Bipartisan agreement on any topic is rare, and it’s even more rare to see political legislators take an interest in supply chain issues. But, when these two phenomena converge, it often has to do with China. Over the last few weeks, as Shein’s public offering draws near, an increasing number of legislators are pushing for a closer look at this burgeoning mega-retailer, which has become a dominant online player in the U.S. and several other countries.

I’ve mentioned Shein quite often in the past, but I’ve never really delved into their operations or the nature of their business. So why the increasing scrutiny, and what is its root cause? Are there similarities with TikTok’s situation, with concerns primarily focused on surveillance risks? Or is there something more profound at play?

Today, I aim to delve deeper into Shein and the various features that make the firm so captivating, as well as examine the allegations against Shein and whether the company is taking any steps to address them.

Fast Fashion

Much has been written about the firm, so I plan to focus on better understanding their supply chain, since I feel there’s more mystique around it than real facts, and on identifying what’s novel and what’s simply good execution (not that there’s anything wrong with the latter).

The firm is associated with ultra-fast fashion or hyper-fast fashion, but to better understand these terms, we must look at the origin of fast fashion as an idea, which started from Zara.

The Spanish retail giant pioneered by introducing the concept of “Fast Fashion,” and revolutionized the fashion industry with its swift and agile supply chain. This approach allowed Zara to bring new designs from the sketchpad to stores in a matter of weeks, significantly outpacing traditional fashion cycles, which often span several months. Fast fashion is predicated on the idea of quickly capitalizing on the latest trends by rapidly producing and marketing new clothing styles.

Zara’s ability to reduce the turnaround time from design to shelf to just 10 days can be attributed to its innovative and highly integrated supply chain —Zara maintains tight control over every aspect of its operations, from design and production, to distribution and retail. This vertical integration enables the company to quickly respond to changing fashion trends and customer preferences. A key component to Zara’s strategy is the localization of its manufacturing bases, with a significant portion of its production taking place in Spain and nearby countries. This proximity allows for faster transit times compared to competitors who manufacture in Asia. Additionally, Zara employs an advanced inventory management system that tracks sales data in real time, enabling quick adjustments to production, based on demand. These strategies, coupled with a focus on small batch production, to create a sense of scarcity and urgency, have allowed Zara to set a new standard for speed in the fashion industry, while carrying little inventory.

Hyper Cheap Fast Fashion?

In contrast, Shein’s supply chain processes and principles aren’t publicly available and the company does not practice the same level of transparency. However, it is known for its rapid production and delivery cycle, as well as its adept use of social media and influencers, while maintaining extremely low prices.

Long-time readers of this newsletter know how I feel about tradeoffs... There’s always a tradeoff! And as the following graph (which I’ve shared before) illustrates: there’s always a tradeoff between a responsive supply chain and an efficient supply chain:

An efficient supply chain and a responsive supply chain represent two different operational strategies, each with its own benefits and challenges. An efficient supply chain focuses primarily on minimizing costs and maximizing productivity. It emphasizes high utilization rates, bulk orders, and long lead times to leverage economies of scale, making it particularly suitable for stable markets with predictable demand. A responsive supply chain prioritizes flexibility and speed to quickly react to changes in the marketplace. It emphasizes quick turnarounds, reduced lead times, and the ability to rapidly ramp production up or down based on fluctuating demand. This makes it an ideal strategy for volatile markets or industries subject to rapid shifts in consumer preferences.

While efficient supply chains are cost-effective, they may struggle to adapt quickly to market changes. Conversely, while responsive supply chains excel at handling market volatility, they often incur higher operating costs. Therefore, companies must carefully consider their market dynamics and strategic goals when deciding on a supply chain strategy.

What’s interesting about Shein is that their supply chain is both responsive and efficient.

Before exploring how that’s possible, it’s important to look at why the firm needs to develop both capabilities simultaneously.

The graph above shows the following: First, there’s a tradeoff between these two types of supply chains. Second, firms need to find the right supply chain to fit the level of demand uncertainty they experience, i.e., if demand is highly uncertain, you need a responsive supply chain.

This is especially true for Shein where customer demand is highly uncertain (more so than any other retailer) as they launch hundreds of new SKUs per week, making it extremely difficult to forecast demand for each SKU —it’s much harder to forecast demand for a “purple shirt with white polka dots” than for a simple purple shirt (and keep in mind, this isn’t the most hideous shirt when searching for the term polka dots).

But Shein’s demand uncertainty becomes worse when considering their unique marketing strategy, which is tightly built on TikTok and social media influencers.

Influencers, with their large and engaged followings, can create trends and generate demand for specific products. And you may argue that everyone uses TikTok, but Shein takes it to another level:

I am not a marketing expert, so I can’t assert whether or not this is a good marketing strategy (though it probably is), but from a supply chain point of view, it’s a complete nightmare. The fact that product demand depends on the whims of an influencer or TikTok’s algorithmic mood swings makes forecasting an almost impossible task.

So clearly, Shein needs to be responsive.

But looking at the prices, they are very very low. The shirt above is $13.49. In fact, if you only want a shirt with polka dots, you can get one for $4.5. So with prices this low, the supply chain must also be very efficient.

Shein: Hyper Fast Fashion by Micro Batching

So how does the firm achieve both speed and efficiency?

The main principles are micro batching, close supplier relationships, and data utilization for better decisions. All of these are tied to each other with the notion of micro batching, the most interesting and novel among them.

Micro-batching is a manufacturing technique in which production is divided into small batches rather than large-scale runs. This allows the manufacturer to test new designs in the market, and quickly scale production up or down depending on each style’s success, thus minimizing losses. This aligns with the fast fashion model where speed and responsiveness are paramount.

Let’s go a little deeper…

To comprehend the mechanics of Shein’s operations, we must understand the sheer scale of the numbers involved. The company reportedly launches about 2,000 new items daily. When Shein places an initial order of 50 to 100 pieces, the supplier usually suffers a loss. The question then arises: Why do suppliers agree to operate under such conditions? The answer is simple. If the SKU performs well, suppliers can anticipate significant follow-up orders that could make the venture profitable. Furthermore, Shein shares critical data with suppliers, enabling them to make informed decisions regarding raw materials, design capacity, and production. This shared knowledge allows suppliers to propose more profitable designs.

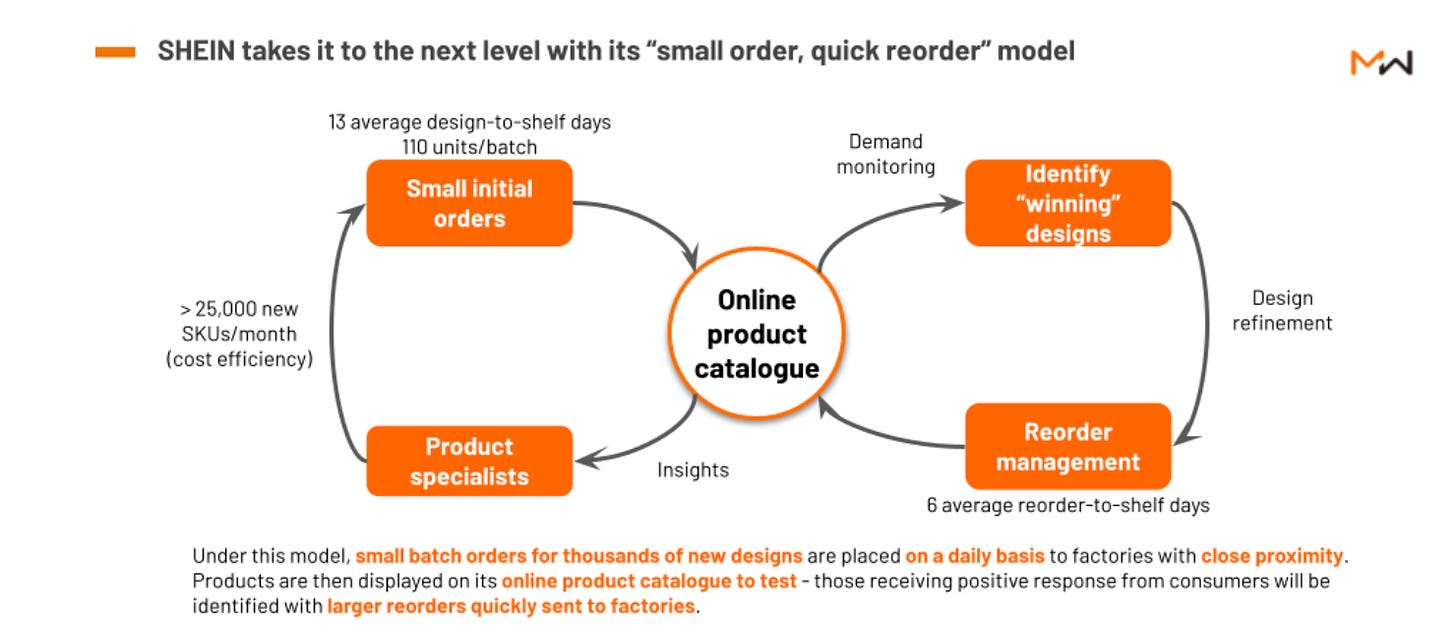

Shein’s supplier base consists of the following categories: Free on Board and Original Design. ‘Free on Board’ suppliers, who are approximately 500, produce designs that originate from Shein or from influencers associated with the firm. ‘Original Design’ suppliers, estimated to be between 20,000 to 30,000, send pictures of their designs to Shein’s internal buyers and upon approval of the design and subsequent samples, they receive an initial production order (typically small in quantity, between 50 to 100 pieces). It takes merely 13 days for a Shein SKU to progress from the drawing board to the shipping container. If a product is successful, they reorder and that takes only 6 days from order to shelf. This is nicely illustrated in the following figure:

The designs are often not original (one of the main criticisms Shein faces). If a competitor's product is successful, Shein leverages its data analysis and replicates it on its platform within two weeks, thus simplifying their own success path by minimizng their dependence on the competence of their in-house designers. Therefore, success no longer hinges on innovation and trend-setting but mainly on the ability to rapidly mimic your competitors.

But looking at the numbers, and a side-by-side comparison, we can see that Shein is not necessarily faster than Zara:

It just manages to have the same speed, with a significantly higher variety, and at a significantly lower cost. So maybe we should call it “Fast and Cheap Hyper Fashion.”

Unique Supplier Relationships

Most of Shein’s production takes place in small workshops scattered across China. This distribution contributes to the supply chain’s agility but also presents scalability obstacles. These workshops pose risks due to their inherent instability, including the threat of abrupt closure, which jeopardizes the overall supply chain’s reliability. Additionally, managing and expanding these workshops incurs considerable costs, possibly increasing overhead expenses.

Shein takes several strategic steps to navigate these challenges. To counter the volatility of these workshops, the company adopts the industry's shortest billing period and actively supports these workshops. It even offers funds for purchasing equipment and setting up new production facilities. Furthermore, Shein capitalizes on its proximity to the world’s largest and most sophisticated supply chain, insisting that manufacturers contracted to make its clothes are situated within a five-hour drive from its sourcing hub in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, as reported by Bloomberg.

Shein has also revolutionized this process by introducing a digital bidding system. Once an order is placed, the platform’s algorithm automatically recommends it to the most suitable workshop, so suppliers can accept the order online. This digitized process decreases transaction costs substantially, driving them close to zero.

But there’s one more aspect related to this supplier relationship and micro batching: the fact that suppliers will lose money if they manufacture a product that’s not successful since they’ll never receive a larger order.

This could be an interesting exercise in risk allocation, and more specifically, it can address issues related to double marginalization in supply chains, particularly in newsvendor-like problems.

Double marginalization occurs in vertical supply chains when there are multiple firms, each applying its own markup to the product. This effect essentially leads to a higher price and lower quantity for the final product than if the supply chain was vertically integrated.

In the context of newsvendor problems, this effect becomes even more pronounced due to the uncertainties related to demand and the potential surplus inventory. Those of you familiar with the newsvendor problem from my previous articles know it’s a classical theory used in operations and supply chain management to understand inventory management under uncertainty. For anyone unfamiliar, the problem involves determining the optimal quantity to order or produce so that demand is met, considering the costs of overstocking and understocking.

To better understand this, consider a two-stage supply chain, with a manufacturer selling to a retailer (newsvendor), who in turn sells to the final consumer. Each party aims to maximize their profit, which means the manufacturer will choose a wholesale price that maximizes their profit, and the retailer will choose an order quantity that maximizes their profit, taking the wholesale price into account.

However, when setting the price, the manufacturer doesn’t consider the effect of a higher wholesale price on the retailer’s order quantity. Similarly, when deciding on the order quantity, the retailer doesn’t consider the effect of their order quantity on the manufacturer’s profit.

This is the essence of double marginalization, resulting in higher prices, lower quantities, and less profit for the entire supply chain compared to what could’ve been achieved if the supply chain was coordinated or vertically integrated.

Simple ways to mitigate the double marginalization effect are implementing revenue-sharing contracts, quantity discounts, or two-part tariffs. Another option is for the manufacturer to operate as a newsvendor, which would require understanding and managing the uncertainties related to demand while also considering the costs of overstocking and understocking. That way, the manufacturer can internalize the costs associated with the inventory risk, thereby eliminating the double marginalization problem.

In Shein’s case, the supplier is taking the risk, getting the supply chain to be better aligned and again, reducing costs while also allowing for high responsiveness.

But to continue its success story, Shein needs its suppliers (which aren’t very financially viable) to maintain the ability to take risks ( by paying them upfront), and it needs to be able to use and share data with them.

Data-driven Decision-making

Like many modern retailers, Shein uses data analytics to inform its decision-making processes:

“Shein has also developed proprietary technology that harvests customers’ search data from the app and shares it with suppliers, to help guide decisions about design, capacity and production. It generates recommendations for raw materials and where to buy them, and gives suppliers access to a deep database of designs for inspiration.”

Shein’s innovative business model has intertwined social demand signals with supply chain operations, resulting in an incredibly efficient system. Consumer actions and interactions on their app, such as searches, views, and preferences, are meticulously tracked and analyzed. This rich source of data provides Shein with immediate and detailed insight into consumer behavior and preferences. For instance, if customers show increased interest in polka-dot shirts (why would anyone do that…), this information feeds back into the supply chain, informing decisions about what styles to produce and in what quantities.

This real-time data collection stands in contrast to traditional models like Zara. In Zara’s case, information from consumers would typically be funneled through store managers to the designers. This method, while effective, presents problems since store managers may not transmit all the information, or customers may not ask all the necessary questions leading to information that is limited, distorted, or too late.

By contrast, Shein’s business model circumvents these issues by being purely online. Everything a customer does on the app, from browsing patterns to repeated views of specific items, can be recorded, analyzed, and fed back into the supply chain almost instantaneously. In essence, the consumer’s behavior on the app provides a real-time weather forecast for the fashion market, serving as a guide for production.

Even though the consumer data may seem chaotic, when coupled with small, flexible suppliers capable of producing in small batches, it fuels a highly adaptable and cost-effective supply chain. As a result, Shein can accurately anticipate consumer behavior and demand trends, allowing it to maintain minimal inventory and avoid wastage. This data-driven and flexible approach to supply chain management has been instrumental in Shein’s meteoric rise.

And Being Based in China

Shein’s success is deeply intertwined with a specific policy shift in China that occurred amidst deteriorating trade relations with the U.S. In 2018, China waived export taxes for direct-to-consumer companies in response to a new round of U.S. tariffs. This change was particularly advantageous for Shein, which ships most orders directly from its warehouses in China. In the U.S., packages valued under $800 could enter duty-free since 2016, a loophole that remained untouched even when the Trump administration imposed new tariffs to make Chinese products more expensive.

This combination of Chinese tax support and the U.S. tariff loophole supercharged Shein’s growth. From 2018 to 2019, the company’s sales nearly doubled, and in 2020, sales increased again, rising by 250% to reach a staggering $10 billion due to increased online shopping during the Covid pandemic. Notably, Shein now pays neither export taxes in China nor import taxes in the U.S., giving it a significant competitive advantage, especially as consumer shopping habits increasingly shift to online.

It remains nearly impossible for international rivals to compete on equal footing. While any company willing to establish a subsidiary in China could technically avail the same tax benefits by shipping products directly to the U.S. in small-value packages, this is unlikely to occur. Major brands like Zara, which sells to stores and imports in bulk, cannot avoid U.S. import duties due to their substantial physical presence. As noted by Rick Helfenbein, former head of the American Apparel & Footwear Association, Shein has expertly navigated the system, enabling it to undercut competitors by approximately 24%, a substantial competitive advantage.

The final outcome from all these actions is that between 2020 and 2022, no other retailer grew as fast:

The Criticism

But Shein faces a barrage of criticisms on various fronts. One major area of concern is labor abuse in China. For example, a UK television documentary claimed it found incidents at two supplier factories. Furthermore:

“The inquiry was made following a Bloomberg report showing lab testing on two occasions last year found that garments shipped to the United States by Shein were made with cotton from Xinjiang. Washington has banned all imports from the Chinese region over concerns of forced labor.”

Another prominent criticism levied against Shein is related to intellectual property issues. The company has been accused of copying designs from smaller designers and brands, particularly from platforms like Etsy, and selling them without giving proper credit or compensation. This practice not only hurts independent creators but also undermines the principle of originality in fashion design.

Sustainability is another pressing issue as fast fashion is widely criticized for its environmental impact, and Shein, as one of the largest players, is a significant part of the problem. The business model of fast fashion encourages overconsumption by rapidly producing and selling low-cost items intended for short-term use. This leads to a high turnover rate of clothing, contributing to waste and pollution. Furthermore, the production processes involved are often resource-intensive and can cause considerable environmental harm.

What Does Shein do to Alleviate Concerns?

Shein first sought to clarify that the company is less reliant on the traditional Chinese supply chain. Instead of focusing heavily on imports from China, which may not be particularly sustainable, they’re striving to localize their operations.

But what does “localizing” mean?

The company is investing $150 million to build a supply chain in Brazil and to purchase increasingly larger quantities of fabric from India (where, interestingly, Shein was previously banned). They’re also planning to appoint a head of supply chain and logistics in the U.S. to bolster domestic logistics. Essentially the firm is nearshoring, which makes absolute sense for a company investing in responsiveness. Harder to justify in terms of efficiency.

In addition, the company is dedicating $15 million towards improving its supply chain compliance. This number is laughable, given that the company’s valuation is $100 billion. To put it into perspective, it’s akin to an average American family spending $100... and an American family spends $100 on holiday decorations.

This is what this is. Shein is spending on decorations otherwise known as signaling.

But signaling is only meaningful when it comes at a cost. So, in my interpretation, this investment of a seemingly paltry $15 million is the company’s way of indicating that they don’t particularly care.

Personally, while I appreciate their attempts at supply chain innovation, I’m not a fan of their approach. I’d much rather they invest in higher quality, and more sustainable products and materials. However, I should remind myself that I’m not their target customer.

It’s important to remember that this company knows its audience well. In today’s world, the aesthetic appeal of clothing, especially on social media, often outweighs the physical reality. The company thrives by providing a continuous stream of new designs for its customers to show off.

Back to government intervention: Even if the reason for this newfound attention is less than ideal, it could result in positive changes. One of the questions often raised is why we don’t see more companies becoming sustainable. I believe that one of the primary reasons is that customers simply don’t care. A case in point is Shein. It’s evident that their clothing is made of low-quality fabric, the overall quality isn’t up to par, and there are sustainability concerns. Yet, customer interest in the company continues to grow.

So is it possible that legislators’ interest in the topic will be a leading indicator of the public’s interest too?

More attention to labor abuse. More attention to sustainable practices.

Whether this will impact how the firm and its consumer base react, is a tricky question that I don’t yet have an answer for.

Shein can sell / promote clothes at a premium in Democratic countries based on freedom of speech and the wealth of customers who are not restricted on movement within their own countries. Micro CM model keeps costs low thanks to a lack of basic human rights - freedom of speech/ internal movement -in China's military dictatorship. This gives a competitive advatage in the double Gross Margin / CM game. Rural workers have to accept lower wages/ higher risk as they are prohibited from A) moving themselves or families within China to high earning areas B) complaining about it. Micro CMs are too small to bribe local officials to do anthing about it which international companies have to do via JVCs/ hiring larger CMs/ buying suicide nets etc.. Shien on you crazy diamond !

Thank you for another insightful piece. I think it's widely accepted that fast fashion poses significant sustainability issues. As an incoming college student, I've been a fan of Uniqlo's affordable prices and appealing styles, yet I'm now becoming more conscious of the potential ethical implications of supporting the brand.

Have you had the chance to delve into Uniqlo's practices? Given the durability and basic/timeless nature of their clothing, could this potentially offset their questionable manufacturing practices? I would love to hear your perspective on this!