start-up-like units, responsible end-to-end for a service. Communication within each small team is tight, and their service can be built and iterated quickly; the product architecture (lots of independent microservices) mirrors that team structure. Imagine an organization that’s completely flat but still huge—thousands of individuals all theoretically on equal footing. In practice, it wouldn’t function as a single, giant, self-organizing team, but rather as several informal groups or networks that tackle different issues, potentially competing or duplicating work. Without proper guidance, this could lead to a fragmented product—often referred to as “design by committee.”

In practice, successful unbossing often involves redefining how communication happens outside of the old hierarchy. Many companies invest in better collaboration tools, clearer documentation of decisions, and cultural norms that replace the role of a manager as an information conduit. If done well, a flat organization can indeed be more nimble, with communication patterns that favor rapid iteration, and products that benefit from that agility. If done poorly, Conway’s Law warns that a broken communication structure (e.g., chaos or constant confusion) will result in a broken output.

What Do Middle Managers Actually Do?

Before we celebrate the extinction of middle managers, let’s consider what we lose when we remove them.

Alignment and Direction: Managers align team efforts with company strategy, preventing teams from becoming directionless and inefficient.

Coaching and Development: They mentor, provide feedback, and support career growth—functions hard to replicate in flatter structures.

Bridging Top and Bottom: Middle managers serve as connectors, translating high-level strategy into actionable tasks and escalating issues upward, preventing senior leadership from being overwhelmed.

Institutional Memory: They retain crucial knowledge about organizational practices and past mistakes, helping teams avoid repeated errors.

Handling People Issues: Managers manage conflicts and performance concerns; without them, these issues might fester or burden senior leaders.

For all these reasons, Korn Ferry’s CEO Lesley Uren cautioned in that report, “When management disappears, so does direction… A leaner organization today can mean a leadership crisis tomorrow.”

The phrase “leadership crisis” is key. If too much leadership (which middle managers are a part of) is cut out, you risk creating an organization that lacks leaders to step up when needed. Of course there’s the CEO and maybe a few VPs, but they can’t effectively lead hundreds or thousands of individuals. Leaders at every level are necessary. The question is, at what level and how many?

Some companies try to fill this void by creating temporary team leads (someone acts as coordinator on a project but isn’t a formal boss), or using algorithms and OKR (Objectives and Key Results) systems to track work rather than managers, while others distribute managerial tasks among the team—each team member takes turns facilitating meetings, handling admin, etc. These approaches may work in small, highly skilled teams, but it’s challenging to scale universally.

“If No One Wants to Be a Manager, Who Manages?” – The Emerging Leadership Paradox

But there’s a curious paradox arising in tandem with the unbossing trend: many employees, especially younger professionals, lack the desire to become managers. Management roles, which used to be the default path of career progression (“move up or move out”), are now being viewed with some skepticism by Millennials and Gen Z. In 2024, a spate of social media discussions (from LinkedIn articles to viral TikToks) pointed out that “no one wants to be a manager anymore.”

Many employees today hesitate because they perceive managerial roles as ‘high stress and responsibility without proportional increases in pay or job security’—some even describing it as a “glorified unpaid internship.” Stability concerns also arise, as companies frequently eliminate managerial positions first during cutbacks, making individual contributor roles seem safer. Younger professionals, especially, prefer flexibility and autonomy, viewing management duties like meetings and bureaucratic tasks as obstacles to work-life balance. Additionally, alternative career ladders in fields like tech allow progression as individual contributors (e.g., Staff Engineers or Principal Designers) with comparable rewards to management, further reducing the appeal of managerial roles.

This generational shift poses a challenge: who will “manage” in the future? Even if it’s not the initial intention an organization might accidentally end up “flat” because not enough employees are willing to take on management roles. In contrast, companies that are currently unbossing may later struggle to find volunteers to step into leadership positions as needed.

Think about succession planning: how do you cultivate your next set of leaders if nobody wants to lead? One could argue that the traditional management pipeline is being replaced by something else (maybe subject-matter experts who laterally step into leadership when required), but it’s an open question.

For now, companies are experimenting. Some are rebranding managers as coaches or mentors, to make the role sound more appealing and less authoritarian. Others emphasize the purpose and impact managers can have (leading a team to achieve great things) to attract mission-driven young talent into leadership. While others are throwing in the towel and hiring experienced managers from outside since internal candidates are choosing to remain on the side lines. It’s a strange new world where the title “Manager” might be seen as a burden more than a prize.

This paradox illustrates that unbossing is not just a top-down phenomenon (companies cutting managers) but also bottom-up (workers rejecting managerial career paths). The result is a potential gap in the middle that could have lasting implications for organizational resilience.

Do Flatter Organizations Outperform Hierarchical Ones? Academic Evidence

A recurring theme in the unbossing discussion is the balance between autonomy and alignment. Flattening an organization usually increases autonomy by necessity—with fewer bosses breathing down their neck, employees have more freedom (and need) to make day-to-day decisions independently. This can be incredibly empowering. Employees often feel a greater sense of trust from the company (“they don’t need a manager watching me, they trust I'll get the work done”). Autonomy can fuel innovation, as people experiment without having to ask for permission up a chain of command.

However, as I’ve hinted, autonomy’s evil twin is misalignment. With everyone running free, you risk losing the common plot.

This brings me to the question: Do flatter organizations genuinely outperform hierarchical ones?

The research consistently highlights that flatter organizations perform well in fast-changing, unpredictable environments because they can rapidly adapt decisions to new information. For example, Rajan and Wulf (2003) demonstrated that firms in competitive sectors benefit significantly from flatter hierarchies, primarily due to faster decision-making and better resource allocation.

Rajan and Wulf documented a significant flattening of organizational structures within large U.S. firms from 1986 to 1998. Their analysis shows a clear trend toward fewer hierarchical layers, with the number of managers reporting directly to CEOs nearly doubling, and the distance (depth) between divisional managers and CEOs decreasing by roughly 25%. This structural change goes beyond symbolic reorganization, as evidenced by the removal of middle-management roles. Importantly, divisional managers who move closer to the CEO receive notably higher pay and greater long-term incentives, indicating genuine empowerment and delegation of authority alongside organizational flattening.

The paper proposes several explanations for these trends. First, intensified market competition may have driven firms toward flatter hierarchies, enabling faster decision-making, greater responsiveness, and heightened operational agility. Second, improvements in corporate governance—spurred by more active institutional investors and market pressures—may have compelled firms to reduce unnecessary bureaucratic layers. Lastly, advancements in information technology could have facilitated increased managerial spans of control by improving information flow and decision-making capabilities, thus supporting flatter, more streamlined organizations.

Conversely, Adler and Borys (1996) emphasize that formalized bureaucratic structures can enhance efficiency and innovation if implemented in an 'enabling' rather than 'coercive' manner. This enabling approach is particularly beneficial in environments that require consistency, quality control, and scalability, such as manufacturing or regulated sectors, as it provides clear guidelines while supporting autonomy and continuous improvement.

The authors distinguish between two types of bureaucracy—enabling and coercive—based on how formalized rules and procedures are designed and implemented. Enabling bureaucracy provides clear guidelines and procedures intended to support employees in their roles, fostering autonomy, transparency, flexibility, and encouraging active participation and learning. In contrast, coercive bureaucracy relies on strict, rigid controls, designed primarily to constrain employee behaviors, often resulting in reduced autonomy, limited innovation, and lower employee morale. The authors illustrate how enabling structures promote higher employee engagement, innovation, and more positive organizational outcomes, as they empower workers rather than merely control them.

The paper further discusses factors that shape the adoption of these bureaucratic forms, highlighting internal and external influences such as organizational culture, competitive pressures, and management philosophy.

Specifically, organizations facing highly competitive or dynamic environments tend to benefit from enabling bureaucracies. Conversely, coercive bureaucracy is typically prevalent in more stable or strictly regulated environments, where predictability, compliance, and strict accountability take precedence.

Ultimately, Adler and Borys argue that bureaucracy itself is not inherently negative; its impact on performance and employee satisfaction depends critically on its design, implementation, and alignment with organizational context and strategic objectives.

Clear hierarchical structures can also outperform flatter ones during crises. Bigley and Roberts (2001) analyze the Incident Command System (ICS), a hierarchical framework designed specifically for managing complex, volatile emergencies such as natural disasters and hazardous incidents. They demonstrate how the ICS structure supports high reliability through clearly defined roles, authority migration, and systematic but flexible procedures. This hierarchy ensures efficient coordination and rapid decision-making, essential for reliable performance under crisis conditions, by explicitly structuring authority and accountability to reduce confusion and enhance organizational responsiveness.

Overall, research demonstrates no universal superiority of flat or hierarchical structures. Instead, performance outcomes are contingent on strategic alignment with external environments and internal goals. Companies must match their organizational design explicitly with their strategic context and operational demands.

Conclusion: Toward an Unbossed World

The corporate trend of unbossing captures a real zeitgeist: companies striving to be lean, fast, and adaptable in a turbulent world. It’s a pushback against the over-managed, meeting-heavy, slow-decision cultures that many feel have bogged organizations down. By removing layers of middle management, businesses aim to empower individuals, save costs, and break silos.

For business professionals, entrepreneurs, and organizational leaders, the take-home message is balance and intentional design. Flattening an org chart is easy; making it function well afterward is hard.

One must ensure that as formal bosses fade away, the essential functions they served are reimagined—whether through technology, new processes, or cultural norms. Employees should be prepared for greater responsibility and self-direction, while executives should be prepared to roll up their sleeves and be more involved in the day-to-day (or else delegate decision-making widely and trust their people).

There’s also a human element: work is not just an org chart, it’s a social system. People need leadership, recognition, and clarity. An “unbossed” company isn’t a company with no leaders; ideally, it’s a company where everyone is a leader in their own realm and where formal leadership is more coaching than command-and-control. Some companies, like the pharmaceutical giant Novartis, even adopted the term “Unboss” in their culture to mean managers should act as servants and coaches to their teams rather than traditional bosses. That points to a future where the role of manager changes rather than disappears – from taskmaster to mentor.

So, is unbossing a fad or the future? Probably a bit of both. We’ll likely see cycles – companies will unboss to become lean, then perhaps reboss a bit when they need more structure, and so on.

The most resilient organizations will be those that can dial hierarchy up or down as needed, deploying managers where they add value and eliminating bureaucracy where it’s a drag. In the end, it’s not about having no bosses; it’s about having the right amount of bossing—enough to guide and support, but not smother.

As the saying (almost) goes, “structure is good—until it isn’t.” And finding that point is the art that every business must master in the unbossed era.

Hi I'm not seeing AI cause the unbossing wave yet, but from where I sit definitely seeing signs of change....1) LLMs quietly taking on tasks that used to sit with managers e.g explaining documents, distilling strategies, drafting training plans. 2) Expectations of managers to do more and direct less,3) talk of entry level roles being replaced by AI employees, 4) and early conversation about using AI to set goals, and track activity. Implications are beginning to unfold. Nows the time to start reacting .

Love the takeaway that companies should be intentional about org design - something that I've found to be more the exception than the rule.

That said, is there data suggesting that this is actually a trend? All the examples are tech companies who, for years, believed that they should hoover up as many talented people as possible. Are they really responding to macro market conditions or just returning to a sane structure after years of acqui-hiring, etc.?

What I'm more curious about is whether AI will cause an "unbossing" wave. I see a few micro dynamics that could push towards or against this.

1) Learning curve. A key role of managers is to onboard new employees and then develop them. Some of this content is organization specific, but some if general domain knowledge tied to the employee's role. A lot of the more technical learning can be done by LLMs and then refined by a manager. I've found this to be the case in a new role involving a type of project I'd never done before.

2) Managing consultants. In many companies, managers and individual contributors spend a lot of time managing consultants. As AI allows companies to insource part of what consultants do, it may shift time to individual contributors taking on this work and away from managers managing consultants.

3) Tech adoption. People outside of tech have no idea that the vast majority of people are terrible at using technology. It's possible that AI will become a new user interface that let's many employees use technology that they couldn't before (i.e. get the benefits of Excel without learning how to use it). If so, managers may become more important because they'll be needed to process and coordinate more output coming from individual contributors.