You may have heard that In-N-Out Burger is expanding eastward. This is a big announcement for a chain known for its reluctance to move beyond California (and then Nevada, and then Texas).

How big?

“The decision to open a Franklin, Tennessee territory office, which will oversee the chain’s eastward expansion, is especially surprising considering that, in 2018, In-N-Out CEO Lynsi Snyder, the granddaughter of founder Harry Snyder, told Forbes that the chain would not expand east of Texas as long as she was alive. ‘I like that we’re sought after when someone’s coming into town. I like that we’re unique,’ Snyder said at the time. ‘That we’re not on every corner. You put us in every state and it takes away some of its luster.’”

Not big enough?

Not only did the firm announce the expansion, but the governor even joined in with a statement:

“‘I’m proud to welcome In-N-Out Burger, an iconic American brand, to the Volunteer State,’ Gov. Bill Lee said in a statement. ‘Tennessee’s unmatched business climate, skilled workforce and central location make our state the ideal place for this family-run company to establish its first eastern United States hub.’”

Reading this, you’d think Tennessee just got to host the new headquarters of OpenAI, but no… It’s a burger chain.

A chain of “run of the mill” burgers.

(I may have just lost all my California readers).

Well, I didn’t grow up in the US, so I never really understood the hype. The burgers are good, but nothing to write home about.

Did I try them on one of my visits to California and order from the “secret menu”? Sure.

Was it fun and efficient? Yes.

Will I go out of my way to order them again? Not so sure.

But again, I’m not a food critic, merely an operational one.

And from an operational and scale-wise perspective, In-N-Out is an interesting story.

Burgers are a Hard Business

Using Porter’s five forces legendary model, one realizes that burger restaurants are a terrible industry to enter. For starters, suppliers (e.g., beverages, meat, and condiments) all have high bargaining power. On the other hand, entering the market is easy, customers have plenty of other alternatives, and margins are not great. So if someone were to ask me whether to start a new chain, I would advise against it.

But In-N-Out is doing really well. It’s a family-owned business, so there is no stock performance to show, but the founder’s granddaughter, Lynsi Snyder, who is the sole owner, is worth $4.2B. According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, in 2012 she was the youngest American female billionaire.

But more than that: the chain has a huge following.

I usually look at how many people have a tattoo with chain-related graphics as a sign of fandom:

I’m not sure how many would go for a Toyota tattoo.

(By the way, the firm won’t hire people with visible tattoos as part of their dress code).

The reason for such a strong following is not clear, but factors such as staying west and away from corporate pressure, and its secret menu, have all contributed. For many of my California friends, In-N-Out is a must when returning home.

This loyalty has clear financial implications. Based on some estimates (since the firm is private), an In-N-Out store brings in approximately $4.5 million in gross annual sales (almost twice the amount a typical McDonald’s grosses —$2.6 million).

The same article estimates In-N-Out’s profit margin in 2018 at 20%. At the time, Shake Shack had 16% and Chipotle 10.5% (note that Shake Shack’s margins have improved since, but I don’t have the data to compare with the current margins).

So how does In-N-Out maintain its margins?

First: operational excellence rooted in its limited menu. A limited menu means reduced costs in raw ingredients (better bargaining power, less waste). The company saves money by processing beef in-house and by avoiding expensive urban areas (reduced real estate costs) for it’s store location —keeping a single location within city limits in LA and SF. Avoiding cities and clustering locations close to highways also reduces transportation costs.

This allows the firm to keep its prices low:

“Over the past 30 years, the price of the Double-Double hasn’t even kept up with inflation. In 1989 the sandwich cost $2.15, or about $4.40 in current dollars. It costs $3.85 today. A combo meal (Double-Double, fries, drink) goes for $7.30, compared with $10.94 for Shake Shack’s standard double-burger patty and fries.”

But operational excellence is only part of the story (and the one easy to replicate in this case).

A bigger part is the operational approach and how it is propagated.

The “Catholic” Approach to Burger Making

The chain is known for its religious roots (e.g., bible verse numbers on their wrappers and cups), but this isn’t what I mean.

A critical questions in scaling is whether a firm will follow a Catholic or a Buddhist approach to operations —terms that were introduced by Sutton and Rao in their book, Scaling Up Excellence: Getting to More Without Settling for Less.

The debate can be summarized as follows:

Catholicism – the aim is to replicate preordained design beliefs and practices.

Buddhism – an underlying mindset guides people’s actions, but the specifics may vary among people and locations.

The reality is that balancing the need to replicate tried-and-true methods and the need to adapt those methods (or create new ones) to suit local circumstances, is difficult. This tension determines whether a firm will succeed or fail.

In-N-Out is considered a success story of the Catholic approach, but the reality is that in most cases, this approach fails.

In their book, Sutton and Rao discuss Home Depot’s “catholic plan” to replicate their DIY model in Chinese markets, not realizing that China doesn’t have a DIY culture. The results were terrible. IKEA took a more adaptive approach with better results.

But what does Catholicism entail for In-N-Out?

“In-N-Out is a culinary anachronism. It hasn’t evolved much since Snyder’s grandparents founded it in 1948. Buns are baked with slow-rising dough each morning. Three central facilities grind all the (never-frozen) meat, delivering daily to the 333 restaurants. Nearly all its locations are in California, and all are company owned. (In-N-Out does not franchise.) Heat lamps, microwaves and freezers are banned from the premises. The recipes for its burgers and fries have remained essentially the same for 70 years.”

From the beginning, the company’s founders were determined to control as many facets of the operation as possible. They employed their own construction crew to build new storefronts, processed their own meat, and established a wholesale business to stock up on office supplies. When the founder died in 1976, In-N-Out had 18 outlets —all in California.

Of course, this approach doesn’t just apply to operations. The entire look and feel is consistent throughout. The red-and-white color scheme, the chrome tables and vinyl chairs, and the palm trees printed on the company’s plates and painted onto the restaurant walls are all identical to the original stores. Nothing has changed.

Even the secret menu is standardized:

“Ok, you’ve heard the rumors, wondered what was on it, maybe even felt a little left out of the loop. But in reality, we don’t have any secrets at all. It’s just the way some of our customers like their burgers prepared, and we’re all about making our customers happy. So here are some of the most popular items on our not-so-secret menu.”

So, yes, making the customer happy is important, but you need to “know” what’s on the secret menu, and this knowledge is part of the magic.

Scaling a Religion

The approach sounds great, so why do I anticipate challenges with its future scaling?

I see multiple pressure points on the firm’s operating system:

The first challenges start when scaling to different regions, where customer preferences may vary. Just like IKEA, McDonald’s faced similar issues when it expanded to new countries with different attitudes toward beef. However, I don’t expect this to be an issue for burgers in the US. Once you sampled Texas and California (California’s a big state with some areas resembling Alabama and others NY), I don’t think you’ll encounter a very different set of customers in terms of their palates. This would look different if In-N-Out expanded to France or India.

The second challenge comes from the supply chain. It’s easier to be Catholic if you have a church nearby. In-N-Out is its own supply chain since the firm does everything internally (they even make their own beef patties), and in order to do so, while maintaining the necessary freshness requirements, they must be close to their operating centers. This slows down growth, as it has done until now.

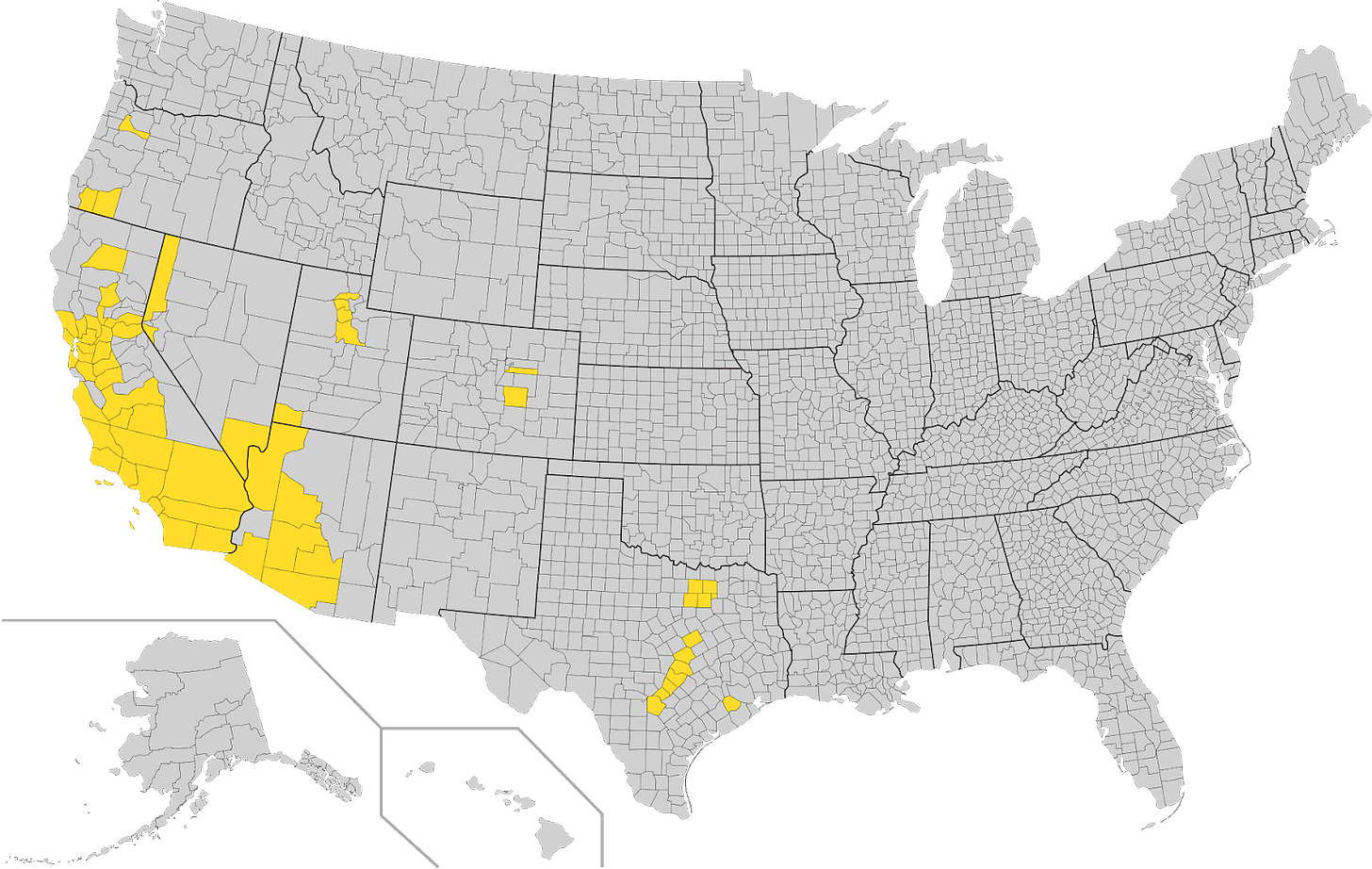

Building a second distribution center was the key to expanding to Texas:

Comparing the two images above (the map with the distribution centers and the one with the store layout in 2020, before the upcoming expansion), it’s evident that the Tennesse expansion is the limit of the Texas distribution center. To expand further east, the firm will have to build a new center.

If you're wondering why the distance is 685 miles, the company previously stated that it only allows new locations to open within a 500-mile radius from their distribution centers. However, the Baldwin Park, CA facility supplies a branch all the way out in Centerville, Utah, which is 685 miles away.

But I think there is one more pressure point: Competition.

As a firm grows, competition shapes its decisions more than in the beginning.

Being present only in California and Texas, the cmpany encounters a limited set of competitors. Sure, McDonald’s and Burger King are everywhere, but Shake Shack (In-N-Out’s true competitor) has limited presence in the West Coast.

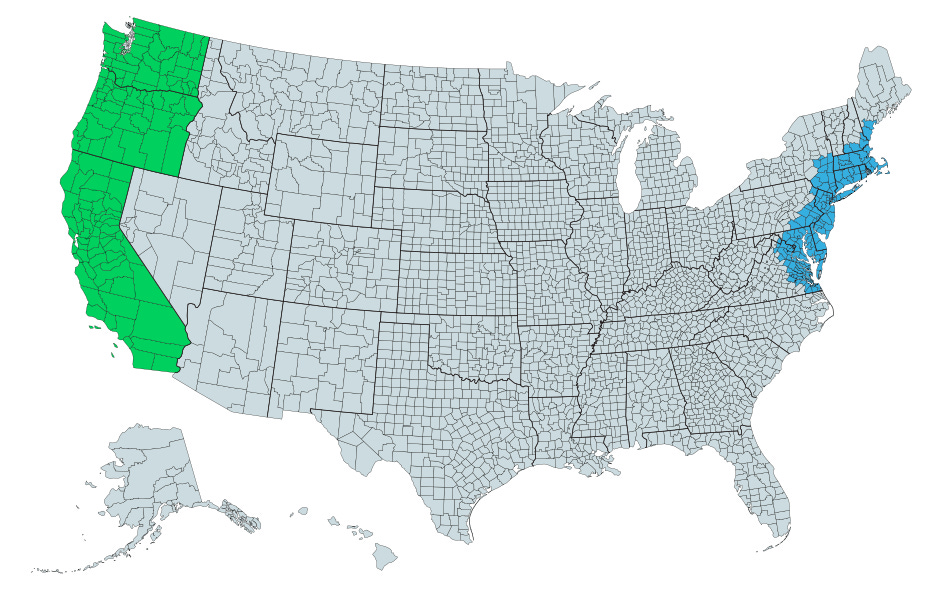

If In-N-Out is planning to come to New York and Pennsylvania, it will have to tweak its menu (maybe add slightly healthier options), and offer faster service (it’s not that fast to be honest). In other words, I expect it to re-shape its menu, and when the menu starts to change, so does the approach to operations. Even the approach to store location will be limited. In the following map, which shows two areas with the same population, it is clear that the East Coast is more dense:

Anything can happen, and it’s possible that the chain will decide not to change or grow. But that would be proof that its operating model has been limiting its growth. While this is something I absolutely respect, it’s hard to justify it in a world where a firm’s valuation is tied to its growth potential, as much as its margins.

The business is currently family-owned, so a valuation is not yet a concern, but if and when the firm becomes public, slow growth may be harder to justify.

I wonder if catholic model even work in country like India, where preferences change every 50 miles.

Good analysis of a bold and risky move for a traditionally conservative operation like In-N-Out Burger. It's a quintessentially California brand that might still appeal to consumers in other states, especially if it keeps its super-simple menu, fresh ingredients, and affordable prices. I was thrilled to discover In-N-Out when we lived in Arizona, and it's the first place I visit on every trip back. The fresh burgers and fries really do taste better than the other big chains, and the prices and simplicity beat Shake Shack, in my opinion. If they can succeed in Texas while going head-to-head with local favorites like Whataburger, they can also succeed in other competitive markets. In Tennessee, they'll meet up with Hardee's/Carl's Jr., plus other regional favorites. In-N-Out also won't have the name recognition they enjoy out West, so it will be interesting to see if they invest in advertising or marketing promotions, which they typically don't need in their familiar home markets, and which would add to their costs.