I continuously get the following question: When will we be done with the supply chain issues we have been experiencing since the beginning of COVID?

My answer is usually: I really don’t know, but we haven’t seen the end of it.

Experts are now saying that the worst is yet to come.

“‘The risk posed by the Omicron variant is that we could take a huge step back in terms of supply-chain bottlenecks,’ said Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian Economics Research at HSBC. ‘This time, the situation could be even more challenging than last year given China’s increasingly significant role in global supply. Over the coming months we’ll experience the “mother of all supply chain” stumbles: an Omicron-driven stall in factory Asia,’ said Mr. Neumann.”

The Omicron outbreak in China is small compared to any other western country, but China has a Zero-COVID policy, which means that any detection of COVID, results in immediate lockdowns and massive testing campaigns. The impact on supply chains is devastating.

“U.S.-based Micron Technology Inc. said in late December the lockdown in Xi’an had reduced its workforce at its site in the city, affecting output of its DRAM memory-chip products. In Ningbo, Shenzhou International Group, a supplier to global sports brands including Nike, Adidas and Fast Retailing Co.’s Uniqlo, said some production sites were locked down from Jan. 3 after 10 cases were detected in Ningbo’s Beilun district.”

This is not only affecting manufacturing but also the ports:

“Ships looking to avoid COVID-induced delays in China are making a beeline for Shanghai, causing growing congestion at the world’s biggest container port. Shipping firms are making the switch to avoid delays at nearby Ningbo, which suspended some trucking services near that port after an outbreak of COVID-19, according to freight forwarders and experts.”

China is the world’s biggest trading nation as well as a worldwide manufacturing hub. The ability to keep its factories functional during the pandemic has been absolutely crucial for global supply chains.

But what is interesting is that the tone of many of these articles is critical, blaming China for the impact of its Zero-COVID on global (and local) supply chains.

China and Global Supply Chain Since COVID

So, first, it is important to recognize that this Zero-COVID policy allowed Chinese manufacturers to remain open while many countries experienced much more significant and nationwide outbreaks and lockdowns.

One of the interesting aspects of the pandemic was the significant demand shock it imposed on supply chains. We saw higher demand for everything, from cars to laptops to toys: people bought more products and fewer “experiences,” as things like vacations, restaurants, or hotels were no longer accessible.

During that time of increased demand, relying on China as a manufacturing center became even more pronounced. At the beginning of the pandemic, as China shut down almost all its economic activity, and while other countries seem to be going the other way (causing the great Kettlebell shortage, for example), many people (including myself) thought that this was the turning point regarding China’s global role in terms of its supply chain centricity.

This, however, has not been the case. The world became even more dependent on China, at least in the short and medium-term. As the following graph indicates, since the dip in early 2020, global imports from China have been, to a large extent, increasing steadily.

Even in the US, albeit somewhat less clear and at a lower level than pre-COVID.

But if the reliance on China has increased, in part due to its state capacity to keep its economy functioning, isn’t it odd that we are blaming the exact same policy for the impending “mother of all supply chain crises?”

If you read this newsletter frequently, you know that I’m definitely not a government apologist.

I blame governments for many of the mistakes associated with COVID. The fact that we don’t have enough COVID tests is definitely something that the government should be held accountable for. The deployment of vaccines and the spread of (mis)information around them, are definitely things that governments should have handled better.

But blaming a country that decides to protect its citizens because you disagree with the way they choose to do so, is quite problematic.

Supply Chains and States

There are many reasons I find it problematic, but the main one is that I view this as an attempt to defuse the responsibilities of the supply chain managers and their leaders.

The majority of people were shocked when COVID started, and rightly so. This was unprecedented in any possible way. But very quickly we realized that this is not going to end soon. We also “knew” that we are going to see many more small and large shocks to local and global supply chains, and these shocks may sometimes be correlated across regions and sometimes lagging.

Shortly after the COVID outbreak, I had a discussion with my colleague Santiago Gallino during a public Wharton event. This was back in May 2020, almost a decade ago…amiright?

We both predicted that the recovery was going to be very long (longer than what most people anticipated) with a lot of uncertainty about where demand and supply were going to arise.

The point we made during our talk was that in such circumstances, it is important to rethink the supply chain and adjust for the new nature of demand and supply shocks. It is wiser to think more about how to build resilience against these types of shocks that resemble tremors following an earthquake.

What was said at the time was that we first need to focus and solve the immediate urgent problem, and that it will take a while until we can reshuffle suppliers, shift things, and build a more resilient supply chain.

But we are now entering the third year of the pandemic (two full years since COVID hit China and soon thereafter the rest of the world), and I am still seeing more of a firefighter mentality rather than a “back to the drawing board” concept.

In other words, firms still don’t realize that this is the new reality and that maybe it’s time to somehow rethink the supply chain.

And this brings me to my next question of how we should think about states and nations in the supply chain. Firms have to remember and recognize that when dealing with other countries they’re also dealing with the unpredictability of each country, and this is true for almost every regime. In some cases, it might be because the ruling party changes. In others, it may be because the ruling party, although the same, changes its priorities. But in many ways, states are quite unpredictable.

But one of the interesting facts is that, as far as its policies regarding COVID are concerned, China has actually been very much transparent from the beginning. The Chinese government announced the Zero-COVID policy pretty much from the get-go.

Zero COVID and Hedging

The main issue with this policy, in terms of supply chains, is the type of uncertainty it imposes.

Supply chains don’t like uncertainty in general, but they like binary uncertainty even less.

Demand shocks tend to be continuous. If there is an increase in demand during one week, it is possible to learn from it regarding what to expect in terms of demand the following week. It may not be higher, since it may just be “noise,” but it’s not unlikely to be higher. We have good forecasting tools to deal with situations like these. The same holds for other continuous variables such as shipping prices or yield issues at different plants.

But lockdowns, which are accompanied by plants and port closures, are binary. The fact that the plant is operating this week, is a strong indication that it’s likely to be operational next week too. But “likely” does not mean it’s certain. And exactly this uncertainty makes it very hard to anticipate and manage these closures. We could treat them like random events, but that would be a mistake given that we know the reason behind them.

So first, we need a way to predict these disruptions, and then think about their implications, how to mitigate them, and hedge against them.

The hedging or risk management strategies for these types of disruptions are vastly different but the key is early detection and diversion.

For example, the impact of ports closures is an increase in pricing of shipping.

Since November, we have been hearing that after the holidays things will go back to normal and that we have already seen the worst in August. But notice the increase in prices around the end of November when the Omicron variant emerged. It’s very slow initially and may just seem like “noise”.

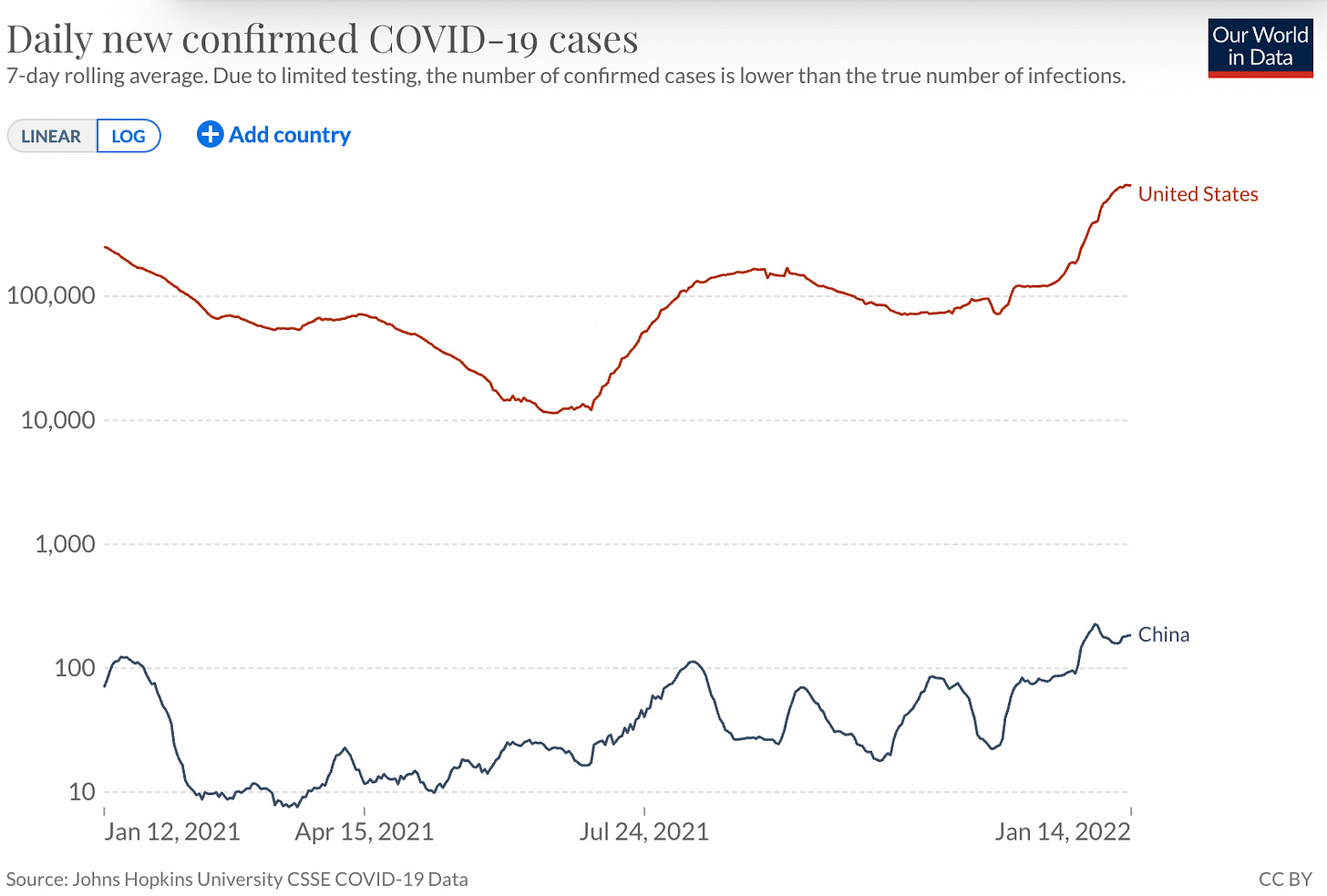

But in fact, we can see that it is a lagging indicator of COVID cases in the US (even if not in China, given the small number of cases and the somewhat unreliable reporting).

Risk management strategies need to have three components: a strategy or action plan, the ability to execute the action plan, and an early detection process that will allow the actions to be executed fast (before the actual situation arises).

Strategy can refer to building a global supply chain that is flexible (vs a more dedicated one, centered in a specific country, low cost, and nearshore). Execution means that you can carry out your plan to deal with different shocks and disruptions when they occur. Early detection means that you are mobilizing resources (logistics and people) and activating the process before you are at the peak of the crisis when everyone is in panic and overreacting.

So, early detection is an important aspect. Knowing where your suppliers are is another.

When creating a risk management strategy, having multiple suppliers in multiple continents, with potentially different connectivity levels is crucial. For example, many firms used Vietnam to hedge against risks in China, only to realize that there was a high correlation in the disruptions they were experiencing due to the connection between the two countries. Canada and the US have a similar correlation. Thinking more strategically about suppliers will be a capability that firms will need to develop.

But this is going to be the reality of global supply chains over the next decade. Government actions will have a significant impact on performance, more than the small savings a firm can make by choosing the right supplier.

However, this does not absolve supply managers from optimizing their supply chains. Rather it means that they need to develop the capability to have a more holistic view of the impact of global players on their supply chains.

And also understand that different disruptions should have different mitigations and hedges.

Over the last few years, (even before COVID) supply chain teams started hiring lawyers to better understand the legal implications that their decisions may entail. It would be interesting to see supply chain departments hiring or getting advice from geopolitical experts and epidemiologists, post COVID.

And as supply chain complications remain among the top 3 business concerns for CEOs in 2022, I would like to see the type of thinking I outline here elevated to the top of the organization, and not only to the head of supply chain.

I am curious to see how our field evolves and what your opinions are about how supply chains should move forward.

Our reliance on China has become more apparent than ever before. My thinking re: this is that food shocks were a big problem for quite a few areas in the US - the way this was prevented in most places was by means of having supply chain diversity which ultimately buffered many cities against food shocks. To buffer the US in such a way and ensure we don't end up like a food shocked city, we should try and diversify our international supply chains. The only question that remains is how feasible a move away from Chinese-based supply chain would be in the first place... Regardless, exceptional and thought-provoking article as always!

Excellent! This is exactly the type of thinking we promote.