The End of Just-In-Time is Near. Are you ready for what comes next?

During the last few weeks, several articles were published stating that Toyota and other carmakers will be retreating from Just-in-Time (a production method which minimizes inventory levels across the supply chain). This week, we also heard that governments around the world will be intervening in the supply chains of the automobile industry. The combination of the two is not a coincidence. Furthermore, I believe these developments signal important changes to other industries, regardless of whether they seem to be related to the car industry or not.

Let me start with the simple facts. Over the last few weeks, several articles were published documenting the retreat from Just-in-Time.

“The just-in-time model is designed for supply-chain efficiencies and economies of scale,” said Ashwani Gupta, Nissan Motor Co.’s chief operating officer. “The repercussions of an unprecedented crisis like Covid highlight the fragility of our supply-chain model...Executives say they don’t want to replace just in time entirely because the savings are too great. But they are moving to undo it to some degree, focusing on areas of greatest vulnerability. They are seeking to stockpile more critical parts, especially if they are light and relatively inexpensive yet irreplaceable like semiconductors.”

This may seem like a very specific change in a very specific industry, so it seems fair to ask why I claim that this will have much broader implications. In many ways, I would argue that the automotive industry has been the canary in the coal mine, or maybe the leader and tone-setter for almost all other sectors.

This is a very loaded statement, so let me explain.

The Automotive Industry and Just-In-Time

In order to understand why I attribute so much value to the decision of automotive firms to stop using Just-In-Time, it is important to understand the role the industry has played over the last two centuries in the way we think about production and business.

The automotive industry has been central to the Industrial Revolution. The automobile was the most significant invention of the Second Industrial Revolution and has played a crucial role in shaping the world as we know it.

The automotive industry was also where the assembly line was invented. Many consider the assembly line as one of the most important inventions of the 20th century. The notion that a new, often expensive technology could become affordable by streamlining its production and “stripping” it from its initial high cost was an essential advancement for everything that has followed since.

The automotive industry was also where the Just-In-Time method was “invented”. The Just-In-Time (JIT) concept was part of the Lean Revolution which started in Japan by the Toyota Production System. Some may argue that the origins were in the US, and they will not be wrong. Still, the first, actual implementation of JIT was on the Toyota Production System, as envisioned by Taichi Ohno. The assembly line was still key, but JIT was a sea change because cost was no longer the primary focus, instead, speed and variety were. It’s not that lowering costs were no longer essential, but reducing the cost was just not enough. Wealthier customers in wealthier nations wanted something else: better quality, more variety, faster time to market. And indeed, the JIT concept was built precisely for that.

All other industries followed. From consumer electronics to food and beverage, to even software developments (through ideas like Agile and the Lean Startup), all used different incarnations of the notion of Just-in-Time. Lean and Just-In-Time became the predominant paradigm for business operations.

But now we see the automotive industry deserting it. We also see everyone (and by everyone, I mean the New York Times) blaming JIT for the various shortages around us:

“But the breadth and persistence of the shortages reveal the extent to which the Just In Time idea has come to dominate commercial life. This helps explain why Nike and other apparel brands struggle to stock retail outlets with their wares. It’s one of the reasons construction companies are having trouble purchasing paints and sealants. It was a principal contributor to the tragic shortages of personal protective equipment early in the pandemic, which left frontline medical workers without adequate gear.”

It’s not (Just) Just-In-Time.

While I have argued that one cannot blame Just-In-Time only, it's clear that when firms optimized for it and all KPI's pointed towards limiting inventory, it created the level of unpreparedness we see in many firms and the shortages we see in the market.

But this is not the first crisis. In 2008, the financial crisis required the US government to bail out the automotive firms and we have also witnessed shortages in various markets following the floods in Thailand and the earthquake in Japan. So, it's important to examine what is causing the automotive firms to rethink the concept of Just-In-Time now. Primarily, it seems to be the semiconductor chip manufacturing industry combined with the increased importance of batteries.

This brings me back to the thesis I have outlined: The fact that the automotive industry is starting to desert Just-In-Time signals the end of an era. And the auto manufacturers are not doing this out of choice. They are doing it out of necessity, demonstrating the loss of their centricity to the value chain and the economy.

Let me unpack what I wrote above. Let me start by explaining exactly what Just-In-Time is. The idea behind Just-In-Time (JIT) is to reduce “waste” in the system by synchronizing demand and supply flows. In particular, items only move through the system when downstream nodes need them. JIT does not mean carrying zero inventory but carrying less inventory. If customers change their preferences, the system is much more responsive, given the limited stock, it carries.

However, the implementation of Just-In-Time on top of an assembly line is not only a manufacturing play but rather a power play. All other players in the industry have to organize themselves according to the pace and speed of the automotive firm. They need to make sure that the components are ready when the automotive firm needs them. Quite literally, Just In Time. Suppliers usually co-locate and change their structure to be in a position to execute what is required.

Once Tier 1 suppliers align themselves with this method, they, in turn, require their suppliers (Tier 2 or 3) to follow suit. If executed well, this leads to a very lean supply chain, with little inventory but fully synchronized with consumers’ demand.

It’s not (just) Covid.

All of this works well until the “music stops” and the supply chain is disrupted. And I know many of you think of Covid as the main disruptor, but I claim that Covid only exposed a much more serious issue running long and deep in this industry and the many industries around it.

The main disruptive factor that has been brewing over the last few years is the increased importance of electronics in our life. While you may argue that this is not new, given the role computers and mobile devices play in our everyday life, the extent of the shift and the impact of this revolution on other aspects of our life, is only at its beginning.

Let’s take a closer look at what I am saying. While most of us own a laptop and a mobile device or two, and a gaming console, and a drone, and a coffee grinder (ok, I will stop here) that run on semiconductor chips, the cars we own, to a large extent, are still driven (no pun) by mechanical engines, rather than chips.

The automotive industry has been lagging for a while in integrating smarter and eclectic components. For example, most automotive firms use older generation chips.

Combining the observations stated above, we can conclude that when semiconductor chip OEMs started to run into shortages due to the different disruptions their industry endured, supplying the automotive firms was just not their top priority. As you can see in the figure:

Older generation chips are not all that attractive to manufacture under limited capacity, and automotive firms never really allocated significant attention to this given that chips are still a small part of the cost and value of the car.

But things are changing. Cars are becoming more digitally-driven and differentiated. According to estimates, by 2030, 45% of the cost of the vehicle is going to be driven by computing components. In my opinion, this is an underestimate, the same way that the 40% stated in this article is an overestimate.

Whether this is merely a cost shift or will have much broader implications remains to be seen, but I will argue for the latter.

The Car of the Future

One of the most valuable models to refer to when thinking about changes of this type is Clay Christensen’s “Law of conservation of attractive profits”:

"When attractive profits disappear at one stage in the value chain because a product becomes modular and commoditized, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage. That is, the location in the value chain where attractive profits can be earned shifts in a predictable way over time."

And this is what we are going to see in the automotive industry. Until now, when it comes to cars, the point of differentiation is the assembly line. Most cars have similar chassis and similar drives with some minor changes in design. Car enthusiasts will disagree with me, but most cars are not all that different in terms of their core performance. The car has become a fairly modular product.

The Law of Attractive Profits says that when some parts of the value chain become modular (and thus commoditized) other parts start to integrate, primarily around areas where the current value chain fails to deliver the required results and experience.

I can talk about my experience as a consumer. I don’t enjoy driving. I don’t care much about the “driving experience” as long as I can get from point A to point B. Most cars do that pretty reliably at this point. However, I do value an efficient navigator or entertainment system. Unfortunately, I use my mobile device to supplement these areas, where the car does not do such a good job. Over the last 5 years, I have owned a BMW and an Audi, both have very “fancy” navigation systems but fail to do what Waze does well; navigate efficiently when there is congestion. Both cars have great sound systems, but neither can integrate with my podcast list without the use of my phone. I use the car to move as fast as possible (speed-limit and safety bound) while learning about Ovid and the Second Barons’ war. Both of these functions (navigation and entertainment) fail to be delivered, and I am not even talking about self-driving capabilities which, at best, are limited in most cars.

What will the solution be? If we want to make predictions, we can look at adjacent industries. In the PC era, Intel designed and manufactured its chips and then had the PC manufacturers build their computers to their speed and performance. When the mobile era came, the power shifted and required the chip designer to collaborate and integrate with the phone brands. Intel, who was slow to adjust, was left behind.

We should expect a similar change in the automotive industry. As cars are going to be further differentiated by computing capabilities, these will have to be integrated into the design of the car, rather than purchased as an outside component.

And this is exactly where the idea of Just-In-Time breaks:

“Customers need to change,” said Hassane El-Khoury, chief executive officer of ON Semiconductor Corp., which gets more than a third of its revenue from the automotive market. “That just-in-time mindset doesn’t work...Automakers can no longer “assume the dominance of an 800-pound gorilla” in negotiations with chip companies and battery makers, said Mark Wakefield, head of the auto practice at consultancy AlixParters...Semiconductor makers are demanding guaranteed, long-term orders rather than the short-term flexibility the carmakers are used to. The chipmakers’ assertiveness, even under pressure from lawmakers, underscores the rebalancing of power from the companies whose logos are on the cars to those that provide the advanced technology that runs them.”

The Automotive Industry and its (soft) Power

You may argue the trend I describe above is not new, and indeed the changes in the distribution of value-added in this chain have been hinting towards this for a while:

“Worldwide, average margins have fallen from 20% in the 1920s to 5% now, with many companies losing money. This poor profitability performance is reflected in the industry's market capitalization: despite its huge revenues and employment, the automotive industry accounts for only 1.6% of the stock market in Europe, and 0.6% in the U.S. There is a big contrast between the industry's lackluster financial success and its oversized social role, share of employment and political influence.”

Note that I am not claiming that cars will stop being assembled, but rather that the assembly line will lose its power to dictate how all other players conduct business. With it the JIT and the automotive industry will lose their key positions in the western economy. In terms of GDP and employment, the automotive has been an extremely important industry:

“The auto industry is one of the most important industries in the United States. It historically has contributed 3 – 3.5 percent to the overall Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The industry directly employs over 1.7 million people engaged in designing, engineering, manufacturing, and supplying parts and components to assemble, sell and service new motor vehicles. In addition, the industry is a huge consumer of goods and services from many other sectors, including raw materials, construction, machinery, legal, computers and semiconductors, financial, advertising, and healthcare. The auto industry spends $16 to $18 billion every year on research and product development – 99 percent of which is funded by the industry itself. Due to the industry’s consumption of products from many other manufacturing sectors, it is a major driver of the 11.5% manufacturing contribution to GDP.”

This is exactly why the government is intervening. And I am not only talking about the Biden-Harris Administration Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force. The EU is getting involved as well:

“If a big bloc like the EU is not in a position to produce microchips, I don’t feel comfortable about that,” Merkel said during a virtual speech last month to a conference hosted by German research organizations. “If you are a car nation, it is not really good if you cannot produce the main component.”

If automotive firms want to remain central to the next generation of industry, it is essential that they rethink the way that cars are manufactured. The best window into this is Tesla. Still assembled, but the main brain of the car maintains the ability to add features over time. It has a tight integration between the electronic and the mechanical elements.

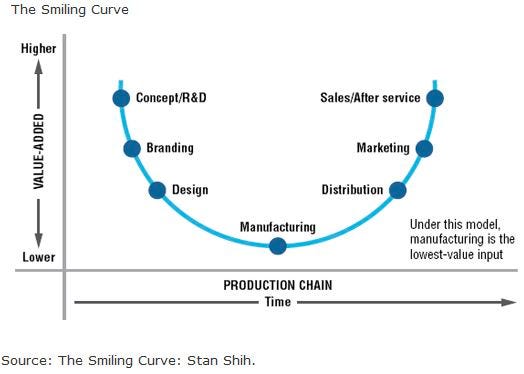

What happens to car markers is very much along the lines of the Stan Shih Smiling curve (see below). They are merely the assemblers of the cars, at the bottom of the value chain. They still control distribution, but with Tesla’s distribution model and Amazon owning Zoox, you may soon order your car over your iPhone. You may not even own this car. But this is a different discussion.

The impact on the automotive industry should be clear. This is the end of an era and the shift away from JIT is a necessity in a world where the power of differentiation is not held by these firms anymore.

The main point of this post, however, is to say that in almost any industry, the JIT method was copied as the predominant way of running operations and product development. We should expect a new paradigm to emerge in the next few years. One that will most likely not be influenced by the automotive industry. Predicting which one, however, will be a much harder job.