Last week, Target announced that its profits will take a short-term hit as it takes several steps to get rid of excess inventory, from marking down slow-moving products to canceling orders to suppliers.

“‘We thought it was prudent for us to be decisive, act quickly, get out in front of this, address and optimize our inventory in the second quarter — take those actions necessary to remove the excess inventory and set ourselves up to continue to be guest relevant with our assortment,’ CEO Brian Cornell said in an interview with CNBC.”

A few weeks ago, Gap made a similar statement:

“‘Our inventory levels were significantly higher than we had hoped,’ O’Connell said, adding that nearly half of the unwanted increase was due to prolonged transit times that she expects aren’t getting better anytime soon.”

Walmart has made similar statements, and let’s not forget Amazon’s announcement regarding too much space.

People interested in supply chains like myself (experts, observers, etc.) had already seen this coming, but the speed at which it happened is staggering. The main reasons:

“‘People are shifting their shopping habits [and] are buying different things right now. That requires a lot of planning [and] a lot of adjustment to strategy,’ Arun Sundaram, senior equity research analyst at CFRA, tells Axios.”

People are buying fewer products (due to inflation) and different types of products (since returning to work and social life, and due to summer). So firms have to find ways to liquidate their inventory, both to allow space for new products and reduce their working capital, which is “stuck” with low-demand products.

Again, all this was already pretty obvious for several months, so the question is: Why did firms wait until they had too much inventory to do something about it? And since it was so obvious, was there no other way to prevent it?

Some aspects of this glut of inventory are rational, but others less so.

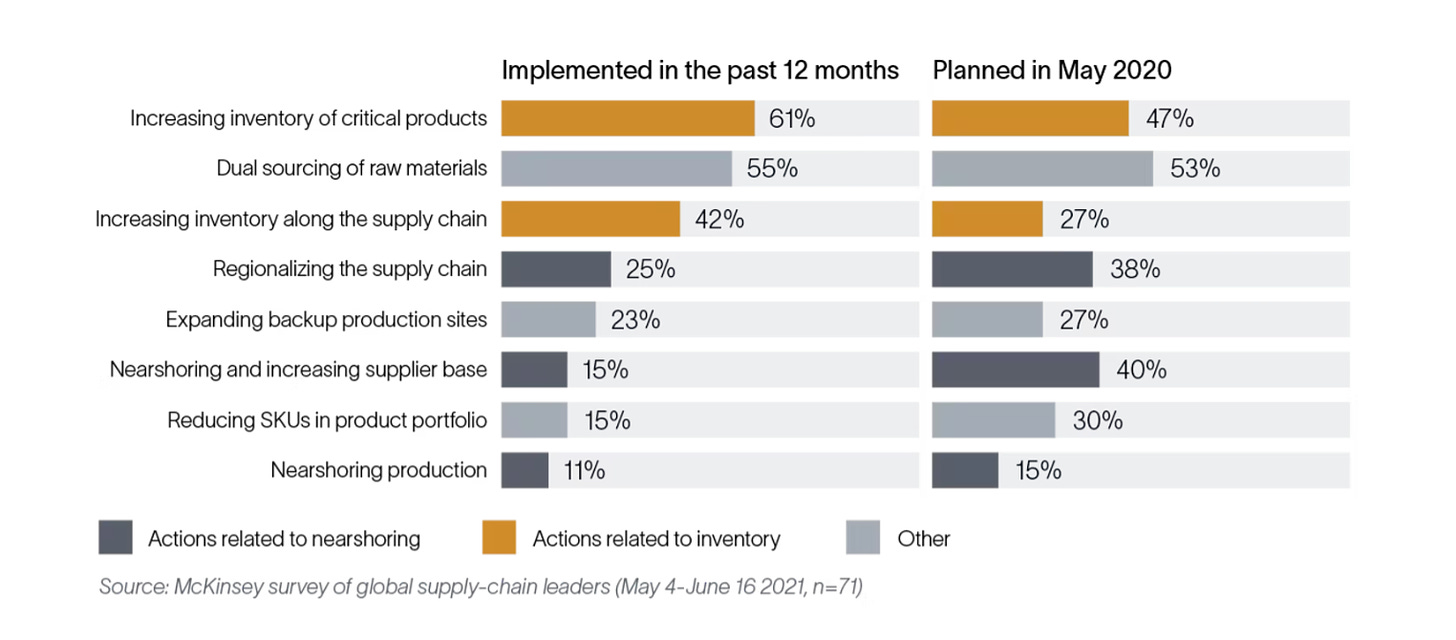

When firms knew things are going to be hard in 2020, they had suggested nearshoring, potentially regionalizing their supply chain, etc. The reality (based on the survey below) is that most firms increased their inventory, fewer firms nearshored, and fewer firms (than planned) reduced their SKU’s.

In other words, most just overreacted, and rather than take structural steps to improve their supply chains, they chose to order more.

And I don’t blame them. Over the last two years, interest rates were low, making the financial holding cost of inventory also low. Due to supply chain issues, lead times became longer, and shipping costs increased. Both factors forced firms to increase their orders, in order to spread their fixed costs over more units, and to better hedge against demand uncertainty, which becomes harder to forecast as lead times become longer. Finally, customers had more disposable income, and more time on their hands, so they were buying more products.

Under these circumstances, ordering more and holding more inventory made sense. Each one of the reasons above in and of itself would have increased inventory. Together, they just increased it to uncontrollable levels.

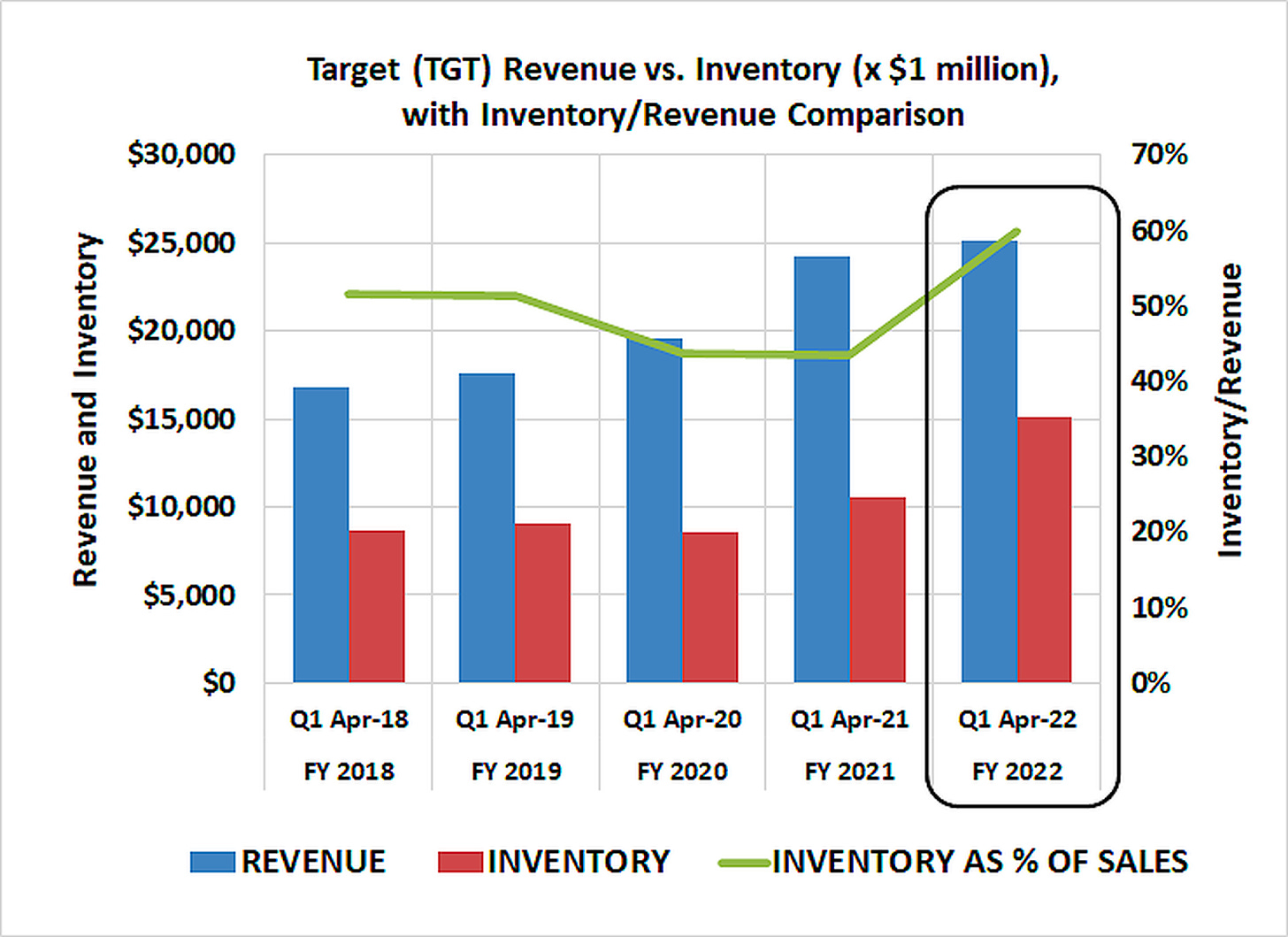

And indeed, as the following graph shows, Target has a lot of inventory, which is increasing faster than its revenues:

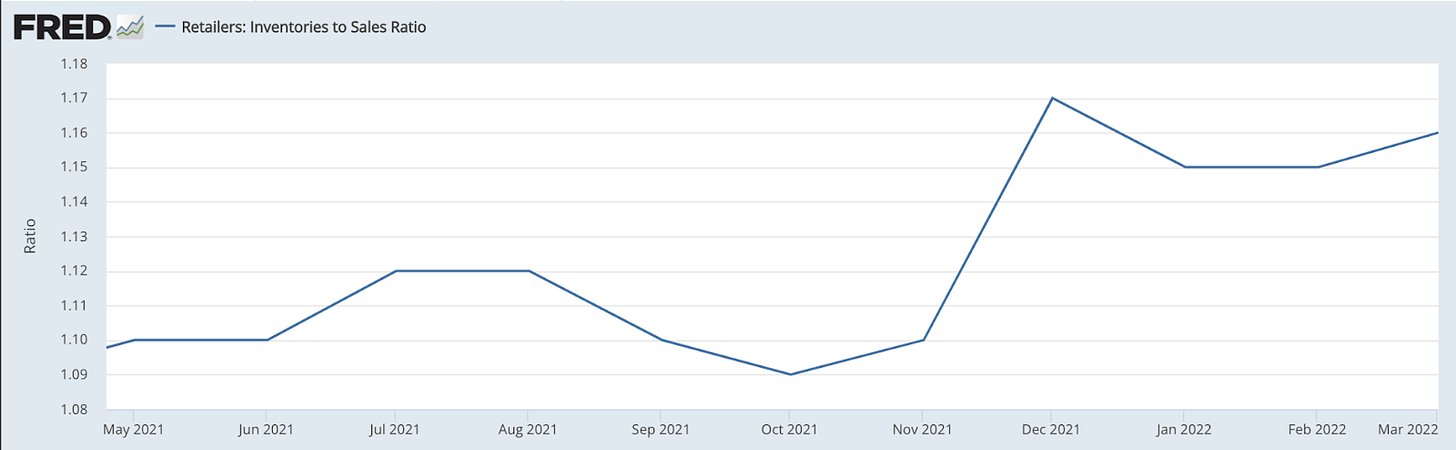

As we can see below, this is very close to what the entire economy is experiencing:

During my time in the Israeli military, there was a saying: “For every Shabbat there is a Motza'ei Shabbat.”

This loosely translates to: while you won’t be “punished” during the day (since it’s a day of rest), you should know that everything is recorded and there will be implications for every act of mischief and disobedience.

So every growth period also has its end, and now it’s the time to reckon with the fact that growth may stop, and the price needs to be paid for the long period of managerial imprudence.

Previous Cycles

But this is very much a story that repeats itself.

Let’s take a look at how things were during previous recessions.

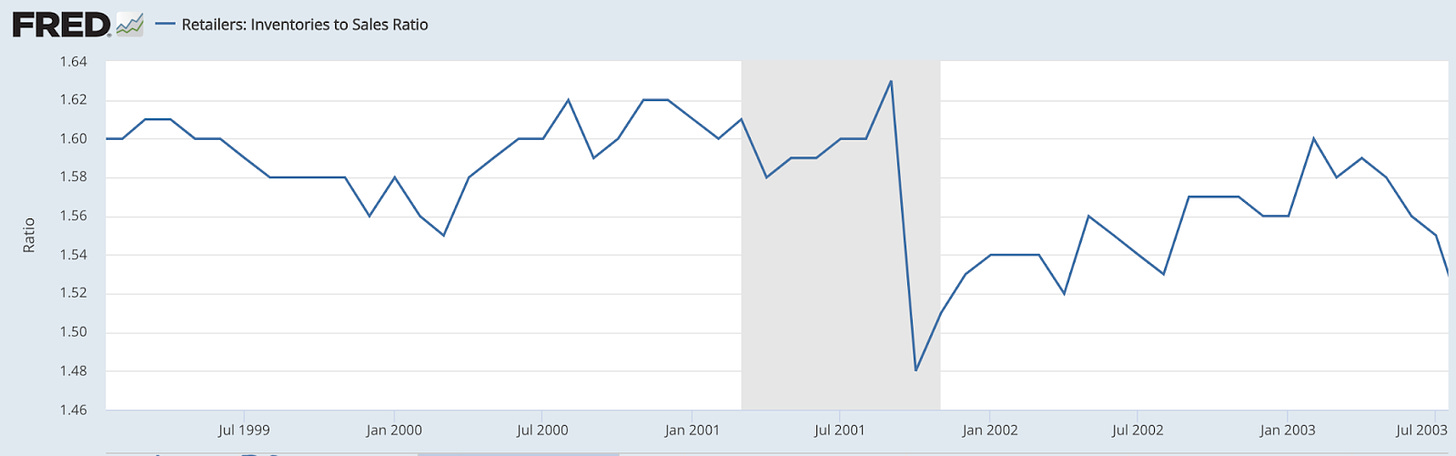

What we are experiencing now is not much different from what we have seen in previous recessions:

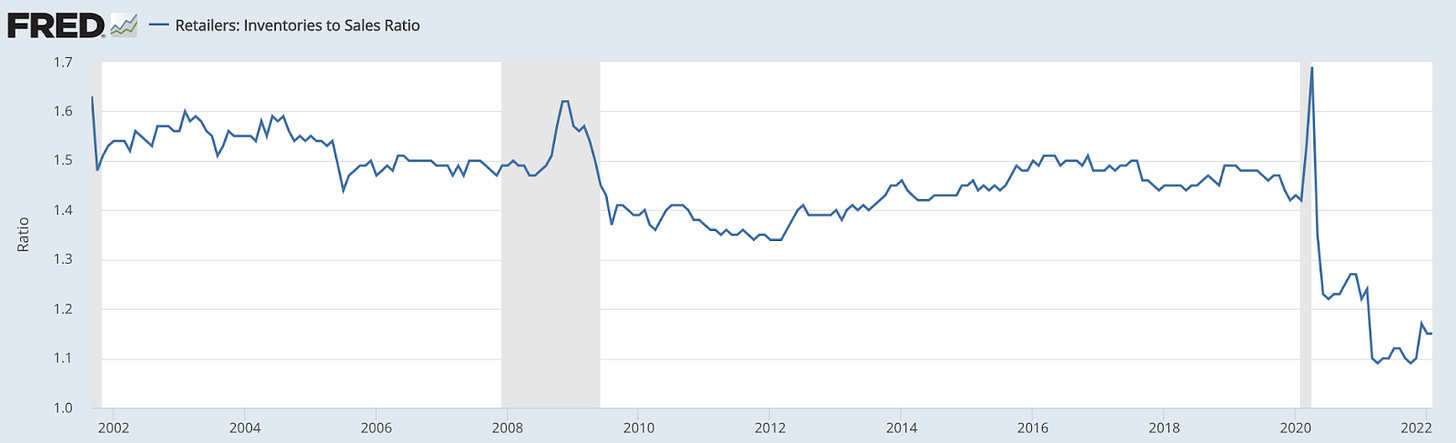

During the 2001 recession, we saw a mild increase in inventory to sales ratio (which is an inverse of “inventory turns,” and thus a good measure for how long inventory is being held), only to see a sharp decrease toward the end as retailers stopped ordering and liquidated their inventory as a way of cleaning up their balance sheets.

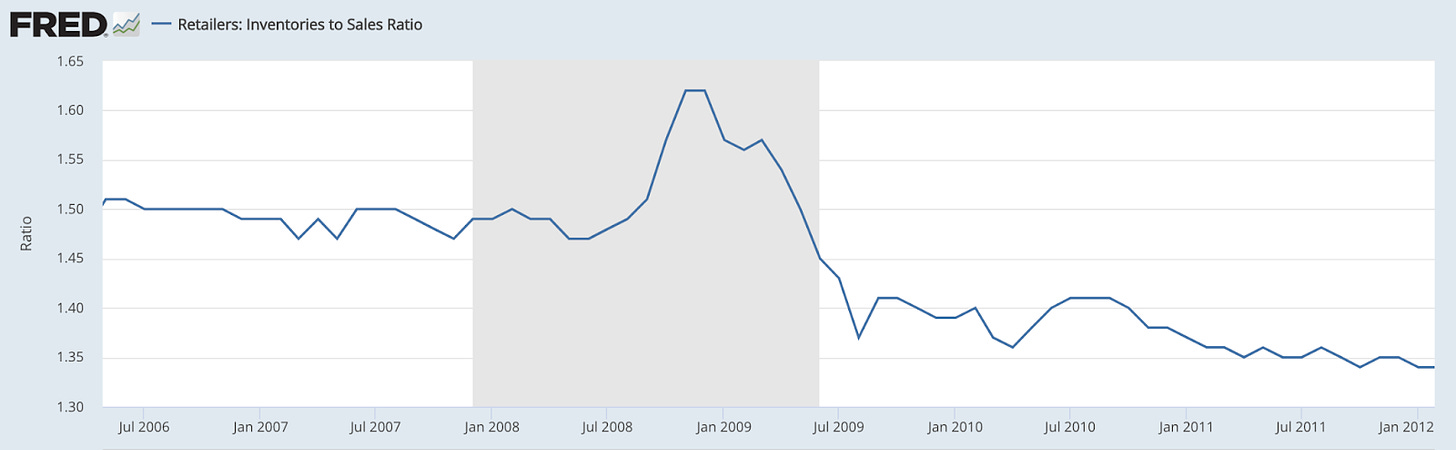

And the 2008 recession:

Here, again, the inventory to sales ratio is climbing.

As we see in these graphs, the amount of time inventory spends with retailers, is a lagging indicator of a recession. The peak inventory is actually in the middle of the recession, so if this is any indication, we are already deep in a recession even if we don’t know whether the inventory has reached its peak just yet.

The second thing worth observing is that while we feel that firms carry a lot of inventory, the actual inventory levels are still low from a historical perspective...very low from what we see in the next graph.

And this is probably the more worrying message here: the recession seems to be on the supply-side since we have a limited inventory of products and supply chain issues. In turn, this means that inflation is here to stay due to supply constraints, which means we are headed toward stagflation.

“Stagflation is characterized by slow economic growth and relatively high unemployment—or economic stagnation—which is at the same time accompanied by rising prices (i.e., inflation). Generally, stagflation occurs when the money supply is expanding while supply is being constrained.”

But this is only the beginning. If Target cancels orders, their suppliers are going to suffer and will also be stuck with a lot of inventory, which in turn will impact their suppliers. This is what the bullwhip effect is all about. And while Target can weather this wave of markdowns and write-offs, their suppliers (and their suppliers’ suppliers) will be heavily impacted.

So even though we are just setting off into the summer, we should all be bracing for a long winter.

Still enjoying your column, Gad, following from the sidelines. Especially with headline writing like this one! :) Kevin Brennan

Fast forwarding to December 2022 holiday season and happening to catch this blog as a new subscriber, I wonder what are the emerging trends in terms of structural investments by the large retailers to near shore their supply chain and in recalibrating their inventory with the new and emerging buying pattern? It was not rocket science to call out what was needed for resiliency was to reduce dependence on China, come up with a near shore and localization strategy, bet on stocking essentials (things that do not go out of fashion and can expect to have a moderate but dependable demand etc.) However, implementing these are easier said than done. I would love to learn of how the needles have moved. The low hanging fruit was to go and order more of what seems to be in demand from the same sources and that I can see has been happening everywhere.

With regards to Amazon's growing market share relative to the Walmarts and Targets, unless these retail giants can rebrand on convenience and variety and have reach out campaigns to their customer base , the train has left the station and an easy google search for a product will tell you that they are no longer on the top of the search. Even applies to Home Depot and Lowes. Do you agree?