About a week ago, Bloomberg published an article about the impact of fast fashion waste on developing countries. I’ve written about the impact of the culture of returning products before, focusing on the number of products we buy online and return, as well as the fact that many of these products, instead of being repurposed or reused, find themselves (even when they are brand new) in landfills.

But landfills are not only filled with clothes that were returned unworn, but also with clothes that just reached their end-of-life and were thrown away. And this is where the focus of the Bloomberg article lies:

“Each year the fashion industry produces more than 100 billion apparel items, roughly 14 for every person on Earth and more than double the amount in 2000. Every day, tens of millions of garments are tossed out to make way for new, many into so-called recycling bins.”

According to the article, the main issue is that old clothes rarely get recycled. The process is too expensive and the technology is not yet adequate. And while there is a global supply chain which deals with second-hand clothing (turning them into rags or stuffing), given how cheap it’s become to manufacture clothing these days, it rarely makes sense to repurpose them.

The real tragedy is that this isn’t about items that customers returned just because they weren’t a good fit. These are products that were returned by customers who thought they were doing something good:

“In early 2013, H&M became the first major retailer to start a global used-clothing collection program, setting up bins at thousands of stores in more than 40 countries. … ‘Everybody wins!’ the company said on its blog. ‘H&M will recycle them and create new textile fibre, and in return you get vouchers to use at H&M.’ Other big fast-fashion chains, Mango, Primark and Zara, followed suit with their own campaigns.”

Well, in reality, it would seem that not everybody wins.

“What none of the campaigns acknowledge is that industrial-scale recycling of used textiles into new clothing doesn’t yet exist. Globally, less than 1% of used clothing is actually remade into new garments, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a UK nonprofit (in contrast, 9% of plastic and about half of paper gets recycled).”

The article describes the labor required to sort these items and the hardship the workers suffer, as well as the environmental impact of these massive landfills. Of course, not all of this is related to the fast fashion industry pioneered by Zara and H&M. Still, the article focuses on two main impacts of the fast fashion industry:

The overuse of new materials, which are also less recyclable.

The increase of clothes in volume and complexity, and the impact on labor conditions in developing countries.

And while the article provides many facts and numbers, its focus on the end-of-life impact of the apparel supply chain may be a bit misguided or even misleading.

Life Cycle Analysis

In order to truly understand the environmental impact of the fashion industry, and in particular, the fast fashion industry, we have to look at the entire life cycle of the product.

This is how the generic life cycle of clothing looks:

There are different ways to divide a life cycle, but most scholars focus on the following stages:

Raw Material Extraction,

Fabric Manufacturing,

Clothing Manufacturing,

Retailing (which includes distribution and warehousing),

Use (including transporting the products to the customer, and treating the product after every use), and finally,

End-of-life Stage (which is where Bloomberg focuses).

This research paper aims to collect information and understand the impact that different fabrics in different stages have, along with their environmental impact. As you can imagine, there is a lot of information, so the paper identifies seven categories of impact (per kilogram) on three environmental aspects: greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), energy footprint, and water footprint.

Group 1 has minimal impact on the environment: no GHG, and little to zero energy and water usage. Group 7 has a massive impact of GHG and significant usage of energy and water.

I’m not presenting all the results from the paper, but the following summary chart shows which life-cycle stages include what type of harm (which may vary depending on the specific fabric or processes used).

We can see that the main stages with the highest potential for harm are not End-of-life, but Material Extraction (in terms of energy and water) and Use (in terms of GHG and energy).

Let’s start with the Material Extraction stage. The article presents evidence that Indian silk fiber production causes the highest environmental impact (causing 80.9 Co2Eq/kg of GHG, requiring 1858 MJ/Kg of energy, and 54,000 L/KGg of water). On the lower end of the spectrum, Tencel (made from sustainably sourced wood) causes only 0.05 Co2Eq/kg of GHG, and has a footprint of 65 MJ/Kg energy and 263 L/Kg water. Surprisingly, polyester causes 3.1 Co2Eq/kg of GHG, and 53.64 MJ/Kg energy (and no water). Wool made in the US causes 18.5 Co2Eq/kg of GHG, and nothing else —limited impact compared to silk and other fibers.

The Use stage, which is the key stage in terms of its adverse impact (as shown above), varies by the type of washing, drying, ironing, and dry cleaning needed. A regular efficiency washer with efficiency drying, causes 51.57 of Co2Eq/kg of GHG, requires 232.75 MJ/Kg of energy, and 1116.63 L/Kg water (all per 45 cycles). Dry cleaning requires a similar level of energy, but has less GHG and no water use. Ironing requires around 400 of MJ/Kg.

So what about the End-of-life stage? The paper provides the following table:

In other words, Sorting is the only meaningful activity, and the overall impact on the environment is relatively minimal when compared to the earlier stages. In fact, some activities, such as Reuse, have a negative impact on GHG.

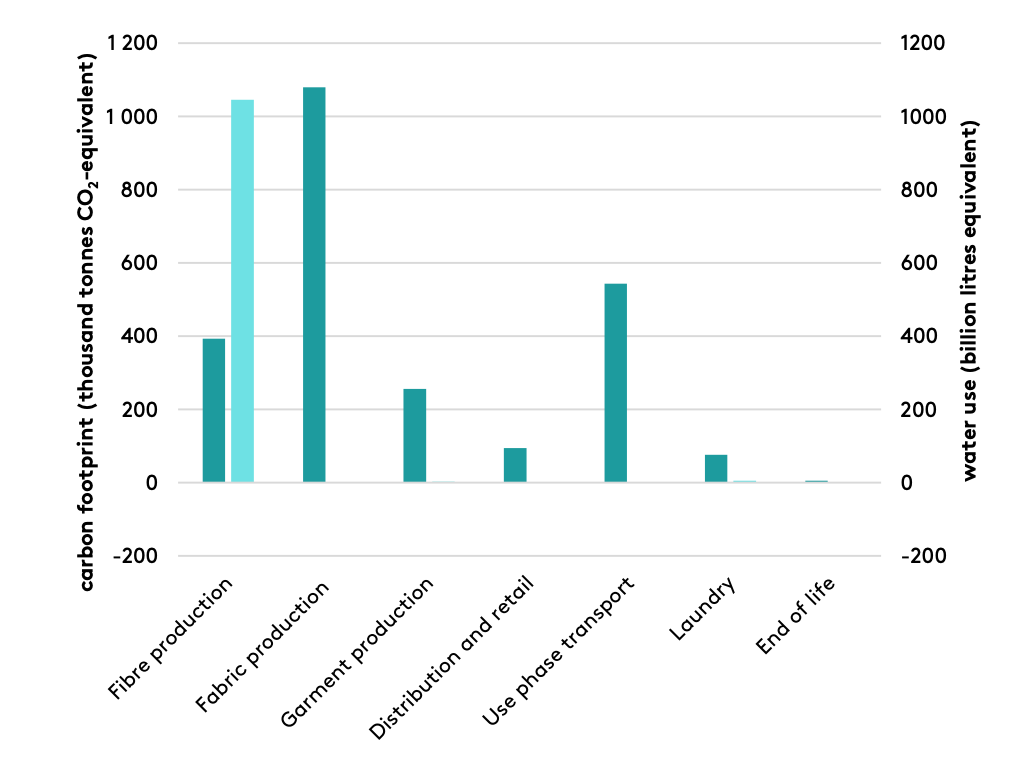

In a somewhat related study, which is also cited in the previous paper I mentioned, the authors looked specifically at the Swedish industry and found similar results:

The graph above shows that Fabric production is the worst stage, and the Use phase transport (delivering products from the store or distribution center to the customer) follows closely. In this study, Laundry and End-of-life are small in comparison.

Note that the reason transportation is so much higher in the “Use” stage (compared to any other stage) is the lack of scale economies —we transport one item at a time.

Can Anything be Done?

An important action to reduce the environmental impact of this industry is to extend the product’s life:

But you can see that that alone isn’t enough. The biggest impact comes from switching to more renewable materials that reduce water and energy use, while also extending the life of the product.

So, if you really want to make a difference, focus on the use and type of fibers you buy.

Try buying low-impact materials like linen and wool, buy from local stores to minimize transportation, and make sure you elongate the life of the products —avoid dry-cleaning or washing them too often, and choose clothing items that transcend fashion trends.

Revisiting the Bloomberg article, we do need to find a solution to the end-of-life of these products, but the impact is rather small compared to everything else. Instead, elongating a product’s life cycle will help more since the one-time impact of each stage will spread over more uses, thus lowering the overall effect.

So, this holiday season, buy local, buy natural fibers (not silk), and buy items that are likely to remain in fashion for longer than FW2022.

Great read. Another way of reducing waste in the industry could be to incentivize producers to produce less. Maybe there's room for technological advancements to predict which clothes should actually get made in the first place