The Most Evergreen Forecast: Your Flight will be Delayed

Last week, a report from Congressional investigations revealed that the surge in flight cancellations during the pandemic recovery period was primarily caused by factors within airlines’ control. These factors included cancellations due to maintenance issues or a shortage of crew.

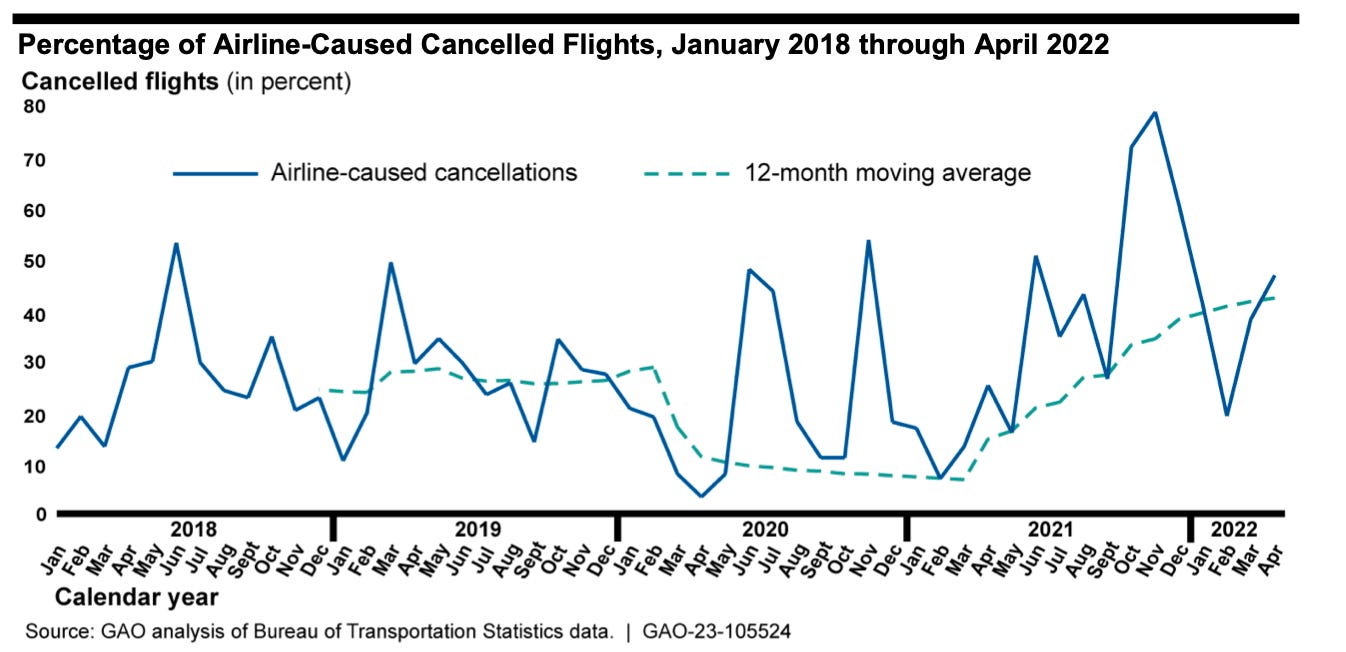

“The GAO said that weather was the leading cause of cancellations in the two years before the pandemic, but the percentage of airline-caused cancellations began increasing in early 2021. From October through December 2021, airlines caused 60% or more of cancellations — higher that [sic] at any time in 2018 or 2019.”

As evident from the following graph, there’s definitely some seasonality, but even after taking this factor into account, looking at the 12-month average, airline-caused cancellations are more:

According to the same report, in 2019, Hawaiian Airlines and Alaska Airlines had the highest percentage of cancellations ‘due to airline-controlled issues,’ accounting for more than 50% of each airline’s total cancellations. However, in late 2021, low-cost carriers Allegiant Air, Spirit Airlines, JetBlue Airways, and Frontier followed suit, with each airline responsible for 60% or more of their total cancellations.

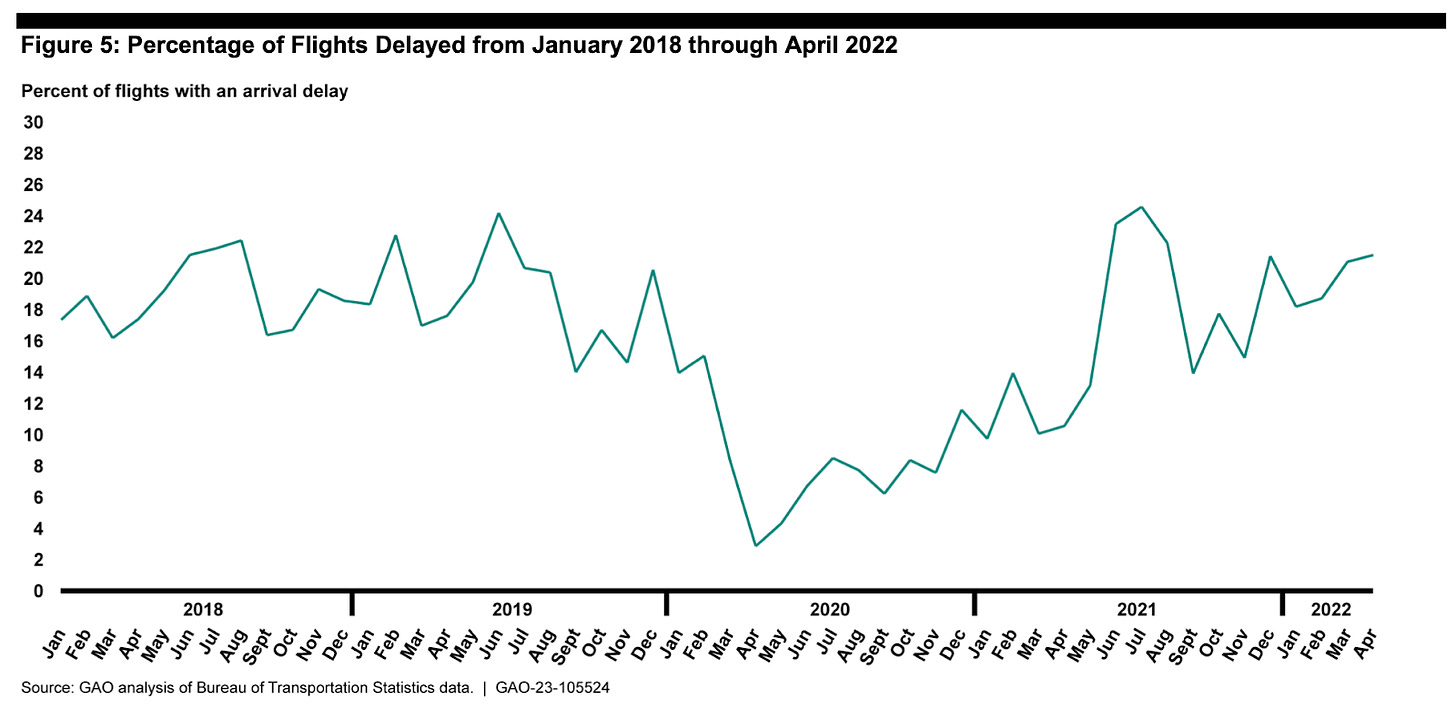

And it’s not only about cancellations; it’s also about delays. Almost all airlines had more airline-caused delays during the studied period than before that.

Since the analysis above is past-oriented, you may wonder what it tells us about the future, particularly the upcoming summer travel season.

I predict that we will experience significant travel delays this coming travel season. Whether it will be worse than before the pandemic will depend on how bad the weather disruptions will be. If they persist, it’ll be worse… much worse.

This is just an evergreen prediction, but I honestly think it’ll be worse.

Why?

Because some of the actions the airlines are taking to solve these issues … may actually end up making them worse.

What are Airlines Doing?

So let’s talk about what the airlines have decided to do to combat the issues discussed above:

“‘Carriers have taken responsibility for challenges within their control and continue working diligently to improve operational reliability as demand for air travel rapidly returns,’ said the spokeswoman, Hannah Walden. ‘This includes launching aggressive, successful hiring campaigns for positions across the industry and reducing schedules in response to the FAA's staffing shortages.’”

With the Federal Aviation Administration experiencing severe shortages in air control staff at a key facility in Long Island, several airlines have agreed to reduce schedules in New York this summer, and fly fewer and larger planes.

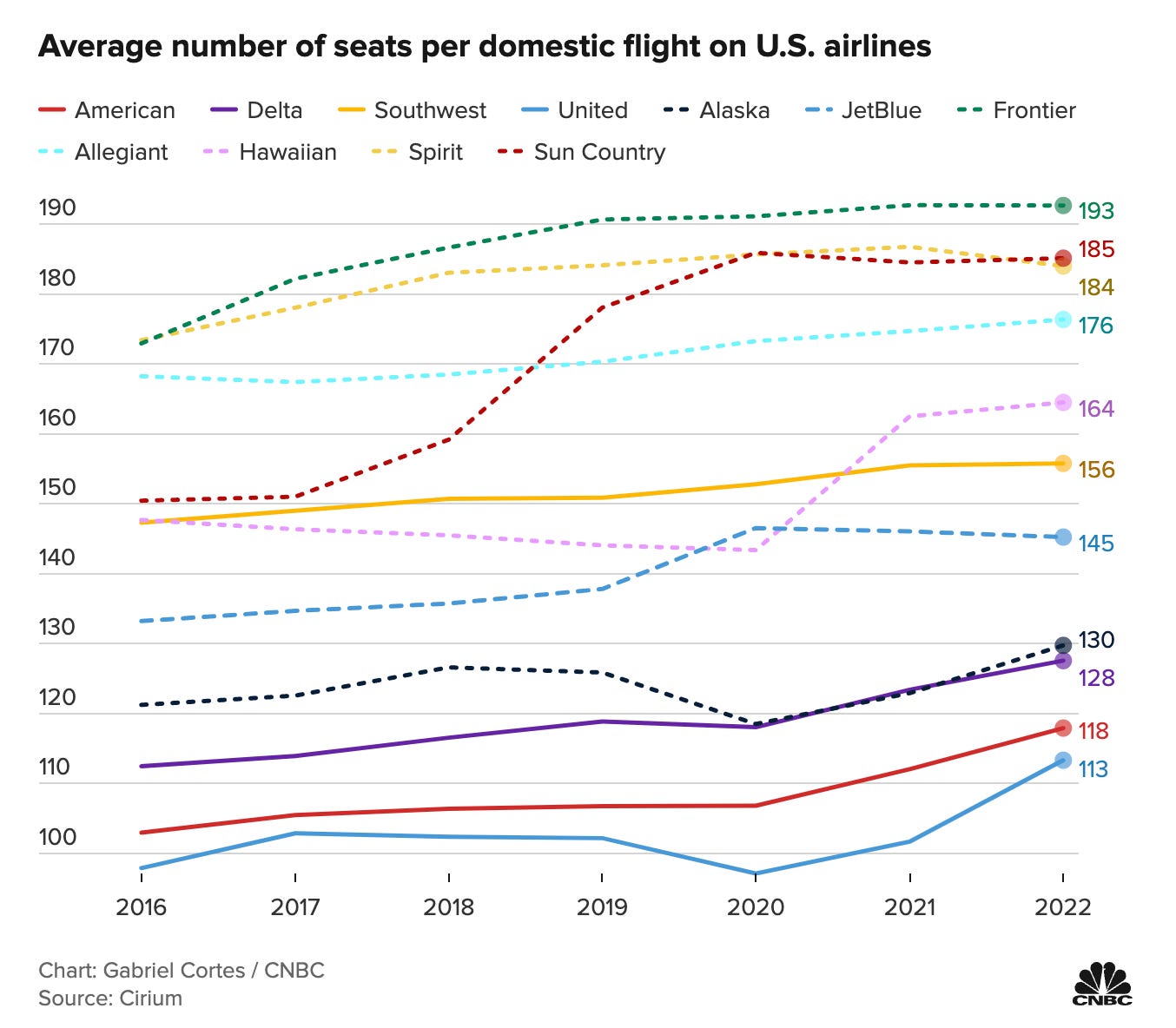

For instance, compared to 2019, United Airlines increased the seats per departure in its full network by 20. This trend toward larger planes, particularly during times of anticipated peak travel, has become more pressing in light of the shortages in pilots, air traffic controllers, and new aircraft:

“Keeping the operation running smoothly at crowded Newark is key, United vice president Cox said. If planes don’t take off fast enough on schedule, because of limited numbers of gates ‘you’ll see it turns into a parking lot,’ he said.”

Airlines are cutting flights at Washington’s Reagan National Airport and airports serving New York City to avoid disruptions. United Airlines reduced its New York and Newark peak daily departures and trimmed service from the New York area to Washington D.C. Despite this, the carrier still plans to operate 5% more seats at those airports than in the corresponding month of 2019. The airline claims that less than 2% of customers are expected to be affected.

Sounds great.

Right?

Well, the trend of increasing the number of passengers on planes started before the pandemic and much earlier than these disruptions:

According to Cirium, an aviation data firm, flights operated by the 11 largest US airlines had an average of over 153 seats on domestic flights in 2021 (up from nearly 141 seats in 2017). Despite operating 10.6% fewer flights in April 2022 (compared to April 2019), US carriers had 0.6% more seats in their domestic schedules due to the larger plane trend, also known as “upgauging.” This strategy allows airlines to sell more seats per flight utilizing fewer planes.

And if we dig deeper, it’s clear why airlines like this trend. Reducing the number of flights and increasing the number of passengers per flight solves the central problem of the pilot shortage, allows the airlines to reduce their operational costs, and reduces congestion at airports (in terms of landing slots, and gate slots). It also allows them to increase prices.

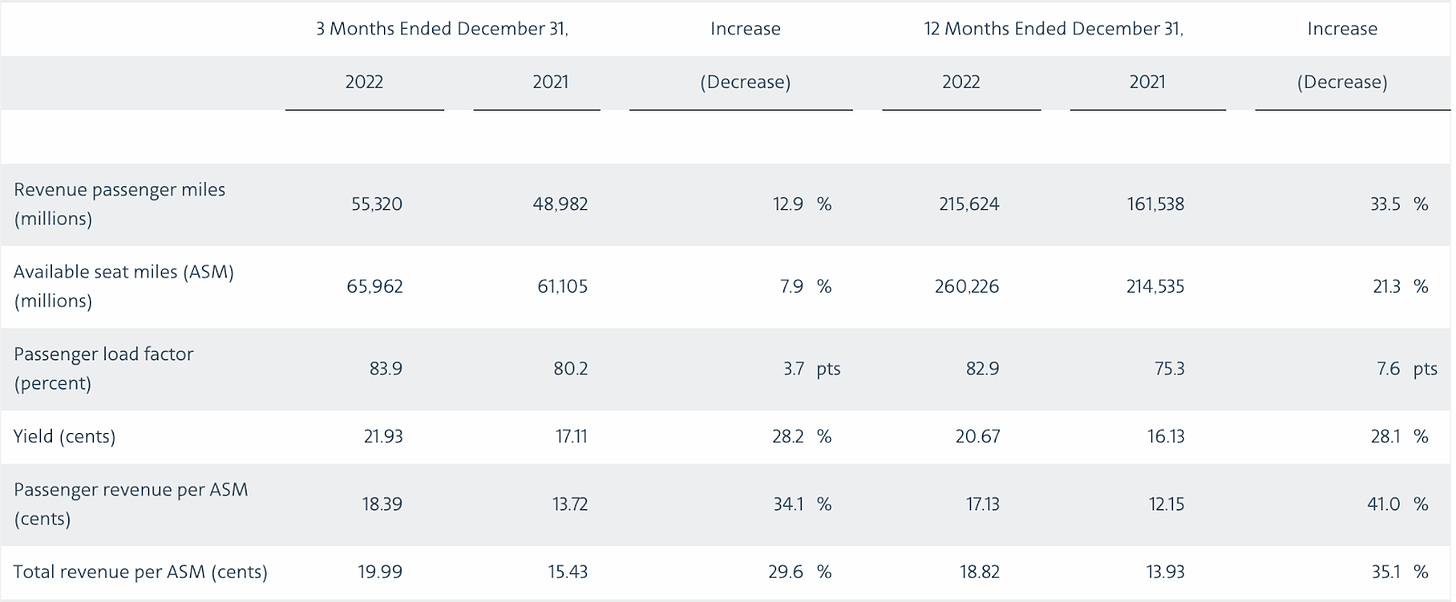

Curious about this last aspect, I checked American Airlines’ financial data:

We can see that compared to 2021, airlines increased their Available Seat Miles by 21.3%, the Revenue Passenger Miles (seat miles with an actual passenger generating revenue) increased by 33.5%, resulting in an increase in yield (the amount of money, on average paid for each Revenue Passenger Mile) by 28.1%.

Just to be clear: airlines have had it tough for a while. Compared to other modes of transportation, in terms of their revenue per passenger mile, airlines are among the lowest and have been declining since 2012, whereas the rest of the modes have been increasing all these years:

Cancelling flights and flying bigger planes may allow them to reverse this trend.

The Trend is Clear

But bigger airplanes with fewer flights also mean a higher load factor (a plane utilization metric). In the previous table which shows AA’s financial data, we can see that the load factor is increasing. But this isn’t a recent trend for US carriers.

And as the workload increases, we should expect more delays (based on the GAO report):

So as planes become bigger and flight options are curtailed, weather issues will impact more passengers as the schedule becomes more concentrated. This will result in more congestion at airport security checks as the schedule won’t be as evenly distributed throughout the day. From a consumer perspective, all this will drive prices up.

So the crux of the matter is that airlines are not a very profitable business and it’s hard to expect good service. And I’m not referring to the quality of airplane coffee (…I've given up on that), I’m talking about trying to be on time when the main concern is the ability to survive without government assistance.

Airlines are not always profitable, and when they are, their profitability is razor-thin.

If we look at the Dollar per Available Tonne Kilometer metric (as a measure of cost) and the Dollar per Revenue Tonne Kilometer metric (as a measure of revenue), we can see that both have been decreasing while maintaining a very narrow margin between them:

Looking at the actual profitability, we can see it’s not a pretty picture:

And things are worsening in terms of labor costs:

In an environment like this, we can’t expect much from airlines:

“Moody’s projects combined revenue for the eight airlines—namely, United, Delta, American, Southwest, JetBlue, Spirit, Hawaiian, and Allegiant—to reach $212 billion this year, or 13 percent higher than the $187 billion they generated in 2022. While the companies continue to experience strong demand through the summer, capacity shortfalls brought on by shortages of aircraft, spare parts, maintenance capacity, and labor will help support ticket prices well into 2024, even if a recession takes hold and slows demand, said the report’s author, Moody’s Investors Service senior v-p Jonathan Root. Still, the price elasticity of demand over economic cycles will prove what he called the ultimate arbiter of the industry's ability to cover increasing costs.”

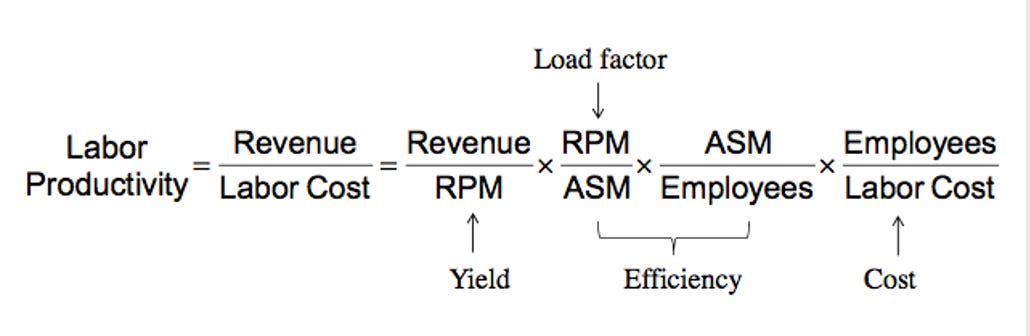

Airline economics are simple:

So, it’s clear that airlines want to increase their load factor and reduce their costs while increasing their yield. And as labor costs continue to increase (ChatGPT may replace some jobs but it’s not replacing flight attendants any time soon), the ability to increase both the load factor and the yield may prove crucial for airlines.

Fewer options – fuller planes – more expensive tickets and longer delays.

Where do I sign up?

What can the Government do?

But you may wonder what the regulator can do (based on the GAO report):

“The GAO said the Transportation Department has increased its oversight of airline-scheduling practices. The Transportation and Justice departments are investigating whether Southwest scheduled more flights than it could handle before last December's meltdown. The Southwest debacle has led to calls to strengthen passenger-compensation rules.”

Remember the dashboard the Department Of Transportation introduced to ensure compliance with refunds related to delays and cancellations?

Curious whether it actually helps, the paper Can consumer rights improve on-time Performance? Evidence from European Air Passenger Rights studied this exact issue, albeit within a European context. The conclusions:

“Under EU Air Passenger Rights legislation (“EC261”), carriers must provide assistance and cash compensation to passengers in case of long delay. We study whether the regulation reduces flight delay. EC261 applies uniformly to flights departing from the EU, but covers only EU carriers on EU-bound flights. Exploiting this variation, we find that regulated flights are 5% more likely to arrive on time, and mean arrival delay is reduced by almost four minutes. The effect is strongest on routes with little competition, and for legacy carriers. Thus, consumer rights can improve quality when incentives from competition are weak.”

So, the regulator can help, particularly in situations where there is less competition.

So maybe the answer is to increase competition:

“Today, four airlines—American, Delta, United, and Southwest—control 80% of the market and the airline industry is smaller and more concentrated than at any time since 1914, says William McGee, a longtime Consumer Reports editor who is now a senior fellow for aviation and travel at the American Economics Liberties Project. The promise that deregulation would allow new airlines to enter the marketplace and compete has fallen flat too; until 2021, when Breeze Airways started operations, the market had gone 14 years without a new entrant, he says.”

And indeed, there is evidence that increased competition may result in better service. Mike Mazzso (a former colleague at Kellogg and the succeeding Dean of Washington University in St. Louis) shows that this indeed might be the case:

“Analysis of data from the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics in 2000 indicates that both the prevalence and duration of flight delays are significantly greater on routes where only one airline provides direct service. Additional competition is correlated with better on-time performance. Weather, congestion, and scheduling decisions also contribute significantly to explaining flight delays.”

But creating additional competition is not trivial, especially when we consider the unattractive airline economics and the significant barriers to entry. To make matters worse, there’s actually some evidence suggesting that increased competition may result in worse delays.

But in their paper The Effect of the Internet on Performance and Quality: Evidence from the Airline Industry, Ater and Orlov argue that that may not be the case:

“How did the diffusion of the Internet affect performance and product quality in the airline industry? We argue that the shift to online distribution channels has changed the way airlines compete for customers - from an environment in which airlines compete for space at the top of travel agents’ computer screens by scheduling the shortest flights, to an environment where price plays the dominant role in selling tickets. Using flight-level data between 1997 and 2007 and geographical growth patterns in Internet access, we find a positive relationship between Internet access and scheduled flight times. The magnitude of the effect is larger in competitive markets without low-cost carriers and for flights with shortest scheduled times. We also find that despite longer scheduled flight times, flight delays increased as passengers gained Internet access. More generally, these findings suggest that increased Internet access may adversely affect firms' performance and firms’ incentives to provide high quality products.”

And the rationale is clear. If an organization is barely making money, everything is a tradeoff: if you need to compete on prices, you will forgo all the different tools you have to make sure you are on time.

And just to be clear, it’s true that you get what you pay for:

“In recent years, low cost and ultra low cost carriers have expanded significantly to be an important part of the airline industry. Little research has been conducted considering low cost and ultra low cost carriers as two different types. This paper seeks to analyze the product quality of flights operated by these two distinct types of carriers comparing to legacy carriers and whether the presence of these carriers improve overall flight quality. Empirical results suggest that while flights operated by low cost carriers’ on-time performance is slightly worse than legacy carriers, ultra low cost carriers delay much more. In addition, the presence of these types of carriers in an airport also have positive effect on the punctuality of flights departing from that airport.”

So what can you do?

Pay more, choose a competitive route, and as usual: make sure you have enough reading material with you. My crystal ball tells me you may be spending more time in the airport than you initially planned.