A month after the academic year at Wharton has ended, and schools are starting their summer break. What a great time to look back and see how much we’ve progressed… or maybe not:

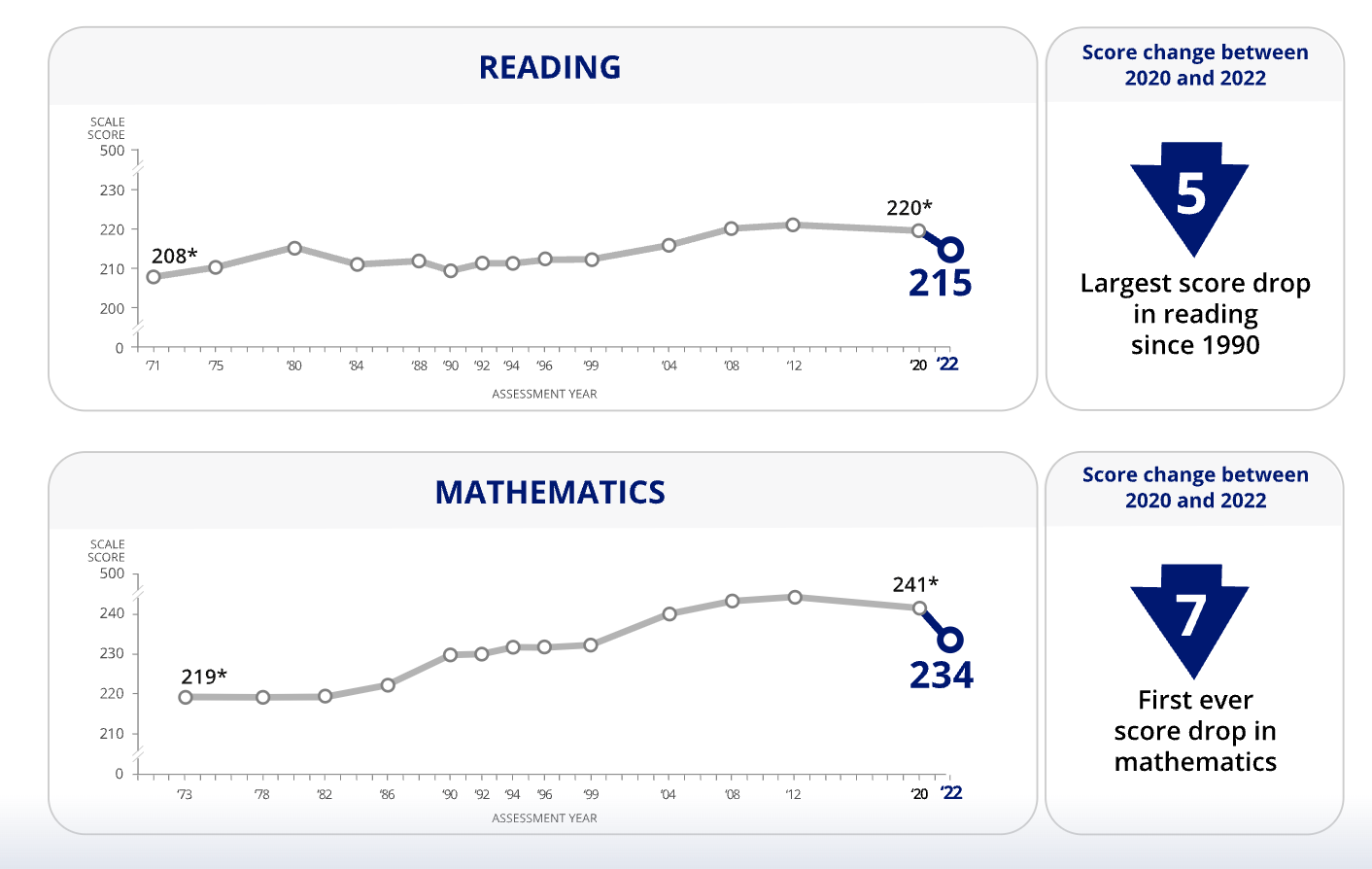

“Test scores known as the Nation’s Report Card, released on Monday, show the largest math declines ever recorded for fourth- and eighth-graders.

Driving the news: Math scores declined for those grades in nearly every state and district between 2019 and 2022, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results. During those COVID years, reading scores also fell in most states, according to the Education Department, which released the scores.

Why it matters: COVID and the resulting school closures spared no state or region. The pandemic resulted in historic learning setbacks for America’s children, erasing decades of academic progress and widening racial disparities, AP reports.

Between the lines: Reading scores dropped to 1992 levels. Nearly four in 10 eighth-graders failed to grasp basic math concepts.”

While I’m not an expert in education (not that I don’t try to pretend to be one by teaching at the Penn Graduate School of Education), the notion of continuous improvement and its quality are topics that operations researchers have spent years pondering and developing methodologies for.

I know the quote above is related to Covid, but the main issue is deeper. Looking at the following graphs, we see a significant improvement in math scores, but not in reading:

And even if we were to believe that kids today are better at math (compared to 1971), is it certain that they are better at math, or are they just better at taking math exams? What’s the root cause for the limited impact of continuous improvement methods in education?

The Missteps of Continuous Improvement in Education

Methods of continuous improvement (lean operations among them) have gained recognition in several sectors as ways to improve efficiency and outcomes. However, the application of continuous improvement in the education sector, though well-intended, has not produced the desired results. There are several reasons why, and by examining certain educational policies (such as the “No Child Left Behind” Act (NCLB) under President George W. Bush and the “Every Student Succeeds Act” (ESSA) under President Barack Obama) we can better understand these reasons.

Firstly, the application of continuous improvement in education has been characterized by an over-reliance on metrics, predominantly standardized test scores. This methodology, borrowed from the business sector, provides easily measurable and quantifiable metrics to gauge success. However, education is more complex, and learning is a multifaceted process that can’t be fully encapsulated by test scores alone.

The NCLB Act, signed into law in 2002, required states to develop ways to assess students’ basic skills in certain grades to receive federal funding. While the intent was to measure and improve academic achievement, the act inadvertently drove responsible bodies into gaming the system. In order to meet the requirements set by the law, schools and teachers began teaching to the test. As a result, while test scores improved, the focus on broader educational goals, critical thinking skills, and comprehensive learning was often undermined.

Similarly, the ESSA, signed into law in 2015, aimed to ensure success for every student by holding schools accountable for student performance. However, while it provided more flexibility than the NCLB, it still relied heavily on standardized test scores as a key metric for school performance. Although it added multiple metrics of student success to the accountability systems, these were often overshadowed by the focus on test scores.

Secondly, the lag between action and results poses a significant challenge. In business, this process relies on rapid feedback cycles where the results from certain changes show immediately. However, changes in education policies or teaching methods can take years, or even decades, to show their full effect. This long feedback loop makes it difficult to accurately evaluate the success of lean-inspired initiatives in the education sector.

The NCLB and ESSA both suffered from this problem: While test scores initially increased, suggesting a positive impact, the long-term outcomes were less clear. Numerous studies suggest that teaching to the test does not lead to genuine improvements in education and can even be detrimental to students’ broader education.

The situation in higher education is similar:

“Our literature review identified numerous case-based examples of organizational improvements that have benefitted academic and administrative operations. However, compelling, evidence-based conclusions of the overall impact and effectiveness of LHE initiatives are missing from the current body of literature. The groundwork certainly has been established for the development of conceptual frameworks to further guide LHE initiatives. Such frameworks, together with further integration of organizational development and change management literature, will define best practices when implementing LHE locally and throughout the institution.”

Not All Continuous Improvements are the Same

A significant critic of continuous improvement methods, particularly those implemented in grade school, was W. Edwards Deming —an American engineer, statistician, professor, author, and management consultant, mostly known for his work on quality management.

Deming is best known for his work in Japan after World War II, and particularly his contributions to the country’s phenomenal post-war economic success. He introduced quality control methods and concepts that transformed the Japanese industry and have since been applied in various industries around the world. One of Deming’s main contributions is the “Deming System of Profound Knowledge,” and although his principles were primarily applied to manufacturing, his theories have had a profound impact on education.

Deming himself wrote quite a bit about education so it’s not surprising that the institute that carries his name criticizes the current efforts:

“Educators have become wary of people who want to apply business approaches to improve education. They have experienced 15+ years of federally led policies such as No Child Left Behind Act (2002) and Race to the Top (2009) which tied financial incentives to school improvement. During this period, they have seen approaches like performance-based pay and bonuses fail. An over-emphasis on testing and implementing standards has consumed students’ precious classroom time without really affirming whether students are learning how to think. Teachers are leaving the profession because their expertise and creativity are not being respected.”

Deming’s approach focuses on systems thinking, continuous improvement, and viewing education as a system that requires cooperation and collaboration rather than competition. He believed that an over-reliance on numerical quotas, such as test scores, only serves to undermine quality, as it forces teachers to “teach to the test” rather than focus on comprehensive, quality education. Deming argued that most problems in a system stem from the system itself, not from individuals within the system. Thus, the focus should be on improving the system.

In the context of education, applying Deming's principles would suggest a few key changes:

Abandoning the focus on numerical quotas: Instead of focusing on easily gameable metrics like test scores, a Deming approach to education would emphasize qualitative feedback, self-assessment, and holistic student development.

Enhancing cooperation and reducing competition: Deming believed that competition within an organization or system often leads to decreased performance. In an educational context, this might mean promoting more collaborative learning environments and less competitive grading systems.

Fostering a culture of continuous improvement: This includes encouraging educators to be lifelong learners and to continually experiment with and refine their teaching practices.

Looking at the system, not just the individuals: Instead of blaming teachers or students for poor outcomes, a Deming approach would look at the entire education system to identify areas for improvement. This might include everything from classroom size and resource availability to curriculum design and administrative policies.

Applying Deming's approach to education would represent a significant shift from current practices, especially in systems that heavily emphasize standardized testing and competitive grading.

A Success Story

One of the most successful examples of applying the concepts of continuous improvement in education is the Long Beach Unified School District (LBUSD) in California, USA.

Long Beach is the third-largest school district in California and serves a diverse student population. Despite the challenges associated with this, LBUSD has consistently outperformed other similar districts in terms of student achievement.

The district’s approach aligns closely with the core principles of continuous improvement and the key to their success has been a strategy that emphasizes collaboration, data-driven decision-making, and a systemic approach to change.

Collaboration: LBUSD places a strong emphasis on collaboration at all levels. Teachers are encouraged to work together to develop and refine teaching strategies, while administrators work closely with teachers, parents, and the community to identify needs and develop solutions.

Data-Driven Decision-Making: Like many continuous improvement strategies, LBUSD's approach is heavily data-driven. The district regularly collects and analyzes a wide range of data, including test scores, attendance rates, and other indicators of student achievement and well-being. This data is used to identify areas for improvement, develop action plans, and monitor the effectiveness of changes.

Systemic Approach to Change: Rather than focusing on individual teachers or schools, LBUSD takes a systemic approach to change. The district recognizes that many of the challenges it faces are systemic in nature and therefore require systemic solutions. This means looking at the entire system — from classroom practices to administrative policies — to identify and address areas for improvement.

Let’s stay on this last one a little longer to make sure we truly understand the approach. So rather than focusing on individual teachers or schools that might exhibit high absentee rates, LBUSD understands that student absenteeism might not be a function of what’s happening in a specific classroom or school, but could be influenced by a myriad of interconnected factors across the entire educational system such as:

Classroom Practices. Are engaging and relevant teaching methods being used to make students want to attend class? They would examine if teacher training programs emphasize student engagement and if they are equitably implemented across the district.

Administrative Policies. Are the policies around absences punitive or supportive? Is there a district-wide policy that understands and addresses the reasons why students might be missing school, such as health issues, transportation problems, or family troubles?

Systemic Socioeconomic Factors. Are there social services in place to support families in crisis? Is there adequate public transportation for students to get to school? Are there after-school programs to provide safe spaces for students until working parents return home?

Over the past two decades, the district has seen significant improvements in a range of areas, including higher test scores, lower dropout rates, and increased college readiness among students:

“Long Beach Unified School District (LBUSD) is a leader in the state of California in supporting student achievement, especially for students of color and students from low-income families. From 2015 to 2017, LBUSD’s African American, Latino/a, and White students consistently outperformed students in other districts with similar economic backgrounds on California’s new state assessment.1 (See Appendix A.) Moreover, the district’s students tend to graduate at higher rates and drop out of school at lower rates than the average California student.2 (See Appendix A.) Although most Long Beach students still do not achieve proficiency on the state’s standardized tests, LBUSD’s recent track record suggests that the district’s educators and leaders have been successful in supporting more rigorous instruction under California’s Common Core State Standards (CCSS), which were implemented in 2010.”

Deming and Lean

You know I’m a fan of lean operations… But did you know that Deming was, in fact, what inspired the Toyota production system? And while lean operations and Deming’s approach both aim at business improvement, their focus and methodology differ. Lean aims to eradicate all forms of waste (i.e., anything that doesn’t add value to the customer) through tools like Value Stream Mapping and Kanban. Deming’s approach is centered primarily around quality improvement via a continuous feedback loop known as the Deming Cycle or PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act). Deming’s model often utilizes statistical process control to monitor processes and spot variations.

When applied to education, Lean might involve streamlining administrative processes, reducing waste in resources, and ensuring that all activities are centered around student learning, leading to more efficient educational delivery. For example, Lean might seek to minimize waiting time for students between classes or to reduce redundant teaching materials.

On the other hand, Deming’s approach would emphasize constant quality improvement of the learning process, aiming to provide students with the best possible experience. This would involve continually evaluating and refining teaching methods based on feedback and outcomes and always aiming for a higher standard.

So Why is Improving Education so Difficult?

A fundamental principle here is the concept of “quality at the source.” I’ve previously discussed this in healthcare, so how am I applying it in my own professional life as a professor, rather than just recommending it?

Education is challenging, and surprisingly enough, in education, we often do the opposite of implementing “quality at the source.” This may be because pinpointing the source of quality is complicated since the improvements come into effect with the lag I mentioned above.

My teaching evaluations usually come in at the end of the semester, and while some feedback is easy to comprehend and some is disheartening, as I sift through it and try to decide what to adjust, I realize that these changes will only affect future students, and to that extent, they’re not really “at the source.”

Therefore, today my goal is to contemplate ways to apply the principle of “quality at the source” in high-stakes fields like education, and potentially discover methods to implement it. The ensuing conversation revolves around the implications of “quality at the source” in various contexts - how can we ensure continuous improvement of a product’s quality by eliminating common errors and problems?

“Quality at the source” implies ongoing assessment, for instance, evaluating each participant’s contribution. In recent years, I’ve incorporated the concept of ‘exit tickets’ at the end of each week, asking students about their key takeaways or improvements. However, the reality is that many suggestions, like ‘improve my handwriting,’ are things I can't really amend.

Quality at the Source Requires Measuring … Quality

In the world of high school, there is standardized testing. What about our world, the higher-ed, when these do not exist?

How would you measure quality in this case?

We use Teaching evaluations. Teaching evaluations, typically in the form of student surveys, are a tool intended to measure an instructor’s effectiveness and are often used to guide decisions about tenure, promotion, and salary raises. Theoretically, these evaluations provide valuable feedback that can guide a teacher’s continuous improvement and inform institutional changes. They highlight strengths in teaching methodology, provide insights into areas that need enhancement, and reveal students’ perceptions of the learning environment.

However, while the intention behind teaching evaluations is commendable, their application has faced significant criticism, and their efficacy in genuinely promoting continuous improvement has been called into question for a few key reasons, such as:

Bias in Evaluations: Research has shown that teaching evaluations can be influenced by factors unrelated to teaching effectiveness, such as the instructor’s gender, ethnicity, attractiveness, or even the time of day the class is held. This bias can skew the results of evaluations and lead to inaccurate assessments of one’s teaching ability.

Focus on Popularity over Quality: Teaching evaluations might inadvertently prioritize instructors’ likability over their effectiveness. An engaging instructor who is lenient in grading might receive higher evaluations than a more rigorous instructor who challenges students to think critically and pushes them to achieve their best.

For example, the course I teach is a case-based course, where certain knowledge is only obtained once students do the court case. So I was very disappointed when I received the following comment:

“I walked away after class not knowing what we had talked about. I don’t understand reading a case, doing an assignment based on the case, then learning how to do the case. In my entire educational and professional experience I have learned a fundamental skill/topic then applied it. In this class it is the opposite which leads to little learning and lots of confusion.”

Now don’t get me wrong. This specific class had very good teaching evaluations (around 3.9 out of 4) but the specific comment was extremely disappointing, mainly because the core of “quality at the source” is to ensure that only students who are willing to do certain things should take the course.

In other words, I’m not claiming that the class can’t be improved, but sometimes we have to acknowledge that “we’re not the right customer for this service.”

When I teach MBAs and undergraduate students, I have a very strict tardiness policy. Class starts a minute after the official start time, but when I start, if you are not seated, (and unless you email me in advance with reasons around flight delays, or interviews), you can’t come in. My rationale: the classroom is a “sacred” place where learning happens only if everyone is committed to learning from the first minute to the last. I tried many things and have converged on it. I usually have to dismiss a few students who attempt to bend the rules. By the end of the semester, most students agree that this is a good policy. But I always get one or two comments that are extremely negative. In fact, a colleague recently shared that they were unable to implement such a policy in fear of receiving lower scores in their teaching evaluations.

So while teaching evaluations aim to (and can) improve teaching, they can also reinforce “popular” policies rather than good policies.

Over-reliance on Quantitative Measures: Much like standardized test scores, teaching evaluations often emphasize easily quantifiable measures, such as numerical ratings, at the expense of qualitative feedback. This narrow focus can oversimplify the multifaceted nature of effective teaching and learning.

Low Response Rates: Often, students who choose to complete teaching evaluations represent a small fraction of the class and may not accurately represent the views of all students. This can further skew results.

For all these reasons, teaching evaluations have often failed to produce the intended outcomes in the context of continuous improvement. They may not accurately reflect teaching quality, can perpetuate bias, and may encourage teaching practices aimed more at popularity than at deep, effective learning.

However, this does not mean that the concept of teaching evaluations should be abandoned entirely. Instead, it suggests a need for a more thoughtful approach to their design and implementation. This might include providing structured guidelines for qualitative feedback, ensuring anonymity to mitigate fear of retribution, and offering training to educators on how to interpret and apply the feedback they receive. Additionally, teaching evaluations should be considered as part of a broader set of measures used to assess teaching effectiveness rather than the sole indicator.

The Root Cause

So ultimately, “quality at the source” is easily applied in manufacturing and can easily be applied in healthcare, but it’s actually not that easy in a setting that’s not purely linear. Education is a process where there’s co-creation of value between the student and the teacher, and determining quality, even in the long run is not trivial.

And that’s maybe my conclusion.

I like to do more “quality at the source” and I would like to do more mistake proofing, but for that, we have to do more root cause analysis.

Here is one example. A few years ago I taught a course at the end of which students had to work on a project with a firm. The main problem was that the students’ satisfaction and the learning from the project were relatively uncertain. All firms were happy to work with the students but while some problems were solved without the need for much depth, there were other cases where things changed mid-way resulting in a firm’s inability or unwillingness to cooperate (management changed in one case, or entering M&A in another). Since this process took place at the end of the course, it loomed large on the overall satisfaction of the course. The solution was to eliminate the project and create another course that was only project-based. We had to redesign the course to add elements that were missing now without the project and had to put a whole administrative function to help and manage the project-based course, but the main process of continuous improvement was analyzing the source variation and realizing that we cannot control it for the scale of that course.

Returning to the comment from the student on the case-based discussion, my root cause analysis brought me to the following steps:

Examine where I need to provide more explanations before the session to ensure students feel they had the necessary tools

When that’s not possible, I must make sure it’s clear why (if this is the right pedagogy) to ensure we increase learning

Make sure students are aware of the fact that this is a fairly case-based class. And if they don’t like it, then maybe it’s not the right class for them. After all, this is an elective.

So, this article is not to say that we can’t use continuous improvement tools in the classroom or in education in general, but that one of the most fundamental concepts is difficult to implement as is… which is a shame.

But this also brings me to what I find the most alarming aspect of the degradation in quality tests in reading and math. If people don’t know how to read and don’t know math, I can only do that much to take them to the next level. People that don’t know how to learn, will find it very hard to … learn.

In conclusion, while continuous improvement methods have been beneficial in certain sectors, their application in education has proven challenging. Our love of numbers and test scores has led to a narrow focus on specific areas of learning, often at the expense of a more comprehensive education. Moreover, the long lag between the implementation of education initiatives and their outcomes makes it difficult to assess whether these policies are successful or not.

To improve the application of continuous improvement methods in education, it’s necessary to find more comprehensive and nuanced ways to measure student achievement and cultivate patience for long-term results. The education sector should also adapt continuous improvement principles to its unique context rather than attempt to directly replicate business models. This way, the intent behind lean operations – reducing waste and increasing efficiency – can be more effectively realized in education.

Excellent, any other resources I can refer to