The Secret Sauce of Managing Variety Through Modularity And Commonality in Fast-Casual Dining

A couple of weeks ago, Chipotle launched Adobo Ranch—its first new sauce in five years. At an extra $0.75, it seems like a minor menu tweak. However, this spicy addition represents an experiment in what I like to call the “modularity dividend,” and it reveals why some restaurant chains thrive while others stumble despite their uniformity.

The timing is no accident. Chipotle just posted its first same-store sales decline since the pandemic, with traffic down by 2%. Meanwhile, CAVA—a Mediterranean fast-casual chain often called “the Chipotle of Greek food” (not sure why, to be honest)—is posting an eye-popping sales growth of 10.8%. Sweetgreen, despite its premium positioning and tech-forward image, is hemorrhaging customers with a 6.5% traffic decline.

What explains these divergent fortunes? I think the answer lies not in their ingredients, but in how those ingredients are integrated.

Fast-casual restaurants face a classic trade-off: offering enough variety to attract and retain customers while avoiding the inefficiencies of an overly complex menu. Chipotle’s recent introduction of the new Adobo Ranch dipping sauce underscores this tension.

The burrito chain hopes that tapping into America’s ranch-dressing craze (ranch sales hit $1.3 billion in 2024, surpassing ketchup) will help reverse the same-store sales decline.

But Chipotle’s situation raises key questions: Does variety pay off? And how can chains manage variety modularly—using a few components to generate multiple offerings—to get the benefits of choice without the downsides of complexity?

This is related to our discussion a couple of weeks ago on Rent the Runway.

How do you increase variety and scale without increasing complexity?

In today’s article we take a deep dive into how three prominent fast-casual brands—Chipotle, CAVA, and Sweetgreen—balance variety and modularity. We compare their menu strategies, degree of modular design, and performance outcomes from 2020 to today.

Grab your sauce and let’s dig into the recipe behind modular success.

Variety vs. Modularity: An Operations Perspective

Providing more product variety tends to attract a broader customer base and increase sales—up to a point. Research on the topic finds that initially, expanding variety has a positive impact on sales, but beyond a certain level, additional variety leads to diminishing returns and even lower sales—“too much of a good thing.” In one large-scale study, adding product variety eventually reduced sales once operational performance (like order fulfillment rates) suffered. The lesson is that variety isn’t free: it introduces complexity in supply chains, inventory, and service processes that can undermine both efficiency and customer experience.

To manage this trade-off, companies turn to product modularity and component commonality. By designing a menu or product line around common building blocks, a firm can offer more combinations without proportional complexity. According to research by Song and Zhao (2009) “component commonality has been widely recognized as a key factor in achieving product variety at low cost.” In other words, reusing ingredients or components is crucial to “mass customize” offerings. This approach can mitigate the negative effects of variety on operations by simplifying procurement and preparation, while still allowing combinatorial variety to satisfy diverse customer preferences.

In the fast-casual restaurant context, modularity means using a relatively small set of ingredients across most menu items, enabling mix-and-match customization. The ultimate example is the assembly-line model pioneered by Chipotle: a handful of core ingredients yield thousands of possibilities, and new menu “items” can often be created from existing ingredients. Below, we compare how Chipotle, CAVA, and Sweetgreen embody this modular variety model in different ways, and quantify its impact.

Chipotle: Modular Variety and Cautious Innovation

For most of its history, Chipotle epitomized the “few things, thousands of ways” philosophy. The menu famously consisted of just a few core formats (burrito, bowl, taco, and salad), and almost all items used the same set of ingredients.

This operational simplicity was a strategic choice to simplify food prep, speed up assembly, and cut waste. Despite using only ~20–25 primary ingredients, Chipotle has long touted that customers can customize their meals in tens of thousands of ways. In fact, by selecting different combinations of rice, beans, proteins, salsas, and toppings, one could create an estimated 65,000 unique meals. This huge variety arises from recombining common components, not from an ever-expanding pantry.

This modular approach paid off in efficiency and consistency. Throughout the 2010s, Chipotle’s throughput and unit economics were industry-leading, cultivating a loyal customer base with the promise of “Food with Integrity” and the ability to “have it your way”—without a cluttered menu. Notably, Chipotle avoided the frequent menu-item additions that fast-food rivals would use to spur short-term sales. Instead, growth came from new stores and steady customer traffic drawn by the customizable experience. This model allowed Chipotle to combine fast service and high quality, winning over health-conscious consumers and achieving an average spend nearly 3X that of typical fast food. In-store, the assembly-line serving system and cross-trained staff further leveraged the limited ingredient set to maximize speed.

However, a complete lack of new flavors can eventually make a menu feel stale. By the late 2010s, competition and consumer demand for novelty pushed Chipotle to carefully expand its offerings. CEO Brian Niccol (who joined in 2018 from Taco Bell and recently left to lead Starbucks) began testing new items, but he was acutely aware of the operational risk. “The restaurant [was] known for a purposeful limited menu… the assembly line isn’t set up for variety,” Niccol noted, warning that a poorly integrated item (like a hand-mixed quesadilla or a milkshake) could “slow you down” at the line. The solution was to introduce variety through the same modular system, so as not to “break” the operation. For example, Chipotle rolled out quesadillas as a digital-only item (made at a separate station), to avoid bogging down the main line. Likewise, rather than adding completely novel ingredients, Chipotle largely innovated by recombining or seasoning existing components.

This strategy is evident in Chipotle’s recent launches. In 2023, it added quesadillas with grilled fajita veggies—officially adopting a viral TikTok hack. Because it used existing ingredients, the new item nearly doubled quesadilla sales without adding complexity. Similarly, the Chicken Al Pastor (2023) and Honey Chipotle Chicken (2025) creatively repurposed the existing chicken with new marinades, driving significant sales boosts. These modular innovations helped Chipotle manage a tougher economic climate, including its first same-store sales decline (-0.4%) in Q1 2025. Responding with targeted innovation—like the recent Adobo Ranch dip, which pairs easily with existing items—Chipotle continues using modularity to attract customers without operational disruption.

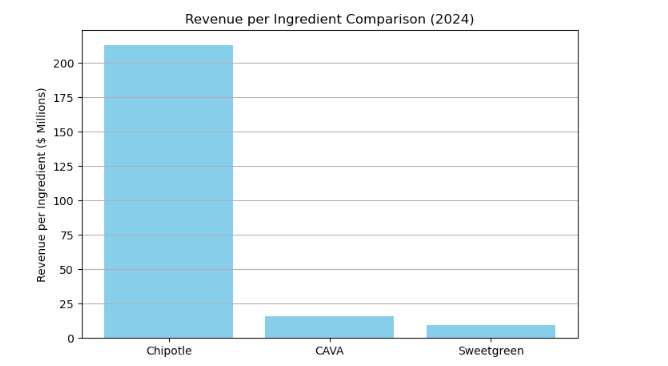

Chipotle’s modular menu approach significantly enhances its efficiency. As illustrated by the revenue per ingredient comparison (2024), Chipotle dramatically outperforms competitors CAVA and Sweetgreen, generating more than $200 million in revenue per ingredient. This highlights how effective modular innovations—repurposing existing ingredients for new menu items—translate into exceptional economic leverage, making Chipotle’s operational discipline a critical competitive advantage

Using the latest filings, Chipotle achieved an overall operating margin of 17.8% in 2024, with a restaurant-level margin of 26.7%. In Q1 2025, margins held up at 17.2% overall and 26.2% at the restaurant level.

Chipotle shows that variety pays off if managed thoughtfully. Each new addition is assessed for both customer appeal and operational fit. Previous attempts at adding complex items, like the initial queso launch in 2017, struggled. However, the recent modular innovations succeeded by sticking closely to Chipotle’s formula. This strategy mirrors trends at chains like McDonald’s and Taco Bell. By leveraging 50-60 ingredients into thousands of menu combinations, Chipotle achieves exceptional operational efficiency, helping it grow into a $70 billion brand. Still, it must continuously refresh its approach creatively and carefully introduce new elements to avoid menu fatigue.

CAVA: Embracing High Variety via Common Components

In contrast to Chipotle’s historically relatively spartan menu, CAVA has, from the start, offered a broader palette of ingredients—yet it, too, thrives on a modular, build-your-own format. CAVA is a fast-casual Mediterranean chain (over 260 locations after its 2023 IPO) known for customizable bowls and pitas loaded with Middle Eastern/Mediterranean flavors. Customers choose a base (greens or grains), add dips/spreads, a protein, and choose from a large number of toppings and dressings.

The numbers are staggering: by the company’s estimate, CAVA’s menu supports “17 billion possible combinations” of a bowl or pita (...yes, billion with a “b”—far outpacing Chipotle’s 65,000). This combinatorial explosion comes from allowing multiple choices in each category—e.g., you can pick up to 3 different dips (hummus, tzatziki, roasted eggplant, etc.), any assortment of ~13 toppings (like feta, olives, pickled onions, cabbage slaw, crispy pita chips, etc.), and several dressings. In essence, CAVA invites the guest to “mix and match everything.” The variety is extremely high, but it is consciously engineered through a modular set of components prepared in-store daily. Furthermore, CAVA can frequently introduce fresh, seasonal offerings without complicating kitchen operations or the supply chain.

CAVA’s rapid expansion (50–60 new units per year) and impressive 2024 sales growth (13.4% same-store sales, nearly 9% traffic increase, and Q4 comps up 21%) demonstrate that this strategy clearly pays off. With average unit volumes at $2.9 million—close to Chipotle—CAVA attracts customers seeking variety and freshness, driving repeat visits. Its strong digital presence (over one-third of sales) further boosts engagement by promoting customization.

The figure below quantitatively illustrates CAVA’s impressive same-store sales growth in 2024, highlighting the effectiveness of its expansive yet modular variety strategy.

CAVA’s extensive variety relies heavily on strong operations, including centralized production and in-store assembly. Acquiring and converting Zoe’s Kitchen locations helped the firm scale efficiently. CAVA’s disciplined execution allowed them to expand to hundreds of outlets and achieve profitability in 2024, demonstrating that extensive variety can succeed commercially when backed by modular processes and ingredient commonality.

In numerical terms, CAVA has higher absolute complexity than Chipotle (dozens of ingredients vs. ~20), but it also delivers astronomically higher variety. Its variety-to-component ratio is arguably even greater, on the order of billions of combinations from perhaps a few dozen ingredients. Each additional ingredient introduced—a new seasonal dressing or topping—multiplies menu possibilities exponentially. As long as those ingredients remain modular—widely usable across various orders—the marginal cost remains low while the marginal consumer benefit can become significant.

Sweetgreen: Seasonal Innovation and the Cost of Complexity

Sweetgreen, a salad and grain bowl fast-casual concept, provides a third perspective on managing variety. Sweetgreen built its brand on seasonal, healthful, customizable salads, often incorporating local produce and trendy ingredients. Compared to Chipotle and CAVA, Sweetgreen’s menu has been more fluid and experimental—new salads, warm bowls, and sides regularly rotate—and the chain has embraced significantly more ingredient turnover with the seasons. This strategy has strengths in driving frequency (loyal customers get excited to try the latest bowl) but also brings operational challenges.

In 2021–2022, Sweetgreen leaned heavily into menu expansion. They introduced warm protein plates, new dressings, and even sides like air-fried “sweetgreen fries.” The variety was meant to attract dinner customers and new demographics (e.g., a Steakhouse Bowl to lure in more male consumers, or hot plates to compete with casual dining). However, by 2023 the company realized it had perhaps stretched its operations too thin. Sweetgreen’s leadership noted they “took a break” from frequent seasonal launches in 2024 to focus on operational consistency after so much newness. They had reduced their typical seasonal menu changes from five per year to just two in 2024. This pause was partly to integrate big changes (like the new automated “Infinite Kitchen” system in some stores) and to ensure the core menu (like the new protein plates) could be executed flawlessly. In effect, Sweetgreen learned that introducing variety has an operational cost, and doing “too much, too fast” can hurt throughput and service. CEO Jonathan Neman admitted, “introducing all those new things would have been challenging [operationally]” without first building better systems.

Yet, Sweetgreen also learned the downside of offering too little variety. In mid-2025, Neman reflected that the hiatus from seasonal innovation had a negative impact: “We lost some of our core customers… due to a lack of innovation from the seasonal menu perspective.” Regulars who were used to seasonal salads coming and going missed that excitement. Additionally, data showed those seasonal LTOs were “incredible drivers” of retention and transaction frequency. In essence, Sweetgreen’s customers crave novelty (within the context of healthy bowls), and not delivering it hurts the brand’s value proposition. Armed with this insight, Sweetgreen declared that 2025 would mark a return to frequent seasonal menu changes—about six per year—but with improved operational readiness. Neman emphasized they “built the system and capability” to handle this cadence, expressing confidence in “bringing newness to the menu at least six times a year” going forward.

So, how is Sweetgreen managing variety in a modular way? A few aspects stand out:

Base Ingredient Reuse: Sweetgreen’s core ingredients (greens like kale, romaine; grains like wild rice and quinoa; proteins like chicken, tofu, etc.) form the backbone of both their signature bowls and DIY options. New salads typically repurpose these bases with just 1–2 new elements for flavor. For example, a seasonal Korean BBQ Bowl introduced in 2025 featured KBBQ steak and unique sauces, but still sat on familiar romaine and rice, with common add-ins like pickled cabbage and spicy broccoli (which were themselves adaptations of existing pickling and roasting techniques). By anchoring new items in many existing components, Sweetgreen limits the incremental complexity to a few dressings or one protein.

Time-Limited Ingredients: When Sweetgreen does add exotic ingredients (e.g., persimmon in a fall salad or miso-glazed salmon as a summer protein), it often does so as a seasonal special, available for a limited window. This creates perceived variety but doesn’t permanently expand the inventory—the new ingredient is phased out after the season. Essentially, Sweetgreen staggers variety over the calendar, which is a form of temporal modularity. Stores only handle that extra ingredient for a few weeks, mitigating long-term complexity.

Operational Streamlining: Sweetgreen’s recent earnings calls highlight a focus on “reducing operational complexity… to enable culinary innovation.” The company reported efforts to simplify prep processes—for instance, pre-destemming kale and optimizing how broccoli is prepped and roasted—to save labor and “free up” capacity for doing new menu items well. By “reducing back-of-house complexity,” they can redeploy staff to maintain speed even as the menu changes. This is a direct acknowledgment that to sustainably offer variety, you must invest in efficiency elsewhere. Sweetgreen even introduced automated makelines (Infinite Kitchen) in some stores to handle customization faster, again to make a broad menu feasible at scale.

Finding the Optimal Variety: Does Modular Variety Pay Off?

Analyzing Chipotle, CAVA, and Sweetgreen, a central insight emerges clearly: variety can significantly enhance competitive advantage and growth when managed through a modular design approach. Despite their differing degrees of menu complexity, all three chains strategically rely on common ingredients to streamline kitchen operations. This practice helps them sidestep or significantly reduce the operational complexity typically associated with broad menu variety.

But there are differences among them that are worth noting.

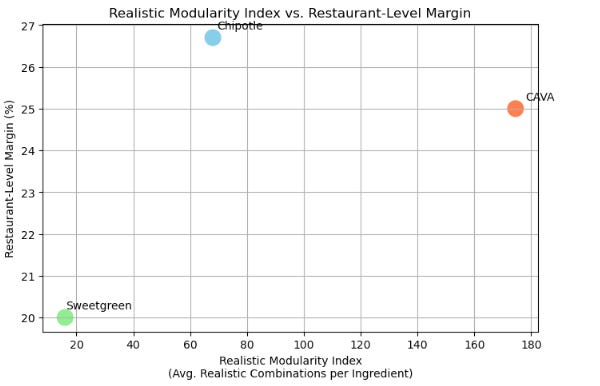

Realistic Modularity and Financial Implications: Examining practical modularity through realistic ordering combinations further clarifies each chain’s strategy. Chipotle, with approximately 22 ingredients, achieves about 1,500 practical combinations, resulting in a strong modularity index (~68). CAVA, using roughly 43 ingredients and extensive cold-prep modularity, offers between 5,000 and 10,000 combinations, significantly boosting its modularity index (116–233). Conversely, Sweetgreen, despite a similar ingredient count (~40), offers only about 500–800 practical combinations, yielding a modest modularity index (12–20).

These outcomes underline modularity's critical importance. Chipotle sustained robust margins and line efficiency by strictly limiting new SKUs and procedures. Early attempts at more complex offerings (2018) demonstrated clear operational slowdowns, prompting a quick return to modular simplicity. CAVA, benefiting from high-volume sales and common ingredient prep efficiencies, consistently achieved strong restaurant-level margins. Sweetgreen initially faced challenges from operational complexity but rebounded after simplifying prep processes (such as pre-cutting ingredients) and increasing automation, eventually reaching margins around 20% by 2024. The accompanying graphs vividly illustrate these operational efficiencies: Chipotle and CAVA both demonstrate higher margins strongly correlated with their modularity indexes, while Sweetgreen’s lower margin correlates with lower practical modularity.

Yet, there is a crucial balance: too little variety risks customer fatigue, while excessive or poorly managed variety damages throughput, margins, and even sales. Sweetgreen's experience illustrates the importance of carefully calibrated menu complexity, evidenced by their shift to controlled, seasonal variety coupled with enhanced training and technology. Meanwhile, Chipotle demonstrates the advantage of incremental innovation, adding modular extensions (such as sauces and marinades) that maintain common ingredient use. Both Chipotle’s social media-driven "menu hacks" and CAVA’s user-generated bowl competitions effectively enhance perceived variety without adding operational complexity.

Final Thoughts

Effectively managing variety in food service is ultimately about scaling strategically without losing operational control. Firms that master the art of generating many SKUs from a few core items enjoy dual benefits: robust sales growth from variety and cost efficiency from simplicity.

Chipotle’s disciplined modular extensions have ignited growth without compromising operational speed; CAVA’s shared component approach has enabled massive scalability alongside customer excitement. These successes clearly demonstrate that the path to sustainable growth lies in balancing variety and operational simplicity.

But a final word of caution.

Too much modularity, and your burrito becomes IKEA furniture. customers forced into tedious assembly, complexity disguised as simplicity, and missing ingredients causing frustration instead of satisfaction.

Balance is key: modularity should simplify choice, not outsource complexity.