Every so often, I stumble upon a news tidbit that shakes the very core of my existence as an Operations professor, thus compelling me to pen an article while fully aware that for the majority of my readers, it may seem as nothing more than a humdrum proclamation.

This week, FedEx announced its decision to merge its operations under one roof, and this is a major event:

“‘We will be consolidating our operating companies into one unified organization,’ FedEx CEO Raj Subramaniam told investors Wednesday. It’s something many analysts and investors have been wanting to hear for years, as the company’s devotion to separate Ground and Express service lead to clearly visible displays of inefficiency — not to mention flagging financial results.”

The reasoning, as described by FedEx’s leadership:

“‘If you’ve ever seen a Ground and an Express truck in your neighborhood on the same day or watched them pass each other on the street, then you know what we’re trying to accomplish,’ John Smith (no relation to founder Fred Smith), who will head the combined entity and report directly to Subramaniam come April 16, said at the presentation.”

As coined by executives, the newly dubbed “One FedEx” initiative will prioritize more cost-effective ground transportation whenever feasible, even for Express parcels that have typically been transported via air. International packages will transition from multiple flights to a single flight covering the longest leg of the journey, with truck or van trips at both ends.

The transformation will align FedEx’s operational strategies with competitors like UPS and DHL, moving away from the hub-and-spoke model that Fred Smith popularized and made the Memphis hub famous.

For years, the courier has maintained separate express and ground package services. The latter, which was acquired in 1998, relied on third-party contractors for its last-mile parcel delivery, but effective June 2024, it will become “a single entity operating a cohesive, fully integrated air-ground network under the esteemed FedEx brand.”

This is the end of an era and raises so many questions: Why? Why now? Why is this the end of an era? What’s the potential downside?

Operational Focus

One of the primary benefits of a more compartmentalized approach is focus.

But what exactly does focus entail?

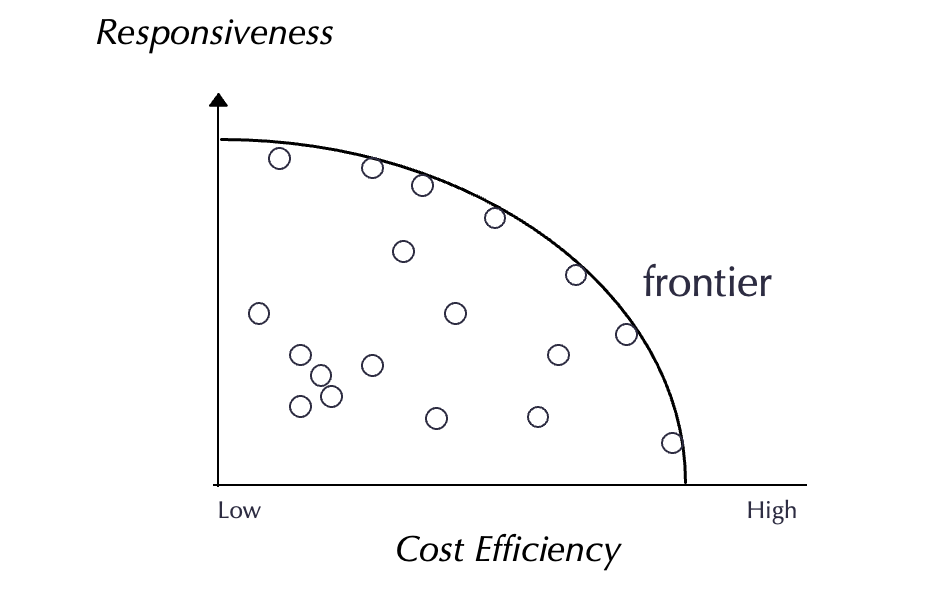

To appreciate the challenges FedEx is currently facing, it’s crucial to understand the main idea behind their previous strategy, which epitomizes what we often refer to as “focus.” In the context of operational or strategic focus, this means concentrating on a particular aspect of the operational frontier.

Let's pause for a moment and explain what we mean by "frontier."

The term suggests that at any given time, and considering the available technology, companies are positioned on a spectrum based on their specialization (strategic position). Firms also have varying aspects on which they focus (operational processes). In the delivery sector, for example, some firms are cost-driven, while others prioritize speed. Being on the frontier requires a strong alignment between operational processes and strategic positions. The main driver behind the need for “alignment” is that no process excels in all dimensions. There are always tradeoffs, and in delivery services, it is challenging to develop processes that minimize costs and maximize responsiveness and reliability simultaneously.

Why is this so?

The answer lies in the need to make difficult decisions, such as determining the right network structure. A hub-and-spoke system works well when the goal is speed and reliability but is quite wasteful in terms of costs and milage per package. This also applies when considering which modality to use (e.g., a truck is cheaper than a plane, but slower), and when deciding the appropriate metrics to incentivize employees. For example, if the “north star” is a cost or truck utilization, employees on the ground (no pun intended) will make decisions that may result in low costs (as expected), but may also increase the likelihood that packages won’t arrive on time.

The reality is that to be on the frontier, a company must achieve alignment; otherwise, firms with better processes that yield superior outcomes can overtake them.

FedEx followed this approach for many years operating separate businesses for its fast and efficient services. This made management more straightforward, as each service could continuously optimize for its respective goals, including infrastructure investments, hiring, and compensation. Everything was fine-tuned toward maximum performance for each market segment.

However, the main problem with the “focused” approach is its inefficiency. In terms of overall resource allocation, there is significant redundancy between the two services.

FedEx is now recognizing this limitation and is adapting its strategy accordingly.

Why Now?

To understand the need to change, we have to better understand the benefits of the integrated system and when these benefits are less significant.

For many years, FedEx maintained as much of a focused approach as possible, raising the question of whether operational efficiency or incentives and structure drive overall performance. The current shift suggests that the industry may have reached a point where aligning incentives and simplifying the system is no longer sufficient to reap further benefits, and it's necessary to build structural efficiencies instead.

Jan Van Mieghem (a co-author and long-time collaborator) and Baris Ata sought to determine in their research paper The Value of Partial Resource Pooling: Should a Service Network Be Integrated or Product-Focused? when an integrated network is preferable to a dedicated one. Their findings offer valuable insights:

“We investigate how network design impacts capacity requirements and responsiveness, which is a natural performance indicator of quality of service. Inspired by the contrasting network design approaches of FedEx and UPS, we study when two service classes (e.g., express or regular) should be served by dedicated resources (e.g., air or ground) or by an integrated network… Our results suggests that operating dedicated networks is a fine strategy (meaning that network integration is of little value) if the firm primarily serves express requests with high reliability and if the correlation with regular requests is not strongly negative.”

To understand why this isn’t trivial, let’s look at the following figure:

It should be obvious, from an operational point of view, that networks with an additional arrow allowing regular packages to use the capacity of the fast and flexible solution should be superior. And indeed they are. But this doesn’t offset the managerial difficulties that these systems pose in terms of incentives and overall simplicity. So, Van Mieghem and Ata aim to show that these two networks are equally good under certain conditions. Then they show that the dedicated network, the type FedEx has been operating until now, is almost as good operationally (and better overall, given its simplicity) if:

(1) the firm primarily serves express requests with high reliability, and

(2) the correlation with regular requests is not strongly negative.

The first one is clear. If demand and the willingness to pay are high for a reliable service, then a firm wouldn’t lose much by having two dedicated systems (and would most likely benefit from the simplicity and incentive alignment in running it).

Did this change over the last few years?

I would argue that FedEx was a great service for B2B when documents needed to be shipped. Unfortunately for FedEx, in the world of DocuSign, documents no longer need to be shipped. Most shipping now concerns end-customers, where expectations are still of high convenience, but there’s no longer a high willingness to pay, and time matters less. And indeed:

“A surge in e-commerce shipments in recent years and higher costs associated with delivering packages to homes pushed the company to bring the operations closer together to avoid duplication. Previously, FedEx has dispatched Express and Ground trucks to move packages in the same neighborhoods, sometimes creating confusion for customers and extra costs for itself.”

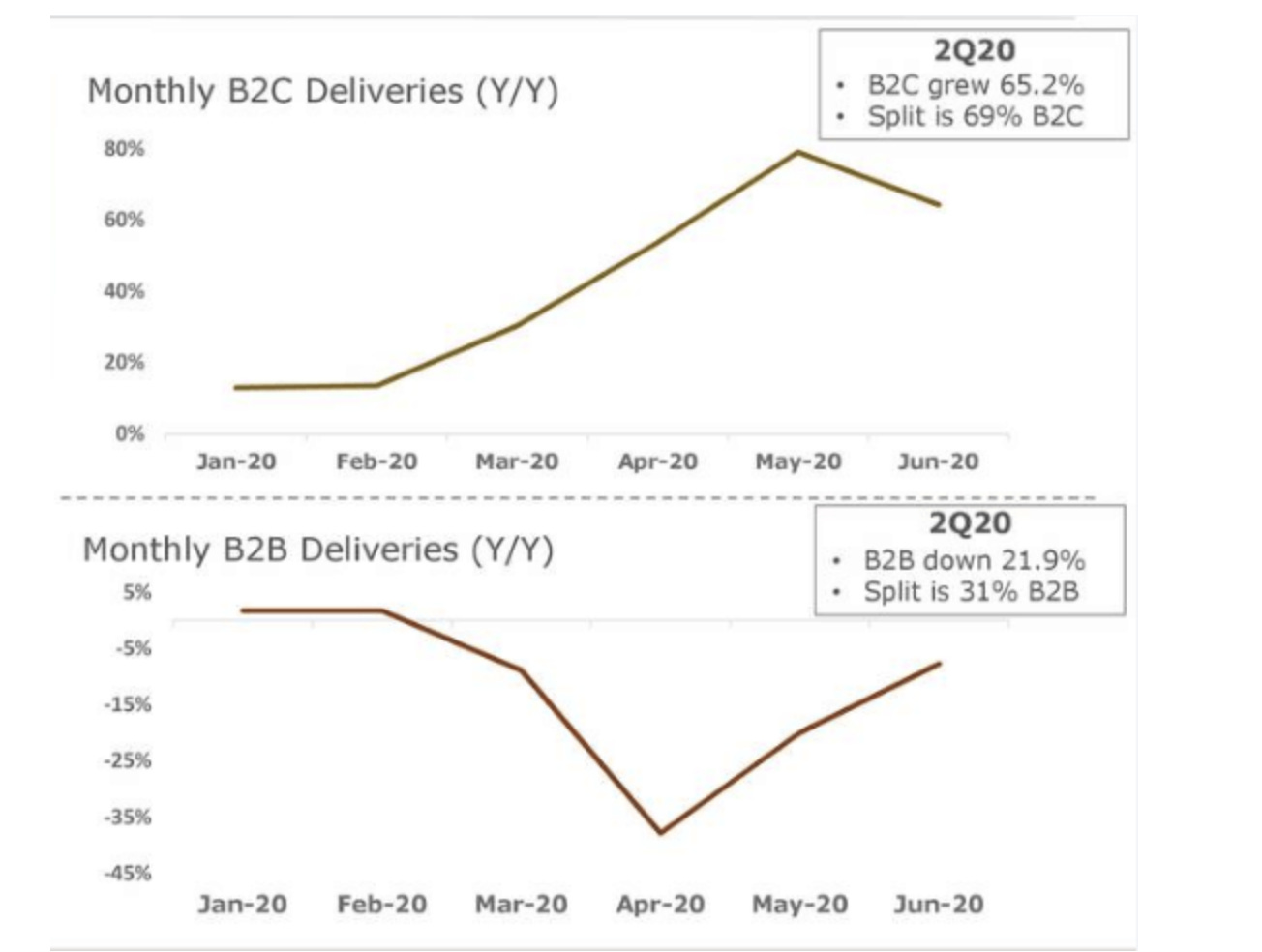

The second condition where a fully connected network might be better is if there is a negative correlation between the type of services (or any demand streams for the different models). If demand is negatively correlated, then a pooled system is preferable.

Did this change?

Looking at the demand pattern, it seems that B2C and B2B are negatively correlated. One would assume that B2C has a preference to cost and B2B for speed (as discussed above):

What’s the implication for firms?

“Focus” works well early on (when there are limited resources) and when speed (or quality) is valued enough to separate complexity (speed) from simplicity (cost). But when times are hard, it’s more difficult to justify it.

What’s the Risk?

An interesting aspect is that FedEx is not only adding an “arrow” that allows the use of expensive resources to ship cost-efficiently, but they also claim to be adding an “arrow” where “express” customers can use the slow capacity service, which is alarming. The impact, of course, will be felt:

“In a research note, Morgan Stanley’s Ravi Shanker also questioned whether FedEx would be able to reroute parcels from express air to truck and utilize noncentral air hubs without diminishing service levels. Parcels ‘will make many more stops and have many more touches in the new system than today, which is demonstrably more expensive and has the potential for disruption,’ he said. And more outsourcing reduces FedEx’s direct control of network operations, which could increase quality problems during peak season or periods of tight capacity.”

There are many risks to implementing such a change, from the difficulty to integrate, to the lost accountability and focus on regulatory risks.

But there is another lesson to be learned here.

FedEx was one of the most admired firms for its operational excellence even though it was dropped by Amazon and it struggled while competing with UPS.

And this is related to how successful the “dedicated” system was. It was due to this success that FedEx found it difficult to let go.

The point is that the more optimized the firm, the harder it is to make these changes and admit that the old system no longer works with the new customer demands and behaviors.

Operations strategy is about the constant reconciliation of market preferences and operational capabilities.

And that’s hard.

Great points! I think similar problem exists in software product development companies - a tension between fully autonomous teams vs a shared resource pool.

As for FedEx, as a consumer, I do not see any difference between FedEx and UPS anymore. They seem to offer same services and at relatively similar prices. There is still little more brand reliability premium I attach to FedEx but that has been declining for me.

Also, overnight document delivery has been gone for almost a decade now. Why did it take that long for FedEx to retool it's operations?

I also wonder last-mile drone delivery is reaching a high enough level of maturity where it influences FedEx's medium-term strategy. It is probably better to have the Ground and Express combined before adding drone capabilities.