Ration(alizing) the Chip Shortage: Grinding to a Halt

One of the addictions I developed during COVID was to the process of coffee making. I was never really addicted to coffee. I could completely stop if I chose to. I just like drinking it. I then found James Hoffman, and my world has changed. I started discussing blooming phases and agitation, clarity, and astringency. I started using a refractometer to measure extraction yield and optimize my routine. I also realized I need a new grinder. After lengthy research, I ordered the Option-O Lagom P64 In February. And a few weeks ago, this came:

“We have informed all our customers in the March batch via email but thought we should announce it here too for transparency sake. We have all machined parts in house and were ready to go. But unfortunately, we were given a last-minute notice by our PCB supplier that they too have been affected with the recent wafer shortage and are unable to deliver the PCB that we ordered. We are working with the supplier to find a solution/alternative. At the moment, we are estimating there will be a 4-week delay to the March batch due to this reason.”

I know. You are probably saying people can't buy a new car or a computer, and you complain about your coffee grinder. I will take the fifth on this.

On a more serious note, the impact of the semiconductor shortage is quite significant. This week, several automotive manufacturers announced that they would reduce the number of shifts they operate, given the scarce supply of semiconductor chips. This impacts both people who look for a new car and those who work on these lines.

The Reasons: Both Demand and Supply

There are many reasons for this shortage, both related to the demand side of the equation and the supply side.

On the demand side, we have seen an increase in demand for cars due to the pandemic. People are reluctant to use public transportation due to COVID. This and the fact that people had higher disposable income surprised automotive firms, which were expecting the opposite. While most cars are still driven (no pun) by mechanical elements, there are significantly more electric components in a car than in the past. In the automotive industry alone, people expect the shortage of semiconductor supply to drive around $61B of losses, specifically impacting China.

A similar surge in demand occurred for consumer electronics due to the need to work from home, the move to hybrid and online schooling, and the fact that people went to fewer movies and restaurants, enhancing their entertainment options at home.

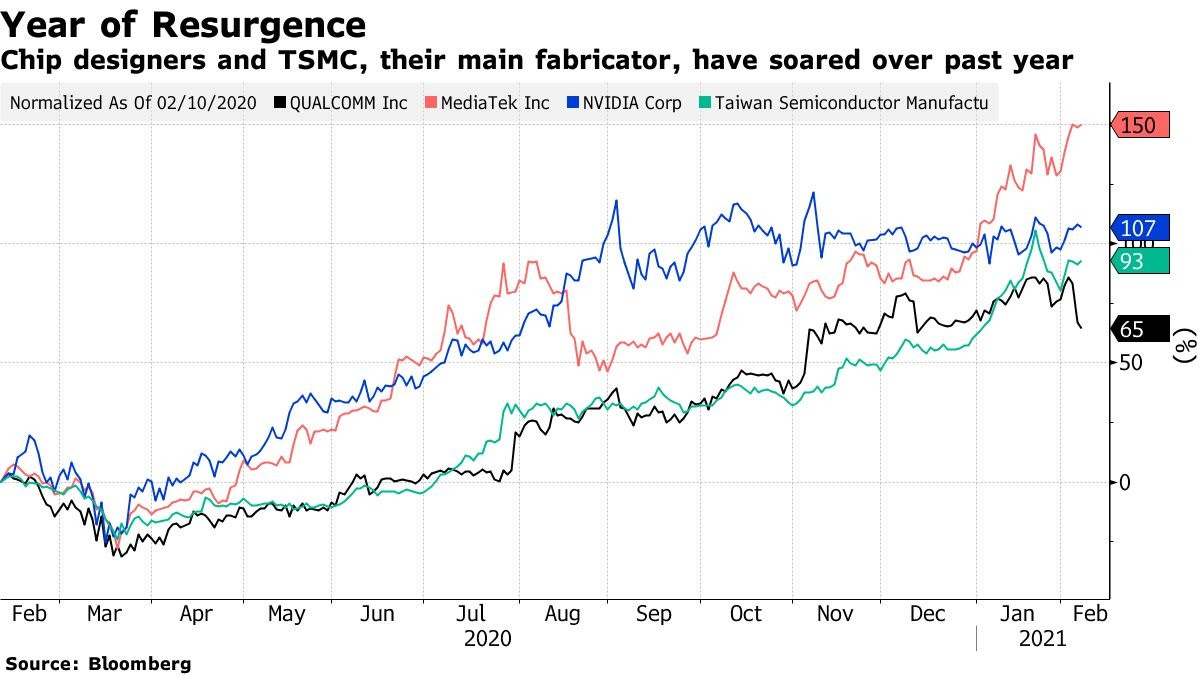

The overall impact is that since March, the demand for semiconductor chips has been only increasing:

As firms were observing this surge, the semiconductor supply chain has been experiencing significant supply shocks.

The trade crises between the US and China resulted in Chinese firms hoarding inventory:

“Industry executives also blame excessive stockpiling, which began over the summer when Huawei Technologies Co. -- a major smartphone and networking gear maker -- began hoarding components to ensure its survival from crippling U.S. sanctions.”

Power outages across Texas caused by the cold front in February shut down several semiconductor chipmakers’ plants, among them NXP and Samsung. Another chip maker, Renesas, located in Japan, had a fire in a plant where two-thirds of its production goes to automotive chips. You add these to the fact that semiconductor firms had limited capacity, to begin with, and it is clear that the problem is quite significant.

Let me add one more reason for this shortage: everyone is exaggerating their orders. They are playing what we would like to call a "rationing game":

“There’s a chip stockpiling arms race,” said Will Bright, co-founder, and chief product officer at Drop, which uses custom chips in headphones and keyboards.”

In fact, I will argue that because of this behavior, not only are WE making it worse. We WILL make it much worse in the future.

Rationing Game

The key idea behind rationing games is that in times of insufficient capacity but ample demand, firms realize that they compete on supply. Suppliers like to maintain good relationships with the OEMs and thus ration their supplies. You can prioritize bigger customers. You can prioritize strategic customers. But the reality is that everyone has incentives to inflate the magnitude and urgency of their order to ensure their share of the capacity, potentially even increasing their share, and thus stealing market share from the competition.

The immediate impact of this is an inflation of the orders made by firms.

And this brings me to the long-term implication of this behavior. Estimating demand is complex. Primarily as new technologies emerge, it's hard to estimate the new demand. When you build capacity, you need to project many years forward. Building capacity and inventory are like placing a bet at the Kentucky Derby.

As Yogi Berra said, "predictions are hard, especially about the future.” Estimating demand is complex because you try to estimate other people’s behavior, who themselves are trying to estimate the demand of other people. So if you are deep in the supply chain, where Intel and TSMC, and chip manufacturers are, you need to estimate the demand of Volkswagen, which is trying to estimate the demand of both its end-consumers.

From an OEM point of view, the question is whether this demand increase is real and indicates future trends. If it's real: you want to capitalize on it and overbuild capacity. If it's not: overbuilding is going to be a very costly mistake. You, your shareholder, and employees are going to bear the cost. The point is that you genuinely don't know what's the new reality or just OEM’s temporarily inflating their orders to gain a share of your capacity.

Don't get me wrong: the disruptions are real, and the changes in demand are fundamental: cars need more chips. But do people really buy more consumer electronics? What part of that is driven by the pandemics where all of us work from home and need more cameras and laptops and games and, yes ... coffee grinders. And what part of it is due to the rationing.

Rationing is not an entirely new phenomenon: products from American cars to luxury watches have experienced similar stress. As my former colleague Robert Bray shows, these rationing games may cause the bullwhip effect: minor disruptions downstream in the supply chain are amplified further upstream.

The Future

The solution: visibility into the supply chain. If you can see the actual demand up and down the supply chain, you can make better decisions. We are still going to have shortages. But the recovery is going to be faster, and the after-shock is going to be minimized.

From a game-theoretic point of view, I can say that this is not going to happen. As I discussed before, firms are strategically reluctant to share information.

What else can suppliers do? Make it hard for firms to cancel their orders:

“Suppliers are wary that the surge in demand may not last, with panicked buyers increasing order volumes or placing orders with multiple companies. San Jose, Calif.-based Broadcom Inc., one of the world’s leading chip companies, is trying to ensure orders coming in reflect actual demand. It recently reminded investors that it doesn’t allow customers to cancel chip orders to deter some buyers from making purchase commitments out of fear of shortages.”

So what will happen? Expect a rocky few years, and let's all hope that this is a new reality and that the upcoming infrastructure bill will help alleviate some of the future issues.