Last week, Vroom, once a promising player in the online used-car sales market, announced a somewhat surprising shift in their business strategy: The company is planning to cease its e-commerce operations, halting both buying and selling on its website and to liquidate its current inventory through wholesale channels.

This decision comes in the wake of financial struggles, including difficulties in securing the necessary financing for expansion in a highly competitive and fragmented market.

Vroom went public early in the pandemic. The company’s market value peaked at above $8.8 billion in September 2020 but has since tumbled by more than 99%, as illustrated in the following graph:

You may not have heard of Vroom, but you’ve probably heard of Carvana, which isn’t doing as poorly if we compare the two firms over the last year.

Nevertheless, when comparing the two, after Carvana also went public, the latter isn’t doing that great either:

In the ever-evolving landscape of digital marketplaces, Carvana and Vroom once stood out as prominent examples in the online used-car sales sector. Following the trend of platforms revolutionizing traditional industries, both companies aimed to transform how consumers buy used vehicles, leveraging the power of technology. Carvana, known for its car vending machine concept, and Vroom, with its straightforward online buying process, have attempted to streamline and simplify the car-buying experience.

This approach directly contrasts the traditional, often cumbersome, in-person dealership experience. However, as time has shown with other digital platforms that faltered under market pressure and operational challenges, Carvana and Vroom now face their own critical juncture.

While this newsletter takes no joy in witnessing the failure of new firms, it’s an opportunity for us to understand the underlying problems that resulted in that failure. Specifically, platforms that have a heavy operations component make for interesting case studies.

Used Cars: Market Dynamics and Challenges

The evolution of car sales reflects a significant shift from traditional to digital methods. Historically, purchasing a car involved visiting multiple dealerships, engaging in negotiations, and often dealing with a need for additional transparency in pricing and vehicle history. The process was time-consuming and sometimes stressful for consumers. CarMax, which is considered the largest national used-car dealership –currently holding 2% of the U.S. market– tried to disrupt traditional car sales with transparent pricing and customer focus, but the process was still cumbersome.

It’s clear that the future of car buying is increasingly digital, offering a more convenient, transparent, and customer-centric experience. Online platforms like Carvana and Vroom have pioneered this change, enabling customers to browse extensive inventories, access detailed vehicle information, and complete purchases remotely, often providing the option of home delivery. This shift represents a fundamental change in the automotive industry’s consumer expectations and buying behaviors.

But the market also seemed ripe for such a change. In an article composed by McKinsey, the firm outlined two critical aspects that made such platform disruptions lucrative:

Even during recessions, the demand for used cars is not as volatile as for new ones.

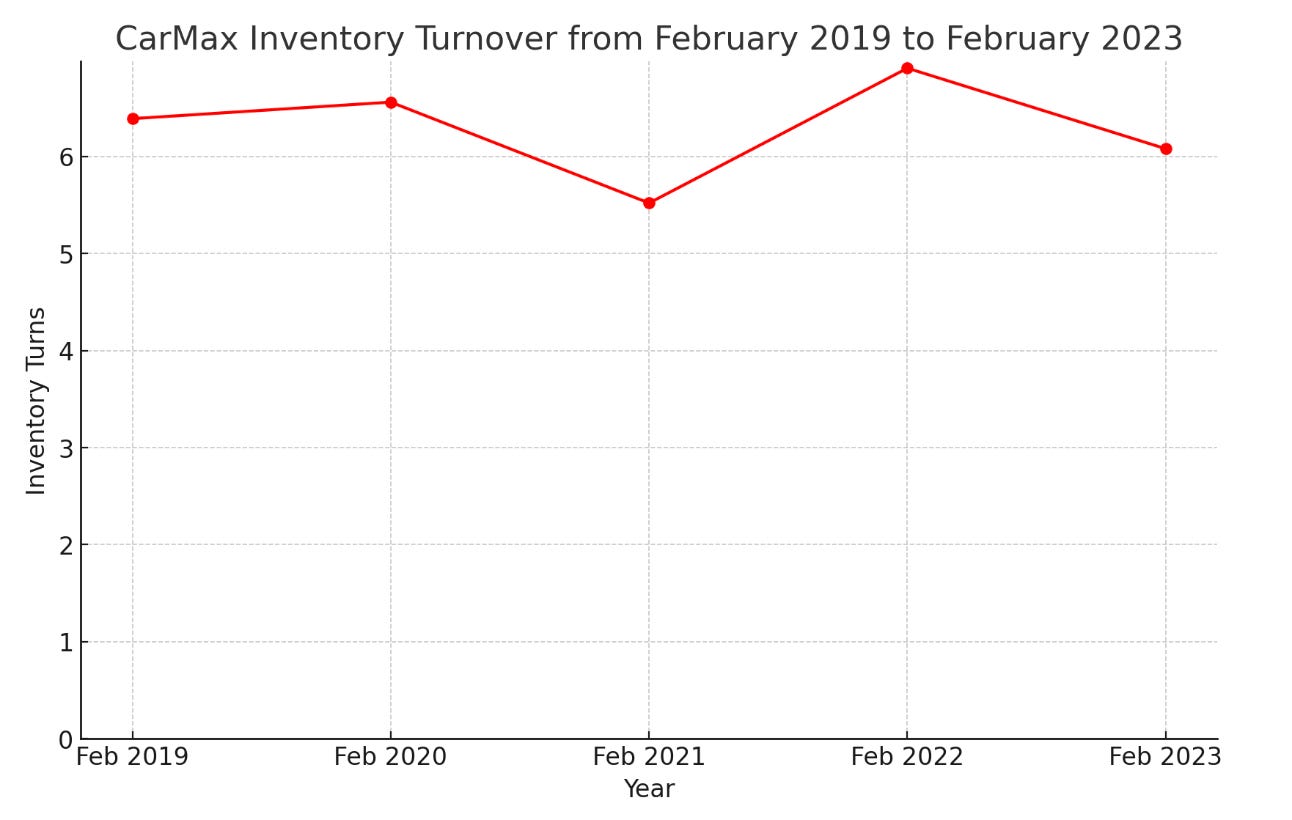

Furthermore, used vehicles are becoming younger (and lighter), which means that potentially, they will experience high inventory turns and higher prices:

A great starting point overall...

Financial Analysis

So, let’s compare Carvana, Vroom, and CarMax, focusing on two specific metrics: Days Inventory and Inventory Turnover.

Days Inventory: This metric indicates how long a company’s current inventory stock lasts before being sold. In general, the lower the number, the better, as this suggests efficient inventory management and faster sales cycles. In Q3 2023, Carvana significantly improved, reducing its Days Inventory from 82.03 (in 2022) to 47.54. In contrast, Vroom had a higher Days Inventory at 109.37, indicating slower inventory turnover. CarMax maintained a moderate level at 61.64.

Inventory Turnover: This metric measures how often a company’s inventory is sold and replaced over a period. A higher number denotes more efficient inventory management, and in the context of these platforms, it means that a car spends less time in their lots (and balance sheet), making the utilization of their capital more efficient.

In 2023, Carvana’s Inventory Turnover was 1.92 per quarter, showing a relatively rapid inventory turnover. Vroom’s inventory turnover was lower at 0.83 per quarter, suggesting less efficient inventory management than Carvana.

But what is truly worrying is the trend:

The graph depicting Vroom’s inventory turnover from 2018 to 2023 reveals a notable trend in their operational efficiency. After starting with a relatively high turnover rate of 6.88 in 2018 and a slight increase in 2019 to 7.06, the company experienced a sharp decline to 4.09 in 2020. Although there was a partial recovery at 5.19 in 2021, the downward trajectory resumed, dropping to 3.26 in 2022 and further plummeting to an estimated annualized rate of 3.32 (0.83 multiplied by 4) in 2023. This pattern suggests significant challenges in Vroom’s inventory management strategies, reflecting broader issues within the company’s operational model and market conditions. The decrease in 2023 indicates a critical point, potentially aligning with the company’s decision to cease its e-commerce operations.

Carvana’s trend, however, looks much better:

And CarMax? …Well…

We’ll analyze the drivers behind these metrics, but as leading indicators, there are multiple conclusions to be drawn here.

These metrics provide insights into a company’s operational efficiency in managing inventory, a crucial aspect of their business model. Carvana’s improvement compared to Vroom and CarMax indicates a stronger position in inventory management efficiency. And it’s easy to see why Vroom cannot survive under the current model: their inventory doesn’t move.

But these also show that CarMAx (a more traditional player) and Carvana (a tech native platform) are not all that different regarding a key operational metric.

Operational Challenges

The metrics mentioned above are leading indicators for financial success, but overall, they lag in terms of operational decisions, macro trends, and consumer behavior.

The operational landscape for online used-car platforms like Carvana and Vroom is riddled with challenges that are critical to their long-term success and customer satisfaction —among others, high inventory costs, management of aging inventory, and the hurdles of digital transformation stand out as significant obstacles.

1. High Inventory Costs: Both Carvana and Vroom have faced the challenge of high inventory costs. The nature of their business model requires a significant upfront investment in acquiring, reconditioning, and maintaining a large inventory of vehicles. This aspect becomes particularly burdensome in a fluctuating market where vehicle values can vary dramatically, impacting the company’s bottom line. Managing these costs while still offering competitive pricing to customers is a delicate balance that these companies must maintain.

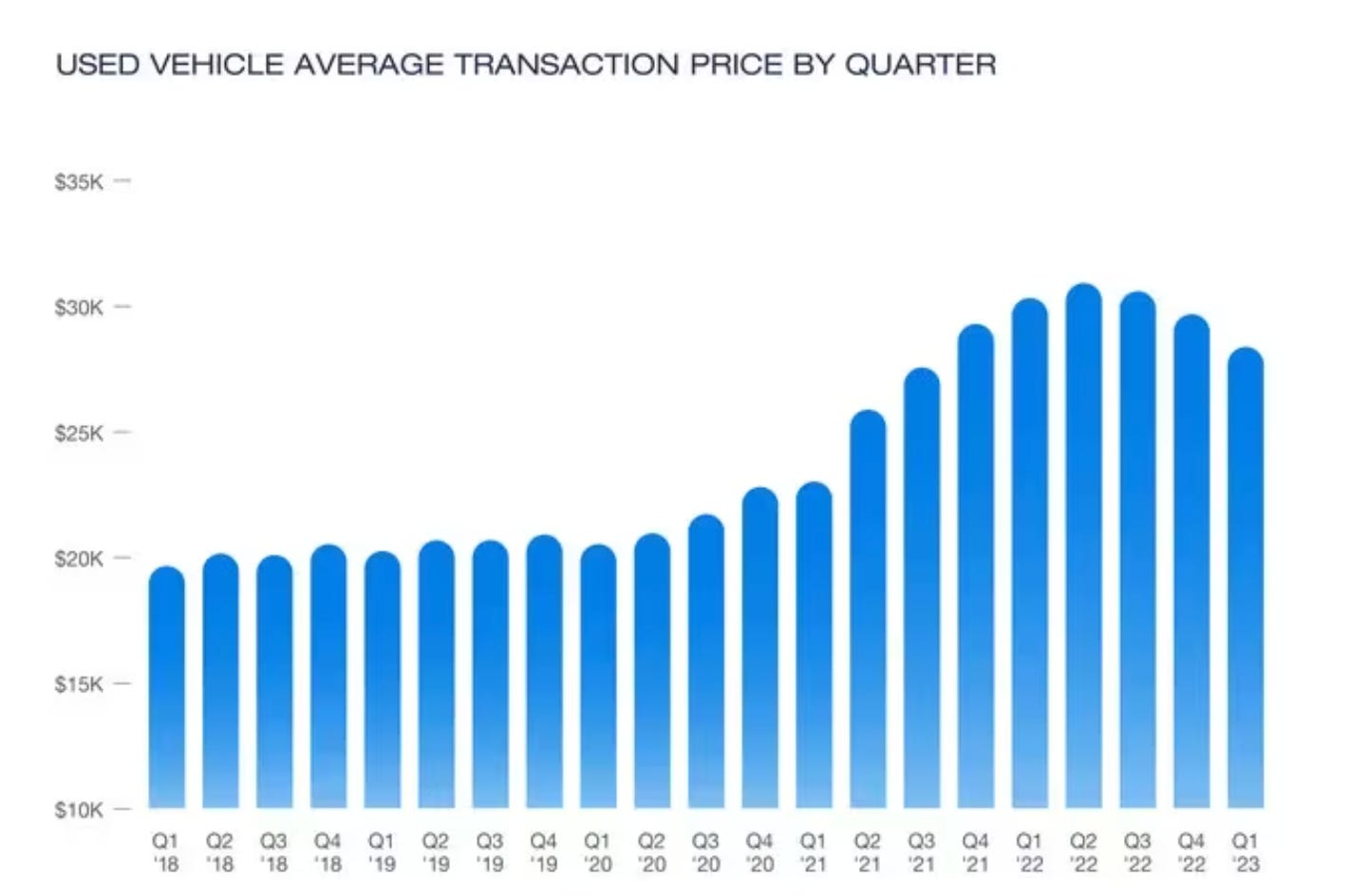

These companies initially benefited from the supply chain disruptions faced by major automotive manufacturers during the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to elevated prices for used cars. However, as these supply chain issues have been resolved, there’s a noticeable downward trend in both prices and demand for used cars.

This shift has increased inventory levels and costs for these firms, and a significant factor contributing to these increases is the current high interest rates, which add further financial pressure on operations.

2. Aging Inventory: Aging inventory is another operational hurdle. As vehicles remain unsold over time, they depreciate, reducing profit margins. For Vroom, this issue became particularly acute —in August, 80% of cars remained in inventory for over 180 days. In the pursuit of a diverse inventory, moving stock efficiently proved challenging and resulted in a significant portion of their inventory aging. This tied up capital and increased storage and maintenance costs, directly impacting their financial health.

3. Challenges in Digital Transformation: This is a recurrent theme when discussing platforms in this newsletter. Embracing digital transformation, while a strategic advantage, comes with its own set of challenges. Creating a seamless online customer experience requires robust technology infrastructure, effective data management, and continuous innovation to stay ahead in a competitive market. Both Carvana and Vroom have had to invest heavily in technology to support their online platforms, including developing user-friendly websites, secure payment systems, and efficient logistics for vehicle delivery.

4. Vroom’s Titling and Registration Issues: Vroom faced significant problems with vehicle titling and registration, and the company’s inability to efficiently manage this process resulted in customer dissatisfaction —a critical factor for any consumer-facing business. These problems, which led to increased costs due to customer rental car expenses, concessions, and legal and regulatory costs, resulted in strained customer relationships and increased operational expenses, further straining their financial resources.

In this dynamic and challenging environment, a critical lesson emerges regarding the fundamental nature of platform-based business models: the strategic importance of platforms focusing on facilitating transactions rather than absorbing the hefty costs associated with producing transactions or, in this case, acquiring and maintaining inventory. By doing so, platforms can leverage their technological strengths and customer reach without being weighed down by the capital-intensive aspects of inventory management. As Carvana and Vroom’s experiences illustrate, deviating from this approach can lead to significant financial strain that can possibly sink the ship entirely.

We witnessed something similar in Convoy’s story a few months back. This principle becomes especially pertinent for companies like Carvana and Vroom, who have grappled with the complexities of maintaining large vehicle inventories. The inherent risks of high inventory costs and the depreciation of aging stock are exacerbated in fluctuating market conditions, where companies have to navigate the dual pressures of altering car values and high-interest rates.

Scalable?

This naturally brings me to a simple question: Are these firms scalable?

I’ve previously presented my SCALE framework, so let’s jump right in.

To better understand Caravana and Vroom’s business models, it’s crucial to consider their scalability. Both companies operate as marketplaces, where increased sellers attract more buyers and vice versa. This dynamic can lead to significant cross-sided network effects and demand-side economies of scale, particularly if the companies offer a larger and more diverse inventory. A key aspect of their strategy involves leveraging national rather than local inventories, which can be more efficient for matching used car buyers and sellers, resulting also in supply-side economies of scale.

Alignment. Prior to Carvana’s emergence in 2017, the used car industry was mostly dominated by traditional dealerships that were characterized by limited accessibility for both buyers and sellers, price haggling, inconsistent pricing, and a lack of return policies. The onset of the online retail ecosystem presented an opportunity for disruption, which Carvana capitalized on by offering an end-to-end purchasing experience that aligned with consumer preferences.

The company’s strong product-market fit can be attributed to its comprehensive online platform, which provides a wealth of vehicle data, high-quality images, and efficient search tools, enabling customers to make informed decisions from the comfort of their homes. Additionally, Carvana introduced unique delivery options, further enhancing customer convenience and satisfaction. This transformation of the car buying and selling experience aligns with customers’ increasing preference for digital solutions, as identified by industry analysis from sources like McKinsey.

However, there are challenges to this approach. In particular, efficiency is a major concern, particularly in achieving a predictable path to a profitable business. Both companies are heavily influenced by the economic environment, with factors like interest rates playing a significant role. Additionally, there are substantial costs related to the ownership and processing of inventory.

A primary issue both companies aimed to address is the limitation of local inventories of local dealerships. By pooling inventory across various locations, they hope to offer more choices to consumers and improve how this inventory is managed. However, this approach has its own challenges, i.e., costs associated with managing multiple locations (since you do need to carry inventory close to consumers), even if you allow consumers to view a larger dataset and the logistics of vehicle ownership transfers.

Furthermore, disrupting the traditional car dealership model entails significant expenditure, particularly in the transaction’s ‘last mile.’ These costs, along with the inherent complexities of dealing with physical products, present obstacles to their business models.

Of course, the issue is exacerbated by the fact that they are dealing with price-conscious consumers (who would otherwise buy a new car), with ample options (including CarMax and the New Cars Dealerships), and a low entry barrier for small players.

In conclusion, while Caravana and Vroom have the potential to succeed in the used-car market, their success depends on how they navigate these challenges while showing that this market can be profitable. Their ability to manage costs and adapt to the economic environment will be crucial in determining their long-term viability in the industry. Unfortunately, neither firm has shown adequate signs of “readiness to scale.”

Future Outlook

Carvana’s strategy for future growth seems to focus on consolidating its strengths in the digital car-selling space while enhancing unit economics. By prioritizing profitability per unit over aggressive market expansion, Carvana aims to achieve sustainable growth. This strategy involves refining operational efficiencies, improving inventory turnover rates, and leveraging technology to enhance the customer buying experience.

But while the firm has shown some promise, it’s still very far from profitability.

In summary, Carvana and Vroom have tried to navigate the complex landscape of online used-car sales with innovative approaches but face distinct challenges and opportunities.

Vroom is at a crucial juncture, and I guess its days are as numbered as its current incarnation.

Carvana still shows some hope. With its emphasis on refining its business model toward profitability, Carvana appears to be on an improved path to sustainable growth, capitalizing on its digital platform’s strengths, but questions on profitability remain. The future prospects for these companies will largely depend on how well they adapt to the rapidly evolving market landscape, manage operational challenges, and respond to consumer preferences.

Carvana and Vroom’s journeys underscore the broader narrative of digital transformation in the automotive retail industry, highlighting both the immense potential as well as the inherent challenges of disrupting traditional business models. Along the same lines as other platforms, the initial innovation is digital transformation. Still, the main constraints remain (e.g., the need to deal with the physical world with real costs associated with carrying inventory and shipping it from and to the customer).

But these firms must also deal with an existing network of competitors that, while not as big, or advanced, or well-funded as these new platforms, have been there for many years and require the platforms to learn many lessons that these smaller dealers have already put behind them.

Great article as usual, Prof. I look forward to these every Monday!

Excellent takedown Prof. Do you think platforms should stick to technology and stay away from managing inventory? At the end of the day, customers want seamless experiences and not aggregators like Uber. Would love your thoughts.