Earlier this week, the supermarket chain Albertsons and the food delivery platform DoorDash announced a new collaboration between them. As someone who studies the grocery industry as the intersection of supply chains and platforms, I find this news very exciting. The partnership has a higher degree of collaboration than usual and this tells me that more traditional firms (read, old school firms) still do not understand exactly how platforms operate and what the goals of these platforms are.

So let's start with the announcement:

"DoorDash Inc., the largest meal-delivery company in the U.S., is teaming up with Albertsons Companies to offer grocery delivery on its marketplace app in a bid to capture a share of the fast-growing sector dominated by Instacart Inc. and Walmart Inc. The partnership will enable DoorDash customers to shop across Albertsons’ nearly 2,000 stores -- including Safeway, Vons and Jewel-Osco, the companies announced Monday. Albertsons’ offerings will be available on DashPass, DoorDash’s subscription program that provides members unlimited free delivery and reduced service fees from thousands of restaurants, grocery and convenience stores."

Based on the numbers, the market believes this is a better deal for DoorDash. Its stock went up by 4.2% after the announcement, while Albertsons went up only by 1.2%, and based on Friday’s End-Of-Day share prices, DoorDash is now up ~6.6% vs. Albertsons which showed ~3.1% in increase. Clearly, the belief is that the partnership is positive for both firms, with more upside to DoorDash.

In an effort to unveil the specifics of this collaboration, I will try to explain the problem that each firm solves through this partnership and how it affects its competitive landscape.

DoorDash Continues to…Grow

In my opinion, the DoorDash side of the equation is easier to understand.

If we look at DoorDash’s financials when filing to go public, we see a typical 2021 IPO of very high revenues, but low (or shall I say, zero) profitability:

“How high-quality is DoorDash’s revenue? In the first three quarters of 2019, the company had gross margins of 39.9%, and in the same period of 2020, the figure rose to 53.1%, a huge improvement for the consumer consumable delivery confab.”

The firm is not profitable, and its losses were worse than expected during the last few months given the shortage of drivers (which we have previously discussed here). All of this is important as we realize that the firm has quarterly revenues of $1.08 billion for its first quarter of 2021 and a Trailing Twelve Month (TTM) revenue of $3.6B. For those who are not familiar with financial terms, let me provide a backdrop.

Financial analysts usually like to look at two numbers: (i) the market cap of the firm (the total number of shares times the price of the share) which is used to approximate the value of the firm, and (ii) the firm's multiple (the ratio of the market cap to its revenue) which indicates the “health” of the firm and its attractiveness to investors. The higher the multiple, the higher the future expectations for the firm. For DoorDash, the market cap is $56.18B and the multiple is around 15. Not an outrageous one, but definitely one that has a very steep revenue growth baked into it.

It is clear that DoorDash is growing fast, but the problem the firm is facing is that it already controls the restaurant market with a 45% market share. Given that this will never (and I mean never) be a winner-takes-all market, there is a limit to how much bigger DoorDash can become in this market alone (before we start seeing more cloud kitchens and new models such as on-demand food trucks). So the firm needs to grow at a very fast speed to justify its stock price. All that, while it works toward becoming profitable. At least at some point.

One of the ways in which DoorDash was trying to grow recently was through its effort to compete with GoPuff, by launching a new service: DashMart.

"In support of both of these efforts, today we’re announcing the launch of DashMart stores nationwide. DashMart is a new type of convenience store, offering both household essentials and local restaurant favorites to our customers’ doorsteps. On DashMart, you’ll find thousands of convenience, grocery, and restaurant items, from ice cream and chips, to cough medicine and dog food, to spice rubs and packaged desserts from the local restaurants you love on DoorDash. DashMart stores are owned, operated, and curated by DoorDash."

What does this service lack? The main value proposition of DoorDash’s restaurant delivery is speed and variety. DashMart is fast but has a very small product range, so it doesn’t deliver a consistent value proposition.

What does Albertsons have that DoorDash doesn't? A huge variety located close to customers and a customer base that is looking (at least partially) for the convenience DoorDash offers.

So, what does DoorDash get from this partnership? It achieves growth with relatively low new costs, which allows it to improve its value proposition when competing with its more traditional competitors like Uber and GoPuff. It also allows it to start competing with Amazon and Instacart, by potentially offering faster deliveries.

As a platform, DoorDash will never refuse more engagements happening on its platform. Never! The fact that it has various collaborations with several convenience chains is already very telling here.

Albertsons Gets What it Desperately Needs

We must keep in mind that Albertsons is a traditional supermarket chain. High in revenues and, as I will explain below, low in stock multiple. It is a bastion of the past, looking for a place to grow but with little growth prospects through its traditional channel.

Indeed, the company’s revenues are at $69.69B, but its market cap is at $9.368B. I don’t think it is necessary to compute the multiple here to understand that the market is not viewing Albertsons’ future favorably. And just to complete the picture, the firm has excellent gross margins (approx. 29.9%), but minuscule net margins (approx. 1.22%).

Suppose you are wondering whether this is specific to Albertsons or whether other supermarket chains show similar economics. In that case, we can compare it to Ahold Delhaize which shows the following figures: Market Cap: $30.992B, Revenues: $85.364B, Gross Margin: 27.6, and Net Margin: 1.77. In other words, Albertsons has worse economics than AHold, but not by much. Given the low margins and the low growth of the market overall, the multiples are not surprising.

Taking a look at how the grocery industry is shifting, we can see Amazon getting deeper into this market with faster delivery and a massive investment in the last mile (following their acquisition of WholeFoods), and Instacart delivering from almost every supermarket.

So, traditional supermarkets are starting to see the market they controlled for half a century changing and they need to react by offering more convenience.

For many years, these traditional firms had one main advantage: their distribution. They had expensive locations, ample real estate, and robust distribution systems which allowed them to bring products to their customers. Customers came since they were the only place to find these products. Over the years, the supermarket chains offered an increased variety with some level of inconvenience that people got used to.

They were the old school platform, the “meeting place” between consumers and brands. They maintained low margins but had huge volumes to compensate for them.

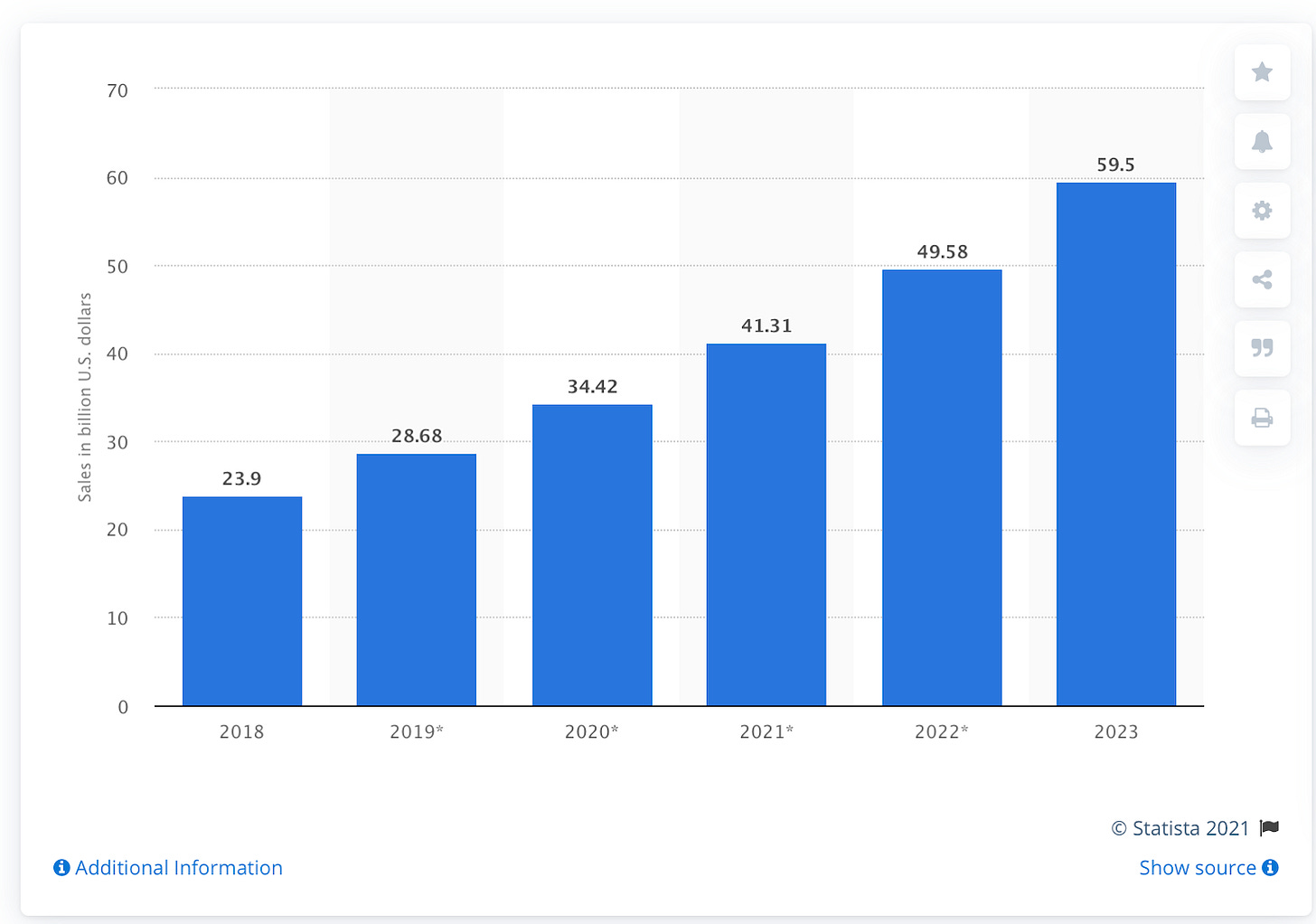

With the change in technology, location is no longer a sufficient competitive advantage (or at least not as big as it was), and one can order from different stores, finding the ones that carry the product they truly want. As we discussed before, this shift from the traditional grocery model to the online grocery is lagging compared to other areas of e-commerce, but the change is bound to happen (see the graph below for “Online grocery shopping sales in the United States from 2018 to 2023”). This change was accelerated by COVID and with the emergence of Millenials and Gen-Zs, as the primary shoppers, we will see it happen faster.

As I have written before, the end game is clear. We will, at some point, be ordering most of our groceries online.

The question is, what's going to happen to traditional supermarket chains, like Albertsons until then? And what are the risks that each firm is taking, and in particular Albertsons, by entering into this partnership? What does Albertsons really stand to gain?

Marginal Thinking

This is where marginal thinking is a mistake. Marginal thinking is the idea that for both firms, the next step makes sense in the short run, but in reality and long term, it only makes sense for one of them.

If you are a supermarket chain and you know that, in the future, you will have no advantage if you get stuck in the middle of the value chain, why would you outsource this core competency?

This is precisely what Albertsons is doing. Rather than developing the capabilities to be a new-age grocer (both online and brick-and-mortar), firms choose to work with different platforms (such as Instacart and DoorDash) and let them build this channel for them, essentially allowing them (the platforms) to collect data and learn how to best operate, while also keeping their margins high since they don’t bear the cost of real estate or inventory.

This is very much related to the Shih Smiling Curve, only applied to the food supply chain. For many years, the supermarket chains held the right-hand side of this curve, managing the relationship with the customer. When Albertsons allows its customers to go to Instacart and DoorDash, it essentially cedes that side of the curve, while differentiated brands hold the other side. The middle gets squeezed, which translates into lower margins.

I call this ‘marginal thinking’ because it only seems to be the right decision in the short term. Since developing these capabilities will be costly, for a traditional firm such as Albertsons, partnering with DoorDash, will lead to incremental revenues with little additional cost. We have seen the struggles Walmart has had in developing similar e-commerce capabilities, but not creating them is very shortsighted.

Over the years, AHold has taken a different approach. It bought Peapod, one of the early e-grocers, and FreshDirect, one of the original and leading players in the New York market. Peapod was recently relegated to being a lab for retail development, but the idea is clear: AHold believes that it needs to own this capability. Several years ago Albertsons acquired Plated, one of the main players in the meal-kit sector, so M&A is clearly a path the firm has considered but has chosen not to take. At this stage, given their market caps, DoorDash is more likely to buy Albertsons out rather than the other way around.

If you think that I am being too critical of Albertsons, let’s look at a very different market, which has been disrupted by platforms. The movie and TV market. When Netflix entered the market, studios were happy to collaborate and offer their “back of the catalog” movies and TV series since they couldn’t show these anyway. Once Netflix became too big, most of the studios realized what Disney realized early on. Platforms do not allow you to be differentiated. If they allow for differentiation of the “sellers” or “producers” on the platform, they cannot extract the margins to justify their unit economics.

Disney realized it and built Disney+ while removing all of its content from Netflix. The main advantage that Disney had was that it maintained a strong brand name. Albertsons doesn't.

I understand that talent is hard to get and that building these capabilities is difficult, but outsourcing them to a savvy platform is just a dire mistake with long-term implications. Outsourcing the innovative part of your industry to a fast collaborator that will soon turn into a competitor is something that just does not make much sense to me.

If you are wondering why the market rewards Albertsons after all this analysis, it is because first, the market has traditionally rewarded “cleaner” balance sheets. The market likes firms that reduce their asset-liability and in this case, developing these e-commerce capabilities will require massive investments. Boeing has gone down this path of selling and outsourcing important components, only to reacquire them years later. A second possible reason for the market’s reaction is that, over the years, the stock market has shown a bias towards short-term outcomes over long-term capabilities. This partnership is clearly beneficial in the short term, but its long-term implications are hard to assess, financially.

Note that this partnership has (almost) nothing to do with Covid, yet it exposes what we have seen again and again with every supply chain shortage during this pandemic: The preference for short-term financial outcomes over long-term capabilities has horrendous consequences to firms and the industry.

Great Article, Gad. I agree with your assessment, but in a short term, I don’t think Albertsons has many options to be relevant in e-commerce. Hopefully, they are using this time to build this long term capability.

Another nice blog, Gad. This sounds much like the Toys R Us and Amazon partnership, and we all knew what happened to Toys R Us!