India’s Operations Revolution: Lessons from Zepto, Rebel Foods, and the Dabbawalas

This Week’s Focus: Lessons in Efficiency and Innovation

Following a 10-day visit to Bangalore and Mumbai with my program’s students, I witnessed firsthand how India’s food industry has mastered the art of balancing market needs with operational capabilities. Zepto’s speedy deliveries, Rebel Foods’ tech-driven cloud kitchens, and the Dabbawalas’ 130-year tradition of reliability all highlight unique approaches to providing fast, affordable, and dependable food service while staying efficient and sustainable. This week we explore their stories, which offer valuable insights for businesses aiming to navigate the complexities of modern markets while staying adaptable and customer focused

After a 10-day long class visit to Bangalore and Mumbai with 20 students from my program, I have much to write about this transformative (not a hyperbole) trip meeting amazing firms and entrepreneurs.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be sharing more, but today, I want to focus on one recurring theme: food.

Cheap, fast, and reliable food is an operational necessity in India. From Sequoia-funded hyper-efficient food delivery startups like Zepto and Rebel Food’s tech-driven cloud kitchens, to the enduring legacy of Mumbai’s 130-year-old Dabbawala network, India’s food industry’s key players have not only mastered cost efficiency and speed but have also adapted to evolving market needs.

Let’s dig deeper.

Zepto: The 10-Minute Delivery Phenomenon

Zepto, the Indian quick-commerce startup, has redefined urban grocery delivery with its bold “10-minute promise.”

Founded by Aadit Palicha and Kaivalya Vohra (whom we met on the trip), Zepto operates in a hyper-competitive market where firms like Zomato, and Blinkit pre-existed and Kirana stores—small, family-owned shops that sell groceries and other sundries—can be found at every corner throughout the country.

Initially, Zepto tried developing a software to help Kirana stores offer delivery and pickup services. But when that failed, the firm began carrying its own inventory, and doubled down on the delivery time.

The promise of delivering groceries within 10 minutes is more than a marketing gimmick. In our conversations, the founders mentioned that while it wasn’t their initial goal, they observed consumer behavior and noticed that customers who received products fast would order more frequently and in larger quantities.

People often ask me whether a “10 minute delivery” is really necessary, and the answer is “No, it isn’t.” But in a world with so many different store options, for consumers to change their behavior, the delivery model must deal with the inconvenience of waiting for an order. Whether the acceptable waiting time is 10, 15, or 30 minutes is a different question. At least in India, the answer seems to be 10.

The key to Zepto’s success lies in its network of “dark stores,” small warehouses strategically located in densely populated urban areas. These stores house a limited selection of high-demand products and are positioned within a 2-3 kilometer radius of customers. This proximity allows for rapid deliveries, while the operational model ensures efficiency at every stage.

Picking items takes an average of 90 seconds (yes, you read it correctly), thanks to the streamlined layouts and curated product assortments tailored to customer preferences. I didn’t believe it was possible (you know how skeptical I am), so I asked to follow the pickers. They ran so quickly between the aisles that I’d lose them every time. But 90 seconds is pretty accurate.

Despite the efficiency, the economics of ultra-fast deliveries remain challenging. The average order value (AOV) is around $5, while labor costs (including picking and delivery) are about 50 cents, they do aggregate, particularly for groceries where margins are narrow to begin with. Zepto mitigates these costs through high order densities and quick turnaround times, making the unit economics work even in a low-margin environment.

The excess labor capacity in the stores and the number of drivers—referred to as Zeptons by the firm—is astonishing, and such a system can only be sustained in a country like India where there’s a huge gap between customers who are willing to pay for speed (even if there aren’t many), and an ample supply of cheap labor. So it’s pretty clear why 10-minute deliveries aren’t feasible in the U.S.

But the firm is not profitable even at the dark store level.

To build a sustainable business, Zepto has moved beyond traditional delivery revenue, and leverages its app as an advertising platform, similar to Instacart, allowing brands to pay for premium visibility. This additional income supplements the slim margins from their grocery sales.

Another promising revenue stream is Zepto Café, the company’s foray into cloud kitchens (more on this in the following section). By offering ready-to-eat meals alongside groceries, Zepto taps into higher-margin categories. Cloud kitchens reduce overhead costs associated with dine-in establishments, enabling Zepto to control production costs while increasing average order values. The initiative reflects Zepto’s broader strategy of vertical integration, leveraging its existing infrastructure for new revenue opportunities.

When Zepto first announced its 10-minute delivery model, many doubted its feasibility in India’s chaotic urban landscapes. Yet, predictive demand algorithms, optimized dark store locations, and streamlined operations have allowed Zepto to deliver on its ambitious promise (no pun). It was quite interesting to observe the hand-offs between the pickers and the drivers, done in a way that avoided mistakes and any hold-ups.

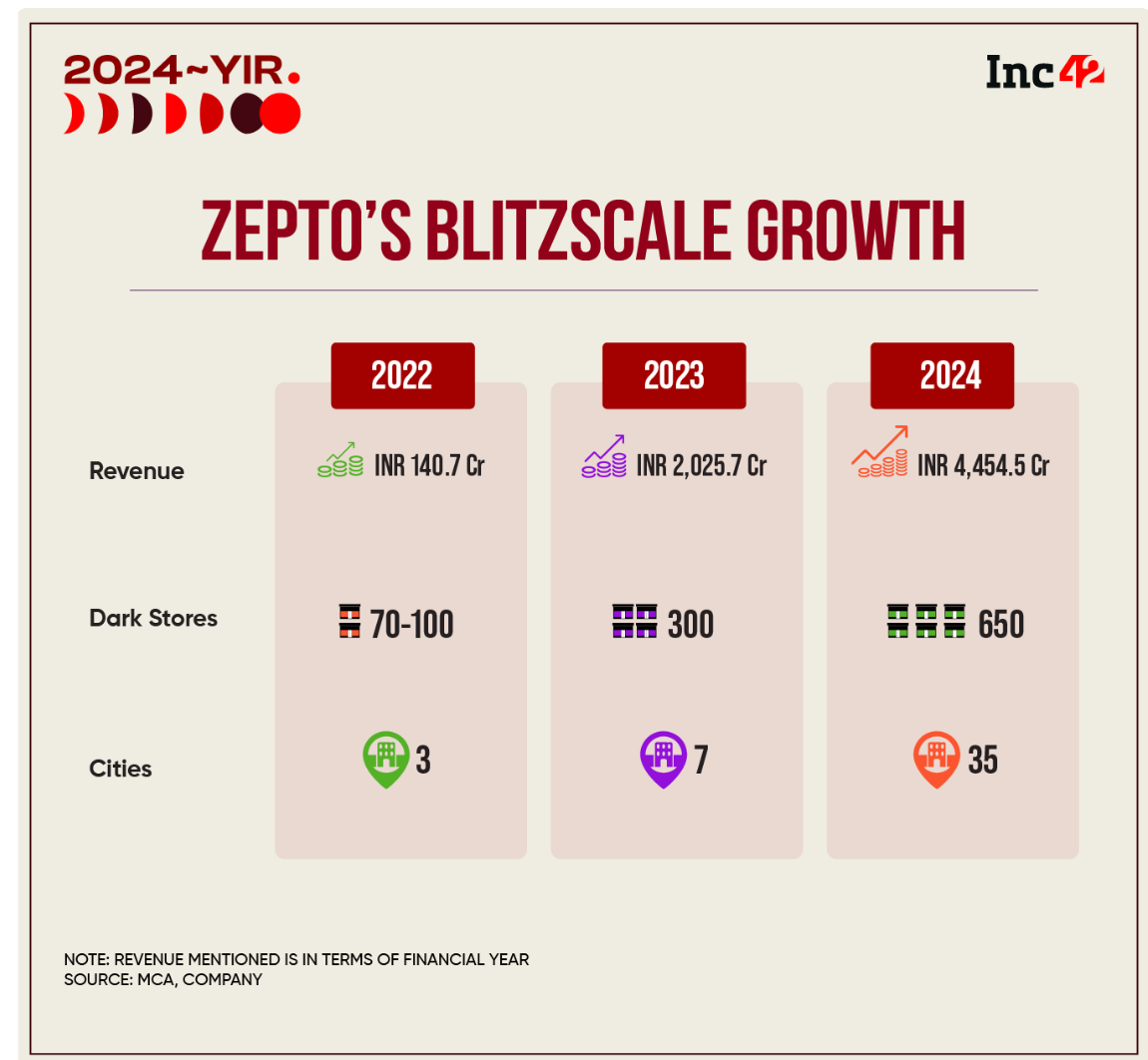

The company’s growth trajectory has been impressive. Since its inception in 2021, Zepto has expanded from a few cities to over 35 urban centers, doubling its dark store network and tripling its workforce by 2024. This rapid scaling reflects not only the market potential, but also Zepto’s focus on capturing early mover advantages in the nascent quick-commerce segment.

As Zepto continues to grow, several challenges remain. Maintaining cost efficiency without compromising service quality is an ongoing concern, especially as competition from giants like Swiggy and Amazon intensifies. Scaling Zepto Café while keeping its core grocery business robust will require careful resource allocation and strategic planning.

During our visit at the dark store, the average time from order to delivery was 17 minutes. Not bad, but not 10 minutes. I’m guessing that orders through Zepto Café have a higher margin but can’t meet the 10 minute promise.

Zepto’s journey epitomizes the rapid evolution of urban commerce in India. The 10-minute promise is more than a convenience; it’s a statement of operational ingenuity and customer-centric innovation. However, as the quick-commerce market matures and labor costs increase, Zepto’s ability to adapt and innovate will determine whether it can sustain its early success and continue to redefine the industry.

Rebel Foods: A Revolutionary Journey in Cloud Kitchens

We also had the opportunity to meet and visit Rebel Foods, which specializes in the cloud kitchen market.

Rebel Foods, originally known as Faasos, began in 2004 as a single QSR (Quick Service Restaurant) outlet in Pune, India. Founded by Jaydeep Barman and Kallol Banerjee, the company initially aimed to serve wraps in a fast-casual format. However, scaling physical restaurant locations is capital-intensive and operationally challenging, so in 2015, faced with high real estate costs and intense competition, the founders pivoted, transitioning from a traditional restaurant model to a delivery-only cloud kitchen concept.

This shift marked the birth of Rebel Foods, with a vision to create a global network of virtual brands operating out of shared infrastructure. Today, Rebel Foods operates over 450 cloud kitchens across multiple countries and is the world’s largest operator of its kind.

A defining feature of Rebel Foods is its multi-brand strategy, which emerged as a solution to the limitations of a single-brand kitchen. Each Rebel kitchen functions as a production hub for several distinct brands, catering to different cuisines, price points, and customer demographics. This model allows Rebel to maximize kitchen utilization and target multiple consumer segments simultaneously.

Some of Rebel’s most successful brands include Behrouz Biryani, a premium offering with a narrative of royal heritage and authentic flavors, which taps into India’s deep cultural affinity for biryani and has become a $12 million entity within 18 months. Another brand is Oven Story Pizza, which differentiates itself with indulgent, cheese-heavy pizzas designed to cater to Indian tastes, providing an alternative to global players like Domino’s. Finally, Sweet Truth, a dessert brand focused on cakes and pastries, which complements other Rebel brands by targeting post-meal cravings.

When we visited, we had lunch at their HQ, and I had the pleasure of eating the biryani. Had you not told me it was made in a cloud kitchen, I would never have guessed. One student mentioned she was a Behrouz Biryani customer but was unaware until recently that it was made in a cloud kitchen.

A unique challenge for cloud kitchen brands is the notion of authenticity because, unlike traditional restaurants, where customers can see chefs preparing food and feel the ambiance, cloud kitchens lack this physical touchpoint. This makes it harder to establish trust and authenticity—a fact reflected in the head chef’s interesting story: when the firm initially tried to deliver pizzas using the brand name Faasos, consumer feedback was negative. Once it introduced a new brand with an Italian narrative, the feedback shifted 180 degrees, even though the food was made in the same kitchen.

Rebel Foods uses the following strategies to address this challenge:

Compelling Brand Narratives: Each brand is designed with a unique story and identity. For example, Behrouz Biryani’s marketing emphasizes its “royal recipes,” while Oven Story Pizza portrays itself as an artisanal alternative to mainstream chains.

Invisible Kitchens: Rebel ensures that customers never perceive the food as coming from a generic kitchen. Each brand operates with distinct packaging, advertising, and customer interactions, masking the fact that the food is prepared in the same facility as other brands.

Focus on Quality and Consistency: Leveraging technology and extremely process oriented operations, Rebel ensures that meals are consistent across locations and orders. This consistency helps build trust over time.

I’ve discussed Cloud Kitchens before and mentioned that their ability to scale is mostly affected (constrained) by the fact that they don’t interact with the end-consumer or maintain their own brand.

Rebel Foods’ strategy aligns closely with the Stan Shih Smile Curve, which emphasizes capturing value at the end of the value chain—branding on one side, and owning the customer interaction on the other side by maintaining their own ordering app (on top of ordering on other apps), as well as the middle (the cloud kitchen itself). This focus on high-value activities allows Rebel to reinvest in brand building and technological advancements, creating a more scalable growth model.

While Rebel Foods has set a benchmark for cloud kitchens, it also faces significant challenges. The rapid proliferation of brands risks overextension, potentially diluting the quality and focus that underpin its success. Additionally, the competitive landscape for food delivery is becoming more intense, with new entrants and increasing commission demands from delivery platforms.

Mumbai’s Dabbawalas: The Original Masters of Efficiency

Both Zepto and Rebel are VC funded firms disrupting decades old traditions in India.

But no exploration of Indian operations is complete without discussing Mumbai’s Dabbawalas.

The story of the Dabbawalas, a unique food delivery system originating in Mumbai, is one of the most iconic examples of operational excellence in the world.

In fact I told my students in advance that despite all the drones and satellite firms, and Zepto and Rebel, the one organization I’m most excited about is the Dabbawalas.

The system was founded in 1890 by Mahadeo Havaji Bacche, who identified a gap in the market: office workers in Mumbai needed home-cooked meals delivered to their workplaces.

Over the decades, this service evolved into a highly efficient logistics network, managed by a workforce known as Dabbawalas, which translates to “lunchbox carriers.” Today (or more accurately pre-Covid), the Dabbawala system is celebrated for its precision, reliability, and simplicity, delivering over 200,000 lunch boxes daily with an error rate of less than one in 16 million transactions—a Six Sigma level of quality. I’m not convinced by the six-sigma claims (did I mention I’m a skeptic?), but this is what’s written everywhere.

But why don’t people bring their own lunch to work?

Rush hour trains in Mumbai are so crowded, that it’s impossible to add a lunch box.

The Dabbawala system’s operational excellence lies in its process, which is designed around a low-cost, high-efficiency model. It relies heavily on human coordination and simple tools rather than sophisticated technology. Here’s a breakdown:

Coding System: The Dabbawalas use a unique alphanumeric coding system to sort and track lunch boxes. Each lunch box is marked with a series of symbols indicating the origin, destination, and the recipient's office building and floor. This simple system eliminates confusion and ensures accurate delivery without relying on advanced logistics software.

Hub-and-Spoke: The delivery process follows a hub-and-spoke structure. Dabbawalas pick up lunch boxes from homes in the morning and bring them to a local hub, where they are sorted and grouped according to their final destination. They are then transported, usually by train, to a central hub near the final delivery area, and local Dabbawalas distribute the lunch boxes to individual recipients:

Synchronization with Public Transport: The system leverages Mumbai’s extensive local train network to move lunch boxes across the city. Dabbawalas operate on a strict timetable, aligning their activities with train schedules to ensure timely delivery.

Team-Based Operations: The workforce operates in teams, with each team responsible for a specific geographic area. Team members collaborate seamlessly, dividing the various tasks, and this collective approach ensures accountability and efficiency.

Flat Organizational Structure: The Dabbawala system operates as a cooperative, with no formal hierarchy. Every Dabbawala is a shareholder in the organization, earning an equal share of the revenue. This egalitarian structure fosters a sense of ownership and dedication among the workers.

Redundancy in the System: To mitigate disruptions, the system builds in redundancies. For example, if a train is delayed, alternate routes and contingency plans are immediately activated. The Dabbawalas’ deep knowledge of Mumbai’s geography further enables them to adapt to unexpected challenges.

The primary value proposition of the Dabbawala system is its ability to deliver fresh, home-cooked meals to office workers with remarkable accuracy and timeliness. For many Indians, especially in Mumbai, food is deeply personal, and the Dabbawalas bridge the gap between the home and the workplace by ensuring that meals retain their freshness and cultural authenticity. Their services are also highly affordable, making them accessible to a broad demographic.

Moreover, the Dabbawalas’ reliability has earned them the trust of their customers. For over a century, they have maintained an impeccable track record, often delivering meals under challenging conditions such as monsoons, strikes, or public transportation breakdowns.

Adapting to a Changing Landscape

Despite their historic success, the Dabbawalas now face significant challenges as the food delivery ecosystem evolves with the rise of digital platforms and players like Zepto and Rebel Foods. These modern services cater to a tech-savvy, convenience-driven customer base, offering features like app-based ordering, diverse cuisine options, and hyper-fast delivery times.

Several macro trends are putting pressure on the Dabbawalla model:

Dual-income families: Growing household incomes increase demand for convenient food solutions. If in the past, the mother or the wife stayed at home and prepared the food that was picked up by the dabbawalla, more women are part of the workforce and fewer couples live with or near their parents.

Fast delivery expectations: Customers value speed, even at a premium. As the middle class grows in India and increases its earnings, more people are willing to pay for an on-demand service.

Evolving workplace norms: With schools banning food delivery and hybrid work models gaining traction, firms must adapt to shifting consumption patterns.

Cloud kitchens, like Rebel’s, capitalize on these trends with scalable, tech-driven solutions.

One of the key distinctions between the Dabbawalas and these new players lies in the underlying business models. Platforms like Zepto promise deliveries in under 10 minutes by leveraging dense local networks of dark stores and advanced logistics algorithms. Rebel Foods, on the other hand, has revolutionized the food industry with its cloud kitchens, enabling the creation of multiple brands under one roof to maximize operational efficiency and consumer choice.

In contrast, the Dabbawala system operates without digital infrastructure, relying on manual processes and traditional methods. While this has historically been their strength, it also poses a limitation in adapting to changing consumer preferences. Younger consumers may prioritize speed, variety, and the convenience of app-based services over the nostalgia and simplicity of the Dabbawala model.

To remain relevant in this evolving landscape, the Dabbawalas have begun experimenting with digital integration and partnerships. For instance, they have collaborated with app-based platforms to expand their reach and offer additional services. They also started having their own cloud kitchen where their customers can order food and have it delivered to their office by a dabbawalla.

Before Covid the organization delivered 200,000 lunches a day (at a cost of 15 rupees for pick up and delivery, back and forth) and fell to 90,000 lunches post Covid.

These initiatives allow them to cater to a broader audience while preserving their core identity, and are now up to delivering 120,000 lunch boxes per day.

The Dabbawala system represents a timeless example of how simplicity, discipline, and human ingenuity can create a world-class logistics operation. But it shows yet again that organizations must continue and evolve.

Lessons for Managers

India’s food ecosystem exemplifies what I call the “constant reconciliation of market needs and operational capabilities.”

The stories of Zepto, Rebel Foods, and the Dabbawalas illustrate a fascinating journey of food delivery, and offer insights for global firms. While each model operates in a distinct context, they share a common thread: an unrelenting focus on customer needs, operational efficiency, and the pursuit of sustainable business models.

At one end of the spectrum lies the Dabbawala system, a testament to enduring simplicity. For over a century, Dabbawalas have built a reputation for delivering home-cooked meals with an unmatched combination of reliability and affordability. Their model emphasizes trust, cultural authenticity, and a deep connection to their customers’ lifestyles. However, as urban lifestyles shift and consumers increasingly prioritize convenience, this model is being challenged by the tech-driven dynamism of platforms.

Zepto represents the cutting edge of consumer expectations in a digital-first world, appealing to a younger, tech-savvy demographic, while Rebel Foods occupies a middle ground, addressing the need for variety and quality through its cloud kitchen model while leveraging economies of scale to serve diverse customer segments efficiently.

Both Zepto and Rebel Foods cater to a consumer base that values instant gratification and digital engagement—a stark contrast to the Dabbawala model’s emphasis on tradition and simplicity.

The operational models of these three players highlight the evolution of logistics and supply chain strategies.

As the food delivery landscape continues to evolve, it is not a question of whether tradition will be replaced by innovation, but rather how these models will coexist and adapt. The Dabbawalas, with their rich legacy, represent a cultural anchor that appeals to customers valuing authenticity and sustainability.

Final Thoughts

Not all innovations are equally sustainable. The dabbawalas’ consideration of 30-minute deliveries raises concerns as their system is optimized for low-cost, scheduled logistics, not rapid response. Attempting to compete in quick commerce could undermine their operational model.

Similarly, Zepto’s rapid expansion will test its ability to maintain service quality while improving unit economics. The median Indian monthly income of 27,300 rupees ($330) limits how much customers can pay for convenience, underscoring the importance of affordability.

India’s food delivery ecosystem offers a masterclass in aligning operations strategy with market realities. Firms like Zepto, Rebel Foods, and the dabbawalas remind us that operational excellence is as much about cultural alignment and simplicity as it is about technology and speed. As these firms evolve, their successes and challenges will continue to provide interesting lessons for managers worldwide.

But most importantly for me, is that while Zepto has its algorithms, Rebel Foods has its cloud kitchens, and the dabbawalas have a lunch box and a bike—all three prove that the most important ingredient in delivery (and possibly in business in general) isn’t technology; it’s trust.

Such a fascinating read!

Really helpful read, thank you, professor!