The Scaling Illusion: Easier to Launch. Harder to (Hyper) Scale

A week ago Clubhouse, the voice-first social network platform, launched its much-anticipated Android version, after being, for quite some time, available only to iPhone users:

“Live audio app Clubhouse will begin introducing a test version of its app to Google’s Android users in the United States on Sunday, the company said, in a potentially big expansion of its market.”

The app has been quite an interesting phenomenon, both in terms of being an invite-only app, and the type of personalities it managed to attract (Musk, Gates, and Andreesen to name a few). The firm also attracted attention through the funding levels it garnered while using no monetization scheme, or even a hint of one, but with significant user engagement.

However, after being an initial success, the number of downloads and the amount of overall engagement started to falter. Various explanations arose for this.

First, many of the existing social networks realized that voice is the new text and started building this functionality into their existing apps: Twitter built Spaces, FB is building Hotline, and even LinkedIn is considering it. I am not saying that they will all be successful, but they will clearly make a dent.

The second explanation is that Clubhouse was the perfect product during Covid and social distancing. At a time when meeting in person was strongly discouraged, the ability to have or to listen to a conversation was exactly the type of social connection many were craving.

The third explanation is that people realized that it's a zero-sum game: one cannot be on Clubhouse, and Twitter, and FB, and Snap, and be productive at the same time. People started making decisions regarding a preferred app to spend their time on. The common assumption behind Clubhouse was that, while you cannot be on Facebook and be productive at the same time, you can do so while being on a voice-only network (the same way we listen to music while we work). The realization that this is not the case, meant that the market was actually smaller than initially assumed, and is, in fact, shared with and split among other content providers and social networks.

The idea behind launching the Android version was to try to demonstrate that there is another reason for this downward trend: the fact that the app was only limited to the iOS ecosystem. In many countries, such as India, this is a huge limiting factor. However, when looking at the initial numbers post-launch, even though agreeable, they are not as groundbreaking as one might have expected, given the anticipation.

While these are all plausible explanations regarding the struggles of the app and the startup behind it, and although I have written about the firm before, this is not the main focus here.

The main goal of this post is not to diagnose the issues around Clubhouse but to illustrate a phenomenon that is broader. Even within the reality of voice- and video-based networks, we have seen Meerkat using similar tactics by utilizing Twitter as its launch pad, only to be shot down a few weeks later. We have seen a similar story with Houseparty, or Zynga and its FarmVille; an overnight success, which ultimately was limited in its long-term success. You may argue that none of these were really all that great, to begin with, that they just used very successful tactics to lure an initial set of customers, and were then copied by others. But this is part of the story here, so let’s dig a little further.

As we delve deeper and try to understand the mechanism behind the success, we can see a common theme: All of the examples above are firms that were built on the most powerful distribution systems. Clubhouse used the iPhone and its contact list to allow people to invite their friends. Meerkat used Twitter as a way to reach its users and was built on top of the Twitter social graph. FarmVille was built and distributed through Facebook.

This brings me to the main thesis: We are in an era, in which it's easier than ever to launch. It's even easier than ever to scale. But it's harder than ever to hyper-scale. The main reasons that make it easier to launch and get initial scale, are the reasons for the demise of these firms.

While all previous examples refer to social networks and content providers, it is important to note that the same holds for physical products. A year ago, the NY Times wrote about a similar idea, talking about Direct To Consumer brands (DTC for short):

“This development hasn’t gone unnoticed by Neil Blumenthal, another founder of Warby Parker. “It’s never been cheaper to start a business, although I think it’s never been harder to scale a business,” he says. Warby Parker is the most prominent new eyewear brand, but its market share is still less than 5 percent. And in the years since it sold its first pair of eyeglasses, in 2010, other start-ups have launched well over a dozen new online eyeglass brands”

Before demonstrating how and why it is indeed harder to hyper-scale, I think it’s important to first discuss why it's easier to launch and scale.

Easier to Launch

There are many reasons why it’s easier than ever to launch a new product, and although not all are technological, technology clearly plays an important role. The two main technological innovations that enable faster product launches are mobile computing and cloud computing.

When trying to understand the impact of mobility, and specifically the introduction of the iPhone, it is clear that technology in this case is merely the enabler. What mobile computing did was create the most efficient distribution system in history. Throughout history, those who controlled distribution also had disproportionate power. From the Roman Empire to the British Empire, to Walmart, these structures used their control on their distribution networks to create either political or economic value or both.

What the iPhone and App Store, and then Google Play and Android have created are two very efficient distribution systems. At nearly zero cost (and zero marginal cost), almost every person on earth can have the product (or app in this case) with one click. The fact that almost every person has a mobile device, paired with the ability to launch standard products that need little customization to reach customers, is unparalleled to anything in history.

The second biggest innovations were the cloud and internet connectivity. Over the last decade, the speed of the internet has increased every year, while the cost of computing and storage has decreased. If in the past, you needed to invest in servers before even starting anything, in this day and age, you don't even need to own physical and computing resources to build something.

Let’s take a look at the steps needed to launch a product today:

Develop: Software engineering methods have changed and Agile methods have brought significant improvements in cost and time when compared to traditional methods (such as the waterfall model). Using APIs such as Twillio, and no-code environments such as Webflow, you don’t need to spend a lot on development.

Host: The cost of hosting an application is negligible if you use Heroku, AWS, or Azure. In fact, all of these firms offer very favorable terms to startups to lure them to develop on their cloud platforms.

Acquire: As mentioned, the ability to reach new customers is easier than ever (at least theoretically). It took Pokémon Go only a few days to reach 10 million users but took Facebook 2.3 years to reach 10 million users. It also took Pokémon Go only 3 days to lose 10 million users (an achievement in its own right).

Monetize: And then it's also easy to monetize, using platforms like Plaid and Stripe, you can easily monetize the product you built.

In other words, from idea to 10M users can be extremely easy and fast.

If you think this is a feature only of the digital world, then it's enough to look at the reality of physical products. It's easier than ever to manufacture products using platforms such as Alibaba, which makes it easy to find suppliers. You can build a simple online store using Shopify. Most customer acquisition will be done via Google and Facebook. Monetization will be done via Stripe. Warehousing of the products will be done via Flowspace or Bond, and the delivery itself via FedEx or UPS. Of course, most of this can already be done via Amazon, so some people refer to the above supply chain as the Anti-Amazon Alliance.

Easier to Reach Initial Scale

Until now, we focused on the ease of launching a new product, virtual or physical. I would argue that it’s also easier to grow the business and achieve an “initial scale”. Indeed, there is much more noise, since everyone has the same capabilities, but those who do manage to break through see a much faster growth nowadays.

There are many reasons for this, and they are, of course, tied to each other. The first reason is the distribution channels we mentioned above. Whether it’s Amazon, Google, Apple, FB, WeChat, or Twitter, they are all very efficient systems that scale very well. And scaling is first and foremost about distribution.

But distribution means that you also need to be able to scale your resources to provide the product to more people, which leads us to the second reason that makes it easier to scale. Most of the resources needed to deliver the product are “scalable” which means they can grow as you grow. You can add offices as needed via WeWork. You can add cloud services as needed without committing long-term. Most of the APIs that power the systems behind these firms are scalable and require little upfront investment.

Nevertheless, distribution is expensive (FB and Google are not free to the businesses that use them), and building systems requires paying the cloud providers, the API providers, and the people you need to scale. This brings me to the third reason: there are both more funding mechanisms and more money involved in the early growth stages.

Some mechanisms may be driven by current trends. As interest rates remain low (for more than a decade now), those interested in diversifying beyond the stock market choose to invest in private firms. Pension funds, family offices, and endowments have started funneling more money to private equity firms and venture capital funds.

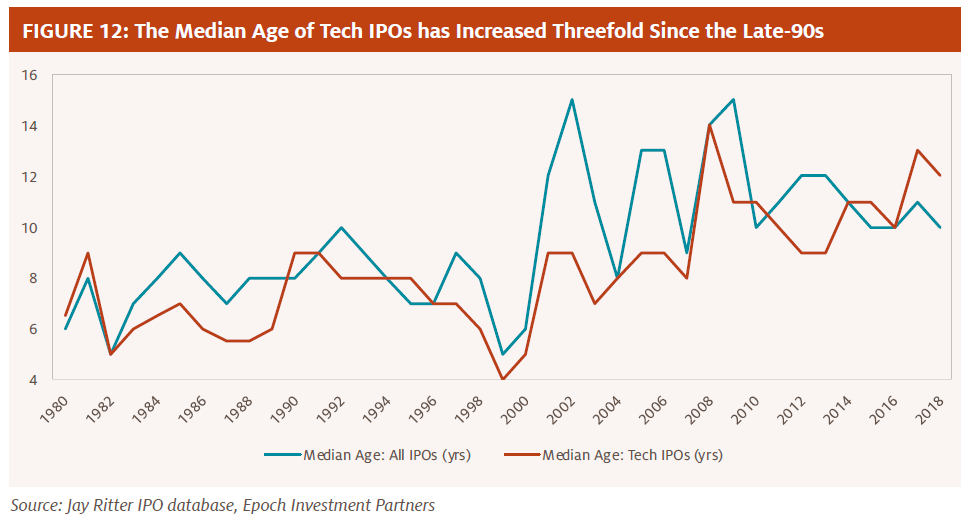

If in the past firms had to become public to be able to tap into additional resources, this is no longer the case. When Facebook went public it didn’t need any funds to grow, and neither did Slack. If you think these are just anecdotes, look at the analysis carried out by Epoch Investment:

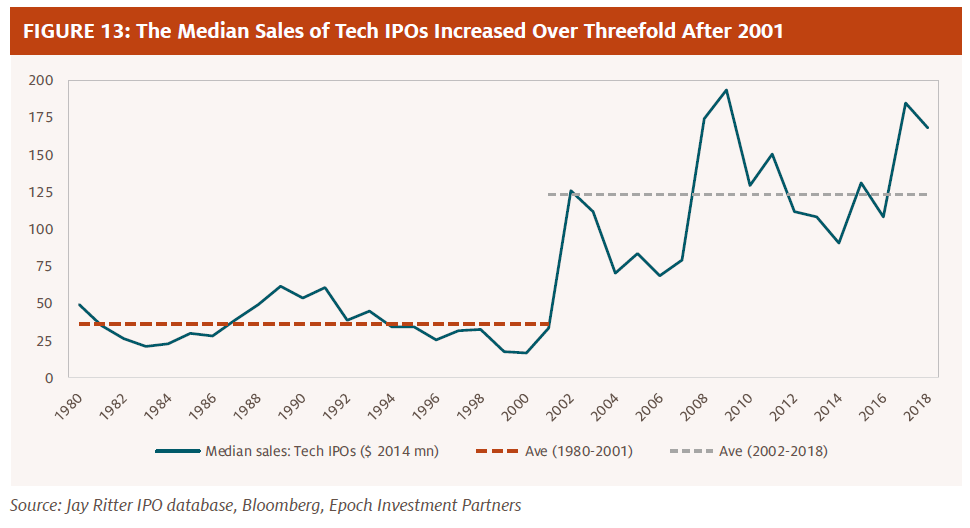

“First, since the dot-com boom the median age of tech IPOs has risen from 4 to 12 years and the median sales of tech IPOs has increased more than threefold. One could interpret these developments as evidence that it is becoming even more difficult to become free-cash-flow generative. However, in most cases, these are real companies that have developed robust, viable and innovative business models and are exhibiting truly impressive sales growth.”

The next graph illustrates that not only did firms become public at a later period of time, but when they did, they were also significantly larger in terms of sales (even if one accounts for inflation, which was essentially nonexistent during these years):

This means that many of the companies entering public markets are fairly well-capitalized and have already proven their business strategy to be viable and robust.

Why is this important? There are two things that come with it: First, it's easier to get resources quickly rather than to go through the lengthy process of an IPO (or even SPAC). Second, and more importantly, it's easier to incubate your ideas for longer under private ownership. VC funds allow you to stay unprofitable longer and focus on growth and product development rather than just pure short-term profitability. While the ability to delay profitability was always valuable, it became even more so the case when more and more businesses rely on network effects, which only materialize at a large scale. If these firms prioritize profitability over growth too early, it will curtail their ability to maximize the potential of their model.

Harder to (Hyper) Scale

Now that we have established the reasons why it is easier to launch and scale a business, the question that remains is, why is it so hard to hyper-scale?

We tend to think about 0 to 1 vs. 1 to N. The launch stage vs the scaling stage. I claim that there is another level, N to N^2, or even better: Exponent of N.

It is already hard to be great, but I claim that, given the ease of launching and initially scaling a business, it is actually much harder to hyper-scale a firm.

If we look at Clubhouse, it is possible that it just needs more time. So, the jury is still out on whether it may be the next TikTok, or Snap (which also needed more time around a fairly lackluster IPO), or Facebook, or Google.

But my argument involves the multiple reasons and technologies I have discussed earlier, which make it easy to launch and scale. In other words, because it's so easy to launch and scale, it's actually pretty hard to hyper-scale.

The first and simplest point is that there are just so many other firms that achieved that level of initial scale, that now, it is just harder to break through. We see it in the note-taking world. For many years, Evernote was the main player. In the last 2 years, we have witnessed an explosion of well-funded firms, all vying to push the envelope, from Notion and Roam, to Obsidian and others.

Since these firms have a limited ability to differentiate and believe it’s a winner-take-all market, they are all burning cash trying to get the next customer. We have seen it with Uber and Lyft. With so much capital out there and so many ways to reach the customer, firms burn cash on attracting customers with limited improvements to the product itself. And the same way it was easy for you to scale, it’s easy for other firms to scale as well, which means that attention is continuously split.

But one may argue that this issue always existed. Firms always copied the best player, and unless that player was able to differentiate and grow fast, other firms caught up.

This brings me to what has changed, and probably my main thesis for this post, which revolves around the firms that make it very easy to scale. These firms have two important activities as part of their business model. They are the main distribution system, while also monetizing the engagement they create. This is true for Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, as well as Apple. They are both the platform and distribution channel. However, we, as consumers, do not engage because they are the distribution channel. We engage in order to meet people (Facebook) or search (Google and Amazon). These platforms are also used by other stakeholders as a way to reach us. Either our attention (Facebook), our intent (Google) or physically, in our homes (Amazon) or phones (Apple).

What does this mean? It means that while these “hubs” provide a very easy way to launch a business as well as access to their customers and users, the moment a firm becomes big enough and interesting enough, as a final user destination, it starts to threaten their main platform business model; their core interaction. The distribution is the monetization mechanism, while the core interaction requires customers to stay on their platform. This is the first rule of platforms: You create engagement between producer and consumers, and the only way to grow is to increase the quantity and quality of these engagements.

Google does not want you to go to Yelp, since the choices you make on Yelp do not translate to better choices for Google. Twitter does not want you to go to Meerkat and Amazon does not want to become an ad agency for brands. The moment a leak is identified in this engagement, these “distribution centers” start losing their ability to monetize through distribution. When small start-ups become a final destination, users lose motivation to remain engaged with the platforms themselves. One might go directly to Yelp, Meerkat, Clubhouse, or the brands’ direct websites. The platforms then lose their appeal as “distribution centers.”

What do these platforms do? Some of the efforts to thwart these startups are going to be legal (either through M&A or launching a competitive internal effort, or launching white labels to compete with brands). Some are going to be questionable, such as demoting on the page rank. Some are going to be outright uncompetitive. And indeed Yelp was suing Google, as just one example.

This is not only about social networks. Amazon, which is the biggest marketplace, is also a retailer in its own right. A WSJ article from last year documented this exact tension.

“We knew we shouldn’t,” said one former employee who accessed the data and described a pattern of using it to launch and benefit Amazon products. “But at the same time, we are making Amazon branded products, and we want them to sell.”

And indeed Amazon is facing a lawsuit in DC:

“The lawsuit, filed in D.C. Superior Court, alleges Amazon illegally maintained monopoly power by using contract provisions to prevent third-party sellers on its platform from offering their products for lower prices on other platforms. The attorney general’s office claimed the contracts create “an artificially high price floor across the online retail marketplace,” according to a press release. The AG claimed these agreements ultimately harm both consumers and third-party sellers by reducing competition, innovation and choice.”

What’s new?

To understand why this is new, we need to understand the type of economies of scale enjoyed by platforms. Traditional post-industrial-revolution era firms and distribution networks enjoyed what we call supply-side economies of scale. The more volume they processed, the lower the cost. These firms wanted to attract more sellers since it allowed them to reduce their own cost of distribution, thus becoming even more competitive. This was their main business model. A cost-driven business model.

The new distribution networks, the Amazons, Facebooks, and Googles of the world are network-mediated platforms that enjoy network effects. Networks are referred to as demand-side economies of scale, because these firms monetize interactions, and the number of interactions as well as the value they create, increase along with the number of platform users. As we add more sellers, the value to consumers goes up (lower prices, more options). As we add more customers, the value to the sellers goes up. For Facebook, the same applies for users (consumers) and advertisers (sellers).

Both types of firms, those that enjoy supply-side economies of scale and those that strive on demand-side economies of scale want the same thing: higher volumes. However, there are two key differences.

The first is that supply-side economies of scale have a diminishing return to scale. Once you reach a certain volume, the marginal benefit is limited. You can only reduce cost by that much. For demand-side economies of scale, this is not the case. You can always add more services, more users, and further monetize them.

The second, and more significant difference, is that for firms using demand-side economies of scale, in order to monetize the interaction, the entire interaction has to happen on the platform. Once there is leakage of information or funds, it becomes harder to monetize and improve the next interaction. Since these firms are not engaged in creating something other than merely facilitating the interaction, once they lose feedback on the quality of the interaction, the flywheel breaks.

In other words, once a service or product becomes too competitive in garnering the attention of users, and can become a destination of its own, it threatens the core business of these platforms (i.e., for FB its social network, for Google, its search engine), and thus, their ability to reach customers, and monetize.

But since the incumbent owns the distribution, it can "choke" the competition easier than in the past. Again: sometimes legally, sometimes less so.

Since these firms have information on the competition and its customers, they are well-positioned to do that. The reality is that the firms I mentioned: Google, FB, Amazon, Apple, and Twitter are relatively well-run firms with a strong emphasis on entrepreneurial culture and execution. If Facebook decides to launch and copy another firm, they can.

Other probable reasons that it’s harder to hyper-scale may include human resources, for example. We still lack enough people to develop all the ideas. Clubhouse could go quite far with only one iOS developer, but that limits their ability to hyper-scale. This, surprisingly, is one area where we have not seen a lot of innovation. New organizational structures that allow firms to manage scale better, but this is a whole different discussion.

In summary, we have seen many firms achieve hyper-scale, and we do see more innovative firms that create these. But the main goal of this post is to say that, while it's much easier to launch and gain scale unless we see significant antitrust efforts, we might not see new emerging hyper-scale firms in the near future.

And it is exactly the mechanisms that enable the ability to launch that also make it hard to (hyper) scale, resulting in the scaling illusion.

Do you see similar dynamics in B2B categories, eg business applications, where the platforms, eg aws, do not compete?