A few weeks ago, the WSJ had an interesting article about Wonder, a meal-delivery service whose most recent funding round valued it at $3.5 billion and is expanding rapidly.

I have mentioned Wonder in one of my previous posts. The firm’s main innovation is that the meals are partially cooked in a commissary, a central kitchen, and then delivered in “mobile restaurants” by a “chef-on-the-road” who finishes off the order curbside. The company has bought the off-premises rights to some of several “celebrity chef” restaurants, such as Bobby Flay.

The WSJ article is not (only) about the innovative business model but (also) about the complaints it generates:

“Mr. Dafis, 52 years old, has fielded complaints about truck noise and truck smells, about trucks blocking driveways and trucks polluting the air, not to mention concerns the trucks steal business from local restaurants. He said many issues could be resolved if neighbors simply talked to one another, but there is also an element of folks disapproving of their neighbors’ environmental choices. “There’s a lot of that going on in South Orange and Maplewood,” he said.”

The response from Wonder:

“Wonder officials say the company complies with state and local laws and responds quickly to complaints from customers—and their neighbors. The firm says that because its trucks carry refrigerated food it is exempt from state laws that limit idling to three minutes. And because its food is par-cooked in a central kitchen it says it is exempt from town ordinances that regulate food trucks. ‘These are not food trucks,’ Scott Hilton, Wonder’s chief executive, said. ‘And they’re not just delivering food either.’”

This highlights an issue I addressed several weeks ago: the pressure new business models put on existing infrastructure and on the quality of life for people that are not consumers of these services.

Traditional Restaurant Business Model

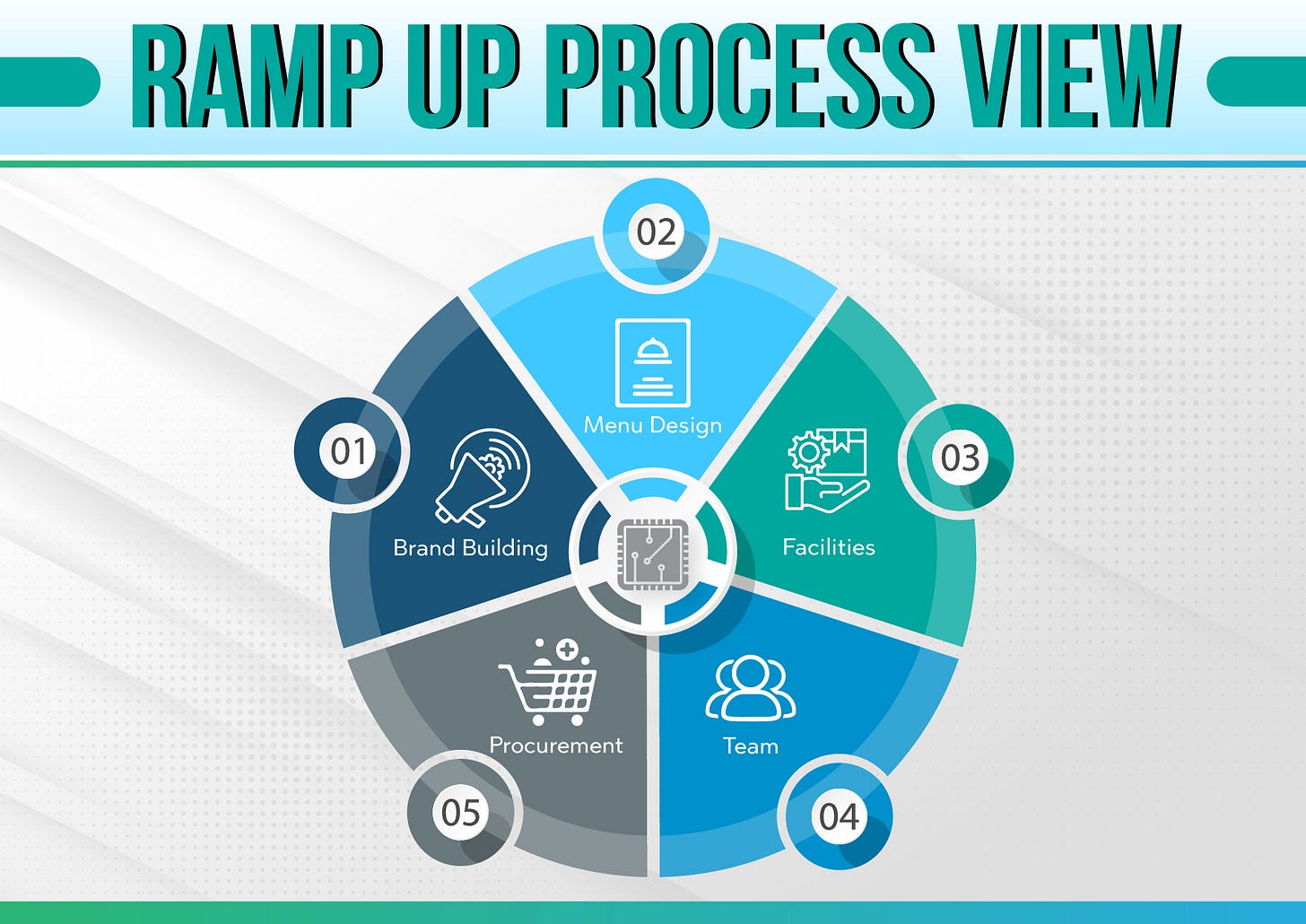

When building a traditional restaurant, the owners usually go through the following steps: they build a brand, they design the menu, they look for a facility (they rent the space and then lease or buy the necessary equipment), they put together a team (chef, waitstaff, etc.), and lastly, they procure the food ingredients. All this is done regardless of whether there is even a single customer to serve.

In order to actually make money, restaurants need to acquire customers, take orders, cook the food, serve or pack the food, and then somehow deliver the food (for those who offer that service).

The traditional model is one where the entire “ramp-up” process, from brand building to sourcing, is done on-premise, usually in relatively expensive real estate. Again: all of these costs are incurred regardless of whether customers actually arrive.

For traditional restaurants, customer acquisition, which is done either using the real estate location (walk-ins) or a reservation app (Resy or Open Table), order fulfillment, order intake, cooking, packing, and delivery all happen simultaneously when customers come to the restaurant. The “delivery” is done by the waitstaff.

The main problem is that all of these activities are done in the same place and in anticipation of demand. So it’s an expensive, slow, and very time-consuming process for the customer since they need to go to the restaurant. Also, once you choose a location, your options are fairly limited.

The advantage is that the time from order taking to food “delivery” is short, so the food is served warm and fresh. If something is not to the customer’s liking, they can change or replace it, order more or adjust the order on the spot. You don't need to know every detail and can get inspired by what other people have ordered. Not to mention the advantages of an ambiance (albeit this may not apply to every restaurant).

DoorDash and Delivery Platforms

The first disruption of traditional dining was introduced by platforms such as DoorDash, Grubhub, and Postmates (among others). I have discussed them before, but I am taking a slightly different angle here.

How have they changed this industry? The “ramp-up” process has largely remained the same: the restaurant incurs the costs and risks associated with the facility, the labor, and the ingredients. Customer acquisition may be done through the platform where the customer searches by type of food (e.g., pizza) or by the restaurant (e.g., a specific pizza place).

The main change, however, is that now the order-taking process happens on the app, and the order delivery is done by the delivery platform (since food prep and packaging still happen at the restaurant).

The main advantage that this model offers restaurants is the ability to reach more customers. And for customers, it’s the ability to have more options.

The main disadvantage for each party is also clear. Restaurants pay a fairly high fee to the delivery platform, still incur significant costs, and are now using very expensive real estate, primarily as a kitchen. For customers, there is no question that food from a delivery platform is never at the level you expect at the restaurant. This is evident from the reviews you can read regarding the same restaurant, with high reviews from people that dined in but low reviews from those who opted for delivery. Not to mention that DoorDash and the like just make too many mistakes.

Cloud Kitchens

The latest evolution we have seen is the idea of a cloud kitchen. The term doesn’t mean the same for all places, but the idea is that you don’t need to have the kitchen in a place that is attractive to customers to walk by and sit.

The comparison is taken from one of the main providers of cloud kitchens:

Based on their estimates (which are clearly biased), the main change is in the “ramp up” process: restaurants still take all the steps but run at lower risk levels since they utilize a much lower cost of real estate, fewer people, and thus much less capital. On the order processing side: it’s the same as before, but now the cloud kitchen is where they deliver from.

Overall, a much more cost and capital-efficient process which utilizes economies of scale to generate better unit economics. But these “restaurants” are much more beholden to the platform (since there is no way of knowing them outside the platform), and the food quality is still not great, potentially even worse since they are located on the outskirts of cities to reduce costs.

Wonder

This is where Wonder comes in.

As I mentioned above, Wonder’s meals are partially cooked in a cloud kitchen and then delivered in a van, while the final prep happens near the customer’s house. As I mentioned, the restaurant has bought the rights from a few famous restaurants, so they offer famous LA restaurant menus in NY. You cannot mix and match, though (which is probably part of their contract with these chefs).

What changes in the process: The restaurant still needs to build the menu and the branding (not sure who Bobby Flay is, but I guess he must be someone since everyone keeps mentioning him). Wonder, however, bears all other costs.

But from this point on, everything is done by Wonder. The entire ramp-up and the ordering process are also done by Wonder, and they are also the ones who acquire the customers, cook, pack and deliver.

What’s the advantage for the restaurant?

On the ramp-up, the restaurant can just deal with the branding and menu building, and Wonder is the one that takes the risk of ingredients and team building, and it probably gets a cut from the revenue from this point on.

For Wonder (when compared to delivery platforms), the unit economics of the trucks is expensive, and it bears the entire cost of customer acquisition all the way to delivery. On the ramp-up side, they bear all costs from the facility, team building, and ingredients. So it’s a very expensive and capital-intensive business (which is why the firm raised so much money). But Wonder controls the entire relationship with the customer, which brings me to the customer.

As per the WSJ article, people like the food since it is being prepared just before, they get it, and customer service is also good overall. For example, when the food is being delivered, you receive it from a “chef” wearing a coat and Wonder hat, not a Dasher who is in a hurry and is delivering the cold Pizza that was supposed to be delivered to someone else. Overall, the offering, while limited at this point, is of high quality (meaning high visibility) restaurants that are not always available locally.

Wonder-ful Externalities

But there is a new aspect that we should consider in our analysis: those who are impacted by the service indirectly since they aren’t the ones ordering the food.

In traditional restaurants, the impact is limited. If you don’t walk by the restaurant, you don’t smell the oven, and you are not impacted by the congestion near the location. There is a lot of food waste, and overall it’s probably not the most efficient use of resources, but the impact is minimal.

Regarding platforms such as DoorDash, delivery drivers definitely can become a nuisance, but most of the efficiency and inefficiency of food prep remain the same.

Cloud kitchens have the opportunity to reduce the carbon footprint and air pollution (as well as noise) since they are located on the outskirts (potentially) of cities. But we still have delivery people (usually cars or smaller vehicles).

What about Wonder? The food is partially prepared in the cloud kitchen, but there is definitely food prep done in the van, and the cooling equipment necessary for this requires the engine to be running. I was trying to estimate the additional carbon footprint of having the van idling (standing with the engine operating). There have been numerous studies that show how harmful idling is. It does not cause more pollution than driving, but the question is: Why not time the food prep in a way that the truck doesn’t have to be idle? It’s clearly significantly more polluting than a regular delivery service.

As for food waste: the firm claims it donates food waste, but this can be done by any restaurant.

The main advantage of a cloud kitchen is that it pools the capacity of many restaurants creating economies of scale, but it results in potentially lower quality food. Wonder un-pools the food prep and makes it even worse than in a restaurant: you make one meal at a time for each family. So any efficiency of pooling is lost.

On top of that, it creates havoc in a way that impacts those who do not wish to get served by this firm. And things seem only to get worse: The WSJ article mentions that Wonder’s fleet of 200 vans is expected to number in the thousands in two to three years.

My take: I don’t think this is the future we want to see. I believe we want to have tradeoffs: if you want to save time, you should be willing to either cook at home or order potentially lower-quality food. If you want to have a good meal, either cook it at home or go to a restaurant.

I like innovation and think there is an interesting angle here, but not at the expense of the public sphere and our neighbors.

Interesting article, Professor. My prediction: Wonder's fleet will NOT "number in the thousands in two to three years". This is an expensive, niche service that won't scale well.

Working against them are:

(1) annoyed neighbors

(2) folks with environmental concerns

(3) "foodies" who will point out the quality gap between the "authentic" restaurant version of dishes vs. the one made by "some guys in the back of van" (although your analysis largely focuses on purely-cloud restaurants, Wonder's webpage suggests many partners are IRL restaurants, such as Maydan in DC and Fred's in Atlanta, so the ability to compare exists)

(4) the obstacle that matters most, customer acquisition cost from trying to stand out in an extremely saturated marketplace

How many more VC-money-burning meal prep or meal delivery services do we need?