The Supply Chain and the Fed

Last week, the Federal Reserve approved the “first interest rate hike in more than three years,” hinting that many more are to come.

I am not a finance guy or a macroeconomist (and you’re not here for either), but I am sure you are curious about the implications for our already fragile and embattled supply chains, what the impact is on us, and which products we might be running out of next.

But first, you may be wondering why or how interest rates impact the supply chain.

And that would be a very legitimate question.

Well, it has to do with the notion of inventory holding cost. Let’s assume that a firm could earn 10% on money deposited in the bank (I know it’s hypothetical, but bear with me). Let’s also assume that the firm (which buys/manufactures and sells) has an item worth $100 on the store’s shelf for a year (again, bear with me). Even if that item is sold, the firm will have lost $10, which is the amount it could have earned if that money had been in the bank rather than on the shelf.

This is clearly an oversimplification, but just to give you an idea, a few years ago, Bloomberg wrote about the $16.2B worth of inventory Boeing had for its 787 Dreamliner. For a firm that had a weighted average cost of capital of 10% (pretty common at the time), that meant $1.62B in opportunity cost (i.e., money that could have been invested in alternative projects).

When computing a product’s TLC (total landed cost), one must account for all costs, from raw materials and logistics, to shipping and warehousing, but also the opportunity cost of inventory. For very long supply chains with a lot of inventory along the way, this opportunity cost can be quite significant, and is basically the cost of carrying inventory.

In fact, over the years, the physical costs associated with carrying inventory have decreased due to automation and increased efficiency, while the financial costs of carrying inventory have become more prominent.

The Impact on Supply Chain Decisions

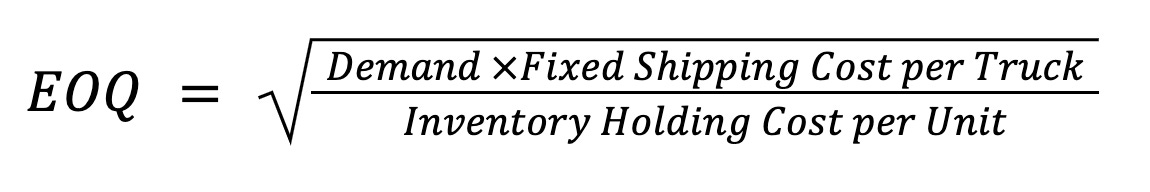

The most basic supply chain model is the Economic Order Quantity, or simply EOQ.

The question this model tries to answer is what quantity should a supply chain manager order when faced with a fixed cost incurred every time they place an order (e.g., shipping cost, which is incurred based on the number of shipments, rather than the number of units shipped).

If the firm wants to maximize the economies of scale by spreading the costs of shipping over more units, they should order a full truckload. The issue is then they have to carry a significant amount of inventory, which can be quite costly as we just discussed. If the firm wants to minimize the cost of holding inventory, it should just order one unit at a time, or order based on what the demand was over the last week or day (but that will be a very inefficient use of the transportation options it has).

To balance these two costs, one can show that the optimal ordering quantity is:

The first thing to note here is that as the shipping costs increase, firms will try to secure more inventory. And indeed, we have seen this over the last few months, although it was also driven by the fact that firms were already experiencing significant shortages.

But I would like to go back to the initial purpose of this post: the impact of interest rates.

In terms of supply chains, interest rates impact the per-unit holding cost. If firms follow this equation (or the logic behind this equation), as interest rates increase, so will the holding cost per unit. And as the holding costs increase, firms will order less, to reduce their inventory.

Let’s try to see whether this prediction holds historically:

2002-2008

During this period, which came after the dot-com bubble, and after a few years of low interest rates, the latter started to climb rapidly, and showed only a slight decrease just before the global financial crisis in 2008.

Since the amount of total inventory is a little misleading, because the economy is expanding at the same time, we will look at the inventory-to-sales ratio, which is more accurate as it measures time. Specifically, the average time inventory sits on the shelf or the warehouse.

As you can see below, the general trend is a decrease in this metric. In other words, as interest rates increased, firms carried relatively less inventory. Firms were forced to become more efficient since they couldn’t be negligent with their money.

We can also observe that while changes in interest rates are pretty smooth, the same does not apply to inventory. The financial world is neat. Supply chains are messy.

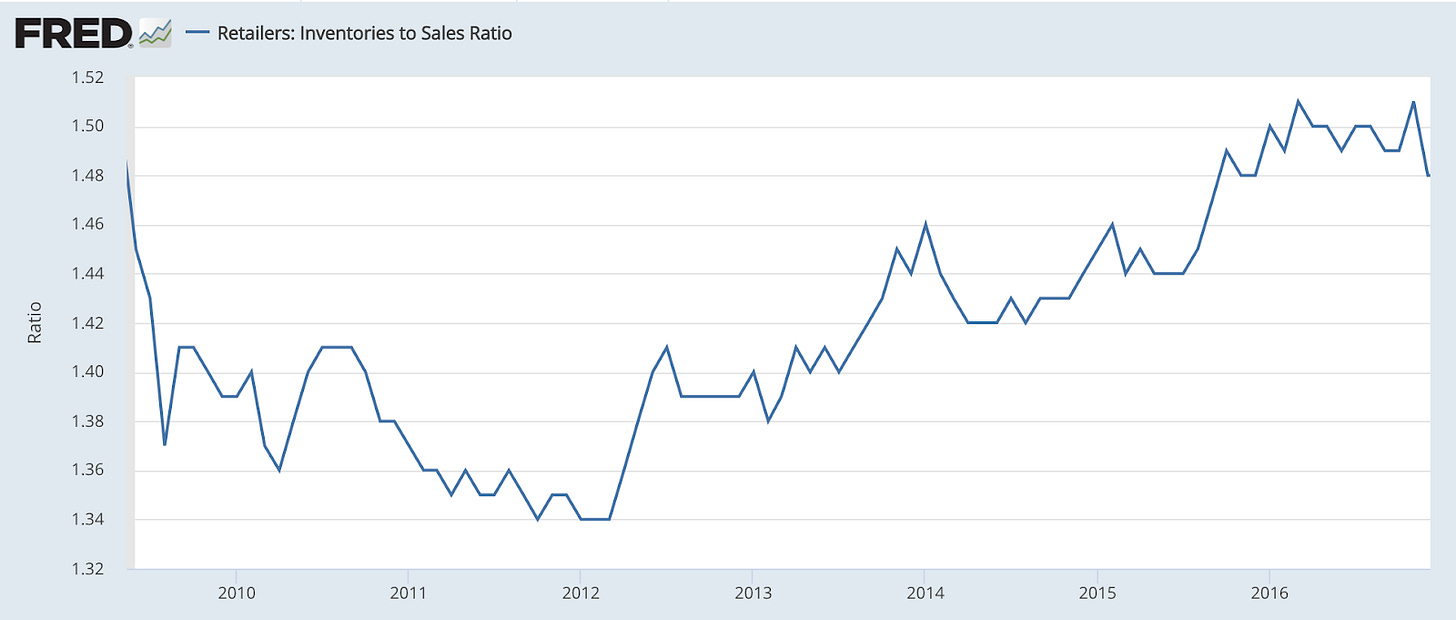

2008-2016

After the financial crisis in 2008, interest rates remained very low for a long, long time.

And indeed inventory increased.

The main thing to notice here, apart from the trend, is the time lag. Inventory began climbing only a little after 2012 because it took some time for people and businesses to recover from the recession. Since supply chains involve people and physical products, they tend to have a slower response time.

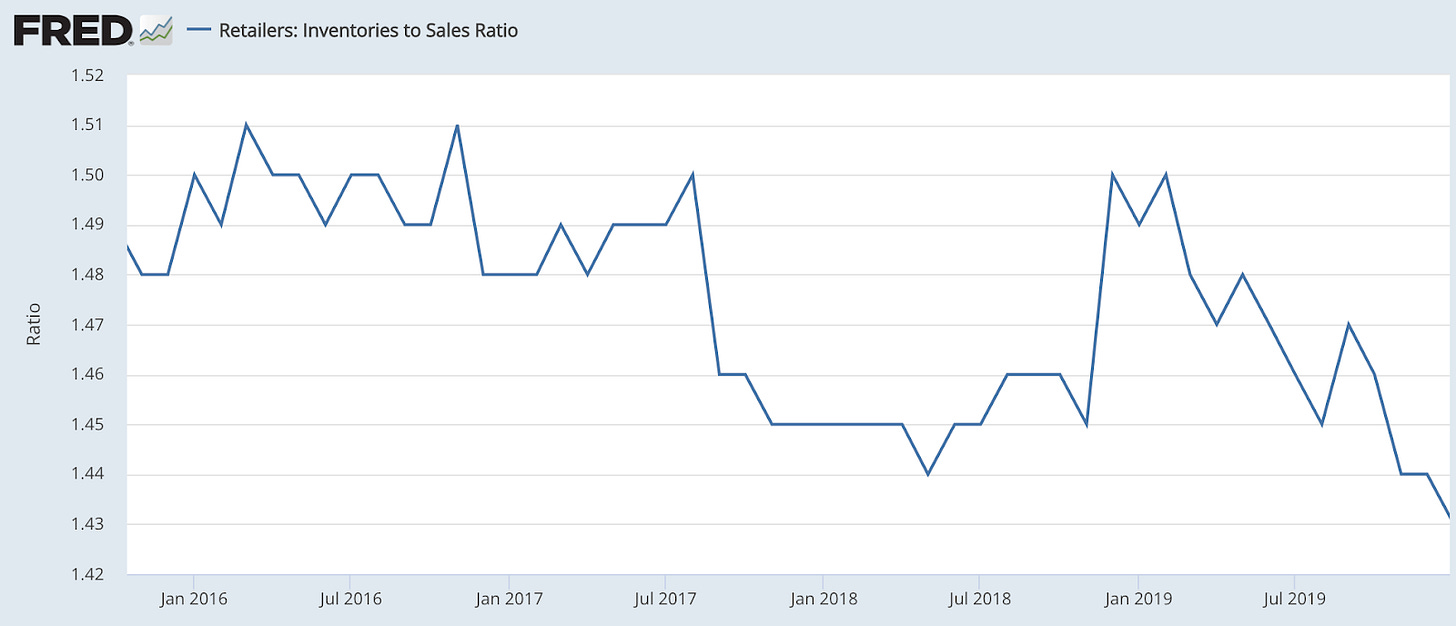

2016-2019

During this period, interest rates started to increase again steadily.

And, no surprise, firms started reducing the amount of inventory they carried.

Again, lots of rough edges, but the overall trend is clear.

What Does it Mean for Us?

Back to the present. So what does this all mean for our current situation? Will we pay more for products (beyond the already soaring inflation)? Should we expect more shortages?

I think the answer is more complex than it seems.

Will we see More Shortages?

I expect the overall service levels of firms to remain somewhat the same. Both the cost of overstocking (which is driven by the holding cost and cost of materials) and the cost of understocking (which is driven by the firm’s profit margins) are expected to increase, resulting in probably a somewhat similar target service level.

But since firms will carry less inventory (a little less), we should expect more stockouts.

Will Costs Increase?

Firms are expected to carry less inventory, but the inventory cost per unit is going to rise.

Based on the EOQ formula, which clearly doesn’t tell the whole story, firms are expected to carry less inventory, but the change will be by a factor of square root. So overall, firms will carry a little less inventory, but that inventory will be more expensive.

If inventory costs increase, the TLC of the product will increase, and who is going to pay for this increase? Did I mention inflation already?

But if we’ve learnt anything from the historical tour we took here, these changes will be somewhat lagged and not as clear as their financial counterparts.

We will pay more, and we will probably have more stockouts. But we are already used to this, and as long as the situation remains gradual, it will take a while until we really feel the impact…at which point it will already be too late to react.

Just like a boiling frog.