DoorDash Acquires Wolt: Consolidation, Scale, and Density

Earlier this week, DoorDash announced the acquisition of Wolt, a Finnish food delivery firm, for $8.1 billion. The market response was quite favorable, and DoorDash’s stock went up by 11.58% after the announcement.

For those who are not familiar with Wolt, it is one of DoorDash’s main competitors in the European market. My main familiarity with them is from Israel, a place I visit pretty often. In the days before Wolt, it would not be odd to have delivery times of one or even two hours and with overall inferior service (forgotten items, cold food, tipping only in cash, etc.). Wolt changed all of that with their rapid acquisitions of restaurants and drivers, as well as their relative customer-centric approaches.

Very quickly, seeing multiple Wolt drivers at the same time became a common sight in Tel Aviv (as the photo above demonstrates).

Of course, with the fast growth came criticism of Wolt’s model and the increase in fees (from 20% to almost 30%) collected from restaurants, but overall, it was a game-changer for many cities in Europe.

But there is nothing unique about their model. It’s a gig platform for food delivery, just like DoorDash, Deliveroo, Delivery Hero, Caviar, Uber Eats, or Postamates, etc.

The CEO of Delivery Hero, a Berlin Based competitor to these firms and an early Wolt investor, offered his own take on the matter:

“‘It’s an exceptionally high price compared to any other M&A that has happened but I think for DoorDash it makes strategic sense,’ he said, because it gives them a fast entry into Europe. ‘We were obviously involved in the process, it’s just that DoorDash would be able to go way beyond what we could justify so we never made an offer.’”

DoorDash is double the size of Delivery Hero, but not an order of magnitude bigger.

So why did DoorDash acquire Wolt?

Has the food delivery industry consolidation started already?

The Industry Consolidation Life Cycle

DoorDash knew the speed with which they needed to move through the “Consolidation Life Cycle,” which ultimately played a role both in the acquisition and their willingness to pay for it.

What is this life cycle?

In a classic article about industry consolidation, the authors describe the following four-stage model: “Industry Consolidation Life Cycle.”

Stage 1: Opening. The first stage begins with a sole start-up or monopoly branching out from another industry. At this stage, the focus is more on accumulating market share rather than becoming profitable. But as other companies catch on, the monopolistic aspect is replaced and the combined market share of the 3 largest companies settles between 30% and 10%.

Stage 2: Scale. At this stage, the focus is on building scale. Some of the most prominent companies begin to acquire competitors or merge among themselves, creating the main players. The article predicts that at this stage, “the top three players will own 15% to 45% of their market, as the industry consolidates rapidly.”

Stage 3: Focus. This is the period where “megadeals and large-scale consolidation” come into play. Stage 3 companies aim to become one of the few industry-wide leaders by “expanding their core business and continuing to aggressively outgrow the competition.” Out of the 5-12 prominent companies, the top 3 will, at this stage, control between 35% and 70% of the market.

Stage 4: Balance and Alliance. At this final stage, the few major players own as much as 70% to 90% of the market, which causes the industry concentration rate to level out and even dip a bit. The article claims that “large companies may form alliances with their peers because growth is now more challenging.”

The article points out that: “Ultimately, a company’s long-term success depends on how it progresses through the stages of industry consolidation. Speed is everything.”

Although the article does not include the food delivery industry, this still seems like a pretty good depiction of the stages that DoorDash and others are going through.

So, at which consolidation stage are we?

Globally, I would say we are probably at stage 2 (Scale), but locally in the US, I believe we are closer to stage 3 (Focus). I already discussed the decision DoorDash made to expand beyond its core.

Let’s try to better understand the impact of scale in this industry.

Scale Based Moats

Food delivery systems are able to create a competitive advantage by creating a moat.

What does this mean? Let me provide some background information on moats.

When I teach scaling operations, I usually tell my students that firms should accelerate their growth rate only if they can create a scale-based moat.

If you are asking yourself why the term “moat”, you probably studied business or economics in the ’80s or ’90s. In 2021 we use the term moat to describe barriers against competition. We like our Middle Ages analogies.

I usually describe three scale-based moats, which strengthen alongside scale:

Supply-side Economies of Scale: When a firm gains scale in industries that exhibit supply-side economies of scale, the average cost decreases as the fixed or indirect cost becomes amortized over more units. This is the most classical notion of economies of scale, exemplified by Intel, Amazon, Walmart, and Tesla. It is the hallmark of the industrial revolution; massive investment in capacity to reduce marginal cost.

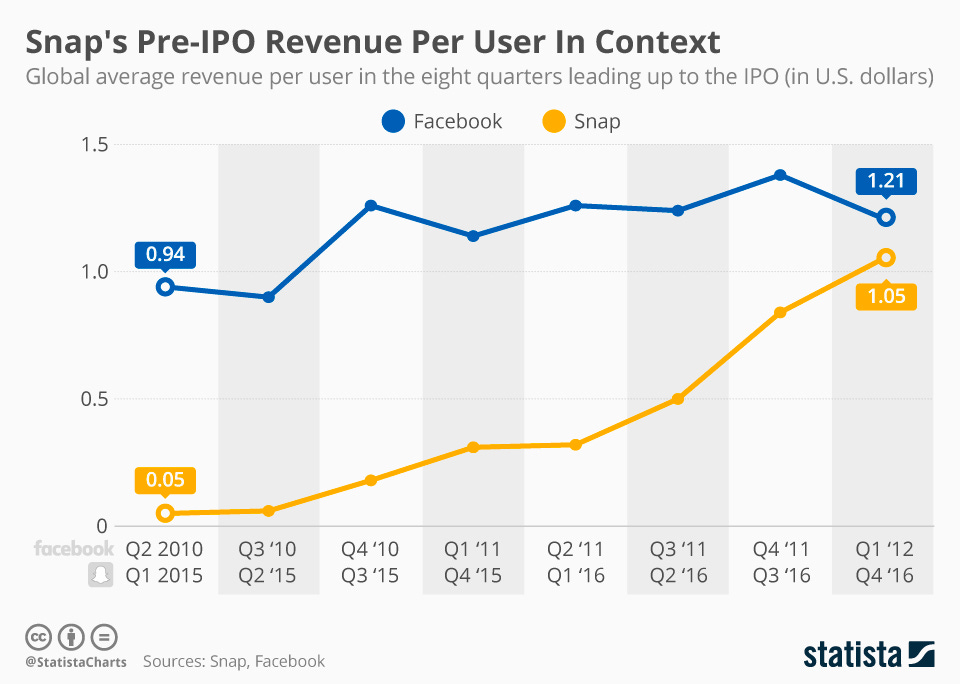

Demand-side Economies of Scale: When a firm gains scale in industries that exhibit demand-side economies of scale, the product or service value increases as value drivers on the demand side of the equation are activated. This is typical in firms that rely on network effects, such as Facebook and Snap, which create engagements between different users on the platform. In the figure below, we can see that as these firms grow their user base, the per-user revenue also rises. As more users join, willingness to pay increases (since each additional user is now connected to more users), the cost of acquiring customers decreases, and so does the churn rate.

Learning Curve: This moat includes the industries where their advantage is based on their ability to train humans or algorithms in performing a task. In such industries, firms want to gain scale since it allows them to provide a better service (or a lower-cost service) via more transactions or customers. In turn, this allows them to accelerate the rate by which the humans or the algorithms are trained. While data may not be a moat per se, data plus an algorithm can become better and further improve, with more data. This is typical in healthcare (i.e., cancer care), cyber security (the more attacks, the more you learn), and even manufacturing.

Apart from scale-based moats, there are other ways for firms to protect themselves, and it is important to note that firms can have more than one moat. And while these other moats may enjoy scale, they are not scale dependent. These include:

deep technology-based moats; either intellectual property or patents

government-based moats, and

switching cost-based moats (inertia).

All of these may drive you to accelerate your customer acquisition, but they do not depend or become better with scale. At least not significantly.

The Food Delivery Industry

So, according to my categorization, DoorDash belongs to the “demand-side economies of scale” since it is providing more value to the stakeholders on the platform rather than reducing the cost per delivery (unit cost).

And indeed, in its Form S-1, filing towards its IPO, DoorDash described its business model using the figure below:

Essentially, the firm claims to have local network effects. And indeed, one can assume that as the firm attracts more customers, restaurants will be better off. And as more restaurants and drivers (or dashers) join the platform, both customers and restaurants will be better off.

Before I get to DoorDash’s unit economics, I think it is helpful to employ the Chinese counterpart, Meituan Dianping, to understand what we may expect from a firm like DoorDash.

When Meituan went public, they released the following economic data:

So while drivers were paid less per delivery, they were delivering more orders, ultimately making more money.

As the monthly active users (MAU) increased, the total number of orders per MAU went up, And finally, the monetization rate (the platform’s rate from each order) increased from 1% to 12%, illustrating demand-side economies of scale on the restaurants side.

How did the equivalent metrics look for DoorDash towards their IPO?

More or less flat with a slight upward trend. While the number of orders increased, they generated very minimal change in the unit economics. For example, the monetization rate of DoorDash was flat for several years.

Admittedly, Meituan may have IPOed earlier than DoorDash, but at this stage, it seems that most of the scale benefits of DoorDash have been obtained. Meituan was also a monopolist for most of this time, while DoorDash came to the market when Grubhub was the incumbent and had to compete with multiple firms in each market.

Furthermore, this is an industry that is highly localized. When we talk about scale, what really matters here is local scale, or density. You still need to acquire drivers and restaurants, and advertise to local customers.

The main conclusion here is that the market is already fairly saturated in its ability to generate scale benefits in its respective industry. So “just getting more scale” was not enough of a reason to consolidate. It had to be regional and local scale.

What Does Each Side (Not) Gain?

Coming back to this deal’s main players.

Wolt: As the competition in food delivery becomes tougher, Wolt would need to continue advertising and acquiring customers as a defense against competitors. The model itself is not differentiated, so the only competitive advantage would be to keep drivers and restaurants on the platform through various promotions. We don’t have information on the firm’s finances, but it’s pretty clear it was far from being profitable. Selling to a deep-pocketed player may have been the only solution forward. It’s clear, however, that current Wolt customers are not going to be better off because of this deal.

DoorDash: First, it should be clear that none of DoorDash’s current customers (end users, dashers, or restaurants) are going to be better off, but as there was more pressure on DoorDash to grow, DoorDash had to enter markets where it could grow faster. And Wolt is active in these markets.

And while DoorDash could have tried to build the capabilities to enter these markets, it chose not to. Most likely for the same reasons that Uber decided to acquire Careem.

But it’s important to distinguish between Uber’s acquisition of Careem and DoorDash’s acquisition of Wolt. When Uber bought Careem, it was clear that Careem had a deep understanding in the Middle East that Uber just could not replicate in a reasonable amount of time.

In the case of DoorDash, there is nothing that Wolt knows about Israel (for example) that cannot be easily learned. The complexity of running this business, however, is significantly higher; the need to acquire customers (the easiest), and dashers (slightly harder), and restaurants (which may be the hardest). In other words, the complexity of the cold start problem is significantly higher in the food delivery business when compared to the ride-hailing business.

So it’s about speed.

And cash.

And local scale.

As most of these delivery platforms are not profitable, and the unit economics of the food delivery industry are very slim, we will see more consolidation, from firms trying to survive.

The main point is that, because these firms are not profitable, and need to continuously compete on all sides of the market, they need firms with deeper pockets to support them. And by support, I mean a buyout. The real scale benefits are not about becoming more efficient or providing better service to customers.

In fact, it’s not about scale benefits at all. It’s about cash and softening the competition—both on the demand and the supply side.

Again, who is not benefiting from the acquisition in the long run? Dashers, customers, and restaurants. But maybe this will create the opening for the next industry disruption, the next “Nexus Event.”