Wendy’s Flips on Dynamic Pricing

Early last week, the CEO of Wendy’s announced that the burger chain intends to allocate close to $20 million toward implementing digital menu boards across all its company-operated restaurants in the U.S. by the end of 2025.

The main feature of these new menus (beyond AI of course, because everything is AI these days) is the ability to price dynamically:

“‘Beginning as early as 2025, we will begin testing more enhanced features like dynamic pricing and daypart offerings, along with AI-enabled menu changes and suggestive selling,’ he [Wendy’s CEO] said. ‘As we continue to show the benefit of this technology in our company-operated restaurants, franchisee interest in digital menu boards should increase, further supporting sales and profit growth across the system.’”

Let the backlash begin:

A senator, no less…

I recall arriving in this country as an immigrant and being promised the right to a reasonably priced lunch at Wendy’s every day. This country is heading downhill.

The firm immediately responded:

“Wendy’s says that it has no plans to increase prices during the busiest times at its restaurants. The burger chain clarified its stance on how it will approach pricing after media picked up on comments by CEO…. ‘Wendy’s will not implement surge pricing, which is the practice of raising prices when demand is highest. We didn’t use that phrase, nor do we plan to implement that practice,’ the company said in an email to The Associated Press on Wednesday… Wendy’s said that its digital menu boards ‘could allow us to change the menu offerings at different times of day and offer discounts and value offers to our customers more easily, particularly in the slower times of day.’”

So you see… they never used the term dynamic pricing (which they actually did), and they don’t plan to charge higher prices during the busy times of the day … they plan to give discounts during the less busy times of the day.

This newsletter is no stranger to fake outrage.

But we never settle for just outrage. We look deeper.

So let me make a bold (no pun) claim: Fixed prices are evil.

They’re bad for consumers, they’re bad for businesses, they’re bad for everyone.

Not only do they not make sense, but they’re actually not as common as we think. So why are people against any attempt to move away from this practice?

I know, some of you may say “they’re unfair.” And indeed, they may be. I’ve discussed this matter before, but today, I’ll try to delve deeper and show that dynamic pricing is not the problem. Or at least, it’s not the only problem.

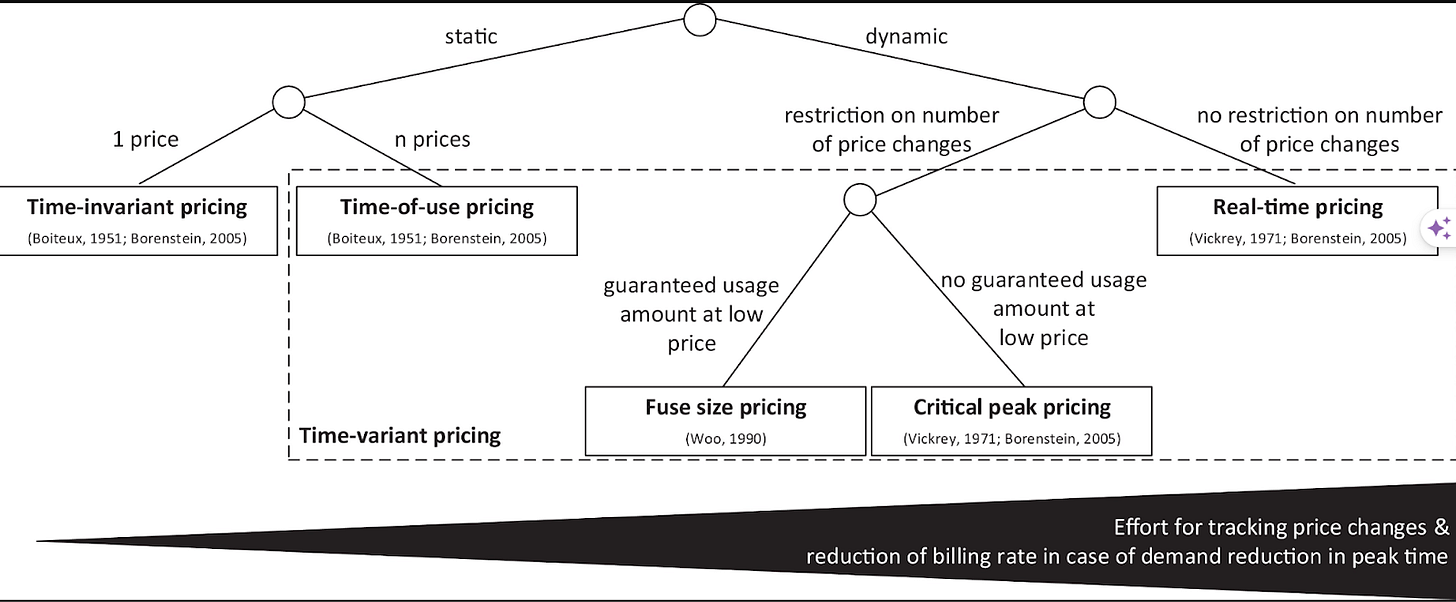

First, let me try to explain the existing alternatives to “fixed prices,” as they are shown in the following diagram. After that, we’ll discuss the love-hate relationship (primarily hate) with dynamic and variable prices.

Static Pricing

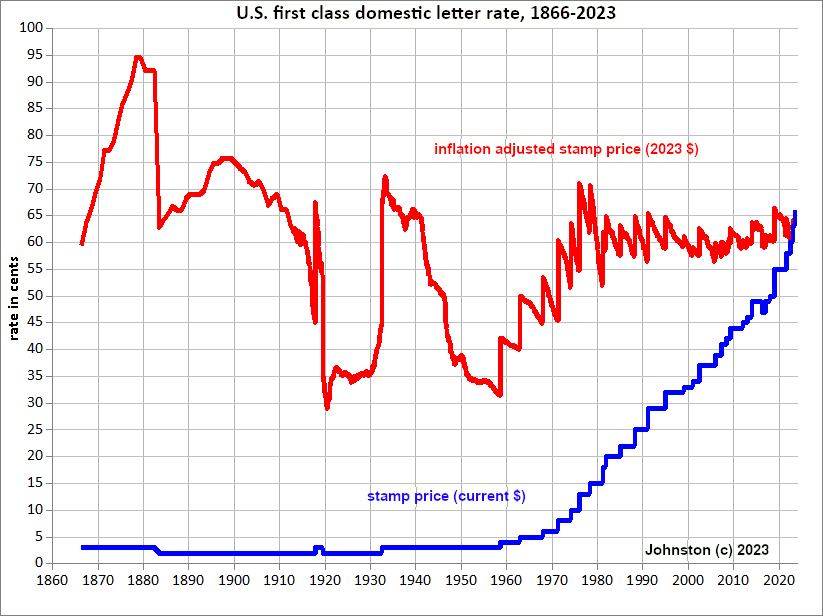

When I say “fixed pricing,” I mean static, time-in-variant pricing. An example you ask? I actually had a hard time coming up with one since almost every product has been or will be discounted at some point or another. However, one example could be U.S. postage stamps, and more specifically, domestic.

The price of course changes over time, but at any point in time, it’s fixed:

Before we move on to static time-variant prices, I should highlight one aspect that this graph is already missing —static, but location-varying prices.

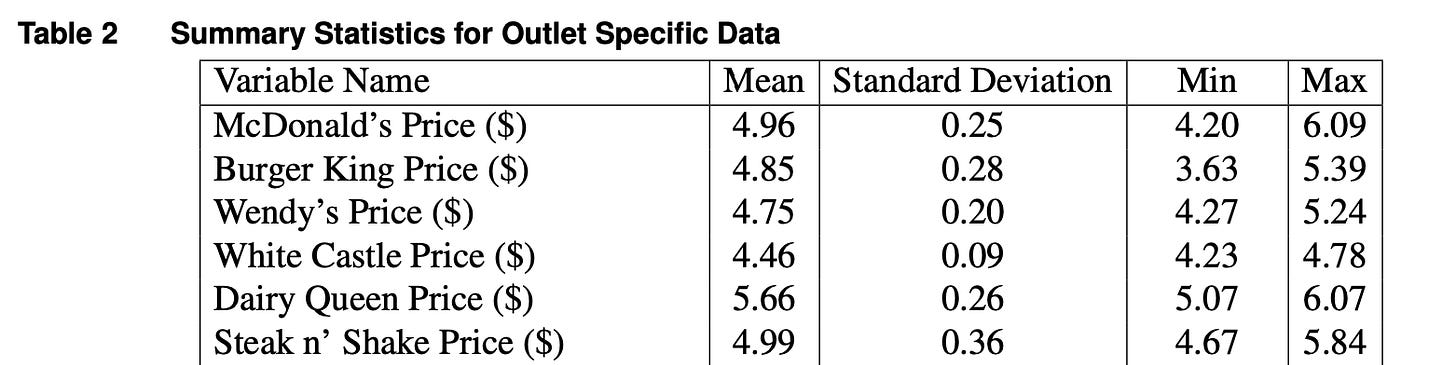

Guess which product is priced differently across the U.S.:

A burger. Particularly, the burger

Now, I know some may say, “But we use different currencies in different states (...) and there are different income levels in different states, so of course prices will differ.”

But let me tell you this: One can observe different prices even within the same county. In my paper with Awi Federgruen and Margaret Pierson, “How much is a reduction of your customers’ wait worth? An empirical study of the fast-food drive-thru industry based on structural estimation methods,” we called every single drive-thru location in Cook County (IL) and asked the price of a meal (burger, fries, and a drink) at the time (2011).

The results may shock you (and potentially the senior senator from Massachusetts).

Within the same county, a mere 20-minute drive from one point to another, we saw massive price differences —30% between McDonald’s locations and 25% between Wendy’s locations.

So if I live in a more affluent neighborhood, I’m price gouged. And if I’m a low-income worker working in an affluent neighborhood, I’m absolutely screwed.

So, if this is already a common practice, why aren’t we outraged?

First, we’re not aware. I’ve presented this paper on many occasions and people are always surprised. Second, weird as it may be, there’s a rationale behind it: level of income and convenience explain this variation.

Finally, the price is static —if you visit the same place day in-day out, you don’t notice any variation.

Time-Varying Static Pricing

Time-varying, yet static prices are also quite common (happy hour, for example).

Offering a discount in off-peak time is a frequent practice, and I don’t see people opposing that. The idea is simple and trivial: fewer people want and can have a drink at 5 pm, and the staff needs to be there earlier to prep, so offering a discount adds revenue, and potentially shifts demand from peak time when it’s difficult to serve everyone in a timely manner. Win-Win-Win: the restaurant (more satisfied customers and added revenue), the customers that come in earlier (less congestion and less expensive), the customers that come in late (less congestion and enjoy better service).

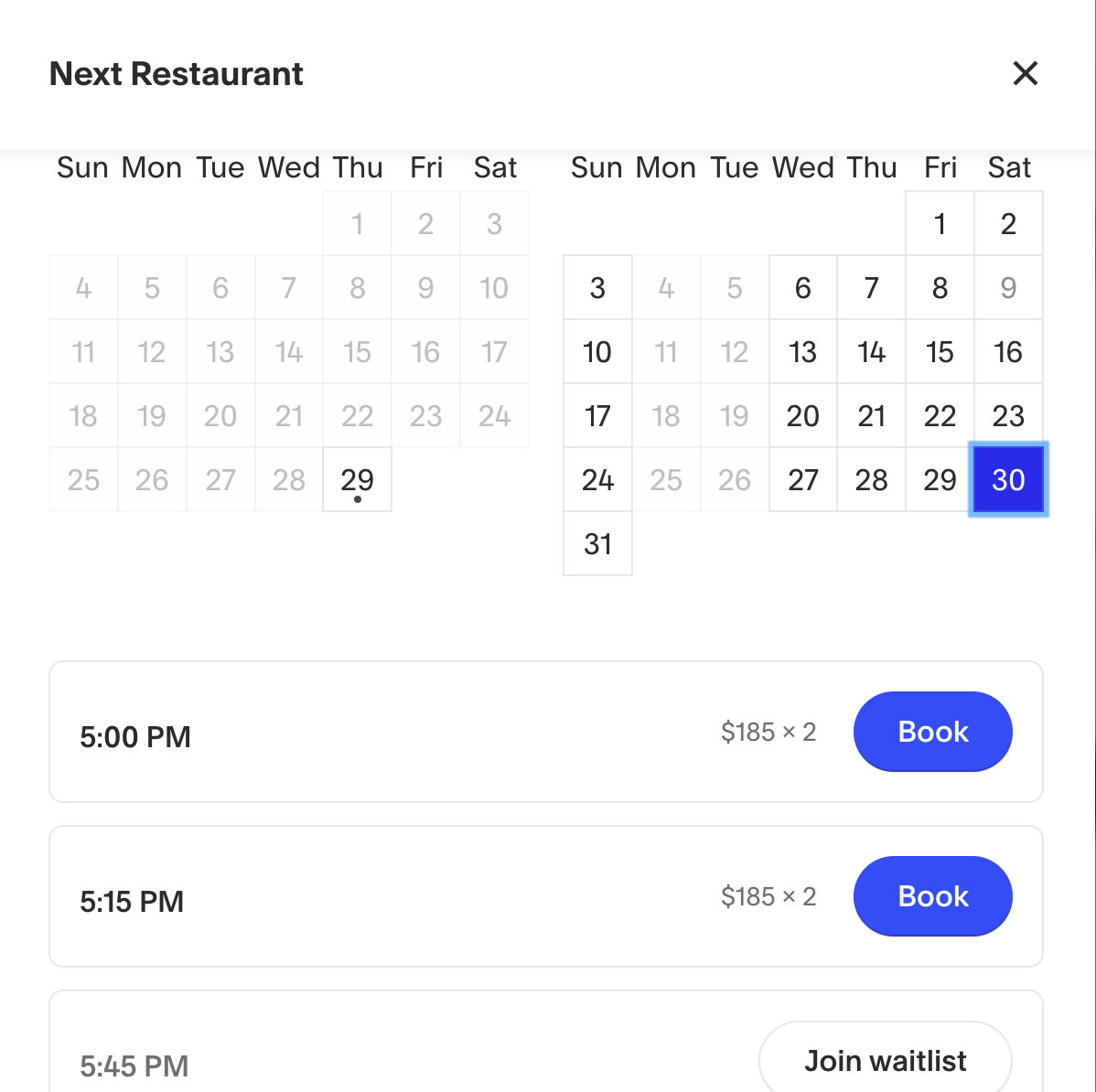

A good example for a firm that enabled variable pricing in fine dining is Tock, which started out of Next in Chicago.

Trying to make reservations for March 30th, I got the following screen:

However, when I looked two days prior:

The price was cheaper by $30 per person for the exact same meal and location (and most likely with nicer and less stressed staff). Where is the outrage here? Do I really have to pay $30 more on a (checks notes) $155 meal just because I work on Fridays and don’t like going out on Thursdays?

Nick Kokonas, the founder of Tock, says on the podcast “Invest Like the Best”:

“One of the talks I give to all of our new employees to talking to the industry is how Tuesday is not Saturday. And seven other things you already know but are doing nothing about it. It’s really obvious you don’t need to be an expert in the restaurant business to know every restaurant in the world. Probably you’re ninety nine percent with some anomaly are busier on Saturday night than Tuesday night. OK, so we have that.”

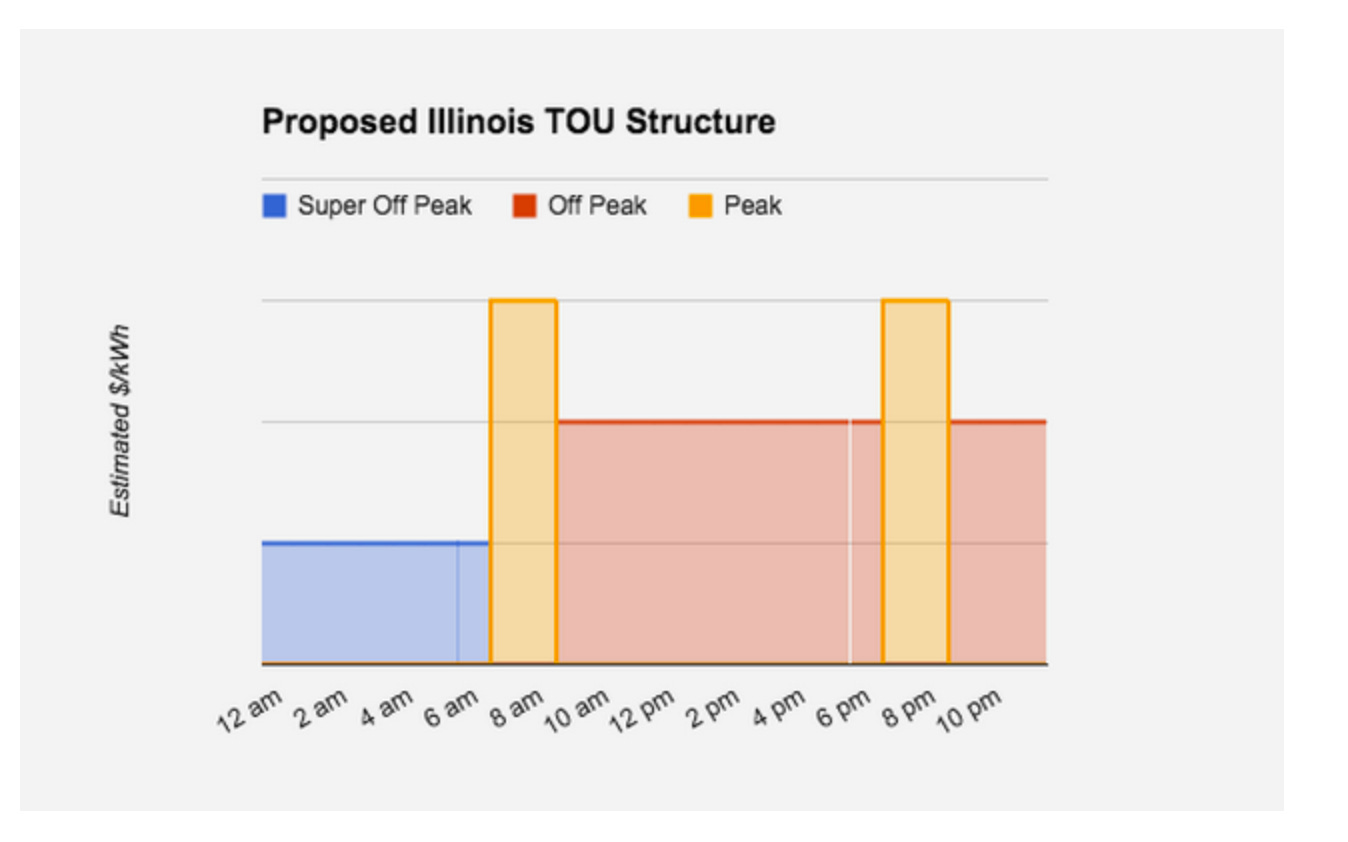

Another place where time-varying prices are used is electricity. For example, in Illinois, the Citizens Utility Board (CUB) and the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) have submitted a request to the Illinois Commerce Commission, urging that Illinois’ two primary investor-owned utilities be mandated to provide Time-of-Use (TOU) rates. Their proposal includes a three-block rate structure, as outlined in the chart below.

And again, it makes sense. During peak times (mornings and evenings), providers want to reduce the load on the infrastructure, since it cannot easily flex. By increasing the price during peak times and reducing the cost during off peak (e.g., late night), people can be encouraged to move certain activities like laundry or mining bitcoin, for example, to the later hours of the day.

Note that for the cases we’ve discussed so far, consumers are already aware of the price changes.

None of it is truly “dynamic” or “real-time response.”

Dynamic Pricing

Let’s understand what we mean by dynamic pricing.

Dynamic pricing is a more flexible and real-time approach where prices can change at any moment based on supply and demand dynamics, competitor pricing, time of day, and other real-time market conditions.

For example, airline tickets and ride-sharing services like Uber are classic examples of dynamic pricing, and the advantage is clear: it’s highly flexible. Prices are adjusted in real-time to reflect current market conditions, maximizing revenue or sales based on immediate demand.

Staying with electricity markets:

“In AEE’s PowerPortal database we have almost 500 TVR rates, for residential and small and medium commercial customers, of which almost 85% are TOU, under 10% are CPP, under 5% are PTR and around 3% are RTP. Arizona leads the nation in TVR participation, accounting for 30% of overall TVR participation.”

Only 3% are Real Time Response (fully dynamic price).

It’s clear that from the firm’s point of view, dynamic pricing is optimal, considering the ability to tailor the firm’s response to current market conditions. We’ve already discussed the benefits of this practice once in the context of The Cure (where I was in favor) and once regarding ski slopes (where I was against).

Personally, I liked Uber’s surge pricing. I much rather pay a higher price and find a ride to the airport than wave frantically at taxis with the hope that one of them is available, or worse, have drivers cherry-pick their rides based on what they perceive as optimal (the outcome in Israel where Gett, the equivalent of Uber, was not allowed to follow surge pricing).

People Hate Variable Prices

This isn’t a question. It’s a fact.

People hate variable prices and they hate surge prices. People also hate time-varying prices. They even hate discounts (primarily if they just bought the product before it was discounted).

Some of this hate is rational. But not all of it.

The paper “Why do consumers prefer static instead of dynamic pricing plans? An empirical study for a better understanding of the low preferences for time-variant pricing plans,” studies these preferences within the context of electricity markets in Germany:

“The results show again a strong preference for the time-invariant pricing plan, especially relative to fuse size pricing and real-time pricing. In these cases, at least 69% of respondents remain in the time-invariant pricing plan, even if the time-variant plans would offer expected decreases in the billing rate of 20% for an average household and the risk of paying more is only 5%. In contrast, on average 36% and up to 56% of the respondents accept the time-of-use pricing.”

The primary economic factors influencing decisions are perceived risk, the flexibility of technology use, and sensitivity to price. Among these, sensitivity to price plays the most significant role, contributing positively to the base effect by 39%. This suggests that individuals who are more price-aware are more inclined to switch to a pricing plan that varies over time.

Participants who demonstrate high flexibility in their use of technologies are 12% more likely to adopt variable pricing models, particularly time-of-use pricing plans, where the likelihood increases to 29%. Additionally, they tend to have fewer concerns about encountering higher billing rates.

Who then doesn’t like price variation?

Respondents who are averse to risk show a preference for the fixed pricing plan, with a significant negative impact on their decision-making (−0.64, or 18% when compared to other factors). Additionally, the perception of risk affects their views on the potential for savings, suggesting those with higher perceived risk place less value on the savings offered by providers compared to those who perceive less risk.

However, individuals with a high perception of risk also display a stronger inclination toward time-of-use pricing plans by 19%. The influence of expectations regarding off-peak usage is less significant, indicating challenges among respondents in either forming or expressing their expectations about their usage during off-peak times.

One of the most interesting observations is that price fairness considerations are less important.

How can you encourage people to adopt more price-varying methods?

Cost insurance represents a powerful means to increase preferences for time-variant pricing plans. Including this feature in an offering, substantially increases the switching probability from a time-invariant to a time-variant pricing plan by, on average, 10 percentage points for fuse size as well as real-time pricing and 15 percentage points for time-of use pricing.

Back to food and the dynamic pricing backlash.

Dear Senator, if you really care about the low-income population: For those who can’t afford the $185 Julia Child tribute at NEXT, you should allow dynamic pricing so that the wretched can enjoy it for $155. Don’t deprive the people of this country of their constitutional right to a fine dining experience.

Also, being against dynamic pricing doesn’t put you in favor of the low-income person. It puts you in favor of the risk-averse person who doesn’t like surprises.

They are NOT the same person.

Risk Aversion is about comfort, and as P.T. Barnum said: “Comfort is the enemy of Progress.”

Thank you for those nuggets of pricing wisdom!! I especially like the tree showing the types of pricing schemes. I think there might be another pricing scheme that could be included in your tree: auction-based or bid-based pricing. The consumers could place bids for what items during what time window and the restaurant could let them know if they won the offer. Or, it could be flipped so that the consumer places the offer and local restaurants bid for their meal. Restaurants could even offer up inventory days or weeks in advance to ensure a base level of utilization and reduce over-stocking.

Is the German electricity market the best data on this? If so, why is this unbelievably consequential area of economics under-studied. If not, do the results differ across categories, cultures, etc.?