Back in 2019, in a popular article, the Economist had predicted that Uber will never be profitable. The article “Can Uber ever make money?” outlined the main challenges:

“The trouble is, as competition increases, ride-hailing becomes a commodity business. Customers care little whether they ride with Uber or Lyft, as long as it gets them from a to b. That means neither firm can easily increase profits by raising fares, but may instead have to offer discounts. Likewise, the ride-hailing firms do not own their cars: their drivers do, and so have no reason to be loyal. That forces the firms to pile on incentives to stop drivers from deserting, kicking profits even further down the road.”

And the final answer is clear:

“Uber will surely have a place in the future of transport. It may be able to increase rider and driver loyalty by replacing fares with monthly subscriptions. It may settle for dominating some cities, leaving others to rivals, provided that does not violate antitrust rules. History suggests that profits will be hard to come by. But at least its name should live on.”

Well, five years later, Uber is profitable:

This was a surprise for many. The firm spent heavily on growth and, together with Wework, was known as the poster boy of the strategy “growth for the sake of growth.” But things changed, and the firm has become more moderate in its spending and in how it manages its operations.

In today’s article I aim to uncover the factors behind the firm’s profitability. We’ll explore whether this success is solely attributable to economies of scale or if there’s a deeper element, such as a pivotal decision, that truly enabled the company to achieve a breakthrough. Additionally, we will question the durability of this profitability and whether we can expect an expansion in their margins moving forward.

Uber Economics

Uber economics are quite simple:

From the amount received from the customer, Uber must pay taxes and tolls, the driver (both their earnings from the particular ride and other incentives), and other costs.

In the following graph and just before their IPO, Lyft shows a positive gross profit. However, once we account for the cost of R&D (developing and maintaining the app as well as all the tools that allow the marketplace to scale) and other costs related to sales, marketing, and management, it seems that both Uber and Lyft have been losing money for several years:

While many of the costs to the left of the Gross Profit increase (or decrease) depending on Bookings (the amount paid by the customer) and don’t change as the number of rides increase, the costs to the right, if managed appropriately, should not increase with volume or bookings and, thus, should decrease per ride (or per $ of revenue).

And indeed, in 2022:

“Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi vowed to rein in costs at the ride-hailing company in the face of a “seismic shift” in the financial market, according to a memo sent to employees that was first reported by CNBC. The effort to reduce spending is in response to the dramatic upheaval in the labor market that has Uber scrambling to find drivers to meet growing demand. Khosrowshahi said that, moving forward, the company will treat corporate hiring as a “privilege,” suggesting that Uber may be looking to freeze or even reduce its staff numbers as it aims to become a leaner operation.”

And not long after, the firm turned its first profitable quarter. This is simple “supply-side economies of scale”: the firm amortizes its “fixed costs” (such as R&D and G&A) over more rides, so as volume increases, it starts making money.

However, it’s clearly not as trivial as it sounds. When firms prioritize growth, they have less time to invest in efficient operations that drive economies of scale.

For example, until not so long ago, Uber employed 50 GMs, each managing operations in different U.S. cities. This was an essential part of Uber’s growth playbook. These GMs had a team (and a big budget) and made decisions at the city level. The mandate was clear: growth. The firm’s current strategy involves one GM managing the entire U.S., and most decisions are centralized. This means significantly higher efficiency paired with the ability to drive costs down.

All this shouldn’t be surprising, but the claim is that it’s not enough: To truly drive profitability, Uber must do more.

Uber’s Demand Side Economies of Scale

One of the central claims that emerged after this surprising financial outcome was that Uber’s path to profitability required them to pay their drivers less.

Uber is a marketplace —it offers a service and charges a fee for that service (customers are charged a certain fare for the ride). Uber takes a cut part of which they keep for themselves (and we’ll refer to as take-rate), and part of which they use to pay drivers.

In the article I cited above, Uber claims that nothing has changed in how they pay their drivers.

Luckily for you, I’m working with Daniel Chen (who will be joining Boston College in the Fall) and Ken Moon on a paper studying related topics. The paper is still a work-in-progress and will be ready in a couple of weeks (right Daniel?), but we can share some preliminary results (just to be clear, the two of them take all the credit; I’m merely there to cheer them on).

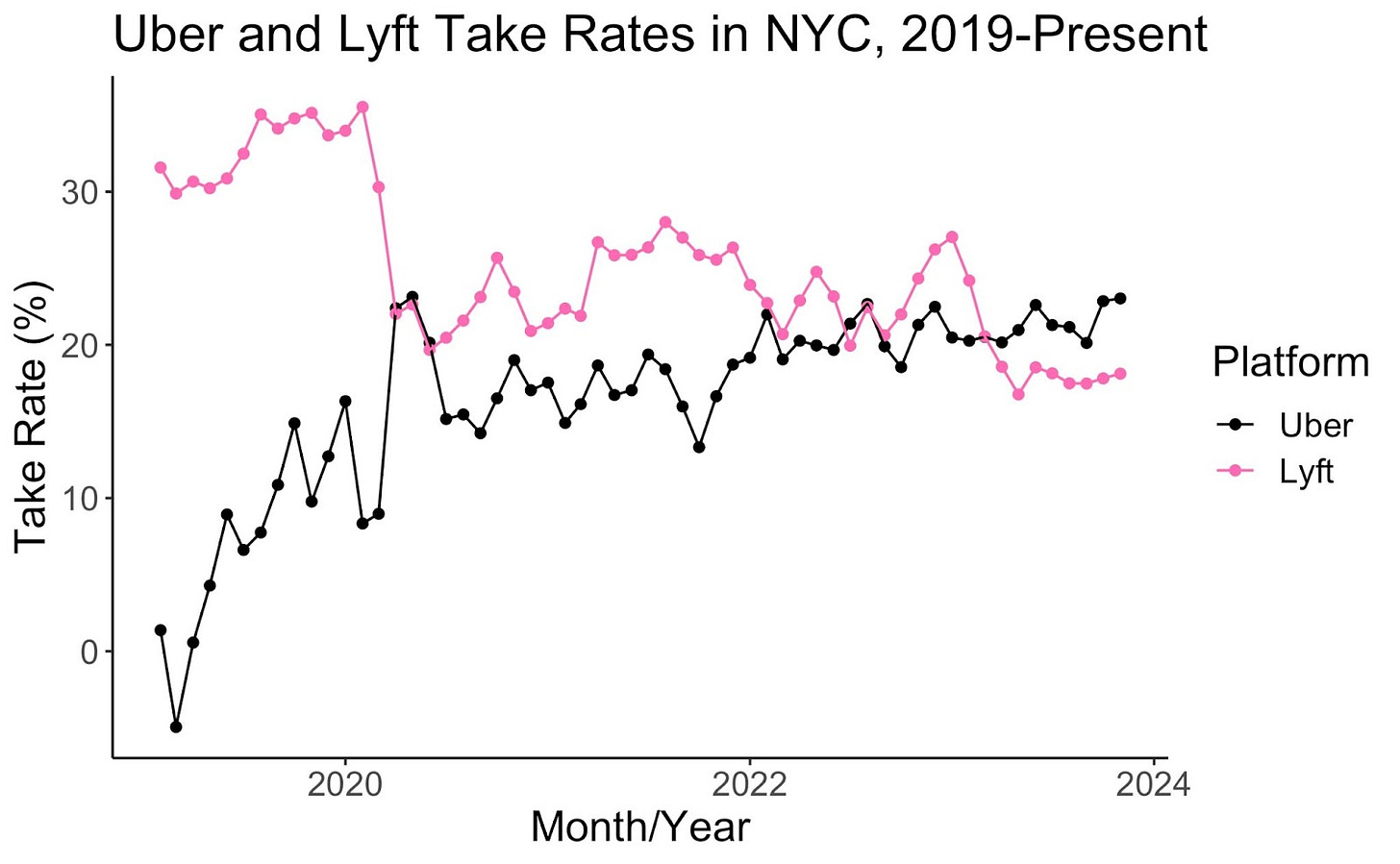

So let’s start by looking at how the take-rate has changed since 2019 in NYC. Our data reveals the payments received by drivers and the payments made by customers, allowing us to compute Uber’s share (take-rate):

As evident, Uber’s take-rate has increased significantly while Lyft’s has decreased —their share has not changed much leading to 2024, at least not in NYC. A Forbes article shows the results across the entire Uber-verse:

The main change the article points out as facilitating this increase, is the 2022 implementation of “upfront pay.”

Uber’s upfront fares plus destination (UFD) policy, which rolled out in the U.S., changes how drivers are paid by using an AI algorithm to set fixed earnings per trip, moving away from traditional time and distance calculations. This system offers drivers pre-trip details like destination, estimated time, distance, and final pay.

Despite the benefits, drivers face challenges with the algorithm-based system. They are often forced to make quick decisions regarding trip-offers under the threat of being sidelined or placed in a “penalty box” for declining too many rides. Furthermore, a bidding mechanism called “Trip Radar” forces drivers to compete for trips, often leading to accepting lower-paid rides, which intensifies competition and potentially leads to reduced earnings for everyone.

At least in NYC, the data show that the trend of increasing take-rates seems to last longer than just 2022. NYC is also a more competitive market than any other Uber market (we’ll come back to this).

I refer to the phenomenon of increasing the take-rate as the firm grows, as demand-side economies of scale or network effects. A marketplace has both same-side and cross-side network effects.

As more drivers sign up to the platform, the value for the customers increases (less wait-times, less surge pricing). And as more customers use the platform, the value for the drivers increases (less idle time, possible surge pricing - higher earnings). Of course, one has to account for the same-side network effects, but as long as the platform is growng, they should be dominated by the cross-side network effects.

The take-rate is the way the platform monetizes these network effects.

I refer to it as demand-side economies of scale since they increase the willingness to pay on both sides, reduce churn, and decrease the need to use incentives as the marketplace scales.

The term “demand” may be confusing, but I’m using it to distinguish between the supply (internal costs) and the network effect (value to stakeholders in the ecosystem).

So why is the firm claiming that their take-rate has remained unchanged?

“Over nearly a decade of losses, many observers suggested Uber would never be profitable. Now that we are, those same skeptics assert that Uber’s financial improvement must have come at drivers’ expense: in other words, the only reason Uber was able to become profitable was by raising prices while taking an ever larger share of the pie.

This is false.”

The Uber Polciy article goes into great length and wordsmanship to say that the graphs you see above are not the graphs you see above.

The Drivers’ Side of Profitability

So why isn’t Uber celebrating these network effects? This is what they had promised their investors all along, in this David Saks napkin explanation of Uber economics:

While Uber is willing to acknowledge that customers are paying more than before, they’re unwilling to admit that the increase in drivers’ pay is more moderate. And just to be clear: Uber isn’t paying less than Lyft. Actually, they’re paying more.

So why refuse something that is clearly true based on the data?

I think part of it is because Uber doesn’t want to be considered a monopoly (which just to be clear, it’s not). Nevertheless, having the ability to extract a significantly larger piece of the pie possibly means they have disproportionate market power compared to other players. The following graph shows how Uber has consistently held a significant part of the market share:

One way to see how Uber exercises this market power is to look at the ability of drivers to multihome: be on multiple platforms and switch between them.

I would claim that as customers, we have many transportation options, including those outside the gig economy. When I’m in NYC, I’ll use Uber if the subway doesn’t serve my destination, and Taxis if Uber is too expensive or too slow. I must admit, I rarely use Lyft.

But an Uber driver has fewer options. They can switch to Lyft, or DoorDash or Amazon Prime, but that’s it. And not all options are available in most cities or very lucrative at any hour of the day. Many drivers don’t multihome. In fact, our data in NYC shows that 40% never multihome. Why? We don’t know.

Among those who multihome, there’s a wide spectrum of behaviors, with some being more strategic and some less. Being strategic means declining more offers and waiting for a better ride, or spending more time searching.

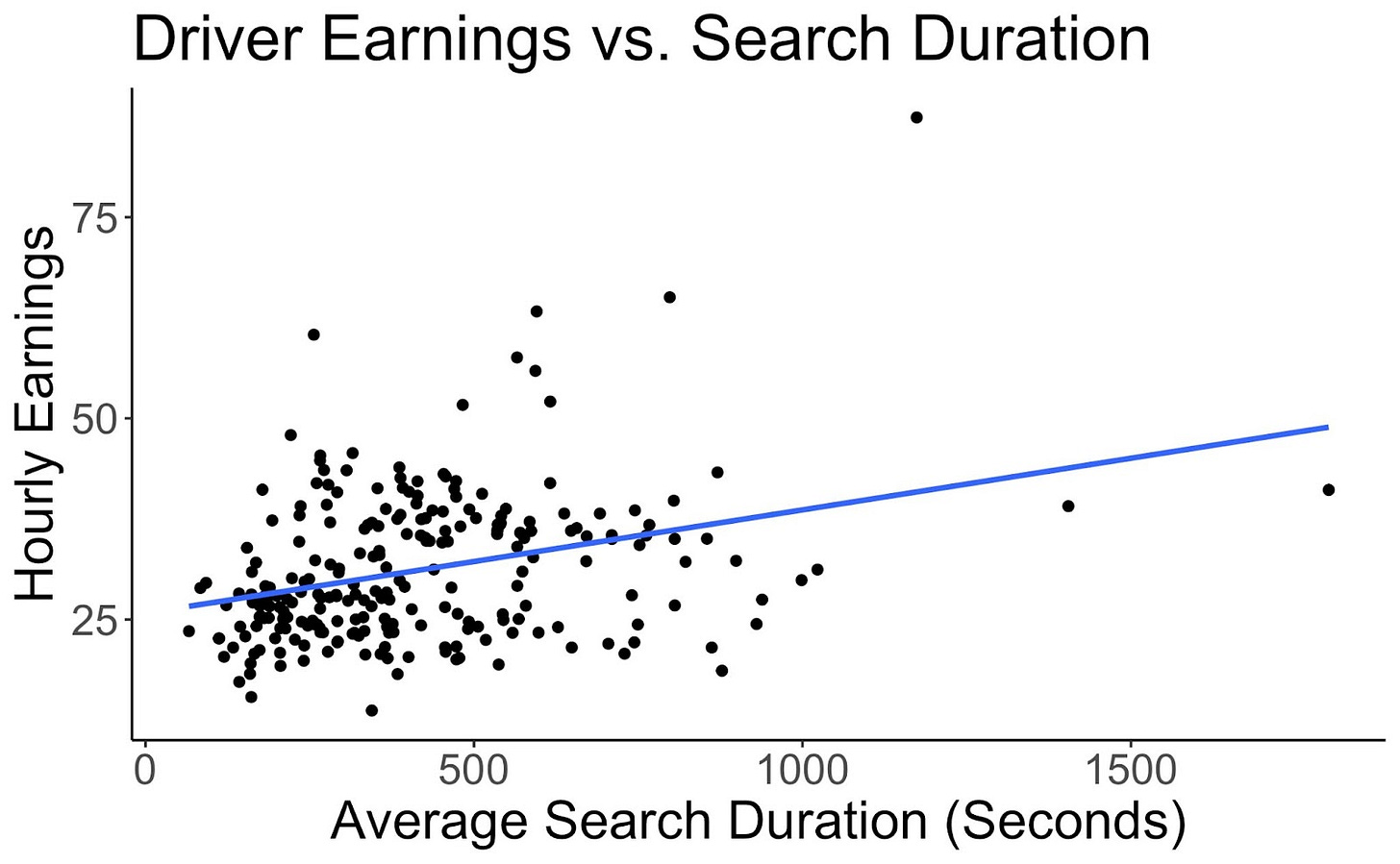

If you’re wondering whether being strategic is beneficial to the driver, the answer is quite conclusively yes! The graph below shows how earnings per hour change as drivers spend more time searching (in our data, we observe how drivers behave once rides are completed):

As evident, drivers who spend more time searching earn more.

But you, the careful econometrician, might say: maybe these drivers just know where to be.

So for you, the careful reader, we dug deeper.

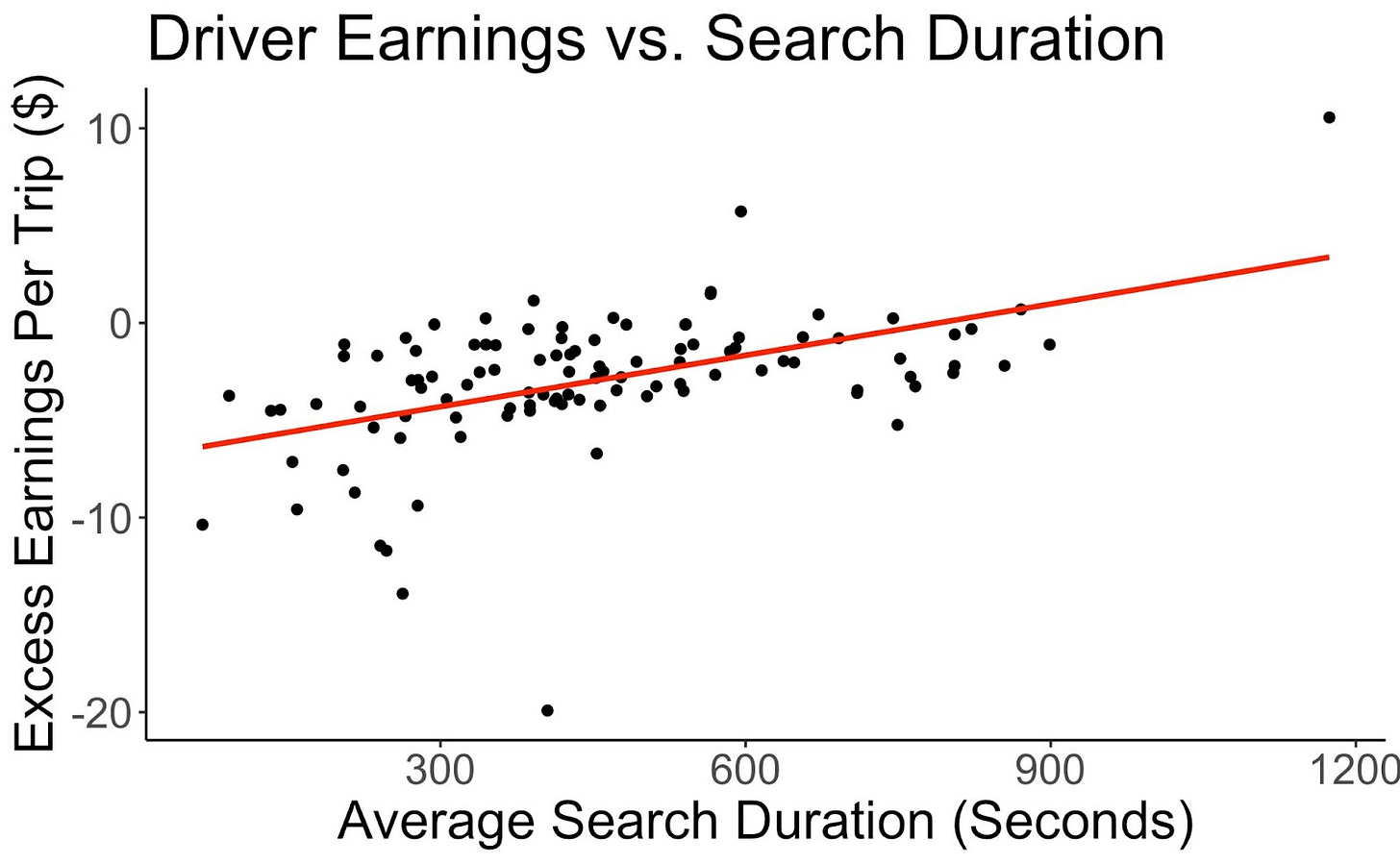

We show that this is not the case: their excess earnings (earning above the average trip going out from where they were) is actually higher. Those who spend more time searching get better trips.

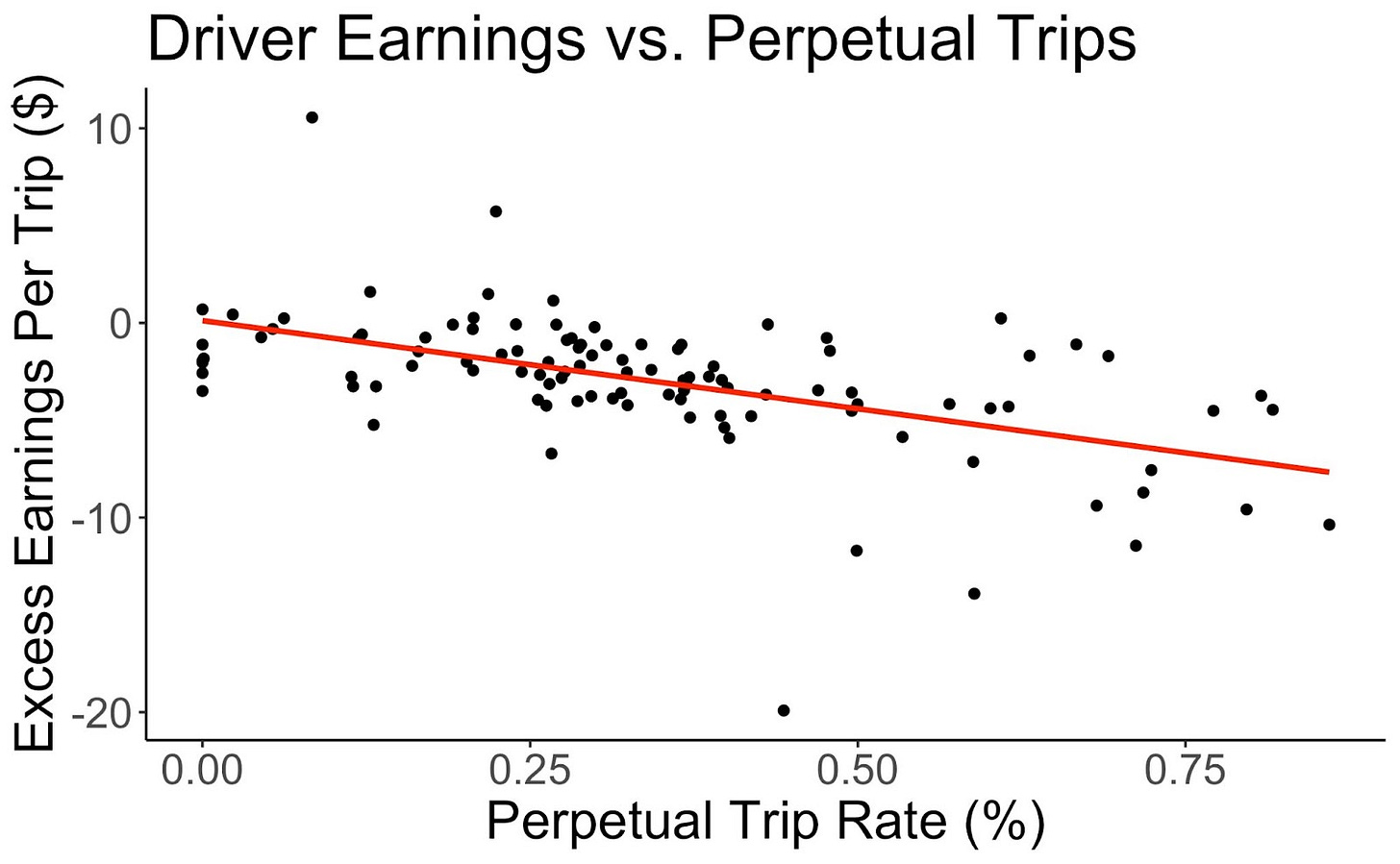

Even more so, those who settle for the offer Uber gives them while driving are worse off.

We call these “perpetual trips.” You’ve probably been on an Uber ride where the driver receives an alert on the Uber app notifying them that there’s a trip starting very close to your destination, promising them the ride so they won’t wait or search for another ride.

The result is very conclusive here as well: the drivers that tend to accept more of these offers, make less money, and have lower “excess earnings.” They get the worst available trips in the area.

And this is the data Uber doesn’t want us to see.

This is also the data they don’t want regulators to see.

Drivers that stick with Uber are absolutely penalized for doing so.

This is the type of market power that Uber doesn’t want us to know they have.

(and I will stop typing one sentence per line for emphasis…)

And this is in NYC where drivers have many options. You can imagine how things are in other cities where options are limited.

As I mentioned, the paper is still a work-in-progress, so additional analysis is conducted, but the results are very robust. And just to be clear: I’m not being paid by anyone to publish these results, and I have no financial incentives whatsoever.

Bottom Line

The revelation that Uber can significantly maximize profits from its drivers highlights a critical aspect of the gig economy. It underscores Uber’s ability to achieve what regulators have long feared: treating drivers as de facto employees without offering them the corresponding benefits. This situation points to a highly unstable and precarious work environment.

While Uber appears profitable, the stability of their profits is questionable, particularly as regulatory scrutiny could compel the company to formally employ many, if not most, of their drivers. Despite their current financial success, Uber aims to maintain a low profile, as their margins are narrow and more vulnerable to regulatory changes than to market competition.

This is fantastic. Could you go into more detail about why a tighter labor market hasn’t overwhelmed Uber’s ability to increase its take rate? If I understand your analysis correctly, it appears that Uber has increased take rate by effectively gamifying the driver ride selection experience. This feels similar to your piece on variable pricing. Drivers value ride certainty and Uber can exploit this by offering lower pay to drivers who elect to always have the next ride booked.

It’s just surprising to me that they’ve been able to outpace competition from other industries for drivers as unemployment decreased. I had expected a tight later market to be a massive challenge for ride-sharing companies. Obviously this interacts with the supply of Uber drivers in the market. Has Uber also become better at targeting supply to use cases where it can be profitable?

If Uber has used its technology to improve how it optimizes the mind-bogglingly complex problem of balancing demand, supply, driver pay structure, and and market pricing, that would auger well for the “Silicon Valley-ization” of more old school industries over time. Do you agree or disagree? What would differentiate Uber from something like Flexport, which has struggled? Is there simply a constrain on the availability of computer science talent and a minimum scale needed to achieve these kinds of results?

My personal experience, which may or may not extrapolate, is that I select Uber/Lyft versus Taxi based on use case. I live in the Chicago suburbs. For airport trips, the suburban taxi service is both more reliable and less expensive, so I’ve switched. But for ad hoc rides around town, into/from Chicago, etc., I don’t even think of taking a taxi and start with a ride-share app.

Gad, I really enjoyed your insightful article on Uber's improving economics.

Globally, Uber reported a 30% YOY increase in drivers on their platform in 2023, and a 15% increase in engagement (ie, online hours per driver). That’s a 43% increase in supply, far outstripping (~3X) their growth in trip demand. The inevitable consequence of this driver oversupply has been: 1) enabling Uber to substantially cut driver pay per trip (11.9% in the US, as I reported in December); and 2) providing fewer trips per driver (ie lowering utilization rates). The net result has been a uniquely severe cut in Uber's US average monthly driver earnings YOY in 2023, >15% for both Mobility and Delivery and delivery drivers (as reported by Gridwise). No other gig company -- not Lyft, not DoorDash, not Grubhub -- has come close to cutting US driver earnings by double digits.

This raises the obvious question, why aren't normal labor economics working in the US gig worker market...ie why isn't Uber experiencing a drop in drivers willing to sign up for a company that is cutting pay far more than competitors? A couple of factors may explain the current phenomena. First, is the precarity of financial circumstances facing lower-income citizens, particularly the growing number of recent immigrants. In most major cities, immigrants make up the vast majority of drivers on Uber's platform, and many of the economy's most vulnerable workers may have few realistic alternatives to supplement/earn income than jumping on Uber's relatively frictionless platform. Second is Uber's market power. It's reasonable to assume that most prospective drivers would be most likely to sign on with the dominant rideshare market leader to maximize perceived income opportunities. And, as I've noted in my reporting, Uber likely has the most sophisticated, AI algorithms in the industry to minimize their labor costs by targeting lowball trip pay at the least sophisticated, newest, perhaps most income-stressed recruits to their platform. The exploitable information asymmetry between Uber and its drivers may be unprecedented in business history.

I'm looking forward to your further analysis of Uber's economics, based on a deep dive of NYC data, subject to the caveat that, as you know, NYC represents a unique market situation, with capped driver supply, far more full-time drivers, higher driver eligibility requirements, etc.

In the meantime, let the record show that despite Uber's protestations on my findings on their take rates, the company has chosen not to disclose any meaningful metrics on its US ridehail operations: e.g. recent trends in average driver pay per trip, mile or hour, utilization rates, average earnings per online hour, etc. etc. I would also love to see a distribution of their US take rates. My hypothesis is that a significant proportion of their improving US profitability has been driven by the right hand tail of such a distribution, ie trips with a 50+% take rate. This rich source of profitability would take a big hit if minimum driver pay rate legislation (as currently scheduled to start in Minneapolis on May 1st) starts gaining momentum in other cities. This may explain why Uber (and Lyft) are threatening to invoke the nuclear option in abandoning their operations in Minnesota.

We live in interesting times!