A couple of weeks ago, the WSJ published an interesting article on how airlines are slowly changing their policies regarding the handling of checked and non-checked bags:

“Delta announced this week it’s hiking its checked-bag fees for the first time since 2018, joining other major airlines in charging flyers more for luggage, while also cracking down on smaller third carry-on items that boarding agents didn’t use to bat an eye at.”

The central assumption is that charging a fee for checking in bags is nefarious and should be banned.

As you can imagine, I have an opinion on this.

Why Should Anyone Like Baggage Fees?

One thing is clear: people hate baggage fees. They hate them more than flight delays, crying babies, and unruly kids.

Who are you, people?

However, the fact that people hate these charges doesn’t mean they’re not beneficial to society.

Several years ago (2011), I worked on a project with Marty Larivier and Achal Basamboo, colleagues of mine at Kellogg at the time, where we tried to address the question of whether a social planner would charge for luggage. What do I mean by “social planner”? It’s a term we academics use to replace “God.” In other words, someone who could look at all the stakeholders –consumers and airlines– together and induce people to make the best decisions for the overall good. In essence, our question was whether we’re better off with passengers not paying for their bags and, instead, having them bundled as part of their ticket.

Specifically, our paper “Would the Social Planner Let Bags Fly Free?,” explores the economics and strategic implications of unbundling services in the airline industry with a focus on baggage fees (but could also apply to meals or boarding pass printing). We delve into whether services should be sold as an inclusive bundle or priced separately using airlines’ practice of charging for checked bags as a case study. During our discussions, we would refer to this paper as the “Fee to Pee” project —at the time, Ryanair was planning to charge passengers either 1 Euro or 1 British pound to use the toilet for flight durations of one hour or less. The airline claimed that eliminating two of the three bathrooms on the plane could add six extra seats. Ryanair’s brash chief executive, Michael O’Leary, explained the general sentiment:

“Like, paying for checked-in bags: It wasn't about getting revenue. It was about persuading people to change their travel behavior—to travel with carry-on luggage only. But that's enabled us to move to 100% Web check-in. So we now don't need check-in desks. We don't need check-in staff. Passengers love it because they'll never again get stuck in a Ryanair check-in queue. That helps us significantly lower airport and handling costs.”

Our study employs a theoretical model that analyzes a service consisting of a main service and an ancillary service (e.g., transporting a passenger and handling their checked bags). We consider the impact of unbundling these services on customer behavior, firm profits, and overall social welfare under different market conditions (single segment, multiple segments, monopolistic, and competitive markets) and customer characteristics (risk neutrality and risk aversion).

Our main assumption is that people can exert effort to reduce their need for these services. For example, people can pack their bags better or bring fewer pairs of shoes to reduce the need to check in bags. I try to never check in a bag, even if I’m going on a two-week business trip. I use the “two by two by two” system when I travel: two jackets, two pairs of pants, and two pairs of shoes that can create 2^3 different combinations (all paired with my signature blue shirt, of course).

In our paper, we assume that the imposition of ancillary fees can influence consumer behavior. Specifically, paying for services like checked baggage can encourage consumers to alter their behavior (e.g., travel with less luggage) to avoid fees, which can potentially reduce the airlines’ associated costs.

We use the model to derive several interesting insights:

Unbundling Leads to Socially Efficient Outcomes: We show that charging for ancillary services can lead to socially efficient outcomes by incentivizing customers to minimize their use of costly ancillary services, thereby aligning their behavior with cost-saving measures that benefit the firm and society.

Profit Maximization Aligns with Social Efficiency: We show that a profit-maximizing firm (as all firms are) will set ancillary fees that induce the socially optimal level of customer effort to avoid the ancillary service, regardless of customer heterogeneity or competition.

The research highlights how imposing taxes on main services but not on ancillary services can lead to inefficiently high baggage fees and excess consumer effort. Additionally, customer risk aversion can influence the airline’s decisions, potentially leading to bundling services to avoid imposing risk on their customers, who in our case study, don’t know if they’ll have to check in luggage until the last minute.

And while this may not be what you want to hear, the findings suggest that the contemporary practice of unbundling services in the airline industry could be seen as an attempt to achieve greater operational efficiency and social welfare rather than merely a strategy for revenue enhancement.

Specifically, applying these findings to airlines’ current behavior would suggest that airlines are partly motivated by a desire to improve operational efficiency and align customer usage with the true costs of providing ancillary services. The effectiveness of these strategies in achieving socially optimal outcomes, however, may be influenced by factors such as tax policies, customer risk preferences, and the complexity of customer segmentation strategies in practice.

Empirical Validation: Impact on Prices

The paper above is theoretical (which means we built a simplified model to study the main tradeoffs). Hence, a valid question is whether our findings are empirically supported or confirmed. In particular, one of the most important assumptions or observations is that when buying tickets, customers take into account the “full price” of the ticket (the price for the flights plus the price of ancillary services), so airlines charging for bags will have to adjust the price of their main service.

An article written by Lei He, Myongjin Kim, and Qihong Liu (“Competitive Response to Unbundled Services: An Empirical Look at Spirit Airlines”) explores the ramifications of Spirit Airlines’ decision to charge passengers for carry-on baggage, which was announced in April 2010. This study provides empirical insights into how such a policy affected the pricing strategies of Spirit’s competitors across various markets.

The researchers used a difference-in-difference estimation approach, focusing on route-level data to construct a control group that best matches the markets served by Spirit (the treated group). They analyzed the impact of Spirit’s carry-on baggage fee on its rivals’ ticket prices, considering both low-cost and legacy carriers, and subcontracting behaviors.

Their main findings are that after Spirit implemented the carry-on baggage fee, not only did its average fare go down by about 4.4%, but its rivals reduced ticket prices by approximately 5.8%. The study found no significant difference in response between low-cost carriers (LCCs) and legacy carriers. However, carriers that subcontracted operations to regional airlines decreased their prices by more than 10%.

Interestingly, the study didn’t find a significant difference in how low-cost and legacy carriers responded to Spirit’s policy change. This suggests that the competitive pressure exerted by unbundling practices like carry-on fees might have a broad and somewhat uniform impact across different types of airlines.

Empirical Validation: Impact on On-time Departure

The key underlying idea is that airlines charge to educate their customers and improve their overall service. However, it may be questioned whether we see this behavior in the year after we start charging these fees.

The paper “Do Bags Fly Free? An Empirical Analysis of the Operational Implications of Airline Baggage Fees” investigates whether the implementation of checked baggage fees by airlines led to improved operational performance, specifically regarding on-time departure. The study focuses on the period around 2008 when most U.S. airlines began charging fees for checked baggage. The central hypothesis is that charging for checked bags would encourage passengers to travel with fewer bags, thereby improving airline cost efficiency and operational performance. Southwest Airlines, which did not implement such fees and, instead, capitalized on a “Bags Fly Free” marketing campaign, serves as a counterexample within the industry.

The researchers utilized a publicly available database of airline departure performance to assess the impact of baggage fees on airlines’ operational metrics. They employed an event study methodology, analyzing data from May 1, 2007, to May 1, 2009, to compare on-time departure performance before and after the implementation of baggage fees. The analysis considered the impact on airlines that introduced baggage fees and those that did not, across various market segments.

Their main finding is that airlines implementing checked baggage significantly improved departure performance post-implementation. This suggests that the anticipated efficiency gains from reduced baggage handling were somewhat realized.

Interestingly, airlines that did not charge for checked bags (e.g., Southwest) also experienced some improvement in on-time performance, albeit to a lesser degree. This improvement is likely due to overall reductions in baggage volume within the system, benefiting all carriers indirectly.

The most substantial improvements in on-time performance were observed during peak evening departure times, indicating that imposing baggage fees had a more pronounced effect during periods of high operational pressure.

In the context of the “Would the Social Planner Let Bags Fly Free?” paper, this study as well as current airline practices reveal a nuanced picture of unbundling strategies in the airline industry. The findings validate some of the theoretical predictions from the “social planner” paper regarding the efficiency gains from unbundling services like checked baggage.

Can the Paper Explain What we see?

Back to the WSJ article which started all of this.

The article documents a Southwest Airlines flight to Baltimore in which the gate agent announced the exhaustive list of items counting toward the two-item carry-on limit, including fanny packs and blankets. The article describes how Southwest had quietly tightened its carry-on rules on February 22, as detailed in an internal memo. Focusing on the number of carry-ons rather than their size, the policy shift was part of a broader industry trend to optimize cabin space and streamline the boarding process.

Delta employs similar practices, and United has also started to enforce more stringent personal item policies, often requesting passengers to consolidate smaller bags.

The “social planner” paper posits that unbundling services and charging separately for ancillary items can lead to more socially efficient outcomes by encouraging passengers to minimize their use of services that are costly for airlines to provide. This logic underpins Southwest’s decision to enumerate items like cross-body bags and pillows as personal items, a move aligned with the industry’s efforts to reduce the need for overhead bin space and expedite boarding. This move ultimately enhances operational efficiency and passenger experience and benefits society in general.

While initially surprising to passengers, these measures reflect airlines’ strategic responses to the challenges of carry-on management. By delineating specific items as personal carry-ons, airlines aim to encourage passengers to reconsider the necessity of each item, thereby aligning consumer behavior with the airline’s cost-saving and efficiency goals.

It’s important to say that I don’t argue that additional revenues have nothing to do with these charges. Some airlines admit that this is used to increase revenues:

“‘While we don’t like increasing fees, it’s one step we are taking to get our company back to profitability and cover the increased costs of transporting bags,’ JetBlue said in a statement about its latest increases. ‘By adjusting fees for added services that only certain customers use, we can keep base fares low and ensure customer favorites like seatback TVs and high-speed Wi-Fi remain free for everyone.’”

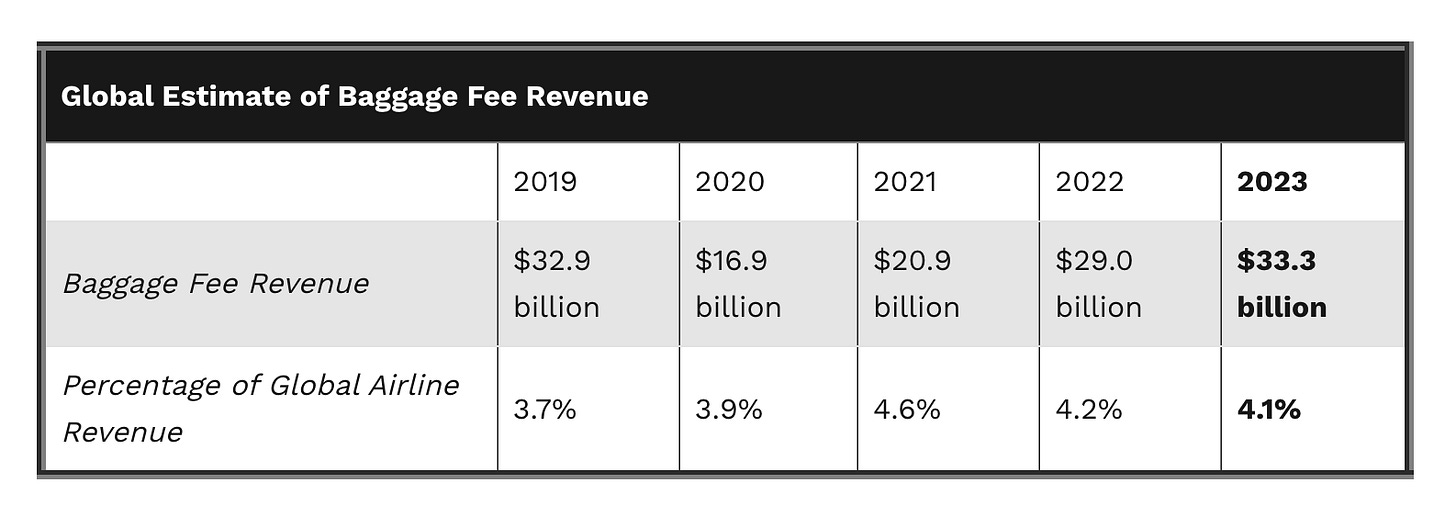

But, it’s important to note that airline baggage fee revenues are only a small fraction.

AA’s bag fees generate a billion dollars in revenues, making it an airline with $52 billion. So, it’s not a massive part, but one has to look at the full picture: the one about “educating customers” and the societal one.

We must also acknowledge that the dynamics of competition within the airline industry have undergone significant changes. The intense rivalry that characterized the sector in the past has given way to a more consolidated landscape, with fewer carriers competing for market share. This makes it easier to increase fees without fearing retaliation from customers.

End Notes

In the big picture of air travel, a few truths are universal, yet curiously, seldom acknowledged:

The Paradox of Baggage Fees: Baggage fees represent a significant aspect of airlines’ revenue management and cost reduction strategies despite being unpopular among consumers. While often criticized, these fees play a pivotal role in airlines’ financial sustainability. This situation is akin to an unspoken acknowledgment of necessary, albeit unwelcome, practices within consumer transactions.

The Misconception of Hidden Fees: As of 2024, the notion that the airline industry uses “hidden fees” is outdated and the idea that fees are concealed from consumers is a misconception. If you want to know how much you’ll pay for additional fees, just Google the information. Nevertheless, the persistence of the term “hidden fees” suggests a disconnect between consumer perception and the reality of straightforward fee structures.

And this brings me to the final point.

The Ambivalence Toward Frugality: Pursuing cost-effective travel options reveals a paradox in consumer behavior. Travelers diligently seek out the most affordable flights, demonstrating a clear preference for value. However, there is a reluctance to openly acknowledge this frugality, especially regarding additional costs such as baggage fees. This ambivalence may mask a deeper discomfort with the trade-offs required to achieve savings, suggesting a complex relationship between value-seeking behavior and perceptions of thriftiness.

So, next time you’re begrudgingly paying those baggage fees, remember: It’s not just about the airlines’ bottom line; it’s a carefully choreographed dance to keep us on our toes. And just like any good workout, you might not like it at the time, but it is (supposedly) for your own good.

this was an awesome read! but one question - why does operational efficiency = social efficiency? given that customers *believe* checked baggage actually *reduces* flight times (even though that is not the case), how does your definition of social efficiency consider the psychological benefits associated with allowing free checked bags?

Fanny packs counting as a personal item?! This is an outrage!